.

.

photo Nina Hollington

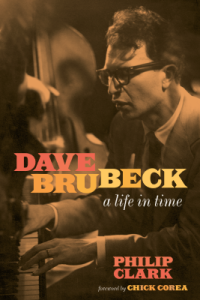

Philip Clark, author of Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time

.

___

.

….

…..

…..The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s 1959 album Time Out has long been recognized as one of jazz music’s most important and enduring recordings. While that album remains essential (and enjoyable) listening – Paul Desmond’s “Take Five” may be the most recognizable jazz recording ever – Brubeck’s genius is that through much of his 66-year-long-career he managed to construct music that displayed complex technique while simultaneously earning wide commercial success.

…..Brubeck’s most notable achievements came during a time of major societal and cultural change, and often in the face of critics who at times found his music too technical and bombastic. He was an enigmatic and extraordinary pianist, composer, and band leader, and a subject ripe for biography.

….. In the introduction to Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time, the author Philip Clark writes that his plan for the book was to “thread his life back through the times that formed it.” Much of the book revolves around conversations and details that emerged during a ten day period in 2003 when, according to the book’s publisher (Da Capo), the author was “granted unparalleled access” to Brubeck. The result is that “Brubeck opened up as never before, disclosing his unique approach to jazz; the heady days of his ‘classic’ quartet in the 1950s-60s; hanging out with Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Miles Davis; and the many controversies that had dogged his career.”

…..Clark’s book is an impressive blend of expert musical analysis, the sociology that surrounded and informed much of Brubeck’s art, and an appropriate amount of esteem reserved for his legendary subject.

…..In a May 26, 2020 interview, Clark discusses his book with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita.

.

“Searching for the Next Dave Brubeck.— Just You, Just Me” – a poem by Julianne DiNenna – follows the interview

.

.

___

.

.

photo courtesy of the John Bolger Collection/used by permission of the author

Dave Brubeck poses at home, mid-1960s

.

.

“There’s a way of playing safe, there’s a way of using tricks and there’s the way I like to play, which is dangerously, where you’re going to take a chance on making mistakes in order to create something you haven’t created before”

-Dave Brubeck

.

.

.

Listen to Dave Brubeck’s 1962 recording,.“The Duke” from the album Brubeck Plays Brubeck

.

___

.

JJM . What was the first Dave Brubeck album you bought for yourself, Philip?

PC .The first album I bought for myself with my own pocket money was Blue Rondo, which was by the 1987 Dave Brubeck Quartet. In 1987 I would have been 14 or 15, and albums seemed so expensive in those days. It probably cost seven pounds, and my mum made me save up my allowance for three weeks in order for me to buy it. So that was the first one I bought, but the first one I heard was Time Out, when I was about five years old. My dad is a painter and our family mythology is that he painted most every night with the music from Time Out playing in the background, and as soon as “Blue Rondo A La Turk” came on I would run into his studio dancing and cheering. I would keep myself awake just so I could hear “Blue Rondo,” and I think by the time that “Strange Meadowlark” came around I was falling asleep, so I never quite got to ”Take Five” until a bit later. There was just something about the sound of “Blue Rondo” that gave my stomach butterflies at such an early age – like I was listening to an amazingly exotic sound that I wanted to be inside. That is really where my interest in Brubeck began.

JJM .Since your father was a painter, is it possible he was attracted to Time Out because of the album cover art, or did he buy the record after hearing it on the radio?

PC. He studied in London at the Royal College of Art with Peter Blake in the 1960s, and during that time heard lots of jazz in London. He would very casually tell me that he would go hear the Modern Jazz Quartet on one night, and the next night he would see Count Basie or Errol Garner. He actually saw the Brubeck Quartet in 1964 when they came to Newcastle in the Northeast of England, and the story my dad told is that he and his friend were a little late in arriving, and since it was a capacity crowd there were additional seats placed on the stage, which is where they ended up sitting, only a few inches from Dave’s hands. Apparently, after the performance Dave turned toward my dad and nodded at him. Incredible to think that the man he nodded at was his future biographer’s father.

“Blue Rondo” was the start of my interest, and I subsequently plundered my dad’s record collection, which included lots of classical music but also records by people like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Pee Wee Russell, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Goodman, and Louis Armstrong. Everything I have done in music started with that experience with “Blue Rondo.”

JJM . What is your musical background?

PC. I was initially a composer, and attended the university in Huddersfield in Yorkshire, which is famous for the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. I received my Masters in Composition and Philosophy from the University of Sussex, where I subsequently did my PhD, and then did composition work for many years, including a big piece that was played by the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Interesting things emerged from that but in the back of my mind I was more interested in the spontaneity and culture of improvisation.

JJM . How did you get into writing?

PC . After I finished my PhD, I taught for a little while and.needed to earn some additional money. Brubeck happened to be touring in 1998, and by that stage I already had a correspondence going with him. At the time there was a British magazine called Classic CD who ran a composing competition that I won, and afterwards I informed the editor that Brubeck would be touring and since I could get an interview asked if he was interested in my writing a feature article. He said he was, and after about two-and-a-half months writing it, the article appeared in 1999. I thought this was great – I got free CDs, and got paid for the article. A few days after the article appeared the editor asked if I wanted to write a feature for the next month, so I did a piece on Charles Mingus.

Around that same time a magazine called Jazz Review started, edited by Richard Cook, whose death from cancer in 2007 was a big loss to British journalism. At one time he wrote for Classic CD, which is when we met, and I told him I would like to write for Jazz Review, so he gave me some stories. After that it just snowballed. I started writing for The Wire, then Gramophone and newspapers. There wasn’t any great plan, it just sort of fell into my lap.

JJM .You interviewed Brubeck extensively during a 2003 tour of England. What did you do with the 2003 interview materials before writing this book? Did you utilize any of the content in any way?

PC . It was used for a piece in Jazz Review, but he gave me much more material than I ever could have used in a piece like that, and I would say that I hadn’t heard at least 80 percent of the material since 2003.

Much of the interview was while riding on the coach [bus] with Dave throughout a good portion of the tour schedule. He would play the gig, do the obligatory signing of CD’s after, and then we would get on the coach and go back to London. Also on the coach were Dave’s wife Iola and the other members of the Quartet at the time – the bassist Michael Moore, who had an amazing career playing with everyone from Bill Evans to Gil Evans to Benny Goodman, the drummer Randy Jones, the saxophonist Bobby Militello, and the roadies and the manager. It was a happy atmosphere on a very luxurious coach.

JJM .Brubeck’s career is so dominated by “Take Five” and the album Time Out that one could forgive him if he didn’t want to talk with you about it. Did he open up with you about Time Out?

PC . Yes, with limits. He loved talking, and in one instance he was remembering an album he made with Anthony Braxton when, for whatever reason, we moved into a conversation about Time Out, and I sensed immediately that this topic would be problematic simply for the reason that he couldn’t remember much about it. There was certainly more reason for him to remember it than the Dave Digs Disney sessions or any of his other recordings, but I think he had been asked about it so much that he had become as confused as anybody else where fact ended and myth began. The quartet finished the sessions in the summer of 1959 and I am sure that he hadn’t listened to any of the outtakes or any of the other material between then and 2003. He was 82 years old and being asked to remember something that had happened 50 years before. So yes, it was a strange thing to ask, and there are still unanswered questions about certain aspects of how Take Five evolved.

.

A Musical Interlude…Listen to The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s 1959 recording,.“Blue Rondo a la Turk” (with Paul Desmond, Joe Morello and Eugene Wright)

.

JJM .When Columbia issued their 50th anniversary edition of Time Out, they didn’t include any of the outtakes, but you’ve heard things other people haven’t. What did you discover in those studio outtakes that you’d like to share with us?

PC . Lots. I will start with “Blue Rondo a la Turk.” There is one complete take of the piece on which they play the composition more successfully than the take that we know, where Dave fumbles during the first 45 seconds. There is none of that. But the reason they didn’t use this version is because the solos were a mess. At the time of the recording they hadn’t yet worked out the concept of how to improvise during “Blue Rondo” – they had yet to get to the realization that the whole point of the piece is that it is a collage or mosaic. The jazz musician’s instinct is to improvise around the melodic compositional head of the piece so, in a rather self-conscious way, Dave imposes his theme on top of the blues changes; and on every chorus he stops and starts a new idea in an attempt to get something started, but nothing catches fire. Everything trips over itself – it is just too top-heavy. On the take that was released on the album everything is stripped right back, and Desmond’s solo is like an absolutely seamless Matisse line drawing that reaches an arc and disappears, and Dave’s solo uses a little motif at the beginning that reappears at the end. It all seems so very seamless. They must have finally realized that the whole nature of “Blue Rondo” is the 9/8 rhythm that Dave heard in Turkey, and inserted inside the 9/8 composition are choruses of the blues, and to really improvise on the piece faithfully they had to realize that the improvisation needs to contain different material from the composition – there’s your mosaic. Once they get it, of course, it flies.

“Take Five” is a hornet’s nest. Until the day he died, Dave insisted that the “Take Five” rhythm that everybody now knows was the same 5/4 rhythm that Joe Morello used as a warm up before a gig, to which Desmond would play along. Dave said that Joe brought this rhythm to the studio when they recorded “Take Five.” However, when I get to the Brubeck archive in Stockton, California and excitedly get the session tapes, I discover that the initial take used a completely different rhythm. Dave’s vamp is in place but Morello is inserting this awkward, counter-intuitive upside down Latin rhythm that he is whacking away on the rims of the drums, and it could just never quite sit in the groove – it is tripping the piece up. They attempt it about 12 times and the more Morello tries to make the rhythm work, the further he gets away from it, and eventually he just can’t play it. You can feel the frustration in the room, so Dave tries to calm everything down. Even the melodic line hadn’t quite settled yet. It is a minor theme and Desmond keeps slipping into the major, and the transition between the A section and B section hasn’t slotted into place. So, it is definitely “Take Five,” but if Morello had stuck to that rhythm, it definitely would not have been a hit record. It’s like everything else on that album – delicate like chamber music, but Morello is thundering away in the background.

During my research for the book I got in touch with Sony to see if they could locate tapes of subsequent recordings, but after several months of waiting, they responded by saying that the tapes were never returned, so we don’t know what happened between their first attempts at recording “Take Five” and to how it eventually became the version we know. We can’t know what conversations went on in between the two sessions and how or why Morello decided to drop that first rhythm and to get into the groove we know, but it was absolutely the right thing to do.

JJM . The first instance of their playing music from Time Out live was at Newport in July, 1959. What was that like?

PC . It’s mixed. It’s been quite a long time since I listened to it but the head of “Blue Rondo” almost tumbles apart. It feels jittery and nervous, and though they get through it, it is not slick or comfortable. But the solos are fantastic and they really drive it – they had definitely bought into the idea about how to improvise on “Blue Rondo.” The interesting thing about “Take Five” is that at the time no one knew the piece. During all later live performances, when Dave starts the vamp the audience goes nuts, but in this case he starts and he plays it into a void, there was no response. At the end of the performance of “Take Five” the audience was incredibly enthusiastic, so Dave recognized that the piece had a star quality to it from the beginning.

Charlie Parker, August, 1947

JJM .A part of your book that was fascinating was a reminder that Brubeck toured for a while in 1953 with Charlie Parker. Is there any evidence, or from your discussions with Brubeck, that they may have played together?

PC. I wish there was evidence of this. That tour was the Dave Brubeck Quartet in a package with the Charlie Parker Quintet – not Dave and Charlie working together. There were once rumors of a tape of Bird sitting in with the Brubeck Quartet, but nothing has ever turned up. Don’t get me wrong, the idea of finding a tape of Dave and Bird would be one of those things on every jazz fan’s bucket list, but something that makes me pretty certain it never happened comes from a document of a speech that Dave or Iola gave at a civil rights conference, and on the document Dave lists all the black musicians he recorded with, and there is no mention of Charlie Parker. If Dave had played with Charlie Parker he would have been very proud about it, and would have spoken of it.

Dave told me about being on a coach with Parker, talking with him about what Darius Milhaud had taught him, and the whole concept of polytonality, and he shared thoughts with him about Stravinsky, Bartok, Ravel, Satie and Debussy. He would have an in-depth conversation like that with Parker on one night, but on the next Bird would be so out of it and unapproachable, presumably desperate for a fix. One time Parker was being sought after by the mob, seeking cash for drugs, and Dave remembered advising him not to get involved with these people. So, there was a close bond between them while they were on the road, but their friendship, for whatever reason, isn’t well documented.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the Dave Brubeck Octet play “Love Walked In,” recorded sometime between 1946 and 1948, and released in 1950

.

JJM . You write at length about Brubeck’s Octet, which recorded several years prior to Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool” orchestra but wasn’t released until after Birth of the Cool…

PC. That depends on how you define “record.” When Brubeck’s Octet first recorded in 1946, Miles was still playing bebop in Charlie Parker’s group. But those early Brubeck recordings with the Octet were never meant for commercial release, they were recorded simply because someone turned up with a recorder possibly for some kind of personal use. So even though Brubeck technically recorded first, they weren’t released until long after the Birth of the Cool band had officially recorded. A lot of people – mostly east coast critics who didn’t like Dave – tried to make mischief of that, saying that the Brubeck Octet was simply a watered-down version of the Birth of the Cool band. Dave found that very irritating. There is a letter in the Brubeck Archive from Iola Brubeck to Ralph Gleason – who had written an article for Metronome magazine comparing the Birth of the Cool band with the Octet – where she really rips him apart, complaining about how he misrepresented Dave’s music in the press.

Once you realize that these early Brubeck Octet recordings were made in 1946 and unreleased until 1950 it is easy to understand that it was a case of synchronistic thinking. The Octet were mixing compositional elements with improvisation and polytonality and ideas from Stravinsky and Ravel, and obviously the Birth of the Cool is not dissimilar, but they are also a million miles apart. Just because these two bands existed in the same world at the same time, it doesn’t necessarily mean that there is any connection between them. They were both post-war groups and because of the war there was an interest in what had been going on in Europe, and Dave picked it up in one way, and Miles and Gil Evans and Gerry Mulligan and John Lewis on the east coast in another. They are different trains on the same track.

JJM . Brubeck was marketed as a purveyor of modernism right from the start, and it even showed up in the Octet’s album covers…

PC . Yes, all these years the discussion has been about the cover of Time Out, and it was always sort of there from the start.

JJM .The covers reflect the idea of what modernism looked like then, and communicated the notion that what Brubeck was playing was progressive and out-of-the-ordinary…

PC . The idea of modernism was an exotic strand of American culture at the time, and Columbia Records honed in on that as a marketing tool. Lots of people were afraid of modernism, of course, but a lot of people were attracted the idea of modernist painting, literature, architecture…

JJM .Clearly, Columbia was concerned about it. There didn’t appear to be a lot of support in their offices other than the now legendary A&R man George Avakian and the label’s president Goddard Lieberson…

Brubeck, c. 1951, on the cover of Dave Brubeck Quartet (Fantasy Records 3-5)

PC Yes. Avakian was primarily a jazz guy based in New York, but he was also very interested in composers like Elliott Carter and John Cage and Lou Harrison, so he understood that wider context of American music and felt Brubeck slotted right into that. Brubeck had a childhood fascination with pianists like Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, and Billy Kyle, but was also fascinated by Schoenberg, Bartok, Stravinsky, Milhaud and Ravel, so the Brubeck aesthetic comes from putting those together, slamming one on top of the other.

How must it have been in 1951 for his audiences at the Hickory House and Birdland who were in those New York clubs to hear bebop – they must have thought Dave was bat-shit crazy, with his pointy-elbow harmonies, with angular melodic leaps and clusters and polytonal harmonies and solos that didn’t have the typical shape – beginning an idea, reaching a peak and then tailing off. His solos often put different sorts of material together in a gladiatorial way. It is very difficult now to imagine what hearing Dave Brubeck for the first time in 1951 must have been like. What an incredible kick in the solar plexus that must have been. His music had nothing to do with the east coast jazz they had understood.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to “Ode to a Cowboy” from the 1957 album Jazz Impressions of the U.S.A. (the first recordings featuring Joe Morello on drums)

.

JJM . A major event in the history of the Dave Brubeck Quartet is when Joe Morello replaced Joe Dodge in the band, and Paul Desmond’s reaction to it. You talked to both Brubeck and Morello about that. Did they add anything to what is already known about that time?

PC .I did a phone interview with Morello for Jazz Review many years ago, and am really pleased I did because it added a lot to the book. Before he arrived, the Quartet was essentially Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond, accompanied by a bassist and a drummer, whose main responsibility was to keep the basic nuts and bolts of the harmony going so that Dave and Paul could do their work on top. Dave was able to mess around with the rhythm and the harmony secure in the knowledge that wherever he landed rhythmically or harmonically everyone will be on the same page. Of course, as soon as Morello arrived the power dynamics of the group shifted fundamentally, and there were now three great virtuoso musicians, and Paul simply couldn’t handle it.

The first time this particular version of the Dave Brubeck Quartet played together was at the Blue Note in Chicago. During the show Dave handed Morello a long drum solo, which was part of the agreement with Morello, who wanted to be featured as a soloist. He lifts the roof off during the solo and people stand up and applaud, and Desmond is so furious he storms off the stage. Dave and Paul then have an argument backstage, during which Paul demands that if Joe doesn’t go, he would. Dave was assertive in telling Paul that Joe isn’t going anywhere, and he did so because he realized that the sort of ideas that had incubated in the Octet – the polyrhythms and the time signatures and ideas of superimposing different meters at the same time – were near impossible with his previous drummer Joe Dodge, who was a very fine drummer but wasn’t the great technician that Joe Morello was. He couldn’t negotiate those odd time signatures and he wasn’t particularly interested in soloing. So, that is why Dave put his foot down with Desmond, because he understood that musically it made sense, and that with Morello he could take the group to new heights.

Carl Van Vechten / Public domain

Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond, 1954

The next night, Dave came to the club unsure if Desmond or the bass player Norman Bates were going to show up, and if not, he and Morello would have to play alone. Just as Dave and Morello got to the bandstand, Desmond and Bates walked in and everything seemed fine and they played. That didn’t mean Paul was happy, and the resentment went on for months – everything Joe and Paul said to each other had to be passed between Dave because they wouldn’t talk to each other.

Eventually they did become close, but near the end of the classic Quartet in 1966 or so, Iola wrote a letter to Columbia Records producer Teo Macero, saying that the Columbia people had gotten the billing wrong – that it must read in the order Dave, Paul, Joe and Eugene [Wright] or Joe would get upset. That ranking showed he was the third important voice in the group. Darius Brubeck, Dave’s eldest son, told me that while Paul and Joe did become friends, that power dynamic never quite resolved itself. There were lots of factors why the classic Quartet ended, and that was among them.

JJM .You used the word “assertive” in describing Dave’s defense of his decision to hire and retain Joe in the face of Paul’s demands. I found him to be assertive on many occasions. An important example was during a phase in his career that was shaped by cultural politics and the civil rights movement. For example, during a tour of the American South in the late 1950s he had to be assertive with racists in defending the right of Wright to perform with his group…

The Dave Brubeck Quartet (Eugene Wright, Joe Morello, Brubeck, Paul Desmond), on the cover of the 1959 album Gone With the Wind

PC .As far as Dave was concerned, there was never any question about this – the Dave Brubeck Quartet was the Dave Brubeck Quartet, it just so happened that his bass player was black. You either took it all or nothing. Dave stood by Wright and cancelled much of that tour of the Deep South, costing him about $400,000 in today’s money, which didn’t please his manager Joe Glaser, who felt Dave should bring Norman Bates back to play the bass on the tour.

Wright joined just before the Quartet had set off on its State Department sponsored tour behind the Iron Curtain – a tour whose purpose was to promote the ideals of American democracy. Yet, two nights before they left on that tour of these countries who would be happy to welcome Eugene Wright, in their own country the Dean of a major university wouldn’t let Eugene on stage unless he played behind a curtain. Dave saw that racism revealed hypocrisy and malice, and considered his musicians as brothers.

JJM .You were able to meet with Wright in Los Angeles…

PC . Yes. I knew as I was writing this book that I would have to make a pilgrimage to meet Eugene, even if it was just to shake his hand, so I set up a visit for October of 2017 in Los Angeles, where I spent an extraordinary afternoon with him. He was 93 at the time, and the warmest, most gracious individual I could ever hope to meet. We talked for three hours, and he told me about playing with Basie in the 1940s, and a train journey that he took with John Coltrane during which Coltrane expressed concerns that he may not have what it takes to be a good musician. It was one of those experiences where you feel the depth of history in someone. That conversation also clarified that Eugene was absolutely rooted in Kansas City swing, and that his idol is Walter Page, the foremost bass player in the Basie band, and part of what became known as the All-American rhythm section – Jo Jones on drums, Page on bass, Freddie Green on guitar and Basie on piano.

Walter Page articulated rhythm in a way that was very hard driving, but never heavy or loud – it floated and skipped like marbles on a tambourine. The idea of Eugene’s Kansas City roots inside the Dave Brubeck Quartet might have seemed a contradiction in terms but it was the final ingredient that made the group cook. Wherever Dave went rhythmically there was always Wright’s bubbly bass sound underneath supporting him, and since Morello was a strong and assertive drummer, Eugene was the light within that relationship. During our conversation Eugene said that Dave had this great music in his head, and it was his responsibility to help get it out. Eugene was actually rather selfless. He was a fine soloist, but he saw that his fundamental role in the Quartet was to keep the mechanism going.

JJM . Brubeck wrote a document that he labeled “The DB Quartet – Principals [sic] and Aims” which, judging from its tone, had been prompted by frustration, either generally or by what Brubeck considered a particularly ineffective or lazy performance. Concerning the document, you wrote, “Part mission statement, part reaffirmation of some basic music principles, Brubeck’s words give the clearest insight yet on the inner workings of his quartet – how he expected, and needed to hear, polytonality and polyrhythms nurturing his music, and his irritation when musicians fell short.” What kind of a band leader was he? Was he tough to work for?

PC To clarify, that document is not dated but it does predate Morello and Wright, and was likely written during the time Joe Dodge was the drummer and Bob Bates – Norman Bates’ brother – was the bassist in the Quartet, probably around the time of the album Brubeck Time.

By the time I knew Dave he was into his seventies and he was everyone’s favorite jazz grandpa, a very genteel presence, but in some of the rehearsal tapes from that era you can hear that he doesn’t hide what he wants – he expected that his musicians wouldn’t just turn up and play the chords, he expected people to fully engage with his concept of jazz, and that meant, for instance, that everyone really had to understand the implications of polytonality. For example, if Dave was in the middle of a solo of a piece that was in B flat and he began playing a chord of G, the last thing the bass player ought to do was follow him into G – he had to stay in B flat, or else the polytonal tension would be lost. A lot of what that document does is lay out the bass player’s role, which was to keep the harmony going, but a few reviews of the book misunderstood that document as though showing that Dave was being doctrinaire and laying down unreasonable restrictions. But he wrote that document to allow that freedom to take root. Basic rules and understandings were set that would allow Dave and Paul more freedom to do what they wanted to do melodically and harmonically. The document provides an insight into the way Dave’s mind was working at the time, which was when they had just been signed to Columbia. We don’t know the context in which this was written, whether there had been a bad gig or he was just being generally fed up, but he lays it on the line. He was equally hard on himself – there was no sense of him ever allowing himself to coast and make things easier for himself.

.

A musical interlude…From We’re All Together Again For the First Time (1972), Brubeck (with Desmond, Gerry Mulligan, Alan Dawson and Jack Six) plays “Truth”

.

JJM . Brubeck was frustrated about the quality of his recordings, at one time writing, “I don’t think there has ever been an artist whose own studio recordings misrepresented his actual potential as much as mine.”

PC .That is from a letter he wrote to Steve Race, the British jazz journalist and pianist who wrote the liner notes to Time Out. You feel this in particular during the post-Time Out period, when the Brubeck Quartet became so popular that they were playing most every night, and in the midst of it were having to produce four or five albums a year. Dave lavished lots of care and attention on albums like Jazz Impressions of Eurasia, where every piece is carefully composed, and Dave Digs Disney and Time Out. But when you get to albums like Bossa Nova U.S.A. – which is stitched together from four or five sessions – there is a sense that those recordings were put out simply because people wanted a new Dave Brubeck record.

Also, as we talked about earlier, Dave had been signed by George Avakian but was then assigned to the producer Teo Macero and, although there were tensions, he was generally supportive of Dave. But Teo was completely wrapped up in the world of Miles Davis, more so than he was in Dave Brubeck’s world. It would have been better had Columbia followed the Dave Brubeck Quartet around night after night and recorded live concert music rather than the idea of putting together studio albums incredibly quickly, then presuming these albums would sell while the Quartet was on tour. You really get a sense of how this could have worked when you consider the 1963 Dave Brubeck at Carnegie Hall album, which I think is the greatest Brubeck album of all.

JJM .Is there an underrated or lesser-known album or individual piece you’d like to recommend?

PC One of my favorite Brubeck albums, For Iola, was recorded in 1984 on Concord – an utterly joyful album, with Bill Smith on clarinet, Chris Brubeck on bass, and Randy Jones on drums, and the music just sparkles and dances. A track that endlessly fascinates me from earlier is a piece called “Truth,” which Dave recorded on an album called We’re All Together Again For the First Time, which reunited Desmond with the saxophonist Brubeck worked with from 1968 – Gerry Mulligan. They toured as a quintet with Jack Six on bass and Alan Dawson on drums.

“Truth” begins with a propulsive vamp followed by an atonal explosion within the composition. Dave’s solo reflects that by starting with lines played in an incredibly nimble, fast jazz time, and after a chorus or two the left hand and right hand start moving away from each other as he moves into these extraordinary clusters, and any sense of regular meter or groove dissipates – it becomes a dialogue, really, between Dave and Alan Dawson. There are numerous points in the solo when you think that Dave is playing so many clusters so densely that he can’t possibly go any further; but he keeps on pushing and pushing and pushing, moving further and further out. The energy momentarily dips, then he spins the rhythm around, and rotates the energy in another direction.

Hearing this for the first time at age 14 blew my brain. Within a week or so I was listening to Edgard Varese, Stockhausen and Coltrane’s Ascension and Cecil Taylor – my interest in free jazz and modern composition began with this Brubeck track called “Truth.” Whenever I re-listen, I still find it an audacious piece of improvisation, particularly from a musician who was as popular as Dave Brubeck. It was recorded in Berlin presumably to a sold out house at the Berlin Philharmonie, which is a huge hall, and to think that Brubeck comes out and plays this to a crowd who were there presumably because they heard the original version of “Take Five.” I admire enormously how far he had developed as a musician and a thinker about musical structure and how he wanted the piano to sound. In that ongoing relationship in his work between atonality and tonality and polytonality, and the fact that his solos were often knitted together with different strands of these things tugging at each other, I always come back to “Truth” as a key moment.

.

___

.

“One of the reasons I believe in jazz is that the oneness of man can come through the rhythm of your heart. It’s the same anyplace in the world, that heartbeat. It’s the first thing you hear when you’re born — or before you’re born — and it’s the last thing you hear.”

-Dave Brubeck

.

.

photo courtesy of the John Bolger Collection/used by permission of the author

Dave Brubeck in the studio, during the Gone with the Wind sessions; April, 1959, Los Angeles.

.

.

Listen to the 1963 Carnegie Hall performance of “Take Five”

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time

by

Philip Clark

.

.

Click here to read the introduction to the book

.

.

___

.

.

Philip Clark is a music journalist who has written for many leading publications including The Wire, Gramophone, MOJO, Jazzwise, and The Spectator. He also writes for the Guardian, Financial Times, London Review of Books, and the Times Literary Supplement. He trained as a composer but these days prefers to produce his own sounds playing piano as part of a weekly free improvisation workshop. Clark lives in Oxford with his wife, two children, two cats, and more recorded music than he can ever listen to.

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Brubeck Collection, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library. .Copyright Dave Brubeck.

Dave Brubeck Poster; Poland, 1958

.

.

Searching for the Next Dave Brubeck

……………………………— Just You, Just Me

Traveling with a teen on a country road

leading us further into the future to her university

each local radio station blurting blue and dark tones

my daughter turns the dial like a tuning fork

till the next pop song sings of lost love and foul language

indescribable and profane electrically reproduced discord.

Thoughts wander over the wheel beyond wheat fields and hills

where music brought people together

even at times when politics ripped them apart.

I want to turn the car around

back to the piano, the bass, a real saxophone

orchestras full of color, with women and men,

but the tires keep pounding the pavement

in a discombobulated drum roll.

My young adult had already popped in ear pods

car games now only distant memories

of childhood so quickly forgotten.

Let’s take five with Dave, I tell her.

Who is Dave? she asks.

Who is Dave?

A jazz composer I got to see on stage before he died

Dave the oak root hands tap dancing across the keyboard

combining clarinet with upswing bass

the welder of classical and modern

innovative and traditional, patterns and pastels

improv’ with big band, harmony and melody

mixer of black and white and five in four.

The crowd wild with bone-gripping fervor

and muscle moving rhythm

the car now swaying and tapping to beat

my daughter air-playing the sax

I’ll pick up piano, she says,

our little mission searching for the new Dave

time-traveling war hero, joiner of styles, colors, ages

in troubling times, the next Dave

like taking five to be together

while my daughter is the young lion

off to her own den

and I the old tiger seeing her off.

.

by Julianne DiNenna

.

Julianne DiNenna writes from Switzerland and Italy. Her poems and short stories have appeared in: Months to Years; Adanna Literary Journal; Harbinger Asylum; Gyroscope Review; Italy, a Love Story; Susan B & Me; Grasslands Review; Unruly Women Writers (forthcoming), among others. She has won two literary prizes for poetry in Switzerland and was semi-finalist in BrickHouse Book’s Wicked Woman Book Prize.

.

.

_____

.

.

This interview took place on May 26, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

photos of Dave Brubeck from the John Bolger Collection published with the permission of the author

.

.

.