.

.

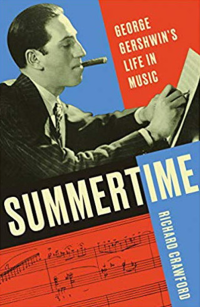

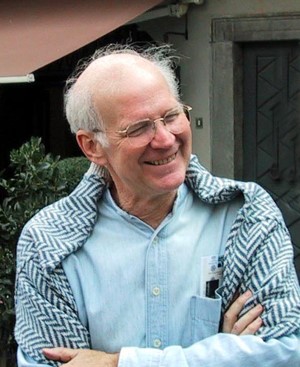

Richard Crawford, author of Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music

.

___

.

…..In the introduction to his book, Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music, the renowned American musicologist Richard Crawford writes that Gershwin began his career as a “fresh voice of the Jazz Age” who “maintained the flavor and conviction of that voice through the better part of two decades.”

…..Only two decades, of course, because a brain tumor cut Gershwin’s life short in 1937 at the age of 38. Had he lived longer, imagine what he may have written, and who could have performed his music. Additional Gershwin compositions would have had to enlarge the breadth of the Great American Songbook, as well as influence the worlds of opera and classical music.

…..But in Summertime, Crawford doesn’t concern himself with speculation, or to look at the post-Gershwin world. “Thanks to the efforts of [two dozen Gershwin biographers],” he writes, “Gershwin’s achievements are well known today. Most of all, the verve and panache of his music has won a place for it in the world’s soundscape.”

…..Instead, Crawford felt justification for a new Gershwin biography, now eighty-eight years after his death, that is “an academic scholar’s account of Gershwin’s life in music during the composer’s own time.”

…..The resulting work – which the author began in 2003 – is a rich, detailed and rewarding musical biography that describes Gershwin’s work throughout every stage of his career, including his Tin Pan Alley beginnings; his popular music success as a Broadway songwriter; his composition of Rhapsody in Blue that became a pillar of the Jazz Age, and vaulted Gershwin’s subsequent journey into the world of classical music and Hollywood, culminating in the daring undertaking of Porgy and Bess, a multi-cultural spectacle that is now one of the world’s great operas.

…..It was a great privilege to have discussed many of these topics with the esteemed (and now 84-years-young) Richard Crawford, who takes up the life and music of Gershwin, a man he has described as an artist who “challenged Americans to rethink their assumptions about composition and performance, nationalism, cultural hierarchy, and the racial divide.”

.

.

___

.

.

This interview was conducted by phone and email during the week of February 6, 2020, and hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection

George Gershwin, 1937

.

“George Gershwin, born in New York in 1898, belonged to that generation: a composer whose command of the realm of melody, success in popular songwriting, assimilation of a jazz-based idiom from black pianistic colleagues, and passion for learning about his art enabled him to stand apart from his contemporaries. Bringing to his work a compositional voice appealing to listeners on both sides of the purported classical/popular divide, Gershwin was a unique figure on the American scene”

-Richard Crawford

.

.

Listen to a 1937 recording of Billie Holiday sing George Gershwin’s 1937 composition, “You Can’t Take That Away From Me”

.

.

___

.

.

JJM.You describe yourself as a “musicological Americanist.” Can you explain what that is?

RC.When I passed my academic program’s test in the field of musicology, as a family man with offspring by then, I chose to stay in Ann Arbor to work on material held by a library on the University of Michigan campus that specialized in early Americana. The field of musicology, my discipline, is grounded in the study of European music making, beginning in the medieval era. But I discovered in Michigan’s Clements Library a collection of materials worthy of a Ph.D. dissertation: the papers of a New England musician, Andrew Law.(1749-1821) – a pious Protestant who taught singing schools from Connecticut to South Carolina. The Clements holdings preserved hundreds of letters to and from Law, and dozens of tunebooks that he had compiled and published as he taught the art of singing Protestant hymns and anthems. By the time I completed a Ph.D. thesis on Law and his work, which soon appeared in book form, I knew that the realm of his life and music-making were worthy of more investigation.

