.

.

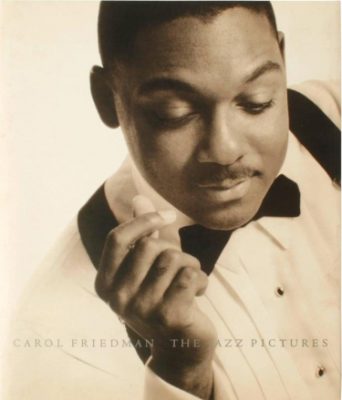

Carol Friedman

.

___

.

…..During a career now spanning over three decades, the esteemed New York portrait photographer Carol Friedman’s iconic images have appeared on hundreds of album and CD covers. Her poignant, often spontaneous work – a generous sampling of which is on display within and following the interview – includes the photographs of, for example, legends like Jimmy Heath, Ron Carter, Lena Horne, Chet Baker, Eubie Blake, Cecil Taylor, Nina Simone, Miles Davis, and Sarah Vaughan, and of contemporary artists like Sullivan Fortner, Chucho Valdes, Terence Blanchard, Terri Lyne Carrington, Wynton Marsalis, Dianne Reeves, Christian McBride, Lisa Fischer and Joey Alexander.

…..An avowed jazz fan, Ms. Friedman’s background in music includes positions at .Elektra. Entertainment, .Blue Note,. and .Motown Records. as creative director. Now an independent photographer, designer and author, she is working on several book, music and film projects, including a film on the late jazz singer Abbey Lincoln.

…..Her lifelong work of distinction in the world of jazz photography is worthy of recognition. Ms. Friedman agreed to participate in the following interview that includes conversations and stories about her childhood interest in photography, her entry into the world of photographing jazz musicians, her creative mentors, and, of course, the musicians themselves.

…..I am excited to present her work to readers on such an illustrious scale. My thanks to Ms. Friedman for allowing. Jerry Jazz Musician .the opportunity to visit, and to publish many of her photographs for your enjoyment.

.

.

This interview took place via telephone on April 29, 2019, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

All images copyright Carol Friedman, used by permission of Carol Friedman

.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

.

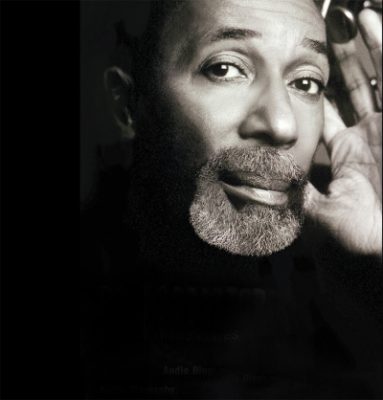

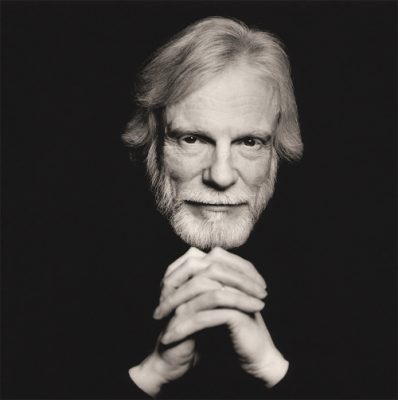

“Carol is ‘Exhibit A’ of the people she photographs. She is a creative artist who is forever changing. Her photos tell the story of her love for the people she digs and their surrounding environment and the company they keep. I am completely enamored with her work and personality.”

.

Jimmy Heath

.

.

_____

.

.

JJM. What did you want to be when you grew up?

CF. I wanted to be an artist. And a photographer, once I found out that there was such a thing. I asked for a camera when I was about five years old, and I don’t think that first camera ever left my hand. Until the next camera. There was a series of cameras…

JJM. Did your parents give you this first camera?

Carol Friedman at age three

CF. Yes. My dad was a serious amateur photographer and I was a favorite subject. I must have asked for my own camera because picture taking was a dialogue that I wanted to be part of. It was a language. So, I was given a Brownie Fiesta, and I remember posing my sister and friends, telling them where to stand and what to do. Looking back, it’s pretty funny that at that age I was already imposing my will on these very young subjects. By the time I was eight, I was on to my Instamatic,. and still posing everyone.

JJM. When you were young, did you enjoy looking at the photography in magazines?

CF. Not really. I don’t think magazines were part of my world other than reading Seventeen magazine like all of the young girls. I wasn’t yet aware of photography as a medium, or as an art. I was focused more on art than photography. I was drawing all the time.

JJM. As you were finding your own way, and as you became aware of photography as an art form, do you recall having a favorite photographer?

CF. Not until I studied with the great French portrait photographer Philippe Halsman. It was just a single course, called ‘Psychological Portraiture.’ I was 19, and had no idea that there was such a thing as a portrait photographer. Halsman told stories about his nuanced preparation and the seduction that went into making portraits of his famous subjects—from Marilyn Monroe to Einstein. His premise was that if a photograph does not reveal a deep psychological insight about its subject then it is not a successful portrait. I remember saying to myself, “This is what I am!” I was all in. We all had to buy our own tungsten light, reflector and stand and were taught “Hollywood glamour lighting.” I started shooting portraits of my family and friends with the .Minolta .that I had been given as a high school graduation present.

A few years later, at the School of Visual Arts, I was exposed to the cool art photographers of the day—Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Duane Michaels, and Robert Frank. And portraitists like August Sander and Richard Avedon. As students, we were encouraged to mirror the work of whomever we admired, I suppose as part of the process of finding our own style. The work of these rebel reportage photographers was a new frontier for me. I asked my grandfather for the money to buy a second-hand .Leica, .and I hit the streets with it.

