.

.

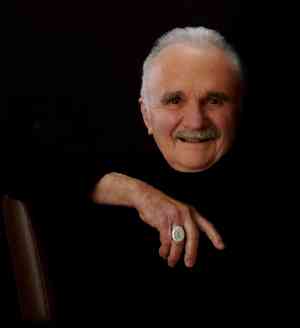

…..In July of 2002, I had the privilege of interviewing the photographer Lee Tanner, whose remarkable images of jazz greats like John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk appeared in the pages of .Downbeat, Rolling Stone and others, as well as on many record album covers.

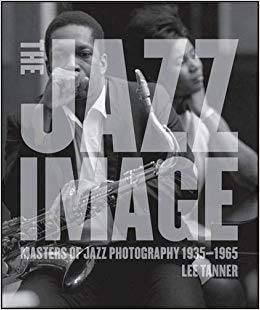

…..Until his passing in 2013, in addition to managing his own photography, Tanner was an important contributor to promoting the legacy of essential jazz photography, having edited the 2006 book .The Jazz Image: Masters of Jazz Photography, 1935 – 1965, an inspiring collection of classic jazz photographs spanning six decades, including works by Herman Leonard, Milt Hinton, Bob Willoughby, Chuck Stewart, and William Claxton.

…..Subsequent to this interview, I got to know Tanner as a friendly acquaintance and personal mentor who was an early advocate of Jerry Jazz Musician. His voice of encouragement (and infectious laughter) remains fresh in my head.

…..The interview (and its introduction) is published here as it originally appeared in 2002. At the interview’s conclusion is an extensive gallery of Tanner’s jazz photography, published with the kind consent of his daughter Lisa, who manages her father’s library, and who is herself an accomplished photographer.

-Joe Maita, founder and publisher,. Jerry Jazz Musician

.

.

.

_________

.

.

Photographer Lee Tanner

____________________________

Lee Tanner began using a camera as a teenager in New York City. An avid jazz fan from the age of eight and inspired by the jazz photography of Gjon Mili, Bill Claxton, Herb Snitzer, and Herman Leonard, he turned to documenting the jazz scene with a love for the music comparable only to his creative drive for visual expression. Photography, however, was only an avocation.

After graduation from college and a short tour in the U. S. Army, Tanner undertook scientific graduate studies leading to a career in metallurgical research. His career in science proceeded in parallel with the photography of jazz musicians for more than 40 years. Tanner’s scientific work involved frequent travel and he took every opportunity to capture the jazz scene on film in all the cities he visited in the United States and Europe. While living in Boston in the sixties, Tanner turned to video presentation, producing a live, impromptu music series entitled “Mixed Bag “on the PBS channel WGBH.

Downbeat was the first magazine to publish Tanner’s work in 1958, and later his pictures appeared on the pages of many other journals, including Rolling Stone, Jazz Magazine (Paris), Jazz Times, American Photo and Popular Photography. They also graced the jackets for LP and CD records produced by the Atlantic, Sony/Columbia, Verve, Fantasy, Rhino and Prestige recording companies.

Tanner has had numerous one-man shows in galleries and jazz clubs across the country including The Jazz Gallery in New York City, and Vision Gallery, Kimball’s East and Yoshi’s in the San Francisco Bay area. Recently retired from research, Tanner now devotes full attention to photography and to curating a series of group photographic exhibits entitled “The Jazz Image.” Pomegranate Art Books and Friedman/Fairfax Publishing Co. have published several collections of his work in books, posters and calendars. The recent books from Friedman/Faifax are Images of Jazz and Images of the Blues. Images of Jazz also includes a 17-track CD that Tanner compiled from theSony/Columbia archives.

Tanner shares his memories and thoughts about his life in jazz in an interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

____________________________

All photos copyright Lee Tanner unless otherwise noted.

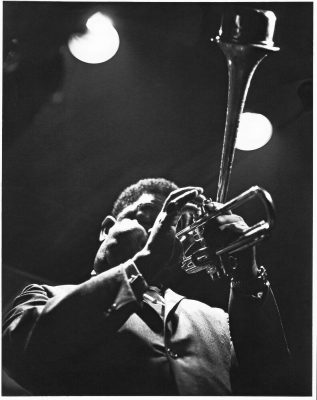

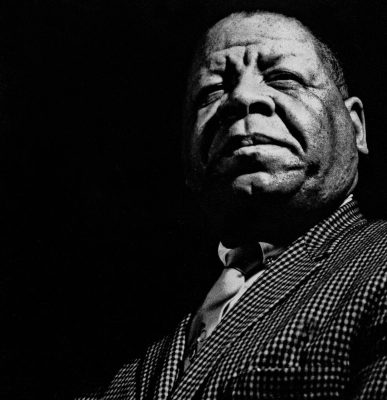

Cootie Williams

.