I was invited to join the University of Michigan’s School of Music faculty, where I taught courses on a broad variety of European and American musical traditions for four decades. And by the time I retired from the classroom in 2003, I had completed and published, among other books and studies, a history of music making in this country, America’s Musical Life: A History, from beginnings to the dawn of the twenty-first century.

As a scholar specializing in American music—a rare calling in the 1960s and 70s – I found my view of these beginnings changing as time went by..Investigating and writing about what I was learning, I found myself following Andrew Law involved in a British musical repertory that between 1770 and 1820 was evolving into an Anglo-American repertory, as the presence of music by home-grown composers increased in the tunebooks. And because much of the American music from those years was simple enough for the students to play and sing, we did quite a bit of those in my American music classes.

JJM.Did you enjoy popular music?

RC.My high school years had revolved around jazz music, so I was caught early in life by that music, and my American music course always devoted three weeks to that tradition. I didn’t pay much heed to rock and roll because that realm’s emphasis on the look-at-me display of performers turned me off from the get-go. Over the years my own offspring and students in my classes have helped me appreciate some music in that sphere, but its idiom and attitude have rarely caught my ear.

JJM.You wrote, “Gershwin was a unique figure on the American scene. But as the teacher of a one-semester course on America’s music, I was slow to perceive him as a major figure in that history.” Why?

RC.Well, folks of my ilk, having grown up in a jazz tradition dominated by African American artists, and also having studied academically the excellence and power available in music’s classical sphere, had reason to hear a masterpiece like Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue—a thunderbolt on American concert-goers’ scene – as a watered-down version of the real improvised music-making. Now, though, I‘ve come to appreciate the Rhapsody as a miracle.

JJM.When did you start writing this book?

RC.When I retired from teaching in 2003.

JJM.In the book’s introduction, you wrote, “Thanks in part to [Gershwin’s biographers], Gershwin’s achievements are well known today.” Given all the biographies and information already known about him, what made you decide to write a biography on Gershwin?

RC.I decided to write a biography of Gershwin in his own day, and not go beyond what was known of him while he was alive. Many biographies have reported data about Gershwin and his music after he died. But this one sticks to the man in his own time.

JJM.In a recent review of your book by Geoffrey O’Brien for the New York Review of Books, he wrote, “In its five hundred pages, we learn in rich detail about his musical development, but relatively little about his emotional side, beyond the gathering impression that the calendar of his hyperactive life masks a central unknowable solitariness.” Was discovering and revealing his emotional side at all a goal of your book?

RC.By the time I had completed a chronology of his life and work, the richness of the documents I’d found had presented such a clear and compelling record of his achievements, and of his relationships with other people. I judged that a description of these realms and their context would stand in for any authorial cheering from the sidelines. Moreover, I figured that the presence of Ira Gershwin would give the reader an intriguing window on the emotional flavor of his brother’s life and their work together. So, I’m OK with my treatment of his “emotional side.”

JJM.He had challenges early on. For example, he was once humiliated by a comedian, who, after hearing him play told Gershwin, “Who told you you were a piano player? You ought to be driving a truck.” He took it hard and told the box office cashier that he was “quitting,” and left without picking up his $3.15 pay. You wrote that “to fail on musical grounds wounded him unforgettably.” What options other than music did Gershwin have?

RC.The humiliation he suffered in this incident at the start of his career as an accompanist seems never have been repeated. Once he went to work at age 15 as a song seller, there’s no evidence that – with the help of the parade of teachers he hired and consulted through the rest of his life – he had more reason to doubt seriously his capacity to tackle any musical challenge he accepted.

