.

.

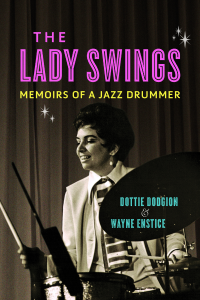

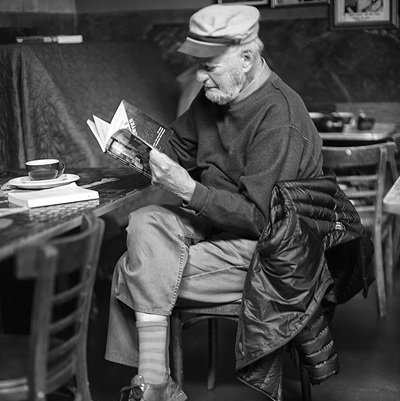

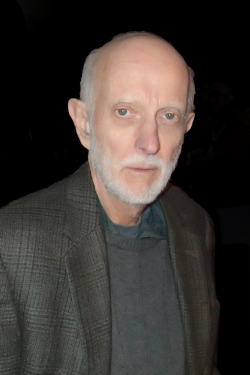

Wayne Enstice, co-author (with Dottie Dodgion) of The Lady Swings: Memoirs of a Jazz Drummer [University of Illinois Press]

.

.

_____

.

.

…..Every so often a biography of a jazz musician comes along and surprises even the most informed reader. Complex career stories are brought to light, troubling personal hardships are yielded to or overcome, and unfamiliar personalities emerge to impact one’s understanding of otherwise settled history.

…..One such book is The Lady Swings: Memoirs of a Jazz Drummer by Dottie Dodgion (who died in September, 2021) and her co-author Wayne Enstice, an enlightening, entertaining and rewarding read that reveals the little-known life story of the pioneering Ms. Dodgion, who defied the odds to become a world-class jazz drummer in a world – and on an instrument – dominated by men.

…..Ms. Dodgion writes that her success in this environment didn’t come easy. “The guys were not going to give it up – the drummer was the balls of the band – and I really had to prove it. When I first started playing, musicians would call the slowest ballad they could to show me up, to prove that a girl can’t swing at that tempo.” And she also had to overcome the blatant gender prejudice of the era that she writes “typecast me according to my looks and laid roadblocks in my path to becoming a professional jazz musician. Those roadblocks came in two flavors: blatant sexist behavior, or the more subtle ploy of invoking chauvinist cultural values that defined what was and was not dignified work for a woman.”

…..Her gifts weren’t confined to being a trailblazing cultural figure. Mr. Enstice writes that “comparable to [her cultural symbolism]…is her long-overlooked legacy as a player. How hard she swings, her artistry on the drums, and her rock-solid, in-the-pocket accompaniment. Beyond the centerpiece of her drumming is Dottie’s stature as a vocalist, including early performances that showcased her singing wordless melodies in jazz.”

…..Since she appeared on only a handful of recordings during her peak years, even informed jazz fans know little about the extent of her musical career or her relationships with those who comprised her inner circle. In an extensive interview with Jerry Jazz Musician Editor/Publisher Joe Maita, Enstice talks about his experience writing this book, and provides readers an understanding and meaning of Dottie Dodgion’s life and work.

.

.

___

.

.

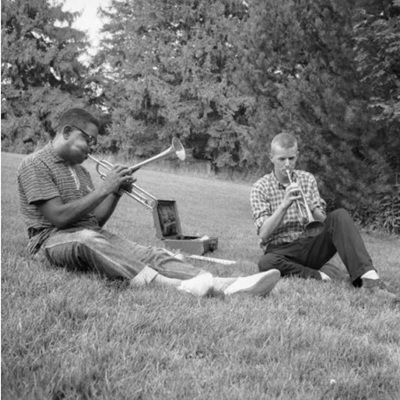

photo courtesy Dottie Dodgion

Bassist Steve Novosel, tenor saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, drummer Dottie Dodgion, and pianist Jimmy Rowles; Kennedy Center, Washington, DC, 1976

.

___

.

“Dottie Dodgion commanded first-call respect in the fiercely competitive, almost exclusively gendered New York jazz world of the 1960s and 1970s. She was one of a very few women of that era who assumed a mantle of pioneer by breaking into the circumscribed, hard-core male jazz fraternity on the drums, the most masculine of instruments.”

