.

.

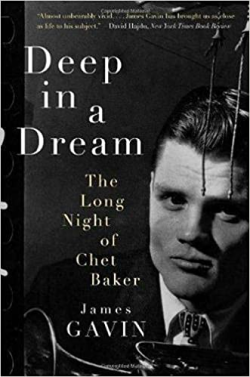

Michiel Hendryckx, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Chet Baker; Belgium, 1983

.

___

.

That trumpeter Chet Baker was a sensitive musician whose sound is a cherished part of the jazz landscape is well known. That he led a hard life is also pretty well known, perhaps even to the most casual music fan. His 1988 death from a fall out an Amsterdam window only added to the sad mystery surrounding his persona.

What was not known by most of us is the haunting depth of Baker’s self-destructive life; that he was an arsonist, a thief, a second-story man, a drug addict, an abusive husband and lover, a philanderer, a liar…need we go on? We could, you know.

Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker, is biographer James Gavin’s dark profile of Baker’s demise – a book so dramatic and compelling that it effectively becomes the reader’s personal vehicle for transport into Baker’s seductive, tormented, seedy world.

In our exclusive interview, Gavin talks with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita about the stark sadness that dominates his book, and indeed, Chet Baker’s life.

.

.

___

.

.

JJM Who was your boyhood hero?

JG Musically, my boyhood heroes were women. Early on, I was infatuated with Peggy Lee, as I still am. But my introduction to the music I love, and that I have written about for quite a few years, was the Andrews Sisters. I was born in 1964, and in 1974 Bette Midler had her first hit, “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” when she was doing the camp nostalgia routine that made her a star. “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” knocked me out. It opened a window to the past for me, and like most kids, I was looking for my own little world to escape into, and the past seemed like a safe haven. There are no surprises; you know exactly what’s going to happen. My Uncle John bought me an Andrews Sisters record, and that is probably why we’re having this conversation now. The Andrews Sisters turned me on to the swing era and the great singers it produced. Chet Baker wasn’t a part of that era; he came later.

JJM Why did you choose to write a biography on Chet Baker?

JG Desperation. In 1991, I published a book called Intimate Nights: The Golden Age of New York Cabaret. My tastes had moved forward about a decade, and now I was fascinated by the 1950s, which seemed so cool and sophisticated to me at my young age. The gigantic repression of that time, sexual and otherwise, gradually began to interest me too. At the time, I owned only two Chet Baker albums. One of them, which may still be my favorite, is Chet, a set of instrumental ballads with Bill Evans. I thought it was the best “make out” music I had ever heard, even though I hadn’t started making out yet! I found this music to be incredibly slow and sexy and hot – not cool, as everyone called him. When Chet made that album in the late ’50s, he was virtually a gutter junkie, and that surely helped break down his cool veneer. But I still wasn’t a great aficionado, I must admit. I knew the cliches of his life story: that he was a beautiful but tarnished golden boy from the 50’s with an androgynous singing voice that people debated about violently, and that a lot of people didn’t take him seriously as a trumpeter, either. I had a vague sense that he was extremely out of favor in the United States and had become as famous for his drug habit as he was for his music. I didn’t know much more about him, but I did know that no one had written a comprehensive book about him that tried to cut past all the myths. I was desperate to write another book, and in the fall of 1994, some angekl or devil flew onto my shoulder and whispered the idea of Chet. From that point on, I became as obsessed with him as anyone who had known him. I sold the idea to Knopf very quickly. The time was right. The documentary Let’s Get Lost had come out five years earlier, and Chet was becoming more popular in death than he had ever been in life. The Gap ad that read “Chet Baker Wore Khakis” came out around that time, and the records were starting to really sell. It was obvious that people were mystified by Baker and drawn in by all the mystery surrounding him. I sensed that there was a great detective story to be told. I was certainly right about that.

JJM Baker’s life is desperately sad. Were you as shocked by the sadness of his story as I was?