James P. Johnson, c. 1946

JJM.Gershwin was drawn to music made by African-Americans, and had contact with three illustrious musicians before 1920, Eubie Blake, Luckey Roberts, and James P. Johnson, who were professional “ticklers” who played in, you wrote, “saloons, cabarets, dance halls, ballrooms, sporting houses, and joints of other kinds that comprised the bedrock of New York’s black entertainment and show business.“ Can you talk a little about the influence these musicians and their music had on Gershwin?

RC.There is not much information specific to these connections, but Gershwin’s interest in African-American music, and particularly with those musicians before 1920, opened up that whole realm for him and he was drawn in that direction. Indications are that Gershwin visited the “black and tan” clubs of Harlem during Prohibition, and I think that directed the journey he was going to take in his own music. It isn’t as if he and James P. Johnson hung out together, or anything like that, but they knew each other at that early time since they were both making piano rolls for the Aeolian Corporation. His interest in this music made Gershwin different from other white composers on Broadway. Of course, at the end of his career he ends up doing Porgy and Bess, which he had on his mind from 1925 on.

JJM.When did his peers become alerted to his talent?

RC.After he left his job as a song seller for one with a music publisher, he caught on as an accompanist, working with a range of singers, sometimes in vaudeville, and thereafter on Broadway, where companies rehearsed their personnel. The skills he showed during stints like these recommended him to producers such as Florenz Ziegfeld, composers such as Jerome Kern, authors such as P. G. Wodehouse, and performers such as Adele and Fred Astaire. From early on, he worked with leaders in his trade.

JJM.Of Jerome Kern, Gershwin wrote, he “was the first composer who made me conscious that most popular music was of inferior quality and that musical-comedy music was made of better material. I paid him the tribute of frank imitation and many things I wrote at this period sounded as though Kern had written them himself”…

RC.Yes, from Kern he learned that the richness of Kern’s music is an arena that he loved, and that it stood out among the others. He used Kern as a model from 1917.

.

A musical interlude…George Gershwin plays “Swanee,” which he wrote (with lyricist Irving Caesar) in 1919

.

JJM.“Swanee” was Gershwin’s first hit song…

RC.Yes, in 1919 he and lyricist Irving Caesar wrote “Swanee” – a song about pining for the singer’s southern home – in about 15 minutes, according to Caesar. By the beginning of the 1930s, that song’s sales in sheet music form had topped two million copies, the most of any song Gershwin composed.

JJM.The song was made famous by Al Jolson. How did Jolson come upon “Swanee?”

RC.Following a performance of Sinbad, the show Jolson was starring in, he threw a party in Manhattan, and Buddy DeSylva – a songwriter working with Gershwin at this time – brought Gershwin along, who played his repertory of songs, which included “Swanee.” Jolson was intrigued enough to include it in his next recording session. He added “Swanee” to Sinbad and it became an amazing hit.

JJM.When did Gershwin first receive critical acclaim?

RC.Assuming that “critical acclaim” means endorsement/praise from critics whose job is to evaluate the artist’s work, I’d say the first few days of November 1923 saw that kind of breakthrough. The occasion was a recital in New York’s Aeolian Hall by mezzo-soprano Eva Gauthier, accompanied by Frederick Persson, and labeled a “Concert of Ancient and Modern Vocal Music.” The program included six groups of songs: “ancient,” including Byrd, Purcell, and Bellini; and “modern,” including Hungarian, German, American, Austrian, British, and French. And the American portion, consisting of music from Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, was accompanied by Gershwin, who had helped Gautier choose that part of the program. Half of that portion was composed by Gershwin, and so was its encore.

Deems Taylor, a composer who was also the music critic of the New York World, and Henry Taylor Parker, music critic of the Boston Transcript, heartily endorsed Gershwin’s skill as an accompanist. Both critics were respected masters of their trade, and they both reported that the American portion of the concert had caught on with the audience. Three months later, in the same hall, the Rhapsody in Blue was premiered by Paul Whiteman, which prompted plenty of acclaim.

JJM.When did he begin to get a taste for making money as a songwriter?

