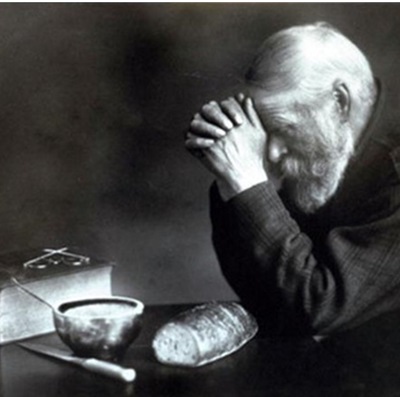

Gene Lees, 1959

photo by Ted Williams

________________________

Gene Lees is a well-known jazz chronicler. He is also a song lyricist, composer, singer, and author of more than a dozen volumes of jazz history and criticism, including the highly acclaimed Cats of Any Color: Jazz Black and White.

In You Can’t Steal a Gift, Lees writes of his encounters with four great black musicians: Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, Milt Hinton, and Nat King Cole. Equal parts memoir, oral history, and commentary, each of the main chapters is a minibiography weaving together conversations Lees had with the musicians and their families, friends and associates over several decades.

An underlying theme is the impact racism had in these four musicians’ lives and careers, and their determination to overcome it. Lees discusses his book, racism, his friendship with Peggy Lee, and the gifts of Nat Cole.

Interview by Jerry Jazz Musician contributing writer Paul Morris.

________________________

JJM Please explain the title of your new book, You Can’t Steal a Gift?

GL It came from the alto saxophonist Phil Woods. When Phil was young and uncertain of his talent, he was troubled by people saying he was influenced by Charlie Parker. He asked Dizzy Gillespie about the accusation that he had stolen Charlie Parker’s music, and Dizzy said, “You can’t steal a gift. Bird gave his music to the world and if you can hear it you can have it.” When I was looking for a title to the book, I was talking to Phil about it and he came up with that line and I thought it was marvelous. Music is a gift, after all — all music.

JJM I enjoyed what you wrote about Chicago and its importance to jazz. It almost amounts to a fifth profile in the book.

GL Yes, it almost does. Chicago was a very important, formative city in jazz history, and that has been somewhat neglected. There has been so much emphasis put on New Orleans, but the truth is that Louis Armstrong, who is the major founding figure in the concept of the jazz solo, brought his craft into maturity in Chicago, even though he was from New Orleans. An enormous number of New Orleans musicians gravitated to Chicago, and then Chicago began to develop its own. Furthermore, it acted as a magnet for musicians from all over the country. The number of musicians from the midwest, like Bix Beiderbecke, who went to Chicago, and Woody Herman, who went to Chicago, Joe Williams, whose family went to Chicago, and Nat Cole was born in Alabama but his family moved to Chicago It was a magnet in the center of the country. There was so much made about the power of New York, everybody forgets that at that time Chicago was the second biggest city. It drew an enormous number of artists, particularly musicians. Chicago had a fellow named Captain Walter Dyatt, who taught at one of the black high schools there, and the number of musicians he trained, including Nat Cole, is just phenomenal.

JJM Is this Wendell Phillips High School?

GL Yes. Milt Hinton went there, Johnny Hartman, Johnny Griffin the number is enormous. He was a very effective teacher. One of the things I have discovered in jazz history over the years is that certain key schools developed enormous numbers of musicians, which leads us back to the question of the importance of education in our society.

JJM You have stressed the educational background and technical knowledge that’s necessary to be a good jazz musician.

GL Part of the myth of jazz, because it’s an improvised music and requires improvisation, is that these guys were ignorant of music. There have been a very few jazz musicians who played pretty much by ear – which doesn’t mean you have no talent, it means you don’t even need the written note, you can hear it. A few guys like Errol Garner and Wes Montgomery could not read music, but by and large, most jazz musicians have had very good schooling, which is to say that jazz musicians have almost all had classical training, whereas classical musicians have not had jazz training. That is why the jazz musicians, such as Andre Previn, are able to go on to be symphony composers and conductors. Mel Powell, the stride pianst James P. Johnson and Earl Hines all had very good knowledge of the classical repertoire. Something else to be kept in mind, “self-taught” does not mean “un-taught.” There are two or three composers, like Gil Evans and Robert Farnon, both of whom happen to be from Toronto, who trained themselves. They got scores and read them and studied them, and believe me, they know those scores as thoroughly as anybody from any conservatory. Farnon told me once, when he was first writing at age 15, he would write one part at a time, lining it up on the floor with papers spread all around him. He met Don Redman, who asked him if he had ever heard about writing on a single sheet of paper as a score. So when you say he was self-taught, sure, up to a point he was, but somebody showed him something along the way.