JG At times I was extremely depressed by it, but I can’t say I was shocked. Orrin Keepnews, the former co-owner of Riverside Records, was one of the first people I interviewed, in December of 1994. Orrin recorded Chet in the late ’50s, and he grew to hate him. Orrin said to me, “Do you have any idea what you’re getting yourself into?” I said, “Sure.” But I didn’t, not at all. I very quickly learned how messy this story was, mired in falsehood and almost hopelessly mythologized, to the point where its ugliness was made to seem romantic and glamorous. As I went on with my research, I realized that most of the famous stories told about and by Chet Baker were completely fictional, that many people who had known him had their own agendas and were not telling the truth. Because I had not known Baker and had never even seen him perform, I had no agenda of my own, besides trying to tell the truth. And the truth was much uglier than I had imagined. The paradox that fascinated me and a lot of people was, how could so much beauty come out of so much ugliness? When we look at our idols, we’re seeing a reflection of who we want to be. We don’t want to see monstrous flaws; we want to believe that a beautiful artist is also a beautiful human being. Most people just do not want to know the truth. It’s hard for certain people to read my book, because they want to believe that Chet was essentially the same romantic figure they hear on his records. He had elements of that romance in his personality, but the realities of life as a drug addict are not pretty.

JJM You wrote of Baker and bebop, “He plunged fully into the culture surrounding it: the burning drive to keep moving, the pleasure in shocking people, and later, the compulsion to self-destruct.” Who did Baker model himself after?

JG In my opinion, Chet Baker had little interest in the outside world, except as it related directly to his needs. He wasn’t modeling himself after other rebels Marlon Brando or Jack Kerouac or even Charlie Parker, because he lived in a bubble. Chet would never have seen himself as a part of any social movement. But his number-one musical hero was Miles Davis. I think it’s indisputable that if there were not a Miles Davis, there would not have been a Chet Baker as we know him. Chet himself said that Miles showed him the light — that if you were a trumpet player, you didn’t have to play loud, screeching, high notes as fast as you could squeeze them out. That is what people were accustomed to hearing in a trumpet player. It’s one of the reasons why, to this day, Chet is not taken seriously by a lot of people. As he said, his playing just sounded too easy to many listeners.

JJM In fact, there was a friend of Baker’s, a haberdasher named Charlie Davidson who said of Baker’s early success, “Half of it was physical attraction. I mean, what right did he have to be winning Downbeat polls over Miles and Dizzy and Clifford Brown? Everything was getting so out of proportion.” How did the black musicians of the fifties era, including Miles Davis, feel about Baker’s success?

JG They hated him for it, even though they usually avoided admitting that. Miles Davis made it pretty clear that he thought Baker had ripped him off. The black musicians saw a pretty white boy appearing on the Today show, on the Tonight show, winning the trumpet polls by a big margin after having seemingly come out of nowhere. It was easy to interpret his success as a slap in the face to black musicians like Miles who were better schooled than he was, who played with more obvious fire, who seemed stronger and had more obvious passion to express. Chet was the object of tremendous resentment at that time, and he knew it. I think this is one of the sources of all of the pressure that built up in him in the fifties, as he became an underground star.

JJM There was one man in particular who had a lot to do with him rising to this level, the photographer William Claxton. He wrote, “Chet was sort of a nice looking, athletic guy; he kinda looked like an angelic prize fighter. He had one tooth missing, so he looked a little dopey, and a sort of fifties pompadour in his hair, but then you put him in front of a camera and he became a movie star.” Claxton was very important to Baker’s career, wasn’t he?

JG If Bill Claxton had not taken the pictures of Chet that appeared on his earlycovers, I don’t think we’d be having this conversation, and I don’t think a major publisher would ever have commissioned a biography of Chet. His looks fit perfectly with his sound, especially his singing. Chet sang in a way that men – especially jazz musicians – were not supposed to sing then. The ’50s were an age of ironclad sex roles; men were men, women were women, and the gray area in between was off limits. To this day, you can hear Chet sing and not know whether he’s a man or a woman. The singing itself is so detached, almost numb. Bill Claxton captured that sense in his photographs. He caught everyone looking so cool, so pulled-together and trouble-free. Chet, of course, was actually a disaster waiting to happen.

JJM It was really the image of California. They weren’t smoking in a dusty, dark club…

JG Yes, they were outdoors, in the light. In those Claxton pictures, Chet could be thinking about anything or nothing. He looks perfect. His skin is like porcelain. His hair is perfect. His eyes are revealing nothing. People were mystified. His handsomeness was so soft, when jazz musicians were supposed to look tough. No wonder so many teenage girls were so infatuated with him. Chet drove a lot of women crazy.

JJM By all accounts, Baker was nothing but trouble. He was a junkie, a philanderer, not the least bit dependable, and possessed a terrible temper, even attempting murder. Ruth Young, one of Baker’s lovers, came to the conclusion that Baker “couldn’t stand women. He hated them all, including me.” Yet women stood by him. Why were women so vulnerable to Baker’s charms?

JG Both women and men were vulnerable to his charms. The image of the wounded artist — who creates great beauty out of great pain — is an extremely romantic one, especially in Europe. When someone reveals as little as Chet revealed, it suggests a mystery that’s crying out to be solved. People thought that somewhere inside his silence lay the key to that magical artistry of his.

JJM You talked about Europe and you claim that Baker “fit neatly into what Fellini viewed as a Dante-esque frenzy of moral and spiritual decay.” Maybe what you are saying is that not only women were vulnerable, but society, particularly European culture was vulnerable to him. There was more of a fascination with his self-destruction than his music over there.

JG I think his music and his image were indistinguishable in Europe. The Europeans revered Chet at a time when America had tossed him aside, with Chet’s cooperation, of course. Here in the States in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, Chet was looked down upon as a burn-out who had destroyed his gifts, thrown his life away. There was a very nice review of my book in the Toronto Star. The subtitle reads, “What a waste his life was.” That was and is the American attitude toward Chet. It really annoys me, as it did him, because how can you call a guy a waste when he’s recorded 150 albums and almost never stopped playing? That attitude reveals something quite unflattering about America. In Europe, Chet felt embraced, because most people didn’t treat him with disapproval — even when he deserved it. I think it was the pianist Enrico Pieranunzi who said in my book that in Italy, Chet was looked upon as a great artist with a great problem. Europe is filled with people who proudly view themselves as patrons of the arts. Helping a needy artist is a noble act there. Even when Chet was at his frailest — especially when he was at his frailest — the Europeans were extremely touched by the pain he revealed so nakedly. Even if he had only tatters of his former technique, this outpouring of the soul touched everyone’s hearts. The Europeans loved him for it.

JJM The critic Martin Williams wrote of Baker in 1956, “The history of the performing arts in America is certainly strewn with highly promising, immature talents which are over-praised, exploited, and often, never fulfilled.” Did Baker’s use of heroin intensify as critics became harsher with his work?

JG Yes, although I wouldn’t swear it was a cause-and-effect situation. Chet got heavily strung out starting in 1956, around the time the critics had really started turning on him. He had just returned from a European tour that was far from triumphant. In fact it was marked by tragedy – the death, by heroin overdose, of his 24-year-old pianist Dick Twardzik, with whom Chet was, on some level, in love. It was becoming fashionable to knock Chet. He was falling in the polls, his records weren’t selling as well, and he had become yesterday’s pin-up boy. 1957 was pretty bad, 1958 was worse, and in 1959 he went to Rikers Island for four months. I think he had been dreading this fall for years, because in 1954, he had made it clear how pressured he felt by his success, how much he understood that he wasn’t really the world’s greatest trumpet player. By 1959, he was a mess, and that is when he fled for Europe.