-Wayne Enstice

.

“As a female, I wasn’t expected to be strong or positive. One time a drummer in a club I was working stepped on the stand at the end of a tune and blustered, ‘Okay, I can take over now.’ I blustered right back: ‘Take over what? Get your own gig!'”

-Dottie Dodgion

.

.

Watch a mid-2010s video of Dottie Dodgion sing and play drums on “Deed I Do”

.

JJM How did you meet Dottie, and what was your process for determining whether to take this book project on?

WE Actually, the book started without me. I think it’s fair to say that the early stages of the process were prompted at least in part by two previous jazz books I co-authored. Jazz Spoken Here from 1992, written with Paul Rubin, is a collection of interviews that were originally broadcast from 1975-1982 on an NPR affiliate in Tucson. As fate, timing and demographics would have it, the musicians we met and ultimately featured were all men.

A few years after that book was published I developed a conscience about the absence of women in its pages. Janis Stockhouse, Director of Bands at a Bloomington, Indiana, high school, joined me as co-author of a book about female jazz musicians, with an emphasis on instrumentalists. We compiled a list of musicians, many of whom were important but little-known voices in the jazz world. Perhaps the most obscure figure among them was Dottie Dodgion. There was scant information about her but the mystery only intrigued us more, so with Dottie’s consent we arranged to meet her in 1997 at her home in California. A few weeks and several phone calls later the final edits to Dottie’s chapter were finished and our working relationship ended. Or so I thought.

Jazzwomen was published in 2004. Unbeknownst to me a California-based writer, Casey Silvey, read Dottie’s chapter and contacted her to propose a one-woman fictional play based loosely on episodes from Dottie’s life to pitch to various broadcast outlets. In 2008 Casey began recording a series of conversations with Dottie that eventually filled 24 audio cassettes. Dottie signed on with a look toward media coverage that could lift her out of obscurity; I also think she enjoyed the process of revisiting her backlog of colorful stories in the company of an avid listener. But one thing was certain: Dottie was adamant that she had no intention of using Casey’s project as a springboard to her autobiography. Two years later she changed her mind.

In 2010, more than a decade after Dottie and I had wrapped up her Jazzwomen interview, I was surprised to hear her voice on the phone. She called to tell me how the talks with Casey had inspired her to think seriously for the first time about writing her memoirs. Pleased with how Jazzwomen turned out, she decided to ask me if I would help with this new project. But I was hesitant to commit. Her coverage in Jazzwomen, like the other chapters in the book, was designed as an introduction, not a monograph. Plus my original research was anchored in the past, so for both reasons I felt flatfooted, unprepared to assess the full stature of her accomplishments and the social relevance of her life story.

To help me process the offer and tackle the question “Who is Dottie Dodgion?,” Casey sent me digital copies of the 24 taped conversations. The off-the-cuff content on those tapes multiplied my resources overnight. Glimpses of illuminating new material gave more shape to my subject and prompted me to take the next step: a return trip to California for a week of interviews with Dottie to fill in gaps and generally expand the substance and reach of her stories.

Once new material was plugged in, I prepared my first working outline and began contacting musicians Dottie had worked with to learn first-hand how she was regarded by her peers in the jazz world. I did 40 interviews and was fortunate to reach several important figures in Dottie’s life before they passed (eg., Iola Brubeck, Frank Wess, Grady Tate, Bob Cranshaw, Bob Dorough, John Coates, Jr., Phil Woods, Marian McPartland). Perhaps most crucial among them were exhaustive sessions with the late bassist Eugene Wright, a member of the iconic Dave Brubeck Quartet and Dottie’s beloved mentor.

It took a few years but once the puzzle pieces snapped into place Dottie and I felt for the first time that maybe we had a book.

JJM Dottie Dodgion is a virtual unknown among fans of music. What does the jazz world of today know and remember about her?

WE First and foremost that she was a swinging drummer. Second, that between 1961 and the mid-1970s she was consistently blazing a trail for her gender by playing a “masculine instrument” in otherwise all male, world-class east-coast jazz bands. Third is her resume as a vocalist, from her delivery of wordless vocals in the mid-1940s to her late-career maturity as a storyteller.

