.

.

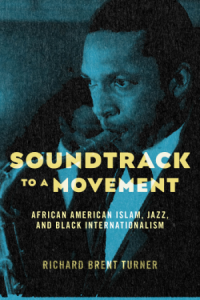

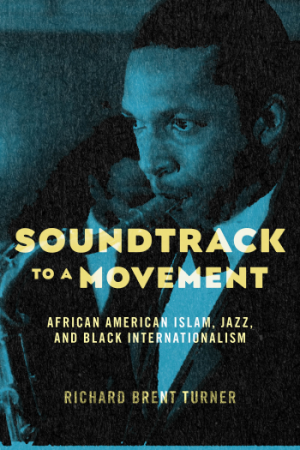

Richard Brent Turner is Professor in the Department of Religious Studies and the African American Studies Program at the University of Iowa, and the author of Soundtrack to a Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism [New York University Press]

.

.

___

.

.

…..In Richard Brent Turner’s compelling book Soundtrack to a Movement: African American Islam, Jazz and Black Internationalism, he argues that from the late 1940’s through the 1970’s, Islam rose in prominence among Black Americans in part because of the embrace of the religion among jazz musicians. Some, like Art Blakey, Ahmad Jamal, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln and McCoy Tyner, converted, while others like John Coltrane, Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie – who never officially converted – were intrigued and impacted by its philosophy and influenced by its musical culture.

…..Turner asserts that Islam and jazz shared common values – Black affirmation, freedom, and self-determination – which were key to the growth of Islam in African American communities, and that it was jazz musicians who led the way in shaping encounters with Islam as they developed a “Black Atlantic Cool.” Malcolm X had a great appreciation for jazz, having immersed himself in it at an early age. As a teenager he danced the Lindy Hop in Boston’s Roseland Ballroom, and especially appreciated the work of Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. His childhood friend, Shorty Jarvis, was a jazz trumpeter.

…..For an example of Islam’s influence on jazz musicians, Turner writes that Blakey “questioned his Christianity and began to protest systemic racism after he was severely beaten by white men while touring with the Fletcher Henderson in the South in 1943. The beating resulted in a head injury requiring surgery to put a steel plate in his head. By 1947, Blakey had converted to Islam and took the name of Abdullah Ibn Buhaina,” and said at the time that “’Islam has made me feel more like a man, really free.’” When he returned to the United States following a 1947 trip to West Africa, Blakey’s drumming and his jazz “were infused with African rhythms and musical inflections and a sophisticated sense of blackness that influenced a new generation of bebop.”

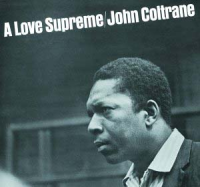

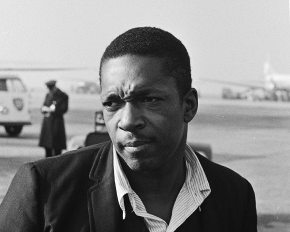

…..While Coltrane never converted, Turner writes that he “repeatedly encountered it and considered Islam” during the 1950’s, and “passionately expressed his African American Islamic spirituality both in his album A Love Supreme, and in his exploration of self-purification, new musical forms, and the Black Arts movement in New York,” while expanding “the geographic and religious frame of Black Internationalism, experimented with new sounds and spiritual traditions from the Third World, played with Muslim artists in his band, and developed a serious interest in Sufi mysticism.” Turner also contends that Coltrane’s embrace of Islamic spirituality “was influenced by listening to Malcolm X,” whose New York speeches Coltrane would often attend.

…..Others who didn’t convert to Islam, like Billie Holiday, nevertheless influenced the political culture. The political activist and scholar Angela Davis writes that Holiday’s song “Strange Fruit” “almost singlehandedly changed the politics of American popular culture and put the elements of protest and resistance at the center of contemporary Black culture.” The song would profoundly influence Muslim converts for years to come.

…..In a February 21, 2022 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Turner talks about the abundant connections of Islam and jazz he presents in his book – a fascinating study for readers interested in religion, popular music and African American history.

.

.

___

.