JJM His world started falling apart in the mid-fifties when the critics started coming down on his work, which was simultaneous to the time Twardzik died of an overdose. There seems to be a variety of different stories about what really happened to cause Twardzik’s death and whether Baker may have been with him or abandoned him. You wonder if all these things had something to do with Baker blamed for Twardzik’s death. Not to suggest there was a conspiracy among the critics here, but Twardzik was a brilliant pianist and you wonder if they didn’t have some hatred toward Baker as a result of his addictions and how that led to Twardzik’s death.

JG Baker wasn’t a junkie yet when Dick died, although he had dabbled in heroin. To this day, most people have accepted Chet’s version of the death — namely, that Dick OD’d in his hotel Paris room, alone. But as I tried to show in my book, Chet’s many tellings of that story contain some red herrings. This happened again, even more dramatically, when Chet endured his legendary drug-related beating in San Francisco in 1966. Chet told and retold the story, and the details conflicted every time. Ruth Young, Chet’s girlfriend of ten years, was the first to suggest, in Let’s Get Lost, that maybe Chet had gotten his ass kicked for a reason. But I digress. To answer your question, when he came back to the States in 1956, he was tainted by the tragedy of Dick Twardzik; there was a lot of suspicion that Chet Baker was a junkie, and was somehow responsible for the death of this beautiful young man. Yet Twardzik had been a junkie since he was a teen ager, and obviously he was more reckless and self-destructive than even Chet. Dick was 24 when he died; Chet was 58.

JJM I think Twardzik’s death appeared to be a turning point in Baker’s career, as if it were a cause of him going from leading a life of “cool” to one of “despair.”

JG Yes, the European tour was supposed to be triumphant, and instead it was a big disappointment in a lot of ways. As soon as Chet Baker came back from Europe, he became a junkie.

JJM What were the circumstances of the San Francisco assault that caused Baker to lose his teeth?

JG In 1966, Chet Baker was really down and out, as Time magazine called it. He couldn’t work in the New York area because he didn’t have a cabaret card. He worked on the road as much as he could, but by 1966, work had really dwindled. He had a child from his second marriage to a young woman named Halema, but he wasn’t supporting that child in any way. He had a son, Dean, who was born on Christmas Day, 1962, and another son, Paul, born in 1965. Almost immediately after Paul’s birth, Chet’s wife Carol became pregnant with their third child together. Pressure! He had no money. He was strung out. He was offered a job at the Trident, a high-class night club in Sausalito where Carmen McRae and Bill Cosby and the Kingston Trio performed. Chet wasn’t the star; he was a guest of Joao Donato, the bossa nova pianist and composer who then lived in Los Angeles. Chet used to go to a sleazy hotel in the Fillmore district of San Francisco to score. It was a dangerous place for a white guy to be prancing around in at night. Chet swore, and almost everyone believed, that he was ganged up on by a group of thugs who wanted his dope money. But Ruth Young and a few of his friends were doubtful. Chet at that time was conniving drug prescriptions out of doctors, robbing homes, doing everything he could to get the drugs he needed, or enough money to buy them. Ruth suspected that he had over the wrong person, and indeed, Chet ended up revealing to Bob Mover, his saxophonist, that the beating was a payoff.

JJM Richard Carpenter, who is credited with writing a number of jazz standards, but didn’t write any of them…

JG Right, Richard Carpenter was the shyster manager who worked with Chet in 1964 and 1965, and who ripped off Chet and a lot of other strung-out musicians, unfortunately with their cooperation. The most famous song credited to Carpenter is “Walkin’,”, which was apparently written either by Miles Davis, Gene Ammons or Jimmy Mundy. Ammons and Mundy were clients of Carpenter’s.

JJM Carpenter stands as the person Baker hated the most in his life.