Dottie was part of a special circle of jazz musicians, an “old-school clique” on the East Coast and particularly in New York, who embodied the swing-to-bop tradition that is often referred to as “mainstream.” Among others, that group included Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Bob Cranshaw, Phil Woods, Al Grey, Joe Venuti, Milt Hinton, Hank Jones, Louie Bellson and Ruby Braff. Bassist Cranshaw remembered Dottie’s great pocket and how the two of them in a rhythm section laid down a firm floor for the frontline to be able to play.

Musicians knew what they were getting when they hired her, a quality that Eugene Wright and her eventual husband, the altoist Jerry Dodgion, noticed from the very beginning: a gift for infectious swing. Even in the 1960s when jazz was going through fundamental changes that included the freeing of drummers from conventional timekeeping, Dottie remained steadfast both in her conception and in her compact with colleagues who held the mainstream-jazz tradition dear.

Dottie was proud that she never asked anyone to let her play; she was always invited. And not because she was a novelty but because of her qualifications as a drummer. As Richie Cole put it, Dottie “was one of the guys.…It wasn’t like there was a woman on the outside trying to get in; she was already in.” Nevertheless, even at the height of Dottie’s career her potential as a recording artist was overlooked. And although she was a natural with audiences and had the savvy to be a strong leader, she typically was hired as a side person. But over time word got around, and so despite chronic neglect by the industry she earned an underground reputation as an original among women drummers who succeeded her.

JJM Her early childhood was interesting on many different levels, especially her relationship with her father, a drummer who Dottie described as having “kidnapped” her from her mother at age five, subsequently traveling with him and his band across the country until she was seven …

WE I would use the word “checkered” to describe their relationship. She loved her father dearly and had tremendous respect for him, but despite his absenteeism her father exerted heavy-handed control in Dottie’s formative years that she came to resent. When he kidnapped Dottie she got her first taste of life on the road. Her father played a circuit of roadhouses and Dottie would wait for him in a locked room while he played a gig one floor below. Occasionally when she’d sneak down the stairs to watch her father and listen to his band one of the dancers would sit her on top of a piano to sing some ditty like “Three Little Fishes.”

Dottie’s father never gave her a formal music lesson so whatever insights she picked up on that score were absorbed unconsciously. Nevertheless, she was fascinated by him. Watching him smile and sing while playing the drums made her believe as a youngster that all drummers could do that. Of course that wasn’t the case, her father was special in that way, but when in her later years she yearned for a return to melody in her work, she adopted that model. When she was financially strapped it also helped that singing while playing the drums commanded a bigger paycheck.

Her father’s lifestyle was fastidious and carefully organized. Interruptions, like a day job, weren’t tolerated because the music always came first with him. Any distraction, including women, would inevitably take a back seat. That was also true of Dottie’s first husband, Monty Budwig, who considered himself a bassist first, a human being second. The mature Dottie was cut from the same single-minded cloth. Her constant preoccupations were the drums, her rhythm-section fit and the overall sound of the bands she cooked. Dottie’s affection for her instrument was no secret; later in her career, as a variation on “boy loves girl” songs, she would sing the old Harry Warren/Mack Gordon chestnut “This Is Always” as a paean to her drums. Like her father, she refused to sellout taking a day job or playing music that was blatantly commercial.

JJM What kind of economic situation did she grow up in?

WE Her family was Appalachian working class. Her mother grew up in the hills of Tennessee, and her grandfather, who worked cabooses, was full-blooded Cherokee. When her drummer father abandoned them, her mother had to scuffle to make it; the desperation only increased after her mother’s brutal second marriage and divorce.

JJM This was after Dottie’s stepfather raped her when she was a little girl…

WE Yes, she was raped at 10. Her mother worked at Woolworth’s and her stepfather was a steam fitter. Then he got laid-off and began to drink their income. The shock of the rape devastated Dottie and her mother, emotionally and financially. After the trial they survived for a time on a diet of zucchini cooked every way imaginable. Their economic plight persisted for several years until Dottie’s mother married a marine by the name of Sammy Sampson who came from a wealthy Boston family. He was the love of her life but they had only one year together before he was killed at Guadalcanal.

Dottie endured dizzying financial ups-and-downs throughout her life, including times when making the rent rode on her split of the tips after a gig. Bleakest was her Fort Greene period in the early 1980s when she was homeless and living perilously on the edge of poverty.

JJM What made Dottie think that she could succeed musically?

WE I don’t think it was a cognitive decision. She had a bent toward music as a child that grew into an undeniable passion as she matured. In that sense, music chose her. And it can’t be overstated that the importance of music for her as a youngster was heightened by the escape it afforded from the horror of her home life. In that sense, she had no choice.

Early on her musical focus was dancing. Dottie was the jitterbug queen in her high school and she took lessons for a year with a dancer friend of her father’s named Hoppy, who was impressed with her time and how her “big ears” enabled her to quickly learn complex rhythmic patterns and anticipate their resolution. After she won first prize in a dance contest at the 1939 World’s Fair she looked toward a career in ballrooms, chorus lines and clubs but her father discouraged those ambitions—he called dancers “gypsies,” and said there was no money in it. Instead he encouraged her to sing.

Her bodily intelligence, her keen motor skills honed by dancing, was also expressed in sports as she excelled on the basketball court in grammar school and on the mound for her high school softball team. So Dottie got confirmation and indeed recognized on her own that she possessed a gift so very fundamental to her love of music: an innate feel for rhythm.

JJM Before she was a drummer, Dottie was a singer, and in the book you write about how she incorporated drumming and singing while she played with the Mary Kaye Trio, a popular lounge act at the time. How would you describe her early singing style?

WE As a young adult Dottie was focused on singing; drumming was not on her radar, so the incident in 1949 you refer to was an anomaly. Stranded in Omaha by an unscrupulous comedian she was rescued by the Mary Kaye Trio and schooled by them on a standing tom. She quickly mastered a standard swing rhythm and performed with the group singing and improvising on that basic drum pattern as they trekked west playing gigs back home to California.

Dottie’s early singing style was inspired by the great time of Anita O’Day—“she was like a tap dancer to me”—and the clipped phrasing of Fred Astaire. Like Astaire, Dottie didn’t have the chops to hold long notes so she concentrated on phrasing to convey the lyric, a storytelling approach that flowered in the 1990s as her style matured and she started using a boom mic to free up her hands for more expressive drum accompaniment. In the mid-to-late 1940s her ability to memorize complex charts (she couldn’t read) was in ample evidence when she sang “phonetics” or wordless vocals in the Nick Esposito sextet. Her work in this idiom was contemporary with similar explorations by the duo of Jackie Cain and Roy Krall.

Since there was a dearth of recorded examples of Dottie either at the drums or doing vocals, I set the goal early on to see if lost or previously unknown recordings existed and might be available. I’m pleased to say that via a circuitous route that led to a collector in Germany I located the original and very rare 1949, four-star recordings Dottie made singing phonetics with Esposito, who was a well-respected San Francisco bandleader at the time. I also gained access to a private unreleased dub of Dottie in 1962 doing a vocal and playing drums in a group that included pianist Chick Corea, altoist Jerry Dodgion and the “Senator,” bassist Eugene Wright. Another break led me to the live set performed in 1978 by the Festival All-Stars at the first Women’s Jazz Festival in Kansas City. These formerly unknown recordings were hiding in plain sight at The Library of Congress in Washington, DC. (Selections from each of these performances are available for streaming at the press website with the purchase of a book.)

JJM She tells many great stories in the book, one of which took place in 1947 and involved her singing with Charles Mingus at a biker bar called the Knotty Pine on San Pablo Boulevard in Oakland. What was the experience of working with Mingus like for her?

WE Dottie thought very highly of Mingus and it’s telling how down she felt after he disbanded the group and left Oakland. Mingus hired her in 1947, for what might be described as one of his early workshops, after hearing her sing phonetics with Nick Esposito. He felt Dottie could help him realize his own approach to integrating vocalise with instrumental arrangements. She became, as Dottie put it, “one of his inventions.”

The band rehearsed five hours a day three days a week for months waiting for a gig. As a bandleader Dottie described Mingus as alternately sweet natured and intimidating, a perfectionist who had everything worked out and imposed a stern work ethic. There was no “chit-chatting” when they rehearsed. Mingus wouldn’t write anything out for Dottie because she couldn’t read music, but by the time the rest of the band had a chart down she would have it fully memorized. Dottie recalled how Mingus’s face lit up with a grin when all that work paid off and his bowing blended seamlessly with Dottie’s vocalise.

