.

.

.

…..For many of us, the photography of Herman Leonard is our first link to jazz. Ellington in Paris, Dexter with a Chesterfield, a youthful Miles, Armstrong in New York — Leonard’s work plays an important role in our appreciation for the music and its artists, and are lasting documents to its glorious, honored past.

…..As a frequent witness and chronicler of some of the world’s great jazz performers and performances, Leonard has a unique perspective on the music.

…..In a January, 2000 interview, Leonard shares stories about his work, and those he photographed. Our discussion takes place as he releases his book Jazz Memories.

.

___

.

…..Jerry Jazz Musician appreciates Herman Leonard Photography, LLC, for allowing our use of the Herman Leonard photographs within this interview.

.

.

___

.

.

.

copyright Herman Leonard Photography, LLC

.Dexter Gordon, Royal Roost, New York, 1948

.

.

.

___

.

.

JJM. Your work and William Gottlieb’s has been so influential in my life, getting me interested in not only the music but in the whole culture of this incredible music…

HL. Thank the guys that play the instruments, not us!

JJM. How did you get involved with photography?

HL. It was my brothers fault. When I was a kid, in the 1930s, we didn’t have Playboy and Penthouse, but we took some pictures of his beautiful wife with very little clothing on I came across it when I was 11 years old, and it stunned me.

So, my brother loaned me a camera and I took some pictures of my friends playing baseball, and suddenly I was popular, because I was giving them the prints. That’s how it all started.

JJM. Simultaneous to this, did you have an interest in music as well?

HL. Only girls

JJM. So, just girls? Not girl musicians?

HL. No, I didn’t have a particular interest in jazz at that stage. It was a bit later than that, when I was about 14 or 15.

JJM. What happened then?

HL. I was exposed to a lot of classical music. My father and mother were both very interested in music, but they were always playing Beethoven and Bach and that sort of thing. One day I had the radio on and I heard a Louis Jordan thing, and I heard an early Nat Cole song, “Straighten Up and Fly Right.” When I heard the rhythms, it made me feel good, and I said, “Hey, this is happy, feet-tapping music!” That’s how I got interested in that form of music.

JJM. Tell me where you grew up?

HL. I grew up in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and I left there when I went to college, and I never went back to live there.

JJM. You went to college in Ohio?

HL. Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. In those days that was the only university that gave out a degree in photography.

JJM. Is that right? In the entire country?

HL. Yes, in the whole country. It wasn’t recognized as an art form of any kind, so they didn’t give any degrees.

JJM. This was right after the war?

HL. That’s right. Actually I went to the university before the war in 1940, and finished two years there, and then I went to the war and came back in 1945 and finished my college there, and graduated in 1947.

JJM. Did you take some pictures while you were in the service?

HL. Yes. I wasn’t an active photographer. The army failed me when they gave me a test on photography, and they turned me into a medic, and I did anesthesia in Burma on the Chinese troops. We didn’t have any fighting troops in Burma, we only had service and support troops, and I was part of that group. We were attached to the Chinese Army, which were fighting the Japanese in Burma.

JJM. Did you take many photographs during that time?

HL. No. It was very difficult. When you are fighting a war, unless you are an active photographer, you can’t pay attention to equipment and the film and the humidity and all of that. Sometimes we would be out there for two or three months and we would be lost, because there were no roads. We were supplied by air, and sometimes they couldn’t find us. I took pictures, many of which have been lost since then. I wish I had done more but there was no opportunity.

JJM. You must recall some of the photographs that you took at the time. Were they any good?

HL. Hell no. They were snapshots, like a news photographer would go around and shoot the pictures of whatever was going on. I shot pictures of some of the scenes we were involved with, and then we would come in contact with some of the mountain villages, and I would be able to photograph some of the things there at that time. That was always very interesting.

JJM. After the war, and after you graduated from college, then what happened?