RC.Gershwin seems not to have thought much about money, except once in a while when he noted that such and such a contract would bring him an especially rich return. I can’t respond directly to your question, because “a taste for making money” feels somewhat out of key. The man surely knew what his output was worth, but I’ve found little to suggest that he spent much time relishing his financial intake.

JJM.Harry Ruby, a leading Broadway and Hollywood songwriter, said that Gershwin had “an intense enthusiasm for his work. He had passionate interest in every phase of the popular music business.” What kind of business instincts did Gershwin have?

RC.During his years with the Remick firm, Gershwin would get together with other composers and songwriters, and Ruby was one of them. The lad held forth about what it meant to be a composer, and his discourse did not stop with the money a song hit could bring in. Ruby marveled at the breadth and depth of Gershwin’s attitude toward the work that he was doing.

JJM.He was very smart about recognizing opportunity. For example, when Gershwin was coming into his own, radio was just beginning and he spent time cultivating relationships with radio broadcasters who helped disseminate his music over the radio. This doesn’t mean that his goal was to make a lot of money, but it does demonstrate that he saw how this new technology could help him make more people aware of him and his music.

RC.I think you’re right. Gershwin was a determined learner who left school, I believe, once he learned that he was the best judge of the next step he needed to take in the musical career he had chosen and launched successfully.

Regarding your point about how he responded to the opportunities presented by radio, his reaction wasn’t just out of an interest for making money from it, he recognized the potential for getting his music out much more widely.

.

A musical interlude….A 1933 recording of George and Ira Gershwin’s “Oh, Lady Be Good.” The pianist is listed as Buck Washington, and the vocalist is John “Bubbles” Sublett

.

JJM.You describe Gershwin as a “Musical Citizen”…

RC.Yes, I call one chapter of Summertime “Boyfriend, Songwriter, Musical Citizen.” The latter signifies that he was generous with other musicians, known to be ready to give them a hand on musical matters and to coach them along. At the same time, he never stopped taking lessons himself from musicians whose know-how could help him open his own technical doors.

JJM.What made Gershwin so successful at engaging, as you describe his audience, “the many and the few?”

RC.I could begin my response to this question by noting that the variety of audiences Gershwin addressed during his life varied greatly. But a talent he brought with great skill to his music was his gift for fashioning melodies memorable enough to be recognized when they returned. His “audiences” ranged from a friend in the living room listening as the composer played a new number, to the 17,845 people who, in the summer of 1932, witnessed a concert by him and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in the city’s Lewisohn Stadium. Five thousand more would-be listeners were turned away that evening.

JJM.You wrote that the 1924 musical Lady Be Good was “nothing less than a vital contribution to American music.” That show featured songs that are now considered to be essential standards, among them “Oh, Lady Be Good” and “Fascinating Rhythm.” Was this his most successful artistic musical comedy?

RC.No. Of Thee I Sing (1931-33) had the longest run of Gershwin’s musical comedies with 441 performances. Regarding my comment on Lady Be Good, beyond the fact that the show marks when Ira came aboard as George’s lyricist, virtually every one of its songs includes an element of blues music:.another signal of African-American music’s assimilation into Gershwin’s compositions late in 1924, when the thinking that led to Porgy and Bess was just beginning.

JJM.Gershwin’s 1929 musical Show Girl was not a particularly successful show, but you write that it “carries historical significance if for no other reason than that it marks the first and only time that Gershwin and Duke Ellington worked together.” Besides the obvious historic importance of this event, what was the musical significance that this pairing demonstrated?

RC.The presence of Ellington and his musicians seems to have been Ziegfeld’s idea, not Gershwin’s.

JJM.Did Gershwin and Ellington play together, or did they play separately?

RC.Neither. Gershwin’s music-making role in his theatrical career rarely surfaced, perhaps on a show’s opening night, when he decided to conduct the orchestra. Ziegfeld wrote: “It was foolish of me, after spending so much money on a large orchestra, to include a complete band in addition. But the Cotton Club Orchestra under the direction of Duke Ellington, that plays in the cabaret is the finest exponent of syncopated music in existence.”

JJM.Yes, and you wrote that this pairing “suggests the breadth of the American musical landscape’s creative possibilities in the 1920s.”

RC.Yes, that’s right.

.

A musical interlude…Mary Martin sings “I Got Rhythm” from the 1952 studio cast album of .Girl Crazy. The song was written by George and Ira Gershwin in 1930

.

JJM.In the 1930 show Girl Crazy, the band in the pit was Red Nichols and His Orchestra (Charlie Teagarden, Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, Pee Wee Russell, Gene Krupa). This was the musical in which “I Got Rhythm” made an instant impact, and the musical reviews were the best he ever received. Did he hire the band for this performance?

RC.I have no evidence that Gershwin had anything to do with the personnel. Girl Crazy was another Aarons and Freedly production. Surely Red Nichols, the leader of the band, was involved with hiring the band.

JJM.Gershwin conducted the orchestra on opening night…

RC.Yes, he did that at times, and he did that in a couple of other shows also. Once he began in 1927 to play in the summer concerts with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in Lewison Stadium, he appeared there regularly. And once he composed An American in Paris, which had no piano part, he often conducted it in concerts.

JJM.When did he begin contemplating creating music that could crossover and appeal to those who liked popular music but not classical, and vice-versa?

RC.George White’s Scandals of 1922 opened the door to that kind of endeavor. Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra were the featured act in that year’s Scandals, and Gershwin and his lyricist, Buddy DeSylva, wrote a dance-based finale for Act I. He also composed an “Opera ala Afro –American,” which was played in blackface and lasted about 25 minutes. The score of that piece, “Blue Monday,” called for arias, recitative, choral singing, and a number with dancing, plus a melodramatic plot, but it was cut from the show after the opening night in New York. It was a remarkable work for its day, and Gershwin remembered worrying whether he was up to the challenge. But he showed little interest in that work after Paul Whiteman performed it in a 1925 concert.

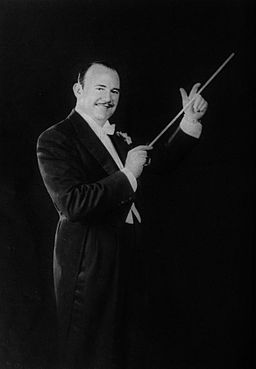

Photographer uncredited / Public domain

Paul Whiteman

JJM.How did the Whiteman/Gershwin connection begin?

RC.After the two collaborated during George White’s Scandals of 1922, Whiteman attended the recital that Eva Gauthier gave on November 1, 1923, at Aeolian Hall, where Gershwin accompanied the American songs. He visited backstage to laud the composer and soon invited Gershwin to write a composition for piano and the Whiteman Orchestra. And by February 1924, on Lincoln’s birthday (Feb. 12), Gershwin and his Rhapsody in Blue were premiered in Aeolian Hall. On June 10 the Whiteman band recorded the Rhapsody, and it became a specialty for the ensemble.

JJM.What gave Whiteman the inspiration to play a concert of jazz music at Aeolian accompanied by Gershwin?

RC.Having recently heard that a rival bandleader, Vincent Lopez, was contemplating a concert, Whiteman scheduled a concert with a theme for his own band: “An Experiment in Modern Music.” .It took place in the same hall where he had recently witnessed his formidable new young friend George Gershwin display his talent and originality. And Whiteman featured in the program a concerto-like piece by Gershwin, who proved to be a brilliant pianist.

See page for author / Public domain

Adele and Fred Astaire, 1919

JJM.In a 1926 letter to Gershwin, Adele Astaire, who seems to have had a romantic interest in Gershwin, thought that Whiteman’s band is an “awful disappointment…it’s a crime to let him do a rendition of ‘Rhapsody in Blue.’ I’ve never heard anything so lousy.” Did Gershwin feel that way about Whiteman also?