JJM There is a similar story about Benny Carter learning arranging by laying out parts on the floor

GL Yes. You know, a lot of guys did that! It’s a not uncommon phenomenon.

JJMOne of your profiles is of the bass player Milt Hinton, who died in 2000. His career spanned the majority of the history of jazz. You did a great job of allowing him to tell his story.

GL I have reached an age myself where I realize it is unlikely anyone is going to write a biography of Milt Hinton. It is possible, but not probable. If I don’t get some of this stuff down while I am still here, it is going to get lost. Those interviews with Milt, we conducted on the SS Norway during a jazz cruise to the Caribbean. Even my friends like Clark Terry, to get him settled down for an hour when he is traveling all the time, or myself settled down for an hour, is kind of difficult. Those jazz cruises gave me a chance to have talk with someone who is not able to get off that ship for a while. I had him trapped! Consequently, the interviews were very unhurried. I still have about five or six hours with Phil Woods that I haven’t transcribed yet. So, the interviews with Hinton ran about six hours of conversation. They are very thorough interviews because they had the time to do it.

JJM Dizzy Gillespie and Clark Terry are known for their humor on stage. You cite examples of their wit. You also point out that bop music was once criticized as “anti-social,” “sullen,” and “nervous.” Can you talk about that a little bit?

GL When we were used to a certain kind of jazz, when it was harmonically and rhythmically simpler, these guys became very sophisticated in handling this material. Like all artists in all fields, you get bored with your own techniques, and you want to push it onward. It’s like Charlie Parker said in an interview I heard where the interviewer asked what the musical revolution was all about, and Parker said, “Excuse me, we weren’t rebelling, we just thought that was the way the music should go.” So, it became harmonically a lot more sophisticated. It wasn’t more sophisticated than Ravel and Debussy, they had been doing it in France for 50 years, but it did go to that dimension. Also, one of the things they started doing was rhythmic displacement, which really goes back to Bach, and I know a lot of the bebop musicians were quite fascinated by Bach. Things start and stop in unexpected places and some people were absolutely upset by it. When I first heard it, I thought it was kind of crazy, but I pretty soon got used to what they were doing, and said, “Wow, this is pretty exciting stuff!”

JJMThe point about them trying to “rebel” doesn’t make sense, really, if you think about people who need to earn a living. These people were trying to sell records and earn a living and become popular.

GL Dizzy told me once that if he could make people laugh he could them more sympathetic to his music. That is what he did. Dizzy was a consummate humorist. I loved being around him just for his sense of humor. He had that gift, like Jack Benny,. He could walk on the stage and do nothing and make you laugh. This tended to make people take him not as seriously as Charlie Parker, because Parker was a tragic junkie. There is nothing in the jazz world that people love so much as being able to pity somebody. Pity for genius is the ultimate arrogance. They loved Bill Evans, not because he was one of the greatest musicians the world has ever known, but because he was a junkie and they could feel sorry for him. This is a really cruel streak in jazz criticism. Critics have often pitied people who are drunks or junkies rather than admiring them strictly for the talent and the scope of the development.

JJM You have some good documentation of the things he brought to jazz in the 1940’s

GL Yes, and he was also the major teacher. Bird didn’t teach anybody because he was too busy looking for a fix.

JJM You discuss the importance of education to Dizzy, to Clark Terry, and to Milt Hinton. They have all made it an important part of their careers, to teach other musicians on their way up.