HL. I went up to Canada to try to get a job with Yousef Karsh, who was and still is the greatest portrait photographer in the world. He did all the world’s most important people, and I admired his approach and his quality. But he wouldn’t hire me — he didn’t need anybody — but he suggested that if I could afford it I could study with him for six months. So I called my dad, and he supported me. I actually stayed a year with Karsh, a real turning point in my life because we photographed President Truman in the White House, Albert Einstein in Princeton University, General Eisenhower, Clark Gable, a whole bunch of people, which was really a mind blowing experience for me, not only to be with Karsh but to meet people of that stature.

JJM. That must have been quite an experience, beyond photographing them, but to be able to sit and talk with them…

HL. I was able to observe how Karsh handled all these different kinds of people. He was an absolute master at it.

JJM. He’s a portrait photographer

HL. That’s right. He’s now about 83 or 84. He’s not shooting much anymore, obviously. He’s done the most important portraits that have ever been done — Winston Churchill, everybody

JJM. So many of your most beloved photos took place in New York. How did you wind up in New York?

HL. After leaving Karsh, that’s where I wanted to go. I moved into a little studio in Greenwich Village and started photographing business executives doing a “Karshy” type approach to photography. Then I got some jobs with theater and dance companies photographing the theater, rehearsals, assignments for magazines. I got on as a stringer for Life and Look magazines.

JJM. Did you have an interest in jazz at this time?

HL. The whole time, yes. But I couldn’t afford to pay the entrance fee and I wasn’t a drinker, so I used the camera. They allowed me to come in in return for my giving them photographs. I began giving some prints to the musicians, and the whole friendship thing started.

JJM. Were you in some of the same jazz clubs simultaneous to when William Gottlieb would have been there? Were you ever shooting side by side?

HL. No. The funny thing is Bill stopped shooting in 1948 actively, and I started in 1947, but we never overlapped, and we didn’t know each other at that time. Bill was a reporter, he wasn’t a photographer, and he just took his camera and started shooting. He became a documentary photographer and got some unbelievable things, but I didn’t run across him.

JJM. You guys are the connection for many of us to that era…

HL. We didn’t know at that time — you never know, only later in retrospect. Either you wasted your time or your time was well invested.

JJM. What was your very first evening of photographing jazz? What was the club?

HL. Gee, I don’t remember. I have no idea. Well, I do remember the first pictures I took. I was still in the university, in early 1947. Norman Granz, the producer of Jazz at the Philharmonic Concerts brought a concert to Columbus, Ohio, and I ran up there from Athens to see this, and sat in the audience with my big newspaper events camera. The camera I used was a Speed Graphic, a big 4 x 5 thing, and from about 20 rows back (I was too scared to go up to the stage), I shot about four or five pictures of the performers on stage. Those were the very first shots I took, and I look at them today, and they’re not bad! They are a document of that moment.

JJM. When somebody mentions 52nd St, what goes through your mind? What is the image in your head of 52nd Street 40, 50 years later?

HL. If you could imagine, in today’s terms, going to one block where you would be able to see the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the U2, Def Jam, you name it, all within a couple-hundred yards of each other, playing on the same night, and you could go from one place to another that’s what it was like.

JJM. William Gottlieb told me something similar. Every time I hear that, and every time I hear of 52nd Street, it makes me wish I had lived in a different era

HL. I can’t say that your impression is wrong. Now that I have come this far, I can look back and have some perspective, and Bill and I were extremely lucky to have been born at that time and be exposed to this kind of thing. Today, I just haven’t found an element like that anywhere.