RC.I was surprised to come across these letters from Adele Astaire, which go back to 1922, and they come to an end in 1928. I have found no evidence to indicate that Adele and Gershwin had a connection of any kind after 1928. But Whiteman and Gershwin had an important relationship beginning in 1922 and enduring until the composer died.

This performance Adele refers to took place when Whiteman and his band arrived in London in 1926 while Gershwin was there, involved in an overseas production of Lady Be Good! Fred and Adele Astaire were there too in the starring roles they had played in New York.

JJM.You wrote that there may have been a “spat” between the two of them around that time…

RC.There may have been. If I had had more information on the Adele Astaire and Gershwin link I would certainly have put it in the book. Adele’s crush on Gershwin was very strong. She was still in love with him as late as 1928, and I write about whether there might have been some later interest, mentioning the possibility that letters were taken away later on.

JJM.So there is no evidence of Gershwin ever being upset with the way Whiteman was interpreting his music?

RC.He might have questioned it here and there, but he certainly loved it when Whiteman premiered the Rhapsody in Blue in 1924.

.

A musical interlude…A 1965 Carnegie Hall recording of Leontyne Price singing “Summertime,” from the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess

.

JJM.Concerning Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess, which was first performed in Boston in September of 1935 before moving to Broadway, you wrote that “no strategic decision Gershwin made was more important than the one to compose all the opera’s music himself.”

RC.Yes. Dubose Heyward’s 1927 play Porgy was based on his 1925 novel, and it included songs drawn from African-American spirituals. Gershwin chose not to draw from that source, preferring instead to write an opera composed entirely in his own voice.

JJM.How did he prepare himself for writing the opera?

RC.The chairman of the board of the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York decided in 1924 that the Met ought to sponsor ‘a jazz opera,’ and that three composers had been approached .about writing such a work, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, and George Gershwin – and the only one who rose to the bait was Gershwin, who, in April of 1925 wrote an article saying that if a jazz opera were to be composed it should have an all African-American cast and be performed in a theater in which lots of people could see it, like a play on Broadway.

Gershwin read Heyward’s book Porgy in 1925 and was inspired, feeling it was the kind of story he wanted to have for an opera. The two of them got together soon and from that point forward stayed in touch with each other.

JJM.In preparation for writing the opera, as a way of getting acquainted with the culture of the Carolina’s, Heyward encouraged Gershwin to visit Charleston…

RC.Yes, Heyward kept pushing for Gershwin to come south, but the composer, a busy man who now had an especially challenging project in his future, kept his librettist waiting into the next decade. Not until the latter months of 1933 did he set musical comedy aside. But after eight years of contemplating Heyward’s story, he now embarked on the task of composing a full-fledged opera about a community of African-Americans in South Carolina. Aware that such a project would produce little or no income until the work was done, he arranged two ventures to display his musicianship to the public. The first was a concert tour in January and February of 1934, which introduced him to music lovers in nineteen states, the District of Columbia, plus a stop in Canada in twenty-eight days. And the second, after the tour, was taking on a radio broadcast: “Music by Gershwin” twice a week on NBC for fifteen minutes on Mondays and Fridays, which was devoted to his playing the piano and commenting on music by him and that of his fellow composers.

Carl Van Vechten / Public domain

Ruby Elzy as Serena in the original Broadway production of Porgy and Bess .(1935)

JJM.How did he, Heyward, and his brother Ira determine how to divide up the creative responsibilities among themselves, and who had authority to hire the director and cast?

RC .Gershwin’s score, begun late in February, was completed by the end of 1934, and the chore of orchestration engaged him into the following September. Heyward’s libretto was based on his own play,.Porgy. By the time the contract was signed late in 1933 with the producer, the New York Theatre Guild, the libretto was complete. The process of choosing the cast, led by Gershwin with advice from the authors and the musical coaches hired along the way, was well along by the spring of 1935. Gershwin and Heyward agreed that the director of the play, Rouben Mamoulian, would direct the opera, and conductor Alexander Smallens was chosen by Gershwin, as was the chorus leader of the Eva Jessye Choir.