GL I loathed and detested the Ken Burns Jazz documentary because there was no mention about Nat Cole. There is not much of Earl Hines either. Essentially, all of modern jazz piano comes out of Hines to Cole to all the people who came out Cole, such as Oscar Peterson, Horace Silver, Bill Evans, and so many others. This is one of the major streams in jazz history, is that flow of Hines to Cole, and it was not mentioned once in that atrocity of a program Burns put together. It was a total distortion of jazz history.

JJM One of the themes of your book seems to be the strength of character of musicians who had many reasons to hate whites but didn’t. You write that it doesn’t surprise you that musicians might hate whites. What does surprise you is there are so many that didn’t.

GL That is the truth. To grow up in America, if you are black in America, it may not be as bad as it once was 30 – 50 years ago, when you could not be black without being insulted every day.

JJM Regarding Nat Cole, you described numerous racist incidents that marred his career. Some of them were shocking, especially his early experiences in the South.

GL There was an incident that occurred a couple of days before I met him, in Alabama, where some white guys jumped on the stage and tried to kidnap him. They punched him out. It was a pretty ugly incident that made headlines. There is an interesting point here. When I was a kid growing up in Canada, a barber refused to cut Oscar Peterson’s hair, and I covered the story. It made headlines across Canada. In the U.S., a lynching wouldn’t even make headlines. Nat Cole’s story may have made some newspapers in America, but not nearly as much as Peterson’s haircut incident in Canada. I am not trying to make any moral claim for Canada, but racism was never as entrenched there. There is no reason for it to be. America’s racism is still the country’s major problem.

JJM You write about the influence of racism on Nat Cole’s stage persona. One of your comments is that his humorous, joking persona on stage was a way of deflecting the fire of white resentment.

GL I loved Nat Cole. I loved him as a pianist. I didn’t know him as well as I knew the other guys in the book, but I liked him very much as a man. It was impossible not to like him. But, when I examined his repertoire, I sat down and read his selection of tunes. I am not sure he did any of this consciously, but they weren’t the obviously romantic, erotic tunes Sinatra chose, for example. They tended to be rather humorous tunes which deflected the white male’s sexual resentment of him. Nat Cole was really the first major black romantic figure in American entertainment, singing love songs.

JJM People may be surprised that you also write he was number one as a pop entertainer.

GL Absolutely. I can’t remember the figures at the time, but certainly he was up there with Sinatra. He and Peggy Lee, their record sales built Capitol Records.

JJM Another interesting quote you use about Nat Cole, in comparing his style to Sinatra’s…Cole said “The band swings Frank, I swing the band.”

GL He really did say that, and every musician I have ever quoted that to believe he was right. Sinatra learned to bounce on the rhythm section, propelling him. Some people have such a strong rhythmic sense. Nat Cole is one, Joe Williams is another, Oscar Peterson is another. Their rhythmic pulse is so strong it will pull the entire band in with them. When I sing, I am in somewhat in the same school as Sinatra. The band will swing me. I can grab that pulse and stay with it, but Nat could make it happen.

JJM I have just been listening to some of the recordings with Billy May and he can pull his band along, and that is a quite a band.

GL Yes, Nat’s rhythmic sense was magnificent. Also, it was completely lazy. There is no push about it, he just lets it happen. It is like Roger Kellaway said when we were listening to him, he said the trick in the arts is to get out of your own way, and Nat Cole is never in his own way. It is a difference between trying to make the song happen and letting it happen.

JJM You write that Nat Cole’s life, for all its great moments, was ultimately sad.

GL I think it was. In the 1940’s, when his career really crested, he wanted to be an actor like Sinatra. He and Billy Eckstein both had ambitions toward film and were just never allowed to. He made two movies, one of which was just plain bad, a movie about W.C. Handy, and another one about the French foreign legion with Gene Barry, set in Vietnam.

JJM He was in Cat Ballou

GL Yes, but he only had a narrator’s commentary in that, and even then it was using a black man for humor.

JJM Almost a jester role.