_____________

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

LT They were baseball players for sure. My favorites were Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio. When I first started listening to jazz, the player who really got me excited was soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet, who was very popular in Boston, where I grew up.

JJM Who were your photographic mentors?

LT I would say Herman Leonard initially, and then Bill Claxton as time went on, were the ones who really got me interested in photography. Leonard was publishing in Metronome magazine in the mid-forties, and then Claxton’s photos started appearing on the Pacific Jazz Records LP covers a few years later. In addition, my introduction to jazz photography came in Life magazine in 1944. Photographer Gjon Mili hosted an all-night jam session in his New York studio which included just about everybody in jazz, Basie, Ellington, Dizzy, Lester Young. The resulting photographs are classics. A bit later, Mili made a superb short film called “Jammin’ the Blues” that included Lester Young, Illinois Jacquet and Harry Edison.

JJM I was fortunate enough to meet Herman Leonard a few years ago…

LT Yes, he is a delightful person and a superb artist. Many of his first pictures were taken during rehearsals in the afternoons at New York’s Royal Roost. In those days the owners would hang his prints along the stairway that led down to the club.

JJMWhat photograph marked the birth of jazz photography?

LT Charles Peterson’s work in the late 30’s preceded Mili’s prints in Life. Peterson was actually a musician himself. He played guitar and banjo, and was in Rudy Valee’s orchestra. Because Peterson was starting a family in the thirties, he decided to get off the road and take up a new career. He met the renowned photographer Edward Steichen in New York, who encouraged him to go to photography school. Peterson soon was creating absolutely wonderful pictures of jazzmen in the clubs. By 1935, his work began showing up in Life, Town & Country and Vogue on a regular basis. They were taken with a large press camera using auxiliary lighting from flash units in the same way that Mili, Herman Leonard and Bill Gottlieb did a bit later.

JJM Do you remember who the people in the photos were?

LT Yes, Peterson knew the Dixieland players from Chicago: Pee Wee Russell, Eddie Condon and Bud Freeman, as well as Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Hot Lips Page and Sidney Bechet. He also shot many Commodore Record sessions including those with Billie Holiday. He took an apartment on the second floor of a 52nd Street brownstone walk-up above the jazz clubs and would spend his days working as a commercial photographer, and in the evenings he would go out to see his musician buddies and take pictures. There is a very good book of his prints available called Swing Era New York.

JJM When I was a young man, I loved jazz, but so much of the hook for me was the culture that was so wonderfully captured in the photographs of the era. They made quite an impression on me. Did you have a similar experience?

LT Yes, the same. I was listening to the music on Boston radio but I hadn’t seen anybody playing until I went to the rather formal big-band stage shows at the RKO Boston Theater. I was still too young to go to jazz clubs, and it was pictures like those taken by Peterson that showed me musicians playing informally in the dimly lit clubs. This had only become possible in the thirties with the invention of the flash bulb in 1931. Photography continued to advance rapidly through the WWII years and, by the mid-forties, one could obtain images without the use of flash units. This was a monumental breakthrough – the era of available-light photography had begun – and it was ideally suited to photographing the jazz scene.

JJM Then you could actually take pictures in a darker environment

LT Yes.

JJM How did jazz make such an impression on you?

LT I listened to music as a child. My family was always listening to the symphony orchestras and opera on the radio. Arturo Toscanini had an orchestra on NBC and classical music was greatly appreciated. The swing big bands were also playing on the radio. So, you had regular radio programs featuring classical music during reasonable evening hours like eight or nine, and then the marvelous late-night broadcasts when you could catch the Basie, Goodman and so many other great bands. Radio was an essential connection to the jazz artists of the day.

JJM When did you first begin photographing jazz musicians?

LT It wasn’t until the fifties, after I saw Leonard’s and Claxton’s work. Another photographer whose work made an impression on me was Herb Snitzer, who photographed for Metronome. I didn’t decide until then to pick up a camera and do it myself, but I spent about eight years getting ready for it.

JJM You indicated in your book, Images of Jazz, that it was in 1953 when you took some pictures of Bob Brookmeyer and Miles Davis, but you actually lost some of the negatives.

LT Sadly, I lost them all. The only thing I have is that one print of Brookmeyer that appears in the book. That was a remarkable night. There were frequent jam sessions going on at the time, usually downtown at Stuyvesant Casino and another spot, with traditional jazz musicians. I happened to attend one that took place in a ballroom somewhere around 45th Street and Eighth Avenue. I just walked in and the whole stage was crowded with be-boppers coming and going throughout the session. That was the first time that I photographed something like that.

JJM How did photographer Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibit affect you?

LT That exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art was the watershed experience for me and for so many other photographers it convinced me that I wanted to keep going with photography. It was absolutely amazing to walk into a museum and see such beautifully reproduced prints — some were ten feet high — and laid out in such a way that was just overwhelming. So many different subject matters were portrayed, including the works of several jazz photographers: Bob Willoughby, Hugh Bell and Ed Feingersh. That experience just energized my eagerness to participate. The exhibit book is still in print and is a must for any aspiring photographer.

The French were really the pioneers of candid and available-light photography. The exhibit included many of their prints. That was the most impressive work as far as I was concerned. For me, available-light photography was preferable to that of using auxiliary lighting sources. The ambient light was the important thing it was what brought life to the images also the movement and slightly out-of-focus, grainy quality all added to the emotional impact of the work. So, when I began photographing jazz musicians, I was looking for the same sort of emotional effects. When a musician really got into something special, I was often able to capture it .that is what brought great pleasure to the work. It essentially was an improvisation in the visual that went along with the improvisation of the music.

JJM What I am hearing you say is that there are similarities in the art of creating a photograph and a work of jazz

LT Oh, absolutely. It is an improvisational experience. If you are a candid photographer, you are essentially looking and grabbing what you can. There are quite a few photographers who set things up. It’s been disappointing to find that even some of the best candid photographers set up some of their pictures. But then again, I take artistic liberties after the fact in the darkroom.

JJM Nat Hentoff said of you, “Lee Tanner is the most consistent photographer who has the ability to find the person at the core of the player.” How do you find the person at the “core” of the player in your photographs?

LT I’m listening to the music and I generally sense when something profound is going on it’s at that point I will take pictures. Not all of the pictures are going to work, but in the course of shooting you can often capture something special. I really don’t know what the core of the individual is, I am just taking a picture and hopefully when the picture is developed, something unique is revealed. Essentially, I am interacting with the spontaneity of the musician, his music and hoping to capture the synergy.

JJM The photograph of yours that I most admire is the head shot of Duke Ellington in 1962. Can you talk a little bit about that picture?

LT That is a case where the darkroom helped a great deal. I took several pictures of him sitting at the piano, full-body in action. His facial expression was just right in one – and that was the only thing that was important – so I isolated it. I love to crop an image. It was important to allow all that black space in front of him to set the profile off. So, when I photograph, I just keep looking for things that strike me, but when I am in the darkroom, I take the image I have and perhaps try to get something else out of it. For some pictures there can be many powerful variations through cropping.

JJM What is your favorite picture?

LT My absolute favorite picture, probably, is one of Zoot Sims, where he is standing and not playing and I’m shooting from the back of the stage.

JJM You chose to put a dozen or so photos of Sims in your book

LT Yes, he was one of my favorites as a musician and as a subject. In that photo he was just at rest, waiting for his turn to solo, beautifully lit by the stage lights. That was a pose that was really characteristic of him. He just had a warm presence that was marvelous.

Also you could take endless pictures of Duke Ellington and you will almost always get very expressive ones. Wes Montgomery and Dizzy were that way also. On the other hand, photographing John Coltrane was more of a challenge because he was so intense and inwardly driven. You would see virtually the same pose and the only thing that would change was how much he really tightened the muscles in his face. It could be frustrating because it seemed at the time you really couldn’t take another picture of him without just repeating yourself. Photographer Chuck Stewart had more opportunities to have him as a subject and he got close to him. The result was that he was successful in getting a greater range of emotion from Coltrane. Primarily it was one of contemplation. It seemed that only rarely did he smile. There was one delightful picture of him with Johnny Hartman, taken by photographer Joe Alper. Their smiles just lit up the place. But there seem to be very few pictures like that. One could say that the intense Coltrane and the contemplative Coltrane were at his core.

JJM Which photo are you best known for?

LT Probably the Cootie Williams, and the Ellington head shot we spoke of. Those two, I would say. Of all of the pictures, Cootie’s face, and the way he played, you couldn’t go wrong. It worked like a charm.