JJM.A cast member, Anne Brown, had a special memory of Gershwin’s reaction to hearing “Summertime” for the first time…

RC.Yes. She was the soprano who played the role of Bess in the opera, and she said later: “I remember so well that day—after weeks of rehearsals…when we had the first full orchestra rehearsal of the finished opera with soloists and chorus on the stage of Carnegie Hall, hired by the Theatre Guild for just that purpose. When the echoes of the last chords of Porgy and Bess had disappeared into the nearly empty hall, we were—all of us—in tears. It had been so moving…George Gershwin stood on the stage as if in a trance for a few minutes. Then, seeming to awaken, he said, ‘This music is so wonderful, so beautiful that I can hardly believe that I have written it myself.’”

JJM.Did the writing of Porgy and Bess dampen Gershwin’s enthusiasm for creating music that was less than highbrow?

RC.He was committed to a career in both spheres of composition, and he once said that it was as difficult to write popular music as it is to write serious music, and that it was hard to find a good theme for a popular song, something that doesn’t already sound like all the others. He also wanted to be sure that if he were writing serious music, it is serious music, and looked forward to the challenge of composing more large works.

JJM.Where was Gershwin headed creatively and geographically at the time of his death?

RC.The concert impresario Merle Armitage talked about how he and Gershwin rode around Los Angeles in 1936 and 1937, talking about art and music. One of the things they discussed was the string quartet Gershwin was working on at the time, and the form it would take – a fast opening movement, followed by a slow second movement – which were based on themes he’d heard during the time he spent with Dubose Heyward off the Carolina coast. He also said that he wanted to get away from Hollywood and rent a cabin in Coldwater Canyon, where he could get his work done. While he had thought of making Beverly Hills his permanent home, he also felt that he would get sedentary in that climate.

When his sister Frances and her family visited her brothers in California during the holiday season of 1936, she said that he told her he wanted most of all to work on American music: symphonies, chamber music and opera. He didn’t feel that he had gotten even a good start on these hopes.

JJM.What was his public identity at the time of his death, and how did America react to his passing?

RC.The New York Herald Tribune said that “not only was he the most popular of American composers, he was perhaps the only American composer whom the Europeans took seriously.”

As for how America reacted to his passing, it might best be described in the words of the jazz critic Otis Ferguson, who wrote “Last Sunday night, the word came over the radio that George Gershwin was dead at the age of thirty-eight, and almost everywhere in the country people must have stopped for a moment. They knew him well, for they had sung his songs.” And the writer John O’Hara said, “George died on July 11, 1937, but I don’t have to believe it if I don’t want to.”

JJM.What can today’s musicians learn from the life and success of George Gershwin?

RC.Gershwin’s God-given talent as a musician enabled him to surpass the work of others in the career he chose. But his spirit of sharing his discoveries and achievements with other musicians also marks him as a committed American musical citizen, and that’s a lesson to learn.

.

___

.

unnamed photographer in employ of Bain News Service / Public domain

George Gershwin, c. 1920s

“[Gershwin’s] days on earth were limited to the summertime season of life. But the music he left behind, endowed with his extraordinary inventiveness and intellectual curiosity, has yet to cease thriving as an evergreen gift to the world.”

-Richard Crawford

.

.

Listen to Fred and Adele Astaire perform Gershwin’s 1924 composition “Fascinating Rhythm,” which was recorded in London, 1926

.

.

___

.

.

Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music

by Richard Crawford

(W.W. Norton & Company)

.

.

___

.

.

Richard Crawford is a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a past president of the American Musicological Society. He has published ten books on American music. He lives in Michigan.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview was conducted by phone and email during the week of February 6, 2020, and hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

Click here to read our interview with Dominic McHugh, co-author of .The Letters of Cole Porter, and click here to read our interview with James Kaplan, author of. Irving Berlin: New York Genius

.

.

.