JG Chet wanted to kill him, literally. Carpenter is remembered as the greatest leech the jazz world has ever known. He started a career as a manager in the late forties. He and Johnny Hartman were boyhood friends in Chicago. Carpenter was an extremely obese black man, who looked like he would blow out anyone’s brains in a second. He preyed on down-and-out, drug-addicted black musicians, of which there were many. He presented himself as a big brother, a tough-guy protector figure who was going to ward off the whitey con artists who wanted to rip off the black guys. Carpenter didn’t have many white clients, but he signed Chet in 1964. Chet had just come back to America after having gotten bumped out of a number of European countries. Needing a place to stay, he had moved in with Tadd Dameron, the great arranger-composer. Dameron hooked up his manager, Richard Carpenter, with Chet, who needed any help he could get. Carpenter had gotten many of his clients to sign over their composer copyrights to him for a token fee. That meant that the royalties would go to Carpenter in perpetuity. Nasty. In exchange, he offered representation and work. Chet was desperate and needy enough to sign a contracts with Carpenter, and he got taken to the cleaners. In 1964, Chet still had his looks, and Carpenter felt there was still money to be made off him. There wasn’t, really. But we must give the devil his due. Through Carpenter, Chet recorded some wonderful albums, including Baby Breeze and Baker’s Holiday, both of them Carpenter productions. They didn’t sell. Chet was no longer a golden goose, and Carpenter lost interest in him fast. Baker railed against Carpenter for the rest of his life. But I think we need to acknowledge the fact that there were probably no royalties to be earned on these albums, that it wasn’t a complete case of victimization. Chet may have been in bad shape and quite vulnerable at the time he signed the contract, but he did sign it. I am in no way trying to minimize the horror of Richard Carpenter but let’s be realistic.

JJM You started writing this book in 1994?

JG Yes, I signed to do it in 1994 and I started researching it at the very end of that year.

JJM Carpenter died in 1996…

JG Yes, he was still alive at that time. I never did get to him, and I regret it. I didn’t really learn the Richard Carpenter story until sometime in 1995. I didn’t know where he was or how to get to him, and I think he would have been leery about doing an interview with me. I’ll never know.

JJM Baker’s death has been explored from so many different angles. You actually brought up something I hadn’t heard before, concerning the possibilities of hotel employees finding him dead of an overdose and then dumping his body out the window, which apparently was not unheard of. Baker certainly had suicidal tendencies, and by 1987 he had a growing preoccupation with death. The fact that he was a “second-story man” who was quite adept at scaling the sides of buildings makes me a little suspicious that he simply fell out a window. Isn’t it a likely scenario that his death was either a suicide or a fall caused by a delusion or hallucination?

JG After Baker died, people wanted to dramatize and romanticize his death as much as they had every part of his life. Given the three options — did he jump, did he fall, or was he pushed — which is the most dramatic? Murder! If you were making a movie of Chet Baker’s life, the most exciting ending would show him being murdered by a drug dealer whom he ripped off. I saw the entire police report, which was very detailed. It belies what a lot of people tried to suggest — that after he died, the investigation was shoddy, that the police didn’t care to look into how someone had offed poor Chettie. The fact of the matter is that Chet’s closest friends in the last months of his life do not believe he was murdered. The door to his room was locked from the inside, and there was no sign of a struggle. We also know that the window of his hotel room did not open high enough for someone to fall out, and if you wanted to get out, you needed to make a bit of effort. Chet’s spirit was broken at that time. His lover, Diane Vavra, whom he treated abusively but couldn’t live without, had fled for her life early in 1988. By April it finally hit him that she was not coming back. Her absence broke his spirit for good. For years, speedballs had been Chet’s drug of choice. That combination of heroin and cocaine is incredibly addictive. The high is staggeringly high, the crash intense, and Chet was also binging on amphetamines and hallucinating a lot. His last drug dealer told me that Chet was using six grams of heroin per fix. An average junkie uses about 1.5.