The extended gig at The Knotty Pine occurred over the Christmas holidays in 1948. New Year’s Eve was particularly memorable. During that set Mingus grew increasingly dissatisfied with his distracted drummer, Kenny McDonald, who kept messing with the time. Mingus warned him to “quit looking at the bitches and concentrate or I’m going to throw you off the stand.” And that’s just what happened. His patience finally gone, Charles took McDonald by the lapels and threw him down a flight of stairs behind the drum chair. Dottie feared for the drummer’s life, but he survived and Mingus hurried to replace him.

Mingus had no clue that Dottie played drums until years later when he went to the Half Note in New York City and found her playing with Zoot Sims. After a pronounced double take he climbed on the stand and jammed beside her. During that same period, Mingus formed a large ensemble and Dottie recalled seeing his charts. They caught her eye because instead of notes Mingus used pictures (eg., a house, a stream) as source material for his band to interpret. The band sounded, according to Dottie’s affectionate description, as if Mingus had opened the proverbial “McGee’s Closet” [a reference to the popular comedy radio show Fibber McGee and Molly].

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Dottie Dodgion sing and play drums on “He’s Funny That Way”

.

JJM Dottie called Eugene Wright “the most important teacher I ever had.” Talk a little about their relationship?

WE Dottie first heard Eugene in 1955 when he was with Buddy DeFranco’s quartet playing a week-long gig in the Bay area. The swing that DeFranco’s rhythm section generated, and in particular Eugene’s deep bluesy “ging-gang” bass, thrilled Dottie and convinced her once-and-for-all to commit to playing the drums. During the intermission that first evening she felt compelled to introduce herself to this virtuoso who made her jaw drop in amazement. My impression from Eugene is that her sincerity in turn impressed him, creating an immediate bond between them.

She went to every performance and between and after sets they’d talk music and agree to get together to jam at the first opportunity. A few months later Eugene called; he was back in town and wanted to play the blues. That first weekend at the Dodgion’s home in Larkspur, CA set in motion a six-year tradition of private jams, the music interspersed with Eugene’s sage mentoring and fortified by the special Italian sauces that dressed Dottie’s home cooking.

Eugene quickly recognized and began building on Dottie’s potential; she was rough cut but swinging and playing good time. My conversations with each of them about Eugene’s lessons gave me rare access to the secrets of Dottie’s coming-of-age as a musician, the inside story of how Eugene Wright passed the generational torch to her. As Eugene said, “She’s my baby. I raised her, Dottie Dodgion.”

JJM And Eugene told her to not let anyone talk her out of playing the drums, to not merely settle for being a singer, which was the traditional place for a woman in a jazz band…

WE That’s right. Eugene wanted her to be confident about her ability, never to doubt that she was a qualified drummer who had a feeling in her playing that a lot of drummers didn’t have. He emphasized that she could play with anybody. Eugene taught her about supportive playing in a rhythm section, bandstand leadership, and industry politics. She was a complete professional by the time she moved to New York.

JJM Who were some of her favorite drummers who may have impacted her vision for and experience with the drums?

WE Kenny Clarke was at the top of her list. Dottie was impressed by Clarke’s sensitivity to the total sound of his bands, something that Eugene stressed in his teaching. She took great pleasure learning that Clarke was a listening musician who shared that ethos. Clarke’s ability to effortlessly shift from playing with a small group to driving a large ensemble also inspired her. When Dottie was coming up, she wasn’t aware of many drummers who could work equally well in both settings. Another influence was the crisp swing of Papa Jo Jones on the brushes.

JJM One of the stories she tells in the book is of an experience she had playing with Benny Goodman in 1961…

WE That story begins in March of that year when Dottie went to see her husband Jerry finish up a gig with Goodman at Lake Tahoe. While the stagehands were clearing the equipment, some of the musicians wanted to ease down from the evening with a jam but there wasn’t a drummer in sight. Then one of the guys spotted Dottie and invited her to get behind the drums. After a few numbers Benny heard the groove and couldn’t resist getting a piece of it. He set off a furious tempo on the next tune and they had a ball, chorus after chorus. That was the first time Benny heard Dottie play and, as things turned out, it was an auspicious sendoff for her flight the next morning to New York City.

Goodman’s band left on the same plane for a two-week engagement at Basin Street East and Dottie tagged along with Jerry for her first trip to the Big Apple. That afternoon, after dropping Jerry at the rehearsal, Dottie went shopping for a raincoat on Fifth Avenue. She returned to collect him just as the rehearsal was ending so she was surprised when Benny told her to get up on the stand. Then the memory of Tahoe the night before kicked in and she figured he wanted to jam some more. She didn’t know that Benny had been looking for a new drummer and that he was auditioning her for the job. Benny called several numbers with both his sextet and his ten-piece band and she played them flawlessly– she knew all the intricacies of those charts from the late-night listening sessions with her dad. Benny hired her on the spot to start that evening at Basin Street—her first day in New York! As Dottie put it later, she “answered his ad.”

JJM Apparently Goodman felt Dottie upstaged him at some point during the Basin Street East engagement?

WE Customarily, Benny would announce band members at the end of each performance, but during his wrap-up one night about ten days into the engagement he overlooked Dottie, who sat conspicuously on the drum throne. The band had just finished “Sing, Sing, Sing,” a song on which she was the featured soloist, and so the audience was vocal about his oversight. “The drummer! The drummer!” they yelled. Benny, chagrined, muttered out, “Oh yeah, Dottie Dodgion,” an awkward moment that was followed by a standing ovation for her that brought down the house. As she left the stage and passed the band manager he whispered “Bye,” in her ear and Dottie knew immediately that she was in trouble—nobody got a bigger hand than Benny— and sure enough, she was fired the next day. A few days later she received roses and a consoling note from none other than drum legend Gene Krupa that read; “Just remember, Baby. He’s fired the best!”

JJM That’s a great story, and there are others throughout the book, including one with the trumpeter Ruby Braff, a notoriously challenging bandleader who was attracted to Dottie when she toured with him, and who hoped for a romantic relationship with her even though she was married at the time.

WE That is a very poignant episode in Dottie’s life. Winning the drum chair in Ruby Braff’s quartet was one of the triumphs in Dottie’s career. Braff was a celebrated soloist and she joined pianist Hank Jones and bassist Milt Hinton to complete one of the premiere small-group rhythm-sections of that era. Early in their association, Ruby went so far as to declare that with Dottie he had found his drummer, he would never have to look for another. Sadly, that ride on a high note was short-lived, eclipsed by extra-musical and all-too-human foibles.

Dottie had great respect for Ruby on the bandstand; off the bandstand he was incorrigible. His brutal honesty could make her wince, but even more upsetting was Ruby’s escalating interest in Dottie as a woman. She stressed that Ruby was an honorable man who never made explicit advances toward her. However, at times there were intimations—for example Ruby’s suggestion that she move to England with him for tax purposes—that were not so subtle attempts to insinuate himself between her and Jerry.

After eighteen months, Dottie’s futile attempts to manage Ruby’s uncompromising nature, to cool his ardor toward her, and to contain the mounting tensions between Jerry and him, chilled their relationship and primed her exit.

JJM Dottie’s life was interesting on many levels beyond music. A few examples; she needed help with her daughter Deborah at an early age so she had her parents raise her for a time; her marriage to Jerry was an “open” relationship; early on in life she got pregnant by a man she didn’t want to have a child with so she gave herself an abortion; and her first husband Monty Budwig played bass with Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan and Russ Freeman at a time when they were strung out on drugs, and Budwig was also using. So she led a very complex, challenging life that must have been a fascinating experience for you to take in as her biographer…

WE Not just for me. More than one person has said that they fell in love with Dottie after reading her book. I think that’s a visceral response to her courage, an admiration for her defiant resolve to keep her ambitions intact often against formidable odds. The steps she took could be messy and she made decisions that make us cringe but her imperfections were part of her charm and she emerged a soiled but authentic heroine.

Dottie’s life during at least her first five decades was marked by bouts of debilitating illness (polio; burst appendix; abdominal adhesions) that twice left her at death’s door. That same period also found her burdened with frequently tough, at times irreconcilable choices. Dancer or singer? Show business headliner or crop-duster’s wife? Bad boys or men of quiet determination? But the most dramatic moral dilemmas Dottie faced arose from conflicts between two irresistible drives for meaning: a pull to motherhood and the freedom to pursue her identity through a career. Dottie’s struggle with those opposing forces resulted in two harrowing abortions and the agonizing decision to relinquish her infant daughter for what turned out to be sixteen years, leaving her prey to enduring spasms of guilt.