.

|

Hugo van Gelderen/Wikimedia Commons

John Coltrane; 1963

|

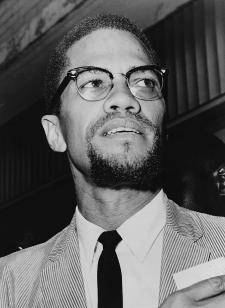

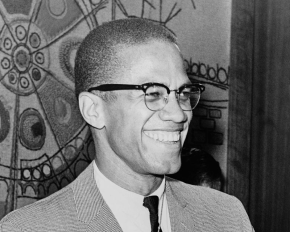

Malcolm X; 1964 |

.

“I equate Coltrane’s music very strongly with Malcolm’s language…they were just about contemporaries…And I believe essentially what Malcolm said is what John played. If Trane had been a speaker, he might have spoken somewhat like Malcolm. If Malcolm had been a saxophone player, he might have played somewhat like Trane.”

-Archie Shepp

.

“Trane’s music…during the last two or three years of his life represented for many Blacks, the fire and passion and rage and rebellion and love they felt, especially among the young Black intellectuals and revolutionaries of that time…He was their torchbearer in jazz.”

-Miles Davis

.

.

Listen to the 1959 recording of John Coltrane playing “Naima,” a song written for his Muslim wife who, while under her watchful eye, helped him kick a heroin addiction. [Rhino/Atlantic]

.

JJM Your book explores the historical connections between jazz, African American Islam, and Black internationalism from the 1940’s to the 1970’s. It demonstrates that during this era, Islam rose in prominence among African Americans for reasons that were related to the embrace of the religion among jazz musicians. What values and goals did jazz and Islam share during this time?

RBT They shared some basic civil rights and Black Power goals, that of Black affirmation, freedom and self-determination, and by expressing these values, jazz and African American Islam both rejected systemic racism. They were both also involved in the construction of new Black notions of masculinity and femininity, as well as the development of a global religious consciousness in the Black world.

JJM What were some of the first encounters that Black musicians had with Islam?

RBT I traced the earliest encounters during the era of Malcolm X’s migration from the Midwest, when he was about 15 or 16 years old, to Boston, Massachusetts. He was deeply engaged in the jazz world as a teenager in both Boston and New York, and was a great jazz dancer of the Lindy Hop who even danced in front of Duke Ellington’s orchestra. So, Malcolm is a very good example of somebody who was developing an evolving understanding of Islam in the early 1940’s at the same time that he was embracing the culture of the jazz world on the east coast.

JJM He loved Ellington’s music, and even shined his shoes in the Roseland Ballroom in Boston…

RBT Yes, and when he moved to New York he became a regular in the Savoy Ballroom – one of the biggest jazz clubs in Harlem – which highlighted great jazz dancers like himself doing the Lindy Hop. At the same time, he had many interactions with Billie Holiday, who was not engaged in African American Islam but was involved with a resistance movement among jazz musicians that thought about social justice issues. At the time, she was singing “Strange Fruit” – the song that so vividly depicted a lynching in the South – in nightclubs in New York.

Billie Holiday; New York, c. 1947

JJM The critics of the music of that time focused didn’t focus much on her activism. Instead, their story about her was about her difficult childhood, her challenges with men, and her drug addictions. But “Strange Fruit” was very clearly impactful for Black Muslim jazz musicians…

RBT That’s right, and it was also impactful on a number of non-Muslim Black jazz musicians who may not have converted to Islam but were influenced by some elements of the religion. Many were involved in social justice movements – for example, opposing lynching and Jim Crow – and because they traveled extensively in Europe during the post-World War II period, they were able to compare and contrast their treatment in the United States with that of Europe. “Strange Fruit” resonated with those involved in the civil rights movement during the World War II era, and it certainly had an impact on the political direction that Malcolm X would take when he converted to the Nation of Islam in the late 1940’s.

JJM You wrote about how the “zoot suit subculture” was “an important lens through which we can understand the evolving urban spirituality of jazz and Islam.” How so?

“Zoot Suiters” outside a Woody Herman performance; Washington, D.C., 1942

RBT The zoot suiters used their clothing to develop a sense of counter culture, a sense of coolness that distinguished them in the jazz cultures, and distinguished them as youth of color from African American, West Indian and Latino/Latina communities on the west coast. The zoot suit itself was a major marker of teenagers and young adults who, because of their racial background and social class, were considered to be the throwaways in American society during World War II. Malcolm X was a zoot suiter in the jazz clubs, and zoot suits were also worn by some of the great jazz musicians during their performances as a way to display their own cool. Cab Calloway is an example of a musician who performed while in a zoot suit…

JJM So, it became a symbol of political resistance or political disguise not unlike what we see in today’s world…

RBT Yes, for a lot of young jazz fans the zoot suit was cool clothing to wear while dancing in a jazz club, but it did become a marker of resistance and counter-cultural values during World War II. The zoot suit riots in Los Angeles in 1943 began when white servicemen on leave physically attacked the Latino/Latina youth for wearing zoot suits – they actually beat them up and tore the suits off their bodies.

JJM How did African American Islam and jazz become synthesized in the minds of Black youth during the 1940’s and ‘50’s?

RBT At that time, a missionary movement from the Ahmadiyya Muslim community began to appear in Boston, New York, and other parts of the United States who were actively connecting themselves in different ways to African American musicians and jazz fans. This actually began in Chicago in the 1920’s, when their first missionary came from India to work with members of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association.

Malcolm X and his friend, the jazz musician Malcolm “Shorty” Jarvis, were both approached by a missionary for the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in Boston in the early 1940’s and were initially impressed because he looked cool; he was wearing a kufi cap and Indian style clothing while walking through Roxbury, the community they lived in at the time. This missionary also had a grand piano in his apartment, where they began studying Islam. This took place before Malcolm X and Jarvis went to prison for robbery.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community developed unique kinds of outreach to jazz musicians, and a number of Black musicians in Dizzy Gillespie’s band began converting, and Dizzy himself read the Quran and thought about it before ultimately converting to the Bahá’í faith.

JJM You write that, while Charlie Parker never converted to Islam, he had a Muslim name…

RBT Yes. After he collapsed on the street one night, he stayed in the Greenwich Village apartment of Ahmed Basheer, a convert to Islam who claims Parker was interested in the religion, knew a little bit of Arabic, and had the Muslim name of Abdul Karim. So, he had this interaction, but we are not sure if he ever thought about converting or merely had an interest because a number of the great jazz musicians at the time were influenced by Islam and were handing out the Quran and other literature.

Art Blakey, playing with the Jazz Messengers in the Kurzaal Concert Hall in The Hague; March, 1963

Art Blakey, the great jazz drummer and leader of the Jazz Messengers, was one of the important musicians who converted to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community during World War II. He was doing missionary work in his apartment in New York in hopes of converting his fellow musicians to Islam. Blakey said he converted to Islam following a concert he performed in the South, when he was attacked by a white supremacist and suffered a serious head injury. This experience made him question how Christianity was linked to white supremacy and to the Jim Crow-era racism the country was experiencing at the time. He said that when he converted to Islam – which didn’t have the long, historical connection to slavery and racism – that he felt like a man for the first time.

JJM Blakey said that “Islam brought the Black man what he was looking for, an escape like some found in drugs or drinking: a way of living and thinking he could choose in complete freedom. This is the reason we adopted this new religion in such numbers. It was for us, above all, a way of rebelling.”

RBT And for some jazz musicians, it was a way of developing a kind of communal masculinity in which they could purify their bodies from the impact of alcoholism and drug addiction. Islam is a religious tradition that focuses on eating healthy food and forbids the consumption of alcohol and the use of drugs, which were circulating through jazz clubs the great musicians were playing in during the 1940’s – 60’s.

At the same time, the Nation of Islam was reaching out to jazz musicians, which is where Malcolm X’s story comes back into the centerpiece of the book. Although he and “Shorty” Jarvis had begun studying Islam with an Ahmadiyya Muslim missionary, that was cut short when they went to prison. While in prison, Malcolm X’s brothers and sisters – who had converted to Islam – began to encourage him to study the Nation of Islam. Eventually, he and Jarvis decided to convert to Islam, and did so in the Massachusetts prison in which they were incarcerated. So, at that time, the Nation of Islam becomes the centerpiece of this story also.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1964 recording of John Coltrane and his Quartet (McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones and Jimmy Garrison) playing “A Love Supreme, Pt. 1 — Acknowledgement [Universal]

.

JJM You write that Malcolm X and John Coltrane were “kindred spirits in terms of their conversion experiences, which turned them away from drug addiction in the jazz world and led them to embrace Islam and Eastern spirituality on Coltrane’s part and the Nation of Islam and then Sunni Musli on Malcolm’s part. They were both jazz brothers in spirit who became known for their ‘openness to self-transformation’ on an international level.”

RBT Yes, although they were on different tracks initially. Malcolm X migrated from Michigan to Boston and eventually New York City, and he came from a family of people who would embrace the Marcus Garvey Universal Negro Improvement Association, which was the most successful Pan-African movement of the 20th century. Coltrane grew up in a family of African Methodist Episcopal ministers in North Carolina before migrating to Philadelphia, eventually becoming a great jazz musician, even while being deeply influenced by his drinking and, eventually, heroin use.

The saving grace for Coltrane is that he lived in Philadelphia – a city that was deeply impacted by Islam – and married a Muslim woman, Naima, which meant he lived for a number of years in a Muslim household. It was in that household that he kicked a heroin addiction over a period of a few days, cold turkey, which turned out to be a wonderful thing for his music. Prior to that he had lost his place in Miles Davis’ band because his drug and alcohol addictions were negatively impacting his performance, but while under the watchful eye of Naima, he believes that God spoke to him, and from that point on he said that he prayed while playing.

We now know that Coltrane had been thinking about converting to Islam as early as the 1940’s, but he said in an interview that he just never got around to it. He was surrounded by so many jazz musicians in Philadelphia who had converted – for example, his pianist McCoy Tyner was a Muslim convert.

The link between Coltrane and Malcolm X occurs in the 1960’s, when Coltrane attended Malcolm’s speeches in New York and had been impressed by his political viewpoints. I would guess that he was most impressed by Malcolm’s global vision and his perspective concerning systemic racism in the United States. This would have been about 1964/65, and Malcolm had left the Nation of Islam by then and was traveling internationally. So, there were definitely links between them, which my book explores extensively.

Malcolm X; January, 1964

JJM At the outset of the book you identify a continuity between Coltrane’s music and Malcolm’s speeches by quoting the saxophonist Archie Shepp saying; “I equate Coltrane’s music very strongly with Malcolm’s language…they were just about contemporaries…And I believe essentially what Malcolm said is what John played. If Trane had been a speaker, he might have spoken somewhat like Malcolm. If Malcolm had been a saxophone player, he might have played somewhat like Trane.”

RBT Yes. At that time Malcolm was trying to embrace a more universal understanding of Islam in the Third World when he converted to Sunni Islam, and at the same time we hear in Coltrane’s music that he had been influenced by Islam, which is especially evident in A Love Supreme. Yusef Lateef, the great jazz saxophonist who converted to Islam, knew Coltrane very well and said that when you listen to that album, and especially when you read the prayer in the liner notes, you are hearing and reading Islamic poetry.

A number of the musicians who played with Coltrane on the various takes of that album were Muslim. McCoy Tyner had converted to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community as a teenager in Philadelphia in the 1940’s, and Rashied Ali and Pharoah Sanders both played on different takes of the recording. So, at different times Coltrane surrounded himself with Muslim musicians, and some scholars and musicians say that if you listen closely to A Love Supreme, at that point where he recites “A love supreme. A love surpreme. A love supreme,” he is actually saying “Allah supreme.”

JJM Was there a spiritual response to A Love Supreme in the Black communities?

A Love Supreme [Impulse] recorded in December, 1964 and released in January, 1965

.

The first edition of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, published in October, 1965 by Grove Press

RBT Yes, because when it was released in the mid-1960’s it connected in many ways to the new kind of spirituality that Black youth were embracing. This was also around the time that Malcolm X was making his Hajj to Mecca and studying at Al Azhar University in Cairo, events that were being reported on in the Black press as well as in many mainstream magazines in the United States. Also, A Love Supreme was released at the time when Malcolm was assassinated in the early weeks of 1965, a little before the time Malcolm’s autobiography was published, meaning that millions of Black people read it and became fascinated by the book’s final chapters that describe his conversion to Sunni Islam and his travels throughout Muslim majority countries like Egypt and Saudi Arabia that signaled a dramatic shift in his global religious consciousness. They were also reading about the Organization of African Unity, whose aim was to resolve issues on the continent and to bring people together. So, all of this gets linked to the Islamic-inspired global unity that Coltrane circulated on A Love Supreme.

JJM Coltrane and Malcolm X are centerpieces to your book, but there are many interesting stories throughout. For example, regarding Duke Ellington you write that he “contributed to a spirituality that affirmed new creative presentations of blackness among urban African American youth in their search for global identity and jazz.” You also write that he was influenced by Coltrane, which impacted his own work in the 1960’s…

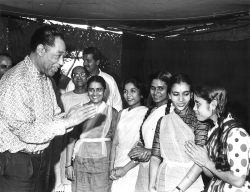

Duke Ellington greets members of the Bhartiya Kala Kendra school of the arts in New Delhi, September 24, 1963. (U.S. Embassy New Delhi photo)

RBT Yes. I’m not making the case that Ellington converted to Islam or thought about it because I didn’t find any evidence of that, but he certainly does talk in his autobiography about the impact of Islam on jazz musicians who were playing in his band, and he especially links that to those musicians who came from Afro Caribbean backgrounds, and who came from backgrounds where Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association was embraced by their families. It is also fascinating to be reminded that during the State Department jazz tours that Ellington participated in, he was impacted by the music he heard in Muslim-majority countries. There are famous photos of Ellington in Pakistan and India walking through the streets of cities while listening to and learning from the indigenous music and the instruments street musicians are playing. While he was in Senegal and listening to music in his hotel room, he made a fascinating connection between African Islamic heritage and his music, saying that he had always been playing “African music.”

JJM Dizzy Gillespie was an early ambassador of jazz music overseas. Why was he considered to be an ideal musician to play for audiences in the Muslim world?

Dizzy Gillespie, c. 1947

RBT He was, of course, one of the greatest jazz musicians, performing in and leading big bands before pioneering bebop. And he was a very smart man who understood that the State Department tours were intended to be a cover-up, in certain ways, for the violent anti-Black racism that was so prevalent in the United States during the era of Jim Crow. The American government – from the presidency to the State Department – understood that its record of white supremacy in this era was hurting the country during the Cold War, and they thought that sending some of the greatest Black American jazz musicians to African and Muslim-majority countries to perform could have the potential to soften its image. So, Dizzy understood that this was an opportunity to play his music overseas, but he also understood that he was being used by the State Department. Musically he used this opportunity to explore different creative directions, and, like Duke Ellington, circulated the streets of different countries in which he was playing – including Muslim majority countries – and in the process became intrigued by the indigenous street musicians, learning about the instruments they played.

At the same time, Dizzy was sensitized to the impact of Islam on jazz musicians because numerous musicians in his big band had been converting to Islam since the 1940’s, which he talks quite a bit about in his autobiography To Be, Or Not…to Bop. He actually looked at the positive impacts of converting to Islam – for example, as a jazz musician he experienced the racism of being Black and traveling in the segregated South to perform concerts, and saw that those who had converted to Islam were not always segregated in restaurants as the other Black musicians were. So, it was interesting how Dizzy used his international travel to connect the African American civil rights movement and his interactions with it with the global anti-colonial movements that were going on in some of the African and Musilm-majority countries where he performed.

JJM Interesting that Muslims were treated differently on the road…

RBT I think some of that had to do with exoticizing Muslims, and that if you are in the Jim Crow South, being a Muslim means that you are not a “Negro,” that you’re somehow a member of a different racial group.

.

A musical interlude…’Listen to Max Roach (with vocalist Abbey Lincoln) perform “Driva Man,” from the 1960 album We Insist: Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite [Candid]

.

JJM But Black Muslim musicians also described the challenges of finding work because they were discriminated against twice – once for their race, and the other for their religion…