JJM. You and Bill had so much to do with perpetuating the art form

HL. You know, actually there are three of us, not just two, who, as far as I am concerned, documented jazz from the 1930’s to now in our own individual fashion. William Claxton is the other. So, Claxton, Gottlieb and myself constitute a range of photographers that overlapped each other. Claxton started shooting in the mid 1950’s I think, and he is still shooting. He did the west coast

JJM. Yeah, he did the Chet Baker’s and the Art Pepper’s

HL. That’s right. He covered the west coast, Gottlieb did the east coast earlier on, and I did the east coast following him. We just had a triple show in Berlin, in fact. It was the first time that we ever exhibited together. Someone in Berlin called me to do a show, and I had experience in exhibiting my stuff around the world, and people pay high compliments, but that’s about the end of it — they don’t buy anything. I wasn’t too enthusiastic about doing the single show in Berlin, so I suggested we do a triple show, so I got in touch with Claxton and Gottlieb, and they were all for it, and we had this wonderful show there. We each had about 90 pictures exhibited there. There was a tremendous response, although nobody sold anything because the Europeans are not art collectors, only in America and England, surprisingly enough. Even in France, where the people are fanatic about American jazz, non one buys the prints. That’s how we make our living, at this point.

JJM. Does it inspire you to do more shows like that, only in the U.S.?

HL. To be honest, I have lost a little bit of enthusiasm for photographing the musicians of today for several reasons. First of all, I don’t get quite as excited as I used to about the music that’s coming out. I have not heard anything innovative, anything really new and solid and good, not that I was fully aware of that when I first heard Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. I mean, I liked them, but I wasn’t aware of how important they would be later on. Today, I don’t hear anybody. I hear the young guys that are extremely proficient, technically fantastic, but there is no message, there is no soul in what they are doing. They are either rehashing the old stuff or there is just no content there.

Which brings to mind something that Dizzy Gillespie told me when I told him about an incredible alto player I heard on the radio that I thought was Charlie Parker, but it wasn’t. He was playing just as fast and efficiently as Parker, but there was something missing. I mentioned this to Dizzy and he said the trouble is that the kids grow up under more comfortable conditions, and they go to school, and they learn all the techniques, but, our school was the street, and we had something to say — there is a soul to it, a suffering in it. That’s the thing that sets Billie Holiday apart from all the other singers, she suffered so much, and the passion comes through in her singing. Today, I don’t hear any passion

JJM. There is a lot of honoring of the 1950’s era musician. Of the contemporary musicians, who would be easiest to be transported to 52nd Street in 1949? Marsalis?

HL. No, not Marsalis, and Wynton is a dear dear friend. I love him. He is a highly skilled musician who really knows his music backward and forward, which brings to mind a story. Gunther Schuller is a musician, arranger, conductor, composer, writer, and we were talking about Wynton, who I had just finished photographing a few days before. Gunther said to me, “This kid came to me a few years ago, and he was very cocky, and he wanted to do an audition for me. I thought I would throw something tough at him and asked if he can do the Brandenburg Concerto? He just blew right through it, without looking at music.” It just knocked Schuller out, how technically proficient he was — Wynton can play anything! I have heard him play the blues, I have heard him play everything, and he is wonderful, but it just doesn’t have the suffering behind it to be able to really punch through to that feeling that jazz has.

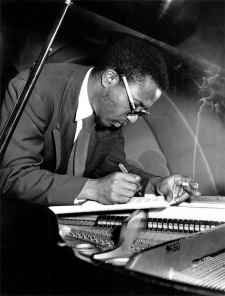

Thelonious Monk, New York, 1949

JJM. A favorite jazz musician is Thelonious Monk. I wonder if you have any special memories that you can share about Monk?

HL. The same as anybody else — he was a weirdo. I am not a musical expert, and I love what he did, because every note was a surprise, you just didn’t expect to hear that off-tone note or chord. He didn’t play many chords, actually, he just played notes. Somebody once said that he was unique because he played between the keys. Little pauses and hesitations where you don’t expect them. That’s exciting to me, that’s innovative, and he had his own feel, but as a person, you couldn’t talk to him.

JJM. He was difficult to connect with?

HL. Yes. He was somewhere up in orbit somewhere, all the time. Very fascinating man, big man, physically, imposing. When he stared at you, he stared through you. I liked him a lot, but I never got close to him personally, because he lived a rather isolated life.