By nature Dottie Dodgion was volatile and she could be intimidating. Get her angry and be prepared for a one-liner designed to weaken you at the knees. Dottie’s benevolent side was equally disarming, inspiring in friends old-or -new a remarkable devotion. I watched members of her audience flock to her one night after a performance in a California lounge. I think they could sense the pain under the smile that wrapped around them. Her complex, challenging life made her a genuinely sympathetic figure.

JJM On first glance readers may think that the most compelling part of her biography is that she was a female playing a masculine instrument in a virtually all-male world, and that is certainly one. But there is so much more to her story — the challenges of her childhood and of raising her own child, her complex relationship with her mother and step-father who basically raised her daughter, working in an environment where drugs were prevalent and consumed by people she loved. So, you uncovered a fascinating and complex life…

WE Yes, but in spite of all the emotional turmoil, she had the discipline to find her voice and make creative contributions in the arts. Just pursuing her ambitions was no small task. It was as if she felt her way along a steep learning curve professionally and personally, from one new experience to another— going back and forth from darkness to light—that would create either opportunity or wreak havoc in her life. Imagine the horror of performing an abortion on herself on a bathroom floor, or discovering that her eleven-year old daughter was tripping acid with instruction from Timothy Leary, then add the exhilaration of joining Benny Goodman’s rhythm section her first day in New York. It’s exhausting to contemplate living a life like that.

JJM Dottie just passed away in September of this year. How did she spend the final twenty-or-so years of her life?

WE After leaving Melba Liston’s band in 1981 Dottie landed a coveted gig at the historic Deer Head Inn in the Delaware Water Gap. She was hired as the permanent house drummer in a trio led by another unsung figure, pianist John Coates Jr. She would have been happy finishing out her career at the Deer Head but when Coates’ health declined and he disbanded the trio she found herself at loose ends professionally. Then life threw another curve.

Her stepdad died in 1985 and since Dottie and her daughter were the only heirs (her mother died three years earlier) Dottie had to fly to California for her Mom’s will to be probated. Expecting a quick turnaround, she was disappointed when a full court calendar stalled her departure. She moved into her Mom’s trailer in Monterey and after a few months began to enjoy her independent lifestyle. For the first time she didn’t have family members or a bandleader making demands on her; she could devote herself entirely to herself.

In a holding pattern, she took stock of her options and faced another tough choice: return to the east coast or stay in California? It would be hard to give up the big-city fast lane but she also knew that a woman drummer in her mid-fifties would not be a hot commodity in New York, and, on top of that, the prestige of her prized Big-Apple jazz scene was in serious decline with the ascendancy of rock music. So, what was she going to miss? Snow? Seedy urban neighborhoods? At her stage of life, she found that the simplicity of California, the sunshine and pared-down wardrobe, calmed her. The more she thought it over the less she wanted to go back. Fate seemed to sympathize since the probate process continued for two years, giving her more than enough time to test and stake out her future in California.

To find work she renewed her California contacts and struck gold in 1987 when bassist Buddy Jones told her that a top-flight west coast band, the Jackie Coon Quartet, needed a drummer. Shortly after beginning a two-decade association with leader Coon on flugelhorn, guitarist Eddie Erickson and bassist Jones, the tears she had shed over Hank Jones and Milt Hinton evaporated. In 1991 the renewal of her west-coast stature was given a boost when she was hired as the regular drummer for Papa Jake and His Abalone Stompers, a band of late 1930’s vintage that had opened the first Monterey Jazz Festival in 1958.

In 1994 her first recording as a leader, Dottie Dodgion Sings (Arbors Records), rekindled her presence as a vocalist and spearheaded a series of independently produced late-career recordings over the next twenty years that swelled her discography. The last fourteen years of her life The Dottie Dodgion Trio was installed every Thursday night at The Inn at Spanish Bay in Pebble Beach.

JJM I actually remember seeing her play in the lounge years ago while my family and I were having dinner at the resort…

WE She originally got that gig when noted Brazilian drummer, Helcio Paschoal Milito, left after playing there for twenty years. Helcio had been working Thursday through Sunday accompanied by piano and guitar. Dottie went in to hear him one night when he was playing steel drums. Helcio, knowing her reputation, asked “You want to try these drums?” Dottie gave it a go even though she’d never played them before. Using mallets on the steel pans, she had a ball and Helcio was very impressed.

Months later Helcio contacted Dottie. He had grown tired of playing Thursdays, by far the slowest night at the time, so he gave that night to Dottie’s trio. Not long after, in mid-winter, 2007, Helcio left the west coast permanently for New York and the owners of Spanish Bay offered Dottie the four-day gig. She declined because of the toll it would have taken on her physically, opting instead to just keep her Thursdays.

Early in 2020 Dottie shattered her shoulder in a fall. Incapable any longer of playing the drums, she continued to perform singing stand-up at the mic, backed by her trio, until the coronavirus pandemic cancelled the gig for good in March, 2020. In December, 2020, Dottie suffered a massive stroke that hospitalized her for the rest of her life. The Lady Swings; Memoirs of A Jazz Drummer, the fruit of our ten-year collaboration, was published by the University of Illinois Press at the end of March, 2021.

On September 17, 2021, just six days shy or her ninety-second birthday, Dottie succumbed to complications from the stroke. Her daughter Deborah told me that towards the end of her life, Dottie, in a heavily medicated state, told her that she had seen Miles Davis sitting on the edge of her bed and he said, “Your book is going to be a huge success!” I thought that was a lovely coda for her life.

JJM What is Dottie Dodgion’s legacy?

WE First of all, her description as a vibrant role model. Dottie’s reputation as a survivor who persevered to become a pioneer on her instrument has served to inspire succeeding generations of women drummers. Second is Dottie’s dedication through the pages of her memoir to pay forward the lessons she learned that served as building blocks for her own conception as a jazz musician. Correspondingly, as her recordings are studied and others possibly discovered, the scope of her musicianship, including her personal voice as a swing drummer, will add other dimensions to her gift.

.

___

.

photo courtesy Dottie Dodgion

Dottie Dodgion, Basin Street East, NYC., March, 1961

.

“There is not necessarily a feminine aesthetic to her playing anymore than there is from good male drummers, which is why she was considered a first in breaking through the gender barrier of the instrument…I completely recognize that I stand on her shoulders, as [do] all the younger women that came after me…whether they know it or not.”

-Terri Lynn Carrington

.

.

Watch an early 2010’s video of Dottie Dodgion performing “This is Always”

.

.

___

.

.

The Lady Swings: Memoirs of a Jazz Drummer

[University of Illinois Press]

by Dottie Dodgion and Wayne Enstice

.

.

Praise for the book

.

“A pioneering woman in jazz and swinging drummer, Dottie Dodgion played with some of the great musicians of her time. She has a unique story to tell.”

-Quincy Jones

.

“When I first caught Dottie Dodgion in action I was bowled over. I didn’t hear a great female drummer but a truly great jazz drummer, period, able, as you’ll be happy to learn from the story she tells with such insight, humor, and complete honesty, to please both Charles Mingus and Wild Bill Davison. The lady’s words swing as hard as her ride cymbal, and will keep your foot tapping all the way through.”

-Dan Morgenstern, Director Emeritus, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

.

“Dottie Dodgion not only takes you on a dizzying ride through her incredible life, she teaches you some of the great secrets of jazz and unmasks the archaic attitudes toward female musicians that have marginalized great talents like hers. What a wonderful journey she’s had. What a wonderful book this is!”

-Judy Chaikin, director and cowriter of The Girls in the Band

.

.

___

.

.

Wayne Enstice is co-author of Jazzwomen: Conversations with Twenty-One Musicians and Jazz Spoken Here: Conversations with Twenty-Two Musicians

.

.

Listen to a 1977 recording of pianist Marian McPartland, guitarist Mary Osborne, saxophonist Vi Redd, bassist Lynn Milano and drummer Dottie Dodgion perform “In a Mellow Tone”

.

.

_____

.

.

This interview took place on October 27, 2021, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician Editor/Publisher Joe Maita. Thanks to the author and University of Illinois Press for allowing use of several of the photographs found within the interview

.

.

.