Probably the Cootie Williams shot on the cover of Images of Jazz, and the Ellington head shot we spoke of earlier. Those two, I would say, of all of the pictures. Cootie’s powerful face, and the way he played, you just couldn’t go wrong it worked! I have to go back to what you asked me earlier about my favorite photo, and I would have to add the one of Johnny Hodges playing. He’s in full flight there. I have such a connection with him as far as his music is concerned. His was the way to play ballads and blues on the alto saxophone! As great as Charlie Parker was, if you asked me who the greatest alto player in the world was, I would still say Johnny Hodges.

JJM Who are some of the musicians you missed out on photographing?

LT I walked away from Louis Armstrong at a Newport Jazz Festival when I could have taken so many good pictures. But, at that time I was so fed up with listening to “Hello Dolly”. There is nothing more to say other than that was a very large mistake on my part. If all things were equal, if I also had one picture of Lester Young, I would be very happy.

JJM Billie Holiday historian Farah Griffin recently told me that the current interest among corporate America to market jazz is “not about a living artist but about a certain moment that becomes about a kind of elegance and class as well as hipness that is very American. So these characteristics of class of jazz are used to sell products.” When you took these photos years ago, could you have known that your work would be part of a uniquely American style that corporate America would feed upon?

LT No, I just followed my passion in the music, but I was shooting when that was an evolving concept. The record companies, particularly the small jazz record companies, were the first ones to utilize this type of photography. Prior to the LP era, the only products that ever got packaged with illustrations were collections of classical music recordings. One photographer that played a part in this was Robert Hupka, who took many photographs of conductor Toscanini. These may well have been the first available-light photographs of a musician and, as such, was a precursor to jazz photography. Hupka had an eye for this sort of thing, and if he had done it with jazz he would have accomplished the same thing.

Prior to that, there was very little that went into the marketing of the music because the packaging for 78-rpm records was just a sleeve with a hole in it. Then the small jazz companies started to pick up on it. The photographer Bob Parent contributed work to Savoy, and it became apparent that this was a terrific way to market the new LP’s. Blue Note also jumped in because one of the owners, Francis Wolff, happened to be an excellent photographer. Their LP jackets of course became a jazz LP design standard. Then, popular music/rock & roll just took off and the creation of record jacket art became a major activity. It went in all directions and much of it was, at best, mediocre. The jazz photography LP jacket design was in my view the most successful.

JJM William Claxton was instrumental in the success of Chet Baker in particular, and west coast jazz in general

LT The owner of Pacific Jazz Records saw Claxton’s first prints of the Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Baker and immediately hired him as his house photographer. He gave Bill free reign in developing the visual identity of his label. This soon became the overall identity of “West Coast Jazz”. In addition, Claxton was indeed responsible for Chet Baker’s success as much as Chet Baker’s musical abilities, which were quite marvelous at times. Claxton said when he went into the recording sessions he couldn’t take his eyes off of Baker who was so obviously photogenic. Claxton was a commercial photographer, and he understood the power of images like those of Baker. Baker appeared at just about the same time as James Dean and he connected with the public in quite the same way. Bill took full advantage of his persona.

JJM Talk a little about your experience with Coltrane’s A Love Supreme

LT That is producer Bob Thiele’s photograph on the cover. He was reviewing my 1963 Coltrane pictures from the Jazz Workshop in Boston at the time of the A Love Supreme. recording. These were presumably being considered for the cover. At the last minute, Thiele decided to put his own photograph on the cover. When the very next Coltrane recording came out, The John Coltrane Quartet Plays, my pictures were on that jacket.

JJM Do you remember the photograph that was going to be used on A Love Supreme?

LT No, I don’t know which one he was going to use. It was just a matter of, yes, he had them and, yes, he was looking at them, and so forth, but he didn’t even get to the point of making a choice.

JJM Prior to your being notified by Thiele that he was going to put his own photograph on A Love Supreme, did you have any sense that this would be a special Coltrane album?

LT No. I don’t recall that there was any prior indication of something special being recorded. I appreciated Coltrane’s ability and knew how intense his music could be but, I was not an avid fan. Thus, I may have been out of touch with that information. I was at the Jazz Workshop for four of the seven nights he played, but I was not aware of anything being beyond what he normally played which was very powerful music in itself.

JJM You are working on a very special project.

LT Yes, I have put a book together, The Jazz Image – Masters of Jazz Photography, that is a collection of prints from 24 photographers. It covers the period 1935 through 1965 and begins with the work of Charles Peterson followed by Gjon Mili, and then Gottlieb, Herman Leonard, Claxton, Bob Willoughby and on and on. I also include photos by a couple of Danish photographers, Jan Persson and Ole Brask, as well as the marvelous American photographer Dennis Stock, and rarely seen photos by Carol Reiff.