JJM. What music did you listen to when you were in your late teens?

CF. Led Zeppelin, Jethro Tull, the Allman Brothers, Blind Faith, The Doors, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell…

JJM. So, the classic rock artists…

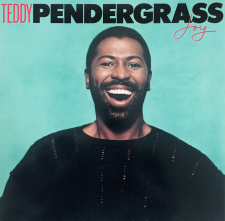

CF. Yes, and certainly the Beatles and the Stones. John Lennon and Crosby Stills and Nash and the R&B singers followed—Aretha of course, and Marvin Gaye, Al Green, Teddy Pendergrass, and Bill Withers.

JJM. How did you come to love jazz music?

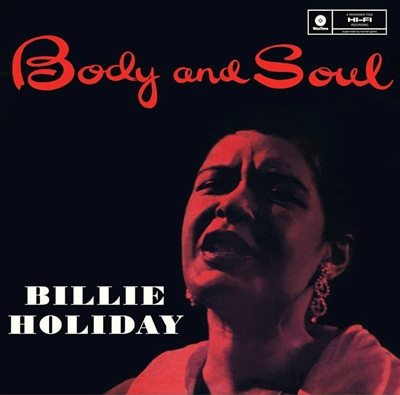

CF. I actually came back around to it, because when I was growing up in Brooklyn, the soundtrack of my father’s record collection was a constant—Billie Holiday, Lester Young, Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra. So the foundation was there and when I later re-discovered jazz it felt like home. The DNA had been set.

JJM. That is such a great set of musicians to learn how to appreciate the music from. You are lucky that you had that.

CF. No question. I am so grateful for that early exposure, and as you say, look at who they were – it was the power line.

JJM. How did you determine that photographing jazz musicians would be a creative path for you?

CF. . When I first enrolled at SVA, it was as a fine arts major. But I couldn’t commit paint to canvas and finally became a photo major and then had to select a thesis. One night, I accidentally heard Chet Baker performing at Strykers, .a neighborhood jazz club. He was singing “Just Friends,” and that was that. I returned the very next day to ask for a waitress job. It was a double compulsion. I wanted to be near the music and was also curious about capturing it.

Chet Baker, 1976

I started out keeping my. Leica .behind the bar, shooting the musicians as they played, but these club pictures were terrible. The venue had zero romance— no real bandstand and not even a spotlight. When Chet returned to .Strykers for his next engagement there, I somehow got up the nerve to ask if I could photograph him where he lived. I was still in Diane Arbus /Robert Frank reportage mode. He agreed, and I photographed him and his entire family. I knew that these pictures were all wrong even while I was shooting. I asked if I could come back. On that second visit, Chet suggested that we “go for a ride.” Chet, his wife Carol and I ambled across to a parking garage and my heart skipped at the sight of his Mustang convertible. When Chet got behind the wheel, his bandstand personality, his demeanor, his musical presence – it was all there. This was a breakthrough moment for me, and it defined what my process and my artistic goals would be, going forward.

JJM. In addition to your experience working with Chet Baker being a catalyst for an approach and style, did it put your career on the map?

CF. No, that was years away. I was still waitressing and still in college, but the jazz portraits did become my photography thesis. I was also learning about the music and piecing together the lineage. I put together a hit list of artists to photograph, to assemble a collection of images, perhaps for a book. This was just something I was pursuing on my own – cold calling the musicians and setting up sessions in their homes, or just showing up and shooting impromptu in club dressing rooms, hotels, and in the kitchen of the Village Vanguard. I was freelancing, just barely, for the jazz magazines. At one point I was shooting the covers for Contemporary Keyboard. That was a very big deal at the time.

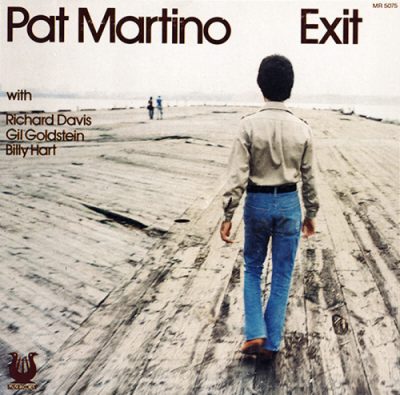

As soon as I graduated, I took my first full time job as Art Director for John Snyder’s Artists House label. That opened a world for me. Ornette, Chet, Art Pepper, Gil Evans, Jim Hall, James Blood Ulmer, David Liebman, Charlie Haden, and Hampton Hawes were all recording for the label and I had the opportunity to know and photograph these geniuses. Art Pepper in his hotel room, Ornette and Charlie on the street, Gil at his apartment in Westbeth. Then Muse Records came calling and I did my very first album covers for them. Pat Martino’s Exit, .Hank Jones’s .Bob Redux. I had to work with the same approach and shoot them all on location, as I didn’t have strobes or a studio.

JJM. Is there a shoot you did for Muse that you especially remember?

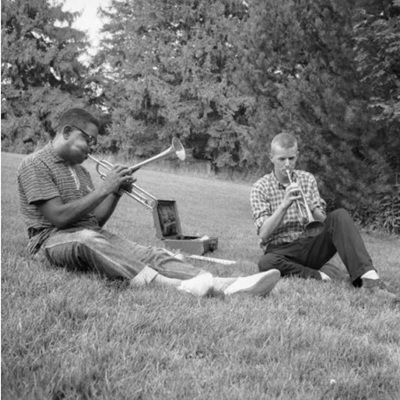

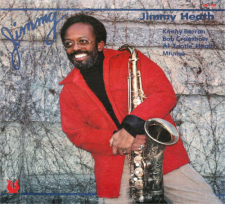

Jimmy Heath’s 1979 album, Jimmy (Muse)

CF. SSure. My session with Jimmy Heath truly defines the art of improvisation. I got on the subway to go to Jimmy’s home in Queens, not knowing what I would find when I got there, but sure that there would be a spare wall to shoot him against. There was none. Every inch of the walls were covered with pictures, so I was in a silent panic. I asked if we could go through his closet, and was spurred on by a great red jacket that belonged to his wife Mona. Jimmy got a kick out of the fact that I was putting him in his wife’s jacket. I suggested that we take a walk around the neighborhood, but there were no spare backgrounds to be found, just grass and trees and sky. I eventually found my blank slate, and it was under the overpass of the Grand Central Parkway. Improvisation in its finest form. All of the aesthetics came together.

JJM. When did you move on to the studio?

CF. I had always loved the work of Avedon and Irving Penn, but with no knowledge of studio lighting, I couldn’t even dream of approaching this style. But one day while shooting Dexter Gordon and Johnny Griffin in a hallway, I discovered that I could create a faux white background with my tiny .Vivitar .flash mounted on top of my . Leica. .I still have that flash. People assume that my portraits of Eubie Blake or the Jones brothers were done in the studio but it was the flash-on-camera. In a dressing room. This was a way to combine reportage with a faux version of a studio. Aesthetically, I fell in love with this absolute blank slate and never looked back. No distraction from the emotion of the image. And this inspired me to take the next step. I moved into my loft on Grand Street, bought my first strobes and set up my studio there, in my home. I’m still there, all these years later. And I love the history of all that’s gone on here.

JJM. You became best known as a studio photographer, and it seems that you did not do a lot of live shooting, but one shot you took of Chet Baker on the bandstand at the Village Vanguard is quite stunning – it is one of my favorite photographs of him.

Chet Baker at the Village Vanguard, 1976

CF. Thank you, Joe. I love this image of Chet as well. There were three sets of music at the Vanguard in those days. I lived right around the corner in a sixth floor walkup on West 4th Street. So after getting off work from Strykers, I would stop in for the last set at the Vanguard to shoot. The beautiful light on that bandstand created a magic blank slate of its own; a black one. Sometimes I developed the film when I got home, in my bathroom, and then made 16 x 20 prints the next day in the school darkroom. Most of the photographs of mine that are hanging on the Village Vanguard walls were printed in that darkroom.

JJM. Who were your artistic mentors?

CF. I can’t count Halsman as a mentor, but he had a great influence on my work and his words always stayed with me. Besides his dictum about revealing the inner emotional life of one’s subjects, he also said—and I still have this in my original class notes— “Be ready for accidents—master them, create them.” This seems to speak directly to the art of improvisation, doesn’t it?

Except for Gordon Parks – and could there be anyone better than that – my mentors were not visual artists; they were music producers and record label heads who championed me. I was lucky to count Jerry Wexler, Bruce Lundvall, Quincy Jones, and Jean-Philippe Allard as my big brothers and am to this day humbled by their admiration of my work. The first time I photographed Quincy in my studio, decades ago now, he saw that although I was unhappy with where I had just positioned him, I was hesitating to change it. He said “Jerry Wexler told me that in his [recording] sessions, you have to miss ‘em quick.” When I didn’t understand, he clarified – “If it’s not working, change it— immediately.” The dynamics that go on in the recording studio are similar to what occurs on the set, because whether the musicians hit the groove on the first take or an hour in, that’s what everyone is after, finding that groove, which is the same thing that happens on a photography set. And you can’t chase it – it has a life of its own. Bobby Short was right there in frame #1 of the first roll, and Don Pullen took a while to get there. Sometimes it takes many hours.

JJM. How deep does your knowledge of an artist need to be in order to effectively shoot the subject?

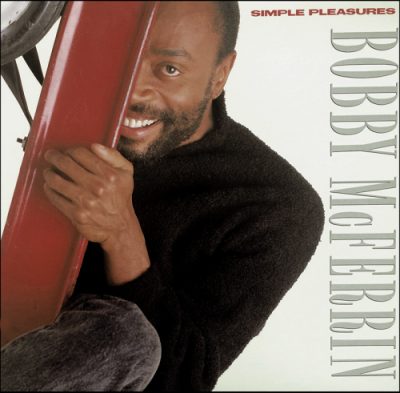

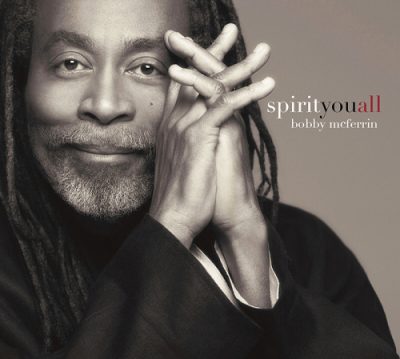

CF. I usually know an artist’s music when I am asked to work with them, so I am already a fan. And have an understanding of their musical lineage. If I am on assignment to shoot their album cover, I do go back to listen to the music that preceded the new recording, and look at the prior album covers as well. What I don’t want to do is to be derivative. Above all, the goal is for the imagery to represent the spirit of the recording that they have just made. It’s all about the music. I have photographed certain artists for multiple recordings, so it’s even more essential that we are not derivative stylistically. There were four Bobby McFerrin records and five Teddy Pendergrass album covers, and they look very different from one another. They had to.

JJM. Have you ever had a job or jobs with people who you are not a fan of, or of someone you don’t have a lot of respect for?

CF. Only once, and it was way off the jazz landscape. I was asked to shoot the album cover for Eric B. & Rakim, who were important innovators in hip hop. The label’s art director told me that Eric and Rakim had a specific idea, which was that they wanted to be photographed inside a bank vault, sitting on a pile of money. I told him that no thanks, I was not going to take that picture. He was incredulous that I would walk away from this very well paid shoot. I requested a meeting with the artists. Eric came to my studio and I asked him why he would want to have the type of album cover that all the lesser artists emulating them were doing. I suggested taking a portrait of them instead and showed him the session I had just done with Teddy [Pendergrass]. He said, “You’re on!”

But other than that – and this project did end up being something that I very much cared about shooting – I have not found myself in a situation in which the subject is not someone whom I admire. I would not be able to do what I do otherwise. Not only do I have to respect my subjects, but I kind of have to love them, because what happens during the session is intimate business. There is trust involved. On both sides. Jazz artists, almost without exception, are emotionally unguarded. How can they not be? Emotion, and shared emotion, is central to what they do, night after night – as is instinct and improvisation. And so it goes on my set. It’s the same dance.

JJM. You have done a lot of work for Blue Note during your career, and you talked a little about doing work with Muse Records. Did you go on to work for other jazz labels as well, and has this work been done primarily as a freelance photographer?

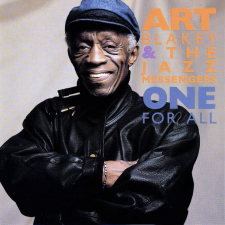

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ 1990 album, One For All (A & M)

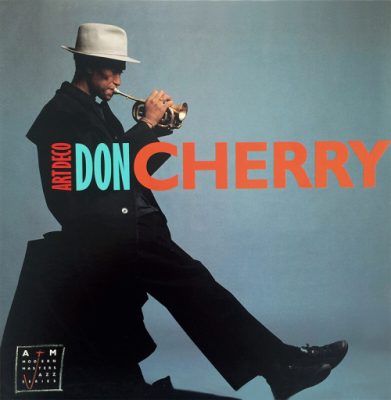

CF. Yes, except for Elektra and later Motown, my work has been as an independent. After leaving Elektra, Bruce Lundvall asked me to come to Blue Note as their chief photographer and unofficial art director. Because I was not on staff, during this same period – this was the 1990’s – I was shooting covers for most of the other record labels as well. My tenure at Elektra was a game-changer in that having bigger budgets for the pop music acts afforded me certain luxuries as a photographer – renting locations and props, hiring stylists – all of which, at the time, were prohibitive for jazz budgets. It was absolutely unacceptable to me that female pop artists were provided with hair and makeup artists and wardrobe stylists but Sarah Vaughan was not. So I had to figure that out. For example, when A&M asked me to photograph their jazz series, which included albums for Art Blakey, Cecil Taylor, Don Cherry and Sun Ra – or likewise for Verve’s Gitane recordings for Shirley Horn, Kenny Barron, Abbey Lincoln, and JJ Johnson – there was no budget for any of these accoutrements, but I had made my contacts, could ask for favors, and go to the designers directly, offering them album credit. If Art Blakey does not deserve a Ralph Lauren leather jacket and club chair, who does?

JJM. The covers of Blue Note are so revered, stylistically, from Francis Wolff’s photos and Reid Miles’ designs…When you do work for a company like Blue Note, with this rich history, how does that impact your own work? How do you get your own vision or voice to appear with all that history before you?

CF. I absolutely revere those covers, both for the photography and the graphic design. They are the gold standard. When Bruce asked me to come aboard, he was not interested in a continuing homage to that collective of cover art. He wanted the look of the label to have more in common with the mainstream, so I didn’t go that route at all. But I was able to bring on great graphic designers like Henrietta Condak and Carin Goldberg. Their knowledge of typography was unparalleled. Those covers also reflected the trends in fashion and in advertising at the time. But everything comes full circle. Some of my recent covers mirror certain aspects of that aesthetic.

JJM. What is an example of a contemporary cover that you’ve done that would embrace that Blue Note aesthetic?

CF. When I do reference that aesthetic, it’s more about being attuned to certain classic typefaces, to a spare approach that sets forth a particular elegance. The typography and color palette for the Gil Evans Orchestra package reflects a retro feel to some degree. But above all, the cover art must reflect the music. For Chucho Valdes’ new recording Jazz Batá, the music is incredibly vibrant, so a staid sensibility would be absolutely wrong. The music really dictates the aesthetic. I also like to let the emotion of the photograph take the lead.

JJM. When you are hired to do a photo shoot for an album cover, do you also have control over the graphics?

CF. For the past several years now, yes, I do the graphic design as well and deliver the finished package to the labels. I have come to love design as much as photography. In the beginning it was a way to keep my photographs from harm. Sad but true. Time after time, the wrong photograph was chosen or printed poorly or the right image was eclipsed by substandard design. In the old days, great art directors were present at my sessions and truly made me a better photographer. And their impeccable graphic design made the photograph sing! No more. So I do my best to keep the bar raised on my own.

JJM. Proper collaboration is so critical in this kind of art, isn’t it?

CF. Yes, and my collaboration now is with the artists. It starts in discussion, long before we are on set. It’s all about expressing the core of the music, and their artistry – at this point in time, and for this particular recording. By the time we meet on the set, we are clear about what we’re after.

JJM. Do you have a favorite story you would like to share about a photo shoot? Is there one in particular that is memorable for you?

Sarah Vaughan, 1982

CF. There are so many memorable moments, so I will give you a couple of quick stories. I absolutely loved my session with Sarah Vaughan, and all of its chapters. It was for the Crazy and Mixed Up recording. I had conceived the cover to be a take on the “What Becomes A Legend Most” fur campaign, and asked Sarah to bring her mink coat. She arrived for the shoot with her gowns and the coat, but begged off, promising to return the next day. And then dictated a grocery shopping list for the chili that she would cook when she came back! To ensure that she returned, I told her that she would have to leave the mink coat behind. Ransom was in place. The next day, she came back and began cooking first, then went into makeup, telling my photo assistant to stir the chili. Then we got down to the business of the shoot. I love the photograph but the album cover is a perfect example of what I spoke about earlier. They cropped the photograph, used bad typography and then did a very poor job printing it. What a shame. And this renowned label did not pay me, but that’s another story.

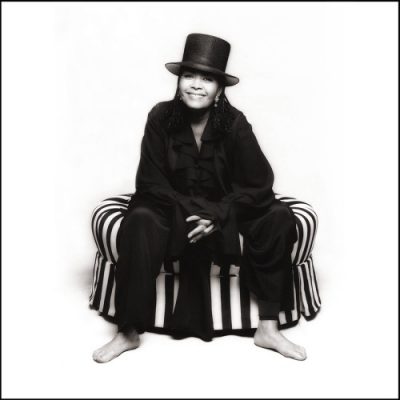

I loved all of my sessions with Abbey Lincoln. She was so sophisticated as far as fashion went, so it was great fun to play Barbie together, with her as Barbie! Also with Lena Horne and, of course, Nina Simone. Nina was perhaps my biggest challenge ever, because of her complexity. This session was for the cover of the last recording she made, .A Single Woman.

I had photographed Charles Brown for the cover of his album .These Blues, in his costumed regalia. A year later, I was summoned back to California to shoot his next release. We knew one another by now, and Charles left the door ajar when he was applying his eyebrow makeup. When I saw him in this ‘before’ state, I was struck by his handsome elegance. It took persistence, but I convinced him to go.natural. .No wig, no makeup, no cap and no glittery costumes. I told him he looked just like a beautiful basketball player and this was the truth. That photograph is enormously satisfying to me. He loved it, and gave up the costume in his performances as well.

Outside of the studio, there are many singular pictures that were not part of a lengthy session, or of a session at all. The photographs of Eubie Blake happened in an instant, as did the picture of Quincy Jones with Count Basie. I had to incite those moments, and fast, versus having hours to emotionally cajole on set. Either way, that moment of magic is the prize, and it is achieved by any means necessary. The portrait of Eubie against the white wall in his dressing room and the portrait of Cecil Taylor in the studio with the same white background are indistinguishable stylistically, yet one took three minutes and the other three hours. Cecil brought a bottle of Verve Cliquot to the studio and danced to Marvin Gaye for the entire second part of our session. He loved “Come Get to This.”

JJM. Did he ask that you play that music, or did you play it for him?

CF. I played it for him.

JJM. Did you know he would respond that way, or that he would even like Marvin Gaye?

Terrence Blanchard, 2001

.

Teddy Pendergrass’ 1998 album Joy (Elektra)

.

Lena Horne, 1994

CF. I have a pretty good instinct about what to play for my artists. I have much more fun putting together the music for my shoots than I do thinking about the lighting – not that I don’t think about the lighting, but that part is easy. I do prepare a custom soundtrack for all of the artists. Terrence Blanchard recently reminded me that I played .Clifford Brown with Strings .for him and in the photograph from that session, where he is sitting in profile, his finger is up because in that moment he is acknowledging Clifford. The music is extremely important. When I was to shoot Teddy Pendergrass for the cover of his Joy recording, I preplanned a surprise joyful moment. Once Teddy was in place, I cued up Harold Melvin and The Blue Notes “The Love I Lost,” ready to shoot his reaction. The cover photograph of him was the image clicked in that moment.

The only person that I didn’t feel completely confident about choosing the music for was Lena Horne. There was so much wonderful music to choose from, particularly by Strayhorn and Ellington, but something didn’t feel quite right, so I popped into her recording session to ask her whether there was anyone in particular she would like to listen to during our session, and without skipping a beat, she answered “Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles.” I would have gotten that totally wrong! In my favorite photograph of her from that session, she is listening to Aretha sing “Don’t Play That Song For Me.” I must have hit the back button on that track 17 times! Aretha energized that image.

JJM. In the introduction to your book The Jazz Pictures, the jazz writer and cultural critic Stanley Crouch wrote “The photograph is the biography of someone’s soul.” The music you play is a way to bring that soul out…

CF. Yes, that is so true. It is an important aspect of harvesting emotion – in inciting emotion. Certain music can also mainline a subject straight into their own nostalgia – their formative years, their lineage, their own discovery of the music. So, I often play key recordings by the musical idols of my subjects.

I also want to say that it is very important to me to flatter my subjects. To give them their idealized image of themselves. I can be extremely pleased with a portrait but I am not fully gratified until I know that my subject feels that way. Nina Simone is not the complimenting sort, but she did tell me “Carol, you made me look like Audrey Hepburn, and I thank you.”

JJM. Do you ever find inspiration for a photograph from a title of the recording?

CF. Yes absolutely, the title is part of the equation. When I was asked to photograph the genius brother and sister gospel singers BeBe and CeCe Winans for an album called .Relationships, .the record company wanted a location shoot, so I scouted a beautiful weathered interior in Tennessee. There was furniture and plenty of wardrobe, and props, and gorgeous light streaming in the window, but in the end, the cover was a very close portrait from the top of their heads to the bottom of their chins, because, this spare and intimate portrait perfectly defined the title. For Sullivan Fortner’s recent recording, Sullivan wanted to pay homage to the cover of Oscar Peterson’s. On The Town, .in which Peterson is looking through a camera. We tweaked Sullivan’s original title and called it .Moment’s Preserved .(also as a nod to Irving Penn), kept the concept of the camera, but did a re-imagined modern version of the theme. He was truly wonderful to collaborate with. The camera that Sullivan is looking through on the cover is actually my Dad’s very first camera. The continuum of inspiration.

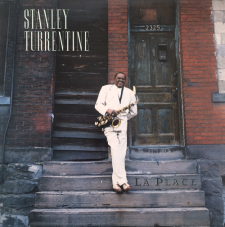

Stanley Turrentine’s 1989 album La Place (Blue Note)

I want to also say that album artwork was of course affected by the continually shrinking album formats. In the era of the 12 inch album my subjects were often photographed on location, and in full length. Stanley Turrentine, for instance, wanted to be photographed in front of the house he grew up in for his Blue Note album .La Place. .When the industry scaled down to a six inch CD, I had to have conversations with my artists about why it was no longer a good idea to shoot them within a larger context, as there would be no emotional contact between them and their fans by virtue of the fact that their tiny heads would not even be expression-readable. The emotional connection can never be sacrificed.

JJM. That is an interesting point. We often think about the artistic challenges for musicians who evolved from recording on an LP length canvas versus a CD, but that certainly has to also challenge photographers and designers in a significant way…

CF. Absolutely so, and we did what we had to do. You saw Adele and Beyonce and Alicia Keys – all of the superstars in quick succession – use only a close-cropped photograph of their faces as cover art. And now there are virtually no CD’s. So the six inches was reduced to the half-inch image which now accompanies streaming services like iTunes.

JJM. Records are making a comeback. Does that revive your work at all?

CF. Sure. I am so happy that vinyl is back. I am actually afraid to fire up my turntable because there is surely a mania ahead if I go down that vinyl road! But in terms of my work, it doesn’t make me want to pull the camera back again. I’m in close-up land forever now. If someone has the ability to look at the art before they hear or buy the music, I want them to make an immediate connection with that artist; to perhaps learn something about them, to want to know them, and to want to hear their music. With vinyl, you have that immediacy and connection by virtue of holding the art in your hand.

JJM. What are your plans for the immediate future?

CF. I am working on a couple of books simultaneously, and I also hope to complete my long overdue Abbey Lincoln film. The books cover my work with jazz artists through the years. One is a collection of portraits that will include passages about the making of the pictures, and the other will feature images from the earlier reportage work.

While researching the great Chuck Stewart’s images of Abbey [Lincoln] and Max [Roach] I had the opportunity to go through Chuck’s contact sheets and learned that his greatest images had never even been printed by him – and this was across the board. He told me that he was shooting so many record album covers, and given that the front and back cover and a publicity picture was all the record companies wanted, he never printed anything else. To some extent that was my experience as well.

So it’s been fun to mine my own archive and discover so many surprises – pictures that I passed over and didn’t deem worthy at the time. They seem like jewels now. I love the portrait of Sarah [Vaughan] but now I equally appreciate the documentation that I did of her in the recording studio.

JJM. Can we expect to see the Abbey Lincoln film soon?

Abbey Lincoln, 1995

CF.I hope so. It’s near completion and now we need a fiscal angel. I started the film in 1990, so it’s beyond overdue. I used to fret about it not being done, and Abbey would say, “Oh, don’t worry, you have plenty of time,” but at some point she said, “Carol, it’s time.” Part of the reason for the delay was that she kept evolving as an artist. Talk about non-derivative, Abbey was never derivative, and always in ascension. So I had to keep documenting it all.

The other issue was financial, because I was shooting on film, not video, so through the years, I would work a little, save a little, and shoot a little. Abbey did get to see the rough cut and absolutely loved it, and I am extremely happy about that. I am also re-editing. She was prescient about so many things and now the world has, in essence, caught up to Abbey Lincoln. This is a modern film about a genius woman who was way ahead of her time.

JJM. Well, you are awfully busy on important work, and we look forward to seeing the results. I hope you are able to share this work on a large scale…

CF. TThank you. This music is truly a life force and I want to contribute all that I can to it. I have been blessed in being able to combine art forms that I love and it is a joy to share it.

JJM. What do you hope your artistic legacy will be?

CF. I think I am going to leave that to others, but I will say that for many years now, I have pretty much dedicated myself to capturing the spirit of this music and the collective of geniuses who create it. When people look at my body of work, I hope that they will feel connected to the heart and the soul of it all … the continuum of inspiration.

.

.

_____

.

.

Three artists comment on Ms. Friedman’s work

.

.

.

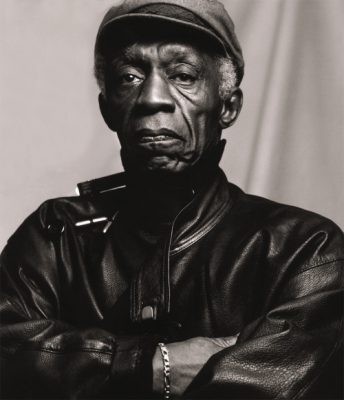

“I’ve known Carol for a very long time and knew her work even before I met her. It’s a pleasure to know that my guess about her sensitivity, about her concern for musicians and her love for the music, which helps her photograph and capture all these feelings, was proven right. I love and will miss her as I get older and she gets younger, so it seems to me. She’s a precious gem in our sea of black sand.”

.

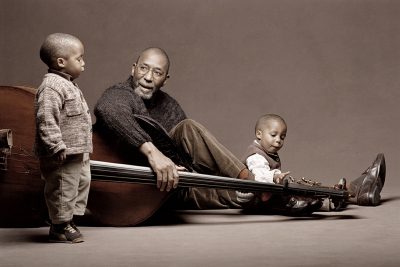

.“Carol has a way of making the artist whom she’s taking a picture of feel comfortable in her presence. You hardly notice the person who is .capturing the specific image that she sees, which is part of her scope of the bigger picture … that the person who is being photographed, in this case me or my grandkids, we’re just kind of hanging around, looking around, and then there’s this great shot of us. She has the skill and the ability to make everyone not see her until she has done her work. I love that concept.”

Ron Carter

.

.

___

.

.

.

“Carol Friedman’s photographs are a direct reflection of her class, poise, her keen eye for natural beauty. It was truly a pleasure to work with such an amazing artist.”

Sullivan Fortner

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

“Carol is exhibit A of the people she photographs. She is a creative artist who is forever changing. Her photos tell the story of her love for the .people she digs and their surrounding environment and the company they. keep. I am completely enamored with her work and personality.

I remember when we met and she took the first shot under the overpass near my apartment in Queens. It was used on my album titled “Jimmy.” She was very young and excited at finding a new musician in New York.

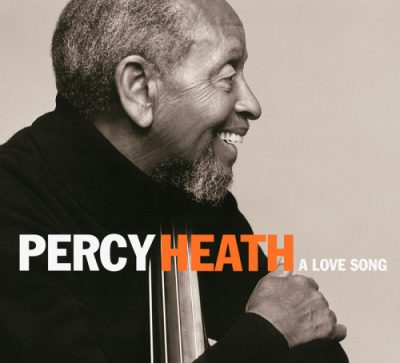

Carol is a humble but very intelligent friend of the Heath family. She has photographed my brothers, Percy and Albert “Tootie” and my .son Mtume. All of Carols photos whether, for album covers, lobbies, publications or films are extraordinarily creative. WE LOVE HER WORK!”

The Heath Family

.

Jimmy Heath, Carol Friedman, Mtume, Albert “Tootie” Heath, 2018

.

.

.

_____

.

.

A selection of photographs by Carol Friedman

.

.

Betty Carter, 1976

.

.

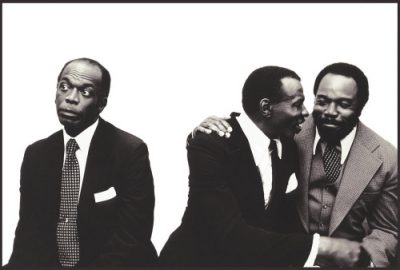

Hank, Elvin, and Thad Jones, 1977

.

.

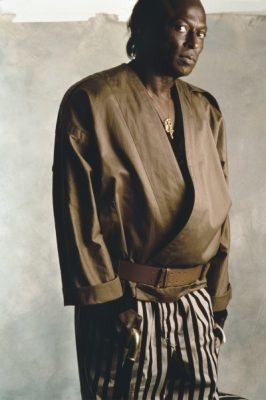

Miles Davis, 1984

.

.

Gerry Mulligan, 1990

.

.

Art Blakey, 1990

.

.

Abbey Lincoln, 1993

.

.

Nina Simone, 1993

.

.

Randy Weston, 1996

.

.

Dianne Reeves, Shelia Jordan, Christian McBride and Lisa Fischer, 2016

.

.

Joey Alexander, 2016

.

.

Ingrid Jensen, Terri Lyne Carrington, Tia Fuller, 2018

.

.

Sullivan Fortner, 2018

.

.

Roy Haynes, 2019

.

.

.

A selection of album covers by Carol Friedman

.

.

Pat Martino, Exit, 1977 (Muse)

.

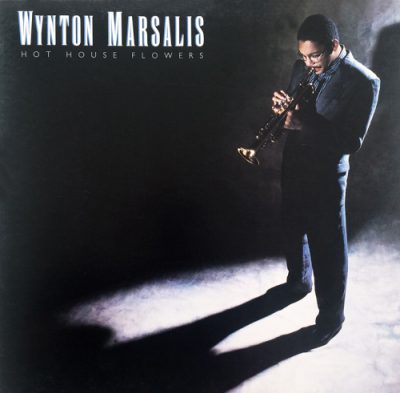

.

Wynton Marsalis, Hot House Flowers, 1984 (Columbia)

.

.

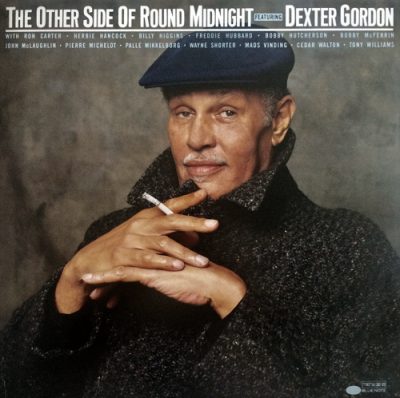

The Other Side of Round Midnight, featuring Dexter Gordon, 1985 (Blue Note)

.

,

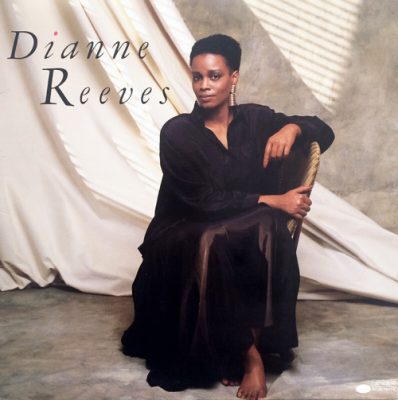

Dianne Reeves, Dianne Reeves, 1987, (Blue Note)

.

.

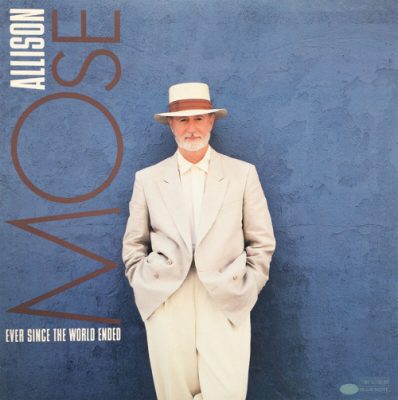

Mose Allison, Ever Since the World Ended, 1987 (Blue Note)

.

.

Bobby McFerrin, Simple Pleasures, 1988 (Manhattan)

Bobby McFerrin, Simple Pleasures, 1988 (Manhattan)

.

.

Don Cherry, Art Deco, 1988 (A&M/Horizon)

.

.

Percy Heath, A Love Song, 2004 (Daddy Jazz Records)

.

.

Bobby McFerrin, Spirityouall, 2013 (Sony)

.

.

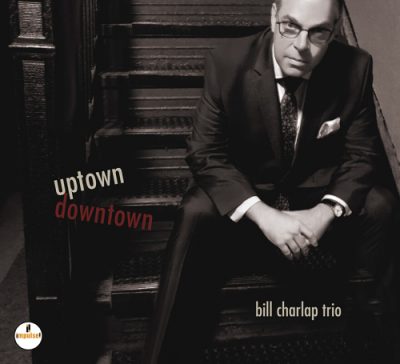

Bill Charlap Trio, Uptown Downtown, 2017 (Impulse!)

.

.

Sullivan Fortner, Moments Preserved, 2018 (Impulse!)

.

.

_____

.

.

.

.

In the days following the telephone interview, I posed a question via email, asking Ms. Friedman to talk about three of her all-time favorite jazz images.

.

CF. I started collecting jazz photography books some time ago, and. through the years, .acquired wonderful prints of a few. of my favorite images.

I am in absolute awe of the work of the master image makers who documented the music long before I came along. After initially knowing them only through their photography, it was my supreme pleasure to later share close friendships with Herman Leonard and Chuck Stewart. Despite the generational divide, Chuck and I were kindred spirits and had great respect for one another’s work. And Herman loved the fact that he and I had photographed many of the same jazz artists in two completely different shifts … that I “took over” where he left off. I was beyond flattered when Herman asked if I would consider trading prints with him. .I own several of their photographs now and their brilliant work blesses my home.

Three of my favorite jazz photographs:

.

Herman Leonard photograph of Billie Holiday. Hollywood, .1953

.

© Herman Leonard Photography, LLC

.

I purchased this print in New Orleans many years ago, long before I met Herman. It captures .a moment. which I have witnessed many times—a performer .waiting in the wings. just .before being .announced and taking the stage, but of course it is wonderful for that performer to be Billie.

I was drawn to this quiet moment where she is out of the spotlight, her delicate features in profile. .And the wedding dress-style gown adds to the innocence. Herman was .known. for his compelling. spotlight performance pictures but he was also a master. at shooting. from. an undetectable perch; ,never intruding on the private moments .he had discovered.

.

*

.

Dennis Stock photograph of Mary Lou Williams. New York, 1958

I love this photograph for many reasons. Stock has apparently posed Williams at the piano—or perhaps this was her idea—but either way, her comfort in being in front of Stock’s lens is apparent.

This is a portrait of relaxed elegance and self-possession. I love the serenity of her aura, and the painterly elements of the. natural light, the parakeet, the framed art and the simple. white dress. The composition is exquisite. We feel as though we’ve been invited into her home.

.

*

.

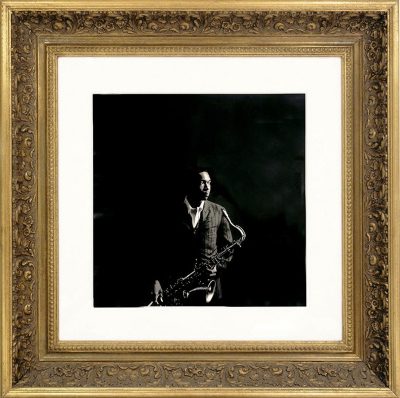

Chuck Stewart photograph of John Coltrane. New York, 1966

.

(collection of Carol Friedman)

.

This photograph hangs in my home as.a.shrine to the brilliance of John Coltrane and.Chuck Stewart. It is evident from the intimacy of his.pictures.that Stewart’s subjects.loved and trusted him. And he never took their trust for granted. In this rarely .seen.uncropped.full-frame. image from this famous session, Coltrane .seems .suspended in .a private time and place, and absolutely fine with allowing Chuck to quietly and incisively. make a record of .this inner sanctum. There. is a double love and .respect going on here.that is palpable.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

by Carol Friedman

.

.

___

.

.

Click to visit Carol Friedman’s website

.

.

.

This interview took place via telephone on April 29, 2019, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

.