GL It’s the “interlocutor commentator” on the action of the show. It is very effective by the way, but it is not taking the man himself seriously. Blacks in movies, the way they were treated in film, is they were comic figures. Put four black guys on a train, stewards on a car, and they could suddenly sing in perfect harmony. Or, Billie Holiday playing a maid. Society didn’t know what to do with blacks. I have been curious to see in recent years a very fortunate evolution of this. If you saw Philadelphia with Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington, except for a couple of minor references, you could remove entirely the fact that the lawyer is black. It doesn’t matter, it is irrelevant to the story. Time and again you will see current Denzil Washington movies and the color of the character is irrelevant to the story, race just doesn’t matter. This I consider a very wholesome, fortunate evolution in film. But it wasn’t that way in the 40’s.

JJM I believe you knew Peggy Lee. I wonder if you could comment on her passing and on her importance to jazz, especially as a jazz singer

GL Peggy was a very close friend of mine. At one time we talked on the phone every two or three days. First of all, I don’t care about the term “jazz singer.” Sarah Vaughan didn’t even like the term, she in fact resented it. She said, “I am just a singer.” Peggy was the greatest reader of lyrics of anyone I ever heard. In fact, I think she was even better than Sinatra, and Sinatra was about as good as it gets. She was a phenomenal interpreter of lyrics. She was like Montgomery Clift’s acting. What she was doing was so brilliant that you don’t notice it. There is a great line of Benjamin Disraeli in the 19th century. He said, “A gentleman is never seen to be working.” Truly great art, you don’t see the work that has gone into it. It just seems so natural that you don’t pay any attention to it, and Peggy’s art was like that. It sounded so casual and so careless, but by point of fact, it was utter mastery. She was one of the great vocal actresses of the last century. She had been in a semi-coma for nearly three years, and her death was a release. I didn’t even cry over her death. I probably did my mourning before she died because our conversations had ceased, and she had ceased to appear anywhere, at least to sing. She was a truly great artist. There is another one of my books, The Singers and The Songs, in which there is an extended portrait of her. She was wonderful.

JJM The second edition of that book is an expanded version of the first?

GL Yes, it was an expanded version. It is going to go out of print shortly and I plan to put the first and second volumes together as one volume.

JJM Is there anything about your book that we haven’t talked about that you would like to mention for readers to know?

GL I had written these portraits of four major figures in jazz and I just realized that they are four magnificent human beings who are very great musicians. They had every reason to be embittered people and they weren’t. They were generous, kind, good, and wholesome people who had a lot in common.

JJM I would appreciate it if you could give us some recommended CD’s on these four musicians. You write very interestingly about Nat Cole’s album, Penthouse Serenade, from the early 50’s, saying that if you had to have a list of desert island discs, that would be at the top.

GL Absolutely. There are so many records Milt Hinton is on, I couldn’t even begin to recommend. He was probably the most recorded bass player in New York. There is a record of Dizzy Gillespie’s – there are three of them, “Dizzy Gillespie in South America” is a recent release. The very first one on there, which I think is one of the greatest jazz albums ever made. The sound is not even that good, because it was done on old mono equipment, but the performances of the big band and Dizzy are just awesome! I can’t think of any album that Clark Terry is on that I wouldn’t recommend.

_______________________________-

.

Dizzy, Clark, Milt and Nat

by

Gene Lees

*

JJM Who was your childhood hero, Gene?

GL One of them was a cartoonist named Alex Raymond, who drew Flash Gordon. Another was Hal Foster, who drew Prince Valient. Another was probably cowboy star Ken Maynard. When I was about 12, I would say Bing Crosby. At 15, it was Frank Sinatra. I was very drawn to artists because I was going to be a commercial artist. My childhood heroes tended to be painters and graphic illustrators, like Gil Elvgren, who did commercial art and posters. Elvgren did pictures of pretty girls, and was also a pretty good artist. Also, Edgar Rice Burroughs, for the novels he wrote. I also enjoyed Ray Bradbury and science fiction writers. Tyrone Power because of “The Mark of Zorro.” I loved the romantic movies of the time, and of course I went to all of the cowboy westerns, and Saturday afternoon serials.

_______________________________

Gene Lees products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

Interview took place on February 6, 2002

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Nelson Riddle biographer Peter Levinson

*

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews