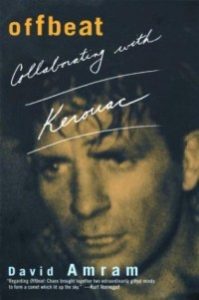

In this short excerpt from David Amram’s 2002 biography Offbeat: Collaborating with Kerouac, Kerouac talks with Amram about how the “Beatnik crap” that Kerouac and his friends reluctantly represented was “distorting everything,” and “cheapening the memories of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk.” It is an interesting and entertaining view of that era, filled with the vigor, passion, wit and wisdom Kerouac is remembered for.

_____

In January of 1959, we collaborated with a once-in-a-lifetime group of artists on the film Pull My Daisy. In addition to appearing in the film as Mezz McGillicudy, the deranged French horn player in the moth-eaten sweater, I composed the entire score for the film and wrote the music for the title song, “Pull My Daisy,” with lyrics by Jack [Kerouac], Neal Cassady, and Allen Ginsberg.

The idea of making a film based on Jack’s work was easier to talk about than to actually accomplish. May people felt that the experience of reading On the Road was like watching a film, projected on the screen of your mind, as you devoured the pages of his classic adventure story-poem-novel. All of his writing, like his spontaneous raps, conjured up kaleidoscopic imagery that made you feel that you were a member of the cast in a great documentary film about the quintessential America we all longed to be part of. Like most of the high-energy musicians, poets, painters, and assorted dreamers we hung out with, Jack relished every precious moment of each day and night. He often told me his books were sight and sound journeys, told in the style of a great jazz solo, to be shared by the readers, joining him on his endless odyssey.

One afternoon in the middle of November, 1958, Jack came over to my sixth floor walk-up apartment at 114 Christopher Street from his house on Gilbert Street in Northport. “I’ve got an idea for a short film, Davy, a petit flic about a simple afternoon at Neal’s house. It’s a scene from a play I’d like to write, about what we all mean to one another. Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky will play themselves. They are the psychotic poets who drive Neal’s wife and everyone else crazy. Larry Rivers is going to be Neal, and you can be Mezz McGillicuddy, the mad French-horn playing optimistic Irish-American nut-case. It will be a silent film, and I can narrate it after it’s been shot, whild you play the music for me, like a great Charlie Chaplin silent movie. We can do our part together spontaneously, like we’ve always done, while we’re watching the final edited version. We can paint a picture. No one today knows what Beat is about. They certainly have no idea what I’m about, especially if they read articles about me, where I’m misquoted. They’re forced to judge me by embittered journalists who gave up their dreams of writing to become slaves to heartless publications run by people who have never read a word I’ve written! They neglect the fact that I’m referring to the beatitudes, and to the beat of everyone’s ancestral drum that we carry through our lives, from the time we hear our mother’s heartbeat before we are even born. The Beatnik crap is distorting everything all of us are trying to say. It’s even distorting history by cheapening the memories of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk. In the forties when I heard them at Minton’s in Harlem, they were wearing berets and horn-rimmed glasses to show their allegiance with Picasso, Jean-Paul Sartre, and the revolutionary artists, because they wanted the same respect shown to them as American musical visionaries. The Beatnik craze has usurped their dress style, making a joke out of their struggles. The kids today are brainwashed about this. They don’t know that bongos are our link to Africa and have religious connotations. They don’t know about Afro-Cuban influences on American music, or Chano Pozo or Machito’s contributions to the history of jazz right here in New York City. They’re just kids, being guided by money-grubbing merchants, who no longer read books or sit in Bhodovista silence, digging the sounds of the last genius pioneers of bop. Allen accuses me of being stuck in the past. I tell him I only want to see this great chapter of history I witnessed recorded. What’s new comes from what’s old. And if it’s of lasting value, it stays new forever.

“Our little movie, notre petit flic, can hip-a-fy these kids to the ancient happenings of a few years ago. They can see all of us, now dismissed as passe pioneers of the Beat Generation as regular human beings and fellow artists, spending a silly afternoon together in a tete-a-tete, till Neal’s wife can’t stand our mooching and freeloading anymore and throws us all out of her apartment so that she, Neal, and the children can have a few family moments of tranquility. Ahh. Ca ne fait rien. Let’s go to Washington Square Park and see if we can meet a gum-chewing chess-master genius and invite some young gals up to your pad. You can cook them a Hector Berlioz-style omelet of leftovers with eggs, and I’ll recite them notes from y latest tome.”

Jack and I strolled over to the Park. Through the brisk November streets I told him about my new piece for string orchestra, Autobiography for Strings, which was going to be premiered in June of 1959 by Maurice Peress at a concert at New York University a few blocks away from where we were walking in the Village.

“It was inspired by what we have done together, combining the spontaneous and the formal,” I said. It’s a one-movement piece, using the sonata allegro form, with every note written out. I use a lot of jazz harmonies, walking bass lines, and ideas that I’ve made up on the spot as a player, ideas that are never used by composers in a string orchestra composition. It’s not elevator music or commercial shlock-shmaltz Broadway trash. I’m trying to create a piece of music based on the real thing, so orchestral string players can fell that spirit of what it was like for me to play with Mingus and Clifford Brown and Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, Dizzy, and Monk.”

“Stick to your guns, Davey,” said Jack. “Do it right and follow your heart. Otherwise the ghosts of Bartok, Gershwin, Schubert, and Charlie Parker will creep beneath your sheets like crawling cockroaches in the silence of the night and make you give penance and recite Hail Marys as they confront you in your petit chateau, sliding on the linoleum between mounds of pizza crusts and tortured socks.”

*

Excerpted from Offbeat: Collaborating with Kerouac

By

David Amram

Click here to read my 2002 interview with David Amram

Amram talks about the making of his film, Pull My Daisy

…am soooo glad I found your web site…met Amram through pal, Janine Santana, at “Dazzle”, a jazz joint in Denver. I’m a guitar-picker, trying to expand my horizons (it never ends) and just this one effort has helped. Looking forward to more. merci beaucoup[….Pierre Ardans

I constantly read Kerouac in high school. Never met him, but I did meet Allen Ginsberg at a party around 1970. Good times!