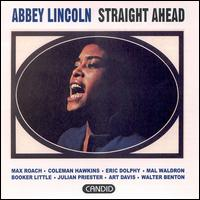

RBT Well, people like Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane always had work, but it was another story for others. Musicians like the drummer Max Roach and the singer Abbey Lincoln, for example, recorded a militant civil rights album, We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite in 1960, and on the cover was a photograph of young Black students desegregating a lunch counter in the American South. Roach had converted to Islam early on in his life in New York City, and married Lincoln, who had converted to Sunni Islam. On this album they depicted the soundscape of horrors associated with enslavement – for example, Lincoln sings the cries of an enslaved person being whipped at the stake. Also on that album, while an African drummer performs Lincoln sings out the names of all the different African countries that emerged from colonialism by the early 1960’s to become independent nations. So, this is a very militant album, and Roach and Lincoln would not back off from their anti-racist activities. For instance, after Patrice Lumumba – then the prime minister of the Congo – was assassinated, Lincoln participated in protests at the United Nations, and she and Roach were subsequently unable to get very much work in New York City for a long time, basically because they were Muslim and active participants in the civil rights movement who brought their political activities into the nightclubs. Roach eventually took an exit from the clubs and into academia, when he became a professor of Jazz Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Abbey Lincoln’s 1961 album Straight Ahead (Candid)

JJM There was a fair amount of pushback toward them from jazz critics. In a Downbeat review of Lincoln’s 1961 album Straight Ahead, Ira Gitler wrote that the recording “is about the slowness of the arrival of equal rights for the Negro…All the musicians on the date are Negro…Pride in one’s heritage is one thing, but we don’t need the Elijah Muhammed type of thinking in jazz. Apart from the conscious racial angle, the quality of her singing is not consistent nor is her material.” So, there were uphill battles to climb in terms of freely linking their creative spirit to their philosophical beliefs…

RBT And also against political protests against anti-Black racism at that particular time, and Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach wouldn’t back off from those protests.

JJM You write quite a bit about how the reconstruction of Black masculinity attracted musicians to Islam. What were the gender politics of Islam, and were they influenced by jazz musicians?

RBT Yes, because you can see that among some of the jazz musicians and jazz fans there was an embrace away from the hyper-masculinity that focused on those self-destructive elements of the jazz clubs and bars, where there was rampant drinking and drug abuse. The conversions to Islam emphasized the purification of the Black body and an embrace of communal forms of masculinity, where musicians connected their performance to Islam, resulting in a new construction of the Black body that can be free from the harmful impacts of alcohol and drug addiction and aspects of hyper-masculinity which are destructive to the African American community.

At the same time, Abbey Lincoln was embracing a transnational understanding of black femininity because she was connecting her performance of music to not only the civil rights movement in the United States – which is the African-American freedom movement – as well as to the anti-Colonial movements on the African continent. So, because of her conversion to Islam, she transitioned from being a nightclub singer – which was the way she was billed before meeting Max Roach, almost as a sex symbol – to a performer who embraced Islam and more politically-oriented music. When she married Roach, he convinced her that there were better things she could do with her music and with her identity as a Black woman that would have a deep impact on global Black freedom struggles. By doing this she could not be commodified as a Black woman by the music industry.

Coltrane, meanwhile, demonstrated a transnational and international Black masculinity by using music of the Third World to provide African Americans with an understanding of themselves as a global people, with links to the liberation struggles in Africa and Muslim majority countries around the world.

JJM What albums would you recommend readers listen to that best demonstrate the connection of jazz and Islam, this “Soundtrack to a Movement”?

RBT A Love Supreme would be at the top of the list. Jazz fans know about it, of course, but when you listen to it again, listen very closely to Coltrane chanting “A love supreme. A love supreme. A love supreme.” It is the kind of chanting that in some way resonates with the recitation of Sufi Mendicants, and when listening you have to decide for yourself if he is saying “Allah Supreme”? I would also recommend that jazz fans read very carefully the poetry in the liner notes, which Yusef Lateef says is similar to reading poetry found in the Quran. I also love Coltrane’s recording of “My Favorite Things,” because you’re hearing him play a popular song of the late 1950’s/early 60’s on his soprano saxophone in an Indian-inspired sound, at a time he was studying Indian musical scales.

I would also recommend recordings by Alice Coltrane, John Coltrane’s second wife, who went into the direction of Hinduism after John’s death. Her albums are fascinating. Pharoah Sanders’ “The Creator Has a Master Plan” from his 1969 album Karma is an important recording, as is the album I mentioned earlier, Max Roach’s album with Abbey Lincoln, We Insist: The Freedom Now Suite.