JJM. Who was the most charismatic figure you photographed?

HL. Dizzy Gillespie. Dizzy was a great human being. He had such empathy for everybody and for the suffering. He was amazing, aside from being an incredible musician. Just an hour ago, I was listening to a Getz/Dizzy tune, and the ideas that he had, the variations that he would give to a standard were absolutely amazing. Dizzy was a comedian, a showman, a musician, and a humanitarian. He was a member of the Baha’i faith, and they believe that everyone is a brother, and Dizzy actively practiced this, all the way through. He was a good, fine gentleman. Dizzy and I got very close in the later years, although we were not too close in the early years, but that was a matter of geography really. We got along fine in the beginning, but in the later years, we seemed to connect in the same places at the same time. We used to hang out a lot, played a lot of backgammon — he was a lousy backgammon player. I had to let him win all the time! But funny, terrific guy.

JJM. As a young man, I remember feeling that Dizzy was a genuine human being who put himself out there as an ambassador for the music…

HL. To give you an example of what you’re saying, I was with him at a show in Paris, and, after the show, at 2:00 AM, I was backstage in the green room with him, and he is very tired, but he sat there for over two hours talking to a musician who was on junk and having trouble. I asked Dizzy about it, and he said he knew this guy for years and had been trying to help him. I asked him if he could see that there isn’t much he could to help, why spend so much time with him? He said that he knows what he is to them, and would like to help if he can. What’s another hour or two? This is the way the man was.

Dexter Gordon, Royal Roost, New York, 1948

JJM. So many of your photographs have that smoky, three o clock in the morning setting

HL. That’s the way it was. Essentially, all these pictures in the beginning I just shot for myself, they were not assignments. I never made any money on the jazz pictures until 40 years later

JJM. Your photo of Ellington in Paris, performing onstage in the spotlight…What are the circumstances of that photograph?

HL. That was shot at the Olympia Theatre in Paris. Piano players are very difficult to photograph because you only have two angles where you can see both their face and their hands on the keyboard — from the right or from the left, you cant see them from any other angle. You can’t shoot them from the front, because you don’t see the hands on the keys. Every time you shoot from the audience point of view, you are always going to get the same thing, depending on what’s behind him. For this photo, I went backstage through the curtains toward the audience, and that’s how I got the spotlight like that.

JJM. You got connected with Marlon Brando Was he a jazz fan?

HL. Yes, he was a jazz fan! The only reason I met him was because I had by sheer luck photographed a girl who lived around the corner from me in the Village, who turned out to be his girlfriend, and she announced to me that he was in town, looking for a photographer to go with him and his film company on a research trip. Every photographer in America wanted that assignment — guys from Life and everybody — and I told her that I take portraits and do jazz photos, and she said to go see him. So I went to see him at the hotel, which was on a Wednesday. I laid out the pictures and he liked them, and he looked at me and he said, “Can you leave Friday?” Two days later! I had a business in New York at the time, a studio and an assistant — the whole thing — but I said, “Yes!” I packed my bag and we took off from Los Angelses. There were four of us on the trip, Brando, myself, a film producer by the name of George England and a writer named Stewart Stern. We had this idyllic dream trip, sponsored by Marlon Brando, and we just hung out together for all those weeks. It was an invaluable experience.

JJM. Did you get out to any jazz clubs with him?

HL. Only when he came to Paris. After we did that trip, he went to Japan and did a film called Teahouse of the August Moon, and I came back to New York. When I eventually moved to Paris, every time he came through we’d meet and hang out and go to the clubs.

JJM. You have had quite a life!

HL. I have had a ball, and still having a ball! I just recently moved to New Orleans and it’s a whole new lease in life.

.

_____

.

by

Herman Leonard

.

.

This interview took place in January, 2000, and was hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician founder and publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.