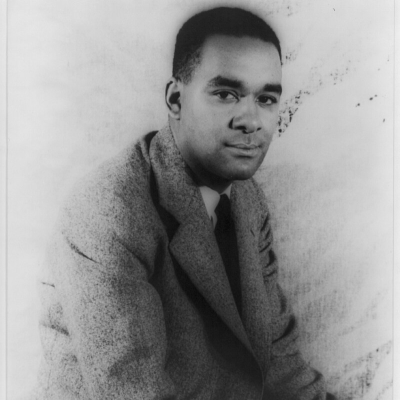

The correct answer is Charlie Haden!

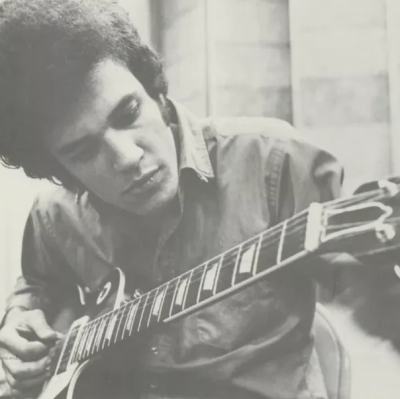

As a member of saxophonist Ornette Coleman’s early bands, bassist Charlie Haden became known as one of free jazz’s founding fathers. Haden never settled into any of jazz’s many stylistic niches, however. Certainly he played his share of dissonant music — in the ’60 and ’70s, as a sideman with Coleman and Keith Jarrett, and as a leader of the Liberation Music Orchestra, for instance — but for the most part, he seemed drawn to consonance. Witness his trio with saxophonist Jan Garbarek and guitarist Egberto Gismonti, whose ECM album Silence epitomized a profoundly lyrical and harmonically simple aesthetic; or his duo with guitarist Pat Metheny, which had as much to do with American folk traditions as with jazz. There was a soulful reserve to Haden’s art. Never did he play two notes when one (or none) would do. Not a flashy player along the lines of a Scott LaFaro (who also played with Coleman), Haden’s facility may have been limited, but his sound and intensity of expression were as deep as any jazz bassist’s. Rather than concentrate on speed and agility, Haden subtly explored his instrument’s timbral possibilities with a sure hand and sensitive ear.

Haden’s childhood was musical. His family was a self-contained country & western act along the lines of the more famous Carter Family, with whom they were friends. They played revival meetings and county fairs in the Midwest and, in the late ’30s, had their own radio show that was broadcast twice daily from a 50,000-watt station in Shenandoah, Iowa (Haden’s birthplace). Haden debuted on the family program at the tender age of 22 months after his mother noticed him humming along to her lullabies. The family later moved to Springfield, Missouri, and began a show there. Haden sang with the family group until contracting polio at the age of 15. The disease weakened the nerves in his face and throat, thereby ending his singing career. In 1955, Haden played bass on a network television show produced in Springfield, hosted by the popular country singer Red Foley. Haden moved to Los Angeles and by 1957 he’d begun playing jazz with pianists Elmo Hope and Hampton Hawes and saxophonist Art Pepper.

Beginning in 1957, he began an extended engagement with pianist Paul Bley at the Hillcrest Club. It was around then that Haden heard Coleman play for the first time when the saxophonist sat in with Gerry Mulligan’s band in another L.A. nightclub. Coleman was quickly dismissed from the bandstand, but Haden was impressed. They met and developed a friendship and musical partnership, which led to Coleman and trumpeter Don Cherry joining Bley’s Hillcrest group in 1958. In 1959, Haden moved to New York with Coleman; that year, Coleman’s group with Haden, Cherry, and drummer Billy Higgins played a celebrated engagement at the Five Spot, and began recording a series of influential albums, including The Shape of Jazz to Come and Change of the Century. In addition to his work with Coleman, the ’60s saw Haden play with pianist Denny Zeitlin, saxophonist Archie Shepp, and trombonist Roswell Rudd. He formed his own big band, the Liberation Music Orchestra, which championed leftist causes. The band made a celebrated, eponymously titled album in 1969 for Impulse!

In 1976, Haden joined with fellow Coleman alumni Cherry, Dewey Redman, and Ed Blackwell to form Old and New Dreams. Also that year, he recorded a series of duets with Hawes, Coleman, Shepp, and Cherry, which was released as The Golden Number (A&M). In 1982, a re-formed Liberation Music Orchestra released The Ballad of the Fallen(ECM). Haden helped found a university-level jazz education program at CalArts in the ’80s. He continued to perform, both as a leader and sideman. In the ’90s, his primary performing unit became the bop-oriented Quartet West, with tenor saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent, and drummer Larance Marable. He would also reconstitute the Liberation Music Orchestra for occasional gigs.

In 2000, Haden reunited with Coleman for a performance at the Bell Atlantic Jazz Festival in New York City. Throughout the 2000s, Haden remained prolific, working with Gonzalo Rubalcaba on Nocturne and Egberto Gismonti on In Montreal in 2001; collaborating with Brad Mehldau, Michael Brecker, and Brian Blade on the following year’s American Dreams, and John Taylor on 2004’s Nightfall. That year, Haden returned to Montreal for the Joe Henderson tribute The Montreal Tapes with Henderson and Joe Foster and teamed up with Rubalcaba again for Land of the Sun. The Liberation Music Orchestra reunited for 2005’s Not in Our Name, which was arranged and conducted by Carla Bley, and Haden celebrated his 70th birthday with Heartplay, a date with guitarist Antonio Forcione. Helium Tears, a 1988 session with Jerry Granelli, Robben Ford, and Ralph Towner, was released in 2006.

To continue reading Chris Kelsey’s biography of Charlie Haden on the All Music Guide to Jazz website, click here

_____

Play another Jazz History Quiz!