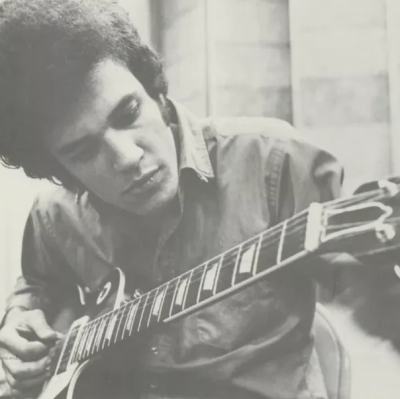

The correct answer is Mose Allison!

Not unlike his namesake, Luther Allison, pianist Mose Allison suffered from a “categorization problem,” given his equally brilliant career. Although his boogie-woogie and bebop-laden piano style was innovative and fresh-sounding when it came to blues and jazz, it was as a songwriter that Allison really excelled. Allison‘s songs have been recorded by the Who (“Young Man Blues”), Leon Russell (“I’m Smashed”), and Bonnie Raitt (“Everybody’s Cryin’ Mercy”). Other admirers have included Tom Waits, John Mayall, Georgie Fame, the Rolling Stones, and Van Morrison. But because he always played both blues and jazz, and not one to the exclusion of the other, his career suffered. As he himself admitted, he had a “category” problem that lingered throughout his career. “There’s a lot of places I don’t work because they’re confused about what I do,” he explained in a 1990 interview in Goldmine magazine. Despite the lingering confusion, Allison was one of the finest songwriters in blues of the 20th and early 21st centuries.

Born in Tippo, Mississippi, on November 11, 1927, Allison‘s first exposure to blues on record was through Louis Jordan recordings, including “Outskirts of Town” and “Pinetop Blues.” Allison credited Jordan as being a major influence on him, and also credited Nat “King” Cole, Louis Armstrong, and Fats Waller. He started out on trumpet but later switched to piano. In his youth, he had easy access, via the radio, to the music of Pete Johnson, Albert Ammons, and Meade “Lux” Lewis. Allison also credited the songwriter Percy Mayfield, “the Poet Laureate of the Blues,” as being a major inspiration on his songwriting.

After a stint in college and the Army, Allison‘s first professional gig was in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1950. He returned to college to finish up at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, where he studied English and philosophy, a far cry from his initial path as a chemical engineering major.

Allison began his recording career with the Prestige label in 1956, shortly after he moved to New York City. He recorded an album with Al Cohn and Bobby Brookmeyer, and then in 1957 got his own record contract. A big break was the opportunity to play with Cohn and Zoot Sims shortly after his arrival in New York, but he later became more well known after playing with saxophonist Stan Getz. After leaving Prestige Records, where he recorded now classic albums like Back Country Suite (1957), Young Man Mose (1958), and Seventh Son (1958-1959), he moved to Columbia for two years before meeting up with Nesuhi Ertegun of Atlantic Records. He recalled that he signed his contract with Atlantic after about ten minutes in Nesuhi‘s office. Allison spent a big part of his recording career at Atlantic Records, where he became most friendly with Ertegun. After the company saw substantial growth and Allison was no longer working directly with him, he became discouraged and left. Allison also recorded for Columbia (before he began his long relationship with Atlantic), and the Epic and Prestige labels.

Allison‘s discography is a lengthy one, and there are gems to be found on all of his albums, many of which can be found in vinyl shops. His output after 1957 averaged at least one album a year until 1976, when he finished up at Atlantic with the classic Your Mind Is on Vacation. There was a gap of six years before he recorded again, this time for Elektra’s Musician subsidiary in 1982, when he recorded Middle Class White Boy. After 1987, he recorded with Blue Note/Capitol. His debut for that label was Ever Since the World Ended. Allison recorded some of the most creative material of his career with the Blue Note subsidiary of Capitol Records, including My Backyard (1992) and The Earth Wants You (1994), both produced by Ben Sidran. Also in 1994, Rhino Records released a box set, Allison Wonderland. Allison‘s first new studio album in some 12 years, the Joe Henry-produced The Way of the World, appeared from Anti early in 2010. It would be Allison‘s final studio album; he died in November 2016 at the age of 89.

— Richard Skelly, for the All Music Guide to Jazz

Play Another Jazz History Quiz!