JJM It is terrifying and all so very sickening…

JG You said it! Chet had been showing signs of dementia in the last three years of his life. He had found a doctor in Amsterdam who was happy to supply him with all the amphetamines he wanted, and they made him go crazy, as Chet well knew. In his final week on earth, he binged on pure cocaine, which helped him go even farther out of his head. I view his death as a passive-aggressive suicide. He knew that if he were left alone and got as high as he did, that something bad was going to happen. He completely isolated himself in that hotel in the last hours of his life. Initially, nobody knew where he was. Nicola Stilo, his flutist and close companion, told meof having to restrain Baker from jumping out a window not very long before that. Baker would hallucinate heavily, and think there was somebody out there in a tree or on the street who was trying to get him. In his dementia, he thought he had to get out of the room.

JJM There is so much evidence pointing toward suicide.

JG How many times have we heard about people on LSD jumping out of windows because they thought they could fly? It surprises me that, in a lot of reviews of my book, people are still calling his death a mystery.

JJM Certainly a lot of people glorified Baker that are going to be real angry with you about this book, exposing him as an attempted murderer, an arsonist, a thief, all these things that serve to bring down Baker as their hero. You are going to get a lot of that stuff…

JG I’ve already gotten a lot of flak for that.

JJM In Norman Mailer’s 1957 essay called “The White Negro,” you point out how Mailer “glorified the American existentialist – the hipster, who understood America was headed for doom,” and whose response to that was, in Mailer’s words, “to live with death as immediate danger, to divorce oneself from society, to exist without roots, to set out on that uncharted journey with the rebellious imperatives of the self.” Could it be said this was Baker’s epitaph?

JG Absolutely! Except that I don’t think that Chet Baker had any grand, worldly scheme in mind. This was a man who, as far as I know, didn’t read the newspaper, didn’t watch the TV news, who only cared about getting what he needed. I don’t think he thought of himself as any kind of revolutionary; he just wanted to escape from pressure, from responsibility, maybe from his own anger. I think he wanted the love and approval of his father and never got it. I think he longed to escape the pressure his mother had put upon him from the day he was born — this perfect little angel child who was supposed to solve all her problems. Near the end of their relationship, Chet said to Ruth Young in a rage, “Don’t hang your life up on me!” A lot of people had hung their lives up on Chet Baker, and he couldn’t stand it. Why wouldn’t he have wanted to stay as high as he could? But let us not forget that, although Chet was called weak all his life, he was very strong, because how many people have survived such a life as long as he did? He made it to 58, which is a miracle. There are many times he should have died. I really dig the fact that he checked out only when he was ready to. He probably could have lasted a few years longer, but he decided it was time to bale. I wouldn’t call this weakness.

This whole story is terribly sad, but the fact that so many people are still fascinated by him is significant. People aren’t talking about Dizzy Gillespie in the same way, nor even about Charlie Parker. These were genius musicians, but they don’t have quite the air of mystery that draws people to Chet, like Pandora’s box. Brilliant as Dizzy was, there isn’t that much to debate there. Dizzy represented music, not any tremendous mystique or social resonance. It’s fun to talk about Chet and try to figure out the mystery.

JJM What is the last recording Chet Baker ever made?

JG The Last Great Concert is the last issued album, recording live in Germany on April 28, 1988. I guess the last song he recorded, commercially at least, is the one that ends that performance, “My Funny Valentine.” That night he played and sang a stunning nine-minute version of it with the strings, then repeated it as an encore. So “My Funny Valentine,” the tune that helped make him famous in 1952, became his swan song as well.

..

.

____

.

.

.

Deep in a Dream:

The Long Night of Chet Baker

by James Gavin

This interview took place on June 12, 2002, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician Editor/Publisher Joe Maita

.

.

______

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Chet Baker biographer Jeroen De Valk.

.

.

So insightful.. brings Chet’ s idiosyncracies, vulnerabilities into focus and the many sides to the man’s mystique and tragic life. It’ s also a fascinating prelude to his biography which l have just begun. It too is a deeply intimate account of a sadly neurotic but divinely gifted artist. A must-read for sure—