While compiling the photos, I didn’t want to necessarily go with all the iconic images, although there are quite a few of them included. You can’t, for example, pick Herman Leonard’s pictures without picking his Dexter Gordon or Duke Ellington shots. When choosing Claxton photos, the picture of Chet Baker I chose is one where you don’t even see his face — the shot is from above. Another marvelous Claxton picture is of Paul Desmond playing piano and laughing his head off. An absolutely superb photo. If anybody got the inner core of a musician, Claxton got to it with Desmond.

I use photos by another West Coast photographer, Jerry Stoll, who took many pictures at the Monterey Jazz Festivals since its inception. His picture of Stan Getz and Jimmy Raney playing just jumps off the page at you. There is another of Dave Brubeck, looking at his bass player while he is sitting at the piano with one hand on it, shot from above and from back stage. It too has a marvelous feel about it. I attempted to collect very special pictures using my photographer’s eye and my lifelong appreciation of the music. These are some of the best of the best from my friends and colleagues. We look forward to the book being published soon.

Images of Jazz

by

Lee Tanner

.

.

_____

.

.

(The book Lee Tanner described in this 2002 interview was published in 2006)

.

The Jazz Image:

Masters of Jazz Photography 1935 – 1965

by

Lee Tanner

.

.

This interview took place on July 29, 2002, and was hosted and produced by .Jerry Jazz Musician .editor and publisher Joe Maita

.

.

__________

.

.

The following collection of photographs by Lee Tanner are published with the consent of Mr. Tanner’s daughter Lisa Tanner, for which we are extremely grateful

.

.

Chet Baker

The Jazz Workshop, Boston, 1966

.

.

Nina Simone

.

.

Earl Hines

WBZ-TV, Boston, 1963

.

.

The Ellington Band with guest soloist Gerry Mulligan

Boston Globe Jazz Festival, Boston, 1967

.

.

Ray Nance

The Fenway Theater, Boston, 1958

.

.

Illinois Jacquet

WGBH-TV, Boston, 1966

.

.

Dave Lambert, Annie Ross, Jon Hendricks

Columbia Recording Studios, New York, 1962

.

.

Dizzy Gillespie

The Jazz Workshop, Boston, 1963

.

.

Max Roach

Kimball’s East, Emeryville, California, 1991

.

.

John Coltrane

.

.

Melba Liston

Connolly’s, Boston, 1962

.

.

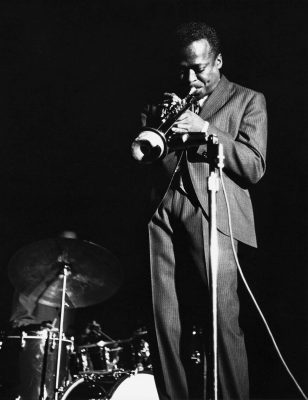

Miles Davis

.

.

Rahsaan Roland Kirk

Boston Globe Jazz Festival, Boston, 1967

.

.

Weather Report

Boston Common, 1972

.

.

Wes Montgomery

.

.

Abbey Lincoln

Newport Jazz Festival, Newport, 1965

.

.

Charles Lloyd and Paul Motian

WGBH-TV, Boston, 1968

.

.

Art Blakey

.

.

Milt Hinton

.

.

Art Farmer (with Roy Haynes)

WGBH-TV, Boston, 1967

.

.

Carla Bley

Herbst Theater, San Francisco, 1994

.

.

Charles Mingus

The Five Spot, New York, 1962

.

.

Coleman Hawkins

Connolly’s, Boston. 1958

.

.

Count Basie

.

.

Dizzy Gillespie (with James Moody, Kenny Barron, Rudy Collins, Chris White)

Lennie’s-on-the-Turnpike, West Peabody, Massachusetts, 1963

.

.

Eric Dolphy

Connolly’s, Boston, 1960

.

.

Grant Green and Clifford Jarvis

WGBH-TV, Boston, 1966

.

.

Jimmy Rushing and Budd Johnson

WGBH-TV, Boston, 1966

.

.

Jimmy Cobb

.

.

Henry “Red” Allen

Connolly’s, Boston, 1958

.

.

Sonny Stitt

.

.

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Connolly’s, Boston, 1962

.

.

Miles Davis

.

.

Thad Jones – Mel Lewis band with Jimmy Owens on trumpet.

Boston Globe Jazz Festival, Boston, 1967

.

.

Art Blakey

.

.

Dizzy Gillespie

.

.

To visit Tanner’s website and view more of his work, click here.