I also recommend listening to albums by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. In the early years of this group, Blakey chose many Muslim musicians to perform on the albums, and of course the term “jazz messengers” has an Islamic connection, with Muhammad being the “messenger” of Islam. Anything by Yusef Lateef is important because he was one of the earliest jazz musicians to convert to Islam, and one of his early albums, Eastern Sounds, features him exploring instruments that were indigenous to the Muslim world. He’s an inspired saxophonist, and an inspired flute player. Lateef and Coltrane were planning to do concerts at Lincoln Center that would demonstrate the African and Islamic roots of jazz, and along with the Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji were going to travel to Africa to explore the roots of his music, and there certainly would have been Islamic linkages there. Unfortunately, Coltrane died before they could make this trip.

.

___

.

“The stories of the jazz musicians in this book exemplify a larger history of American musicians, fans, dancers, religious folk, and political activists who practiced African American religious internationalism, which encourage black people in diaspora to think of themselves as more in concert with Africans and the ‘darker races of the world’ than with Europeans and white Americans. They used these ideas to construct powerful strategies against racial oppression in the United States. For many musicians, then, jazz provided a springboard for global perspectives about blackness, self-determination, social justice and resistance, and liberation.”

-Richard Brent Turner

.

.

Listen to the 1962 recording of Yusef Lateef playing “Blues From the Orient” [Universal]

.

.

___

.

.

Soundtrack to a Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism [New York University Press]

by Richard Brent Turner

.

Richard Brent Turner is Professor in the Department of Religious Studies and the African American Studies Program at the University of Iowa. He is the author of Jazz Religion, The Second Line, and Black New Orleans, New Edition, and Islam in the African-American Experience, Second Edition. Turner is a 2020 American Council of Learned Societies Fellow.

.

.

Praise for the book:

.

“A tour de force of interdisciplinary research that identifies, explains, and analyzes previously underexplored links between expressive culture and social identities. For both expert and novice readers, African American Islam and Jazz is filled with delightful surprises. Turner’s chapters on Black urban life in Boston and Philadelphia delineate the rich social and historical contexts out of which the musical texts of bebop music emerged. His careful attention to empirical detail reveals southern and Caribbean migrants to these cities to have been neither ruthlessly uprooted nor seamlessly transplanted, but instead positioned inside complex struggles for self-defense, self-determination, and self-activity.”

-George Lipsitz, author of How Racism Takes Places

.

“Muslim jazz artists inspired interest in Sunni, Ahmadi, and the Nation of Islam communities, but the Islam of swing, bebop, hard bop, and free jazz was often not so much a theology as it was a politics, a poetry, a culture of cool. Richard Brent Turner’s book reveals how Islam breathed the spirit of supreme love and international Black liberation into America’s greatest music. It is required reading for everyone interested in the entangled story of jazz and Islam.”

-Edward E. Curtis IV, William M. and Gail M. Plater Chair of the Liberal Arts, Indiana University, Indianapolis

.

“Richard Brent Turner’s new book greatly expands our knowledge of the rise of Islam as an alternative religious vision among African Americans in the twentieth century. This much-needed study cogently depicts the invention and recrafting of Black notions of masculinity and “Black Atlantic coolness” that gave structure and shape to both Black militancy and jazz styles during the 1940s and postwar period. Very importantly, Turner contextualizes the intermingling of jazz and Islam against the backdrop of a burgeoning Black internationalism that still powerfully informs contemporary diasporic consciousness.”

-Claude A. Clegg III, author of An Original Man: The Life and Times of Elijah Muhammad

.

“Turner’s powerful and well-written book taught me new things on just about every single page, new things about jazz much, about Islam in America, and about how those two spheres intersected in the lives and experiences of African Americans. Spanning several decades in the exploits and activities of various Islamic groups, as well as some canonical African American figures, this book provides us with a distinctively new soundtrack for the stories we tell ourselves about black political and religious life.”

.

-John L. Jackson, Jr., co-author of Televised Redemption: Black Religious Media and Racial Empowerment

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on February 21, 2022, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician Editor/Publisher Joe Maita

If you enjoyed this interview, click here to read a conversation among the religious scholars Tracy Fessenden, Wallace Best and M. Cooper Harriss, who discuss the “Religion ‘around’ Langston Hughes, Billie Holiday and Ralph Ellison,” or click here to read an interview with Gerald Horne, author of Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music

.

.

Click here to learn how to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician newsletter

.

.

.

One comments on “Interview with Richard Brent Turner, author of Soundtrack to a Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism”