.

.

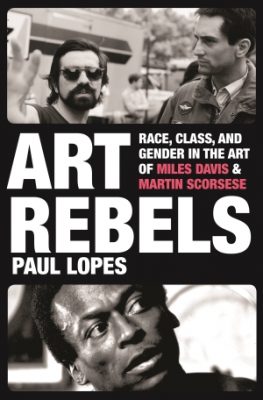

photo by Mark Diorio

Paul Lopes, author of Art Rebels: Race, Class, and the Gender in the Art of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese

.

___

.

…..Jazz legend Miles Davis and iconic filmmaker Martin Scorsese may not seem to have a lot in common, however, according to Paul Lopes, author of Art Rebels: Race, Class, and the Gender in the Art of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese, they both found success through a defiance of “prevailing conventions to elevate American jazz and film to unimagined critical heights.”

…..These artists came out of what Lopes defines as “The Heroic Age of American Art,” a postwar period of “effervescence of innovation and autonomy” that “created a situation where everyone recognized avant-garde and independent art.”

…..Of course, achieving success while defying tradition and remaining creatively independent is rare, but in Art Rebels, Lopes makes a compelling case for how Davis and Scorsese did so, and explores how their public stories and identities — each complex and often controversial — contributes to their immense appeal.

…..In an October 30, 2019 conversation with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, Lopes — associate professor of sociology at Colgate University — talks about how ethnicity, class and hypermasculinity impacted the work of these two visionary, independent artists.

.

.

___

.

.

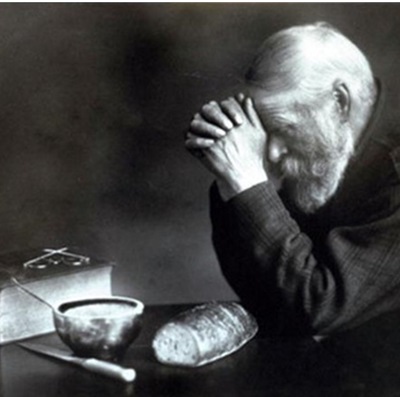

photo by Francis Wolff/© Mosaic Images

Miles Davis

“Miles Davis Quartet” session, Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, March 6, 1954

.

“Miles Davis is so compelling as a rebel artist during the Heroic Age of American Art and the modern jazz revolution in how he seemed to transverse, transgress, or hover over the distinctions that obsessed the jazz art world during his career. He constantly revealed the contradictions and ideological cul-de-sacs generated by these distinctions. He was a radical innovator who seemed to routinely return to the blues tradition as he moved modern jazz in new aesthetic directions. He was a self-proclaimed, and universally acknowledged, independent jazz musician who cared not one iota what critics or audiences thought of his music or on-stage persona, but he was an astute artist who was unquestionably the most commercially successful modern jazz musician of his time. And as a visionary of modern jazz who eventually incorporated the most radical of jazz practices, he also had a hold on the pulse of popular music practices. And finally, he was a race-conscious jazz musician committed to making race music who still worked with white musicians and incorporated elements of music making common among white musicians in jazz, rock, and classical music. What is remarkable is how Miles Davis brought these supposedly irreconcilable distinctions and irresolvable contradictions into a career in music making that created a coherent artistic repertoire possibly unmatched by any other American musician.”

-Paul Lopes

.

___

.

JJM How did you become interested in jazz music?

PL I picked up the alto saxophone when I was in elementary school, and then the oboe while in junior high. But I was always out of tune on the oboe, so I went back to the saxophone. My music teacher at Fremont High School in Sunnyvale, California, was a jazz musician himself, and quite a good saxophone player, so he was an inspiration for me. I played in the school’s jazz band and kept playing in college. And while in grad school at U.C. Berkeley, I played an occasional gig with jazz bands. Playing the sax became a kind of therapy for me. Playing my horn was a passion. Then, I took a graduate course at Berkeley called “Cultural Sociology,” and while reading the material I thought I should study the history and evolution of jazz. So, that led to my first book, The Rise of a Jazz World, and my new book as well.

JJM You write that your book Art Rebels “approaches the Heroic Age of American Art through music and film and two iconic artists in these fields, Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese.” What is the Heroic Age of American Art?

PL The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu was probably the most influential sociologist during the late 20th century. He was very interested in culture, particularly culture as a form of distinction. For example, he felt that people who like classical music usually occupy a different social class than people who like gospel music. So, their love of classical music, therefore, acts as a marker of their social class. But he was also very much interested in the autonomy and independence of art, particularly from commercial markets. So, he argued that in late 1800’s France there was this moment in art where the patronage that dominated the arts was rejected. Artists claimed independence from this patronage, which gave birth to the French avant-garde.

So, if you look, for example, at Impressionism – which was the first genre of modern art – it was created by artists in the 1860’s who said that they were not going to create works that the French Academy wanted. Instead, they were going to create their own art. So, they were the first of the avant-garde. At the same time, avant-garde theaters were emerging in Paris, and literature was also beginning to expand. So, Bourdieu calls this period a “heroic age” in European art, where the avant-garde and the idea of being autonomous from the market emerged, redefining what art was in Europe. Once Impressionist avant-garde art became a regular part of modern art, post-Impressionism artists like Van Gogh emerged to challenge the old avant-garde. So, there are these cycles of revolution in all the different arts as each generation claims its own autonomy against the old vanguard.

What I argue is that didn’t really happen in the United States at the same time because we didn’t have a real strong middle class, nor did we have a real strong art world until after World War II. In post-WW II, art began to be subsidized by the government and expanded at an exponential level, and many people chased the American Dream by going to college and moving into a growing middle class, so there was a sudden moment when the avant-garde arts could emerge. The new avant-garde included American Expressionism in painting, experimental music with the likes of John Cage, and the experimental film of Maya Deren. All these avant-garde arts were blooming, but at the same there was rock and roll, modern jazz, and eventually new Hollywood, so there was an effervescence of innovation and autonomy in the post war period that created a situation where everyone recognized avant-garde and independent art. Today, for example, everyone knows what “indie” means. If you had said “indie” in 1949, nobody would have known what you were talking about. So, it becomes part of what American art is. This is the era which I refer to as the “Heroic Age.”

JJM Simultaneous to this, changes in the culture industry were taking place, for example in technology and within the record industry and Hollywood…

PL Yes, that was very important. In the immediate post-war period, popular music was dominated by what I call the music oligopoly, which was a kind of collusion between radio, recording and Hollywood film. Hollywood really controlled the market because it owned about half of the music publishers in ASCAP. The oligopoly marginalized country music, and it marginalized race music. But that all fell apart when Hollywood lost its monopoly over movies with the Supreme Court decision that said Paramount can’t make films, own theaters, and also distribute films. So, they had to get rid of their theaters.

During the post-war period the government also issued a bunch of new radio licenses, which were backlogged due to the war but also because the FCC was pressured to not issue more licenses since the networks controlled radio at that point. But by 1948 and 1949 the networks were moving to television, so, who gives a hoot anymore about radio, right? Suddenly there is a doubling of the number of radio stations and they needed something to play, so they begin playing rock and roll, rhythm and blues, jazz, exposing this new and different music to people listening to the radio.

JJM Which opened the door for combative cultural politics as well…

PL Yes, that opened up in film, in music, and in a variety of other arts, and how you articulated that type of politics depended on the time period. It also diversified the type of music available on the mass market. This music clearly was available in small communities but this moment opened an avenue to reach a larger numbers of individuals.

In my previous book, The Rise of a Jazz Art World, I write about independent jazz record labels like Blue Note and Riverside and Fantasy, and without these indie labels, modern jazz would not have been successful – they were really essential to this transformation, as were the jazz critics who emerged at the time, as well as what I call the jazz enthusiasts, the jazz fans who frequented the clubs and supported this music.

So, as I say in my book Art Rebels, here is this moment where we suddenly have avant-garde or independent artists and genres appearing. What I wanted to do was pick two iconic artists that people intimately recognized as representing this revolution in American art during the heroic age, and who kept being at the forefront of their art. I love Miles Davis, and think he is one of the greatest modern jazz artists, and he kept doing it until he died in 1991. And, Miles was recognized as a great artist, regardless of the conflict over fusion music and other things. Martin Scorsese, as well, is still doing it today, the latest example being his film The Irishman. So I decided to pick these two artists and explore how the world of film and music perceived them. I call that the “public story” – the news coverage of these artists, what the critics wrote, what the artists said in their interviews, the documentaries about them, and their art itself. I ask, how did they frame their relationship to being independent artists in the market? The thing about both Martin Scorsese and Miles Davis – and I didn’t necessarily choose them for this – is that they were both incredibly commercially successful, which as you know in jazz in particular is very rare. It is very rare for a jazz musician, even during the modern jazz period, to make a lot of money. So, how did they navigate this world in which they were definitely successful in the market while also being seen as independent innovators? I cover that in the first part of the book. In the second part of the book I write about who they were. Miles was a middle-class black man from East St. Louis, and Martin as a working-class Italian from Little Italy in New York. How did their backgrounds influence their art, and how did it shape their identities as a black male and as an Italian-American male?

JJM What is Miles Davis’s role in the public story of modern jazz?

PL Well, as you know there are a variety of stories. In the first part of the book I write about his role in what I call “race music.” Guthrie Ramsey Jr. wrote a book called Race Music, which is basically about how urban black musicians refashion different black idioms into new “modern music” – for example, taking folk music and gospel music and transforming it into what Ramsey calls “race music.” So, within the world of professional black musicians Davis joined in the 1940s was a dream of creating a “Negro Music,” which was what older black musicians like James Reese Europe, Fletcher Henderson, and even Duke Ellington called it.

So, it was a Black Nationalist agenda – not radical, like the Black Nationalism in the 1960’s – but an idea that came from the Harlem Renaissance, that if we can create black art that is respected, it will lift up the entire community. This was an agenda that they constantly thought about. An example of this agenda is that an artist like Duke Ellington composed tone poems in the 1930’s about the black experience. Also, since black musicians felt that the white man controlled the music, they would rebel against them and reclaim jazz by creating bebop, a music they said – tongue in cheek, because it was a multi-racial movement – that a white musician couldn’t play.

Miles Davis, c. 1947

That’s an example of what was happening, and that’s where Miles Davis enters the scene. When he goes to New York City in the 1940’s he enters Julliard but the first thing he does is actually look for Charlie Parker, who he met earlier in St. Louis. He actually makes his first recordings with Parker. So, he kind of inhales the radical musical agenda among black musicians like Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and eventually Charles Mingus. He does that again in 1954 with his hard bop album “Walkin’.” This album marked a revolt of black musicians once again reclaiming jazz through a new genre called hard bop or soul jazz. And he continues to have that as part of his agenda. He doesn’t articulate it as strongly as Archie Shepp and others within the Black Music Movement of the 1960’s, but it was always a part of his sense as a black artist.

In the second part of Art Rebels, I write about him as a “race man,” because one of the things about Miles Davis that makes him an icon in the black community is that he talked about race relations from day one. He had no problem telling interviewers and others what he thought about America as a black man. That is part of why he was called the “dark prince of jazz.” He also got this from his reputation of not looking at the audience, being gruff, being aggressive, not being friendly, etc. The thing too about Miles Davis is that he was at the forefront of so many new genres of jazz — cool jazz, hard bop, modal, fusion. No one else was doing that.

JJM He had an ongoing commitment to innovation, which is of course a major part of his public story as a jazz artist.

PL Yes, and he would get snarky about it, particularly beginning with the fusion period, a time when people were saying he was destroying jazz. He frequently used the word “cliché.” He would tell people who wanted him to play “Walkin’” or “’Round Midnight” that he didn’t do that anymore. He complained that jazz fans just wanted to hear “cliché’s” and he didn’t play clichés anymore. He was always saying that in his interviews.

JJM You write that the news reports of Miles’ beating by the police in front of Birdland in 1959 “speaks succinctly to how deep the racial rift in jazz was by the end of the 1950s.” How did the reaction of white jazz critics to this beating expose this racial rift in jazz?

PL It didn’t dominate the news, but a quote from Downbeat hit me really hard. They reported this beating in the news section of the magazine, where they basically said, “by the way, we all know that Miles is a racist.” So, here he is, after having been nearly beaten to death, the first time Downbeat reports on it, this is what their reporter writes? As a sociologist who is discovering these things, I knew something was going on there. Along with Charles Mingus – who would yell at people in clubs – Miles seemed to represent to some white jazz critics this idea of the “angry black jazz musician.” So, I asked myself, “Why did he get this reputation?”

There was a general tension at this time, beginning about 1956 and 1957, when hard bop was taking the market by storm in terms of record sales and club dates, and black musicians were becoming more vocal about jazz being a “black music.” For example, Nat Adderley said he didn’t think anyone is better qualified only because of race, however, he said, “I do find certain inherent qualities that seem to be more natural to Negroes than white musicians.” Black musicians had an advantage because, as some would say, they knew gospel music, had “soul,” and so forth. So, these claims being made created a real tension, and this was even before Archie Shepp and LeRoi Jones entered the scene in the early 1960s. What is interesting about this tension is that the revolt by black musicians actually succeeds. By the mid-1960s, the covers of Downbeat and Metronome are being dominated by black musicians, which wasn’t the case in the 1950s, when most of the covers were of white musicians or singers. But by the mid-1960s, black musicians for the first time had taken center stage in the jazz art world. They were obviously always there, and often preferred by jazz fans, but if you look at Metronome or Downbeat of the 1950s, west coast jazz musicians with goatees were on their covers, and suddenly it’s all about cool jazz…

JJM Which is ironic because Miles was instrumental in launching cool jazz with Birth of the Cool, on which several brilliant white musicians played…

PL Yes, and while Miles is accused of being a racist, Gil Evans was basically one of his closest friends – Evans even named one of his sons after Miles. They loved each other. There were certainly moments when he only hired black musicians, but he also hired white musicians that he respected — Bill Evans on Kind of Blue is an important example. When he began playing fusion, some of the black nationalists accused him, basically, of playing “white” music.

JJM Another topic you effectively take up in your book is the idea of hypermasculinity. Miles had to push back not only against the jazz critics who felt he was selling out, but also those who seemed to characterize his music as being almost “feminine.” A common term used in reviews and biographies to describe his playing was “lyrical,” whereas Dizzy Gillespie’s was more “viral.” How did he respond to that?

PL I don’t have any indication of him directly responding to that, and usually these descriptions of his playing were meant in a positive way, anyway. It isn’t as if the critics calling his music “lyrical” were pointing out something bad about his playing, it was that he was unique.

So, part of the dynamic that I sensed, and other people have written on it as well, is the way in which masculinity was very much wrapped up in the jazz art world, and that included jazz critics. Masculinity was kind of tied up in the consumption of black jazz and black musicians – John Coltrane, for example, was described as “angry” and “virile,” which he denied. He was never an angry guy, but that’s what critics were projecting on to his music, and when they heard Miles Davis, in their imagination they are saying his music is kind of “lyrical.” I asked myself, where is that coming from?

That kind of discussion disappears by the late 1950s, but you see pictures of him boxing in an early 1960s Ebony magazine article, so it seems clear that at a personal level, too, masculinity was an issue for him. The question is, how did it articulate itself as part of Davis’ persona in the jazz art world? During the time he was playing fusion – a time when he was critiqued for trying to be a pop star – he was much more vocal, doing many more interviews beginning in 1969. And in these interviews, he was a lot more macho than he had ever been before. So, his effort to be a pop icon somehow got entangled with this type of performance of masculinity that wasn’t healthy for him and it certainly wasn’t healthy for women. And it persisted up to his 1989 autobiography, where he just basically unapologetically talked about violence towards women. I struggled with this because I felt as a white male scholar it was not my role to simply judge Miles Davis. So, I read as much as I could of black sociologists and other black critics – both male and female – to see how they negotiated this. And what is wonderful about this story is how the black community confronted this. It was ignored in certain ways, but black intellectuals did try to deal with it, and they continue to deal with it today. While white critics were upset with the autobiography, that part of the story, his misogyny, kind of disappeared. There are three books, for example, that were recently published within the last five years or so on the history of “cool.” And, all three white male authors begin their books with Miles Davis – for a reason, he is “Mr. Cool” – but the authors don’t mention that aspect of who he was at all. Nor do the authors address what his misogyny as “Mr. Cool” possibly says about the history of “cool.” I find that very interesting, and I mention that at the end of my book.

JJM You quote the noted musicologist and author John Szwed – who is one of Miles Davis’ biographers – as saying that Miles “offered whites and blacks entrée to what they took to be a certain kind of blackness.”

PL Definitely, and what is interesting is how Miles resonated for both the black community and white community and black artists and white artists. There are several quotes in my book by black artists talking about how he meant everything to them. Some of them also grappled with his misogyny. In 1985, Amiri Baraka wrote that “for many years of my life, Miles Davis was my culture hero; artist, cool man, bad dude, hipster, clear as daylight and funky as revelation,” and that he was “not only the cool hipster of my be-bop youth, but also the embodiment of a black attitude that had grown steadily more ubiquitous in the 1950s – defiance.” Miles was also worshipped by white audiences and white musicians. He was one of those individuals that kind of stood above us to a certain extent, so his fall with the scandal of the autobiography was quite shocking, because for many he was on this pedestal.

JJM The whole notion of the way he treated women and his admission to hitting women has always been deeply disturbing. You wrote, “What stood out was his abuse of and violence against women closest to him,” which is always shocking…

PL And what was most shocking for people too was that he was unapologetic about it.

JJM Staying on this topic of masculinity, but shifting to a conversation on Martin Scorsese, you write quite a bit in the book about how characters in a Scorsese film are so outwardly masculine. For example, you write that the boxer Jake La Motta – Robert DeNiro’s character in Raging Bull — was a violent, hypermasculine male with an “uncontrollable jealousy and violent behavior out of the ring toward women and men.” Hypermasculinity is an important characteristic of actors’ roles in many of his films…

PL Yes, these characters are dealing with their masculinity, which men do, right? It is important to realize that I am implicated in this book as much as anyone else. My relationship to black jazz musicians is just as implicated as Dave Brubeck’s or Stan Getz’s or whoever, right? It’s the same way with Martin Scorsese. But it is interesting that he keeps returning to these hypermasculine characters – who in most of his films are also the protagonists – enough so that he seems obsessed about it. And, as is the case with Raging Bull, this hypermasculinity either ends in tragedy or some kind of redemption. With La Motta, there is a type of redemption. Scorsese even quotes from the Bible at the end of the film to emphasize this final redemption. This redemption is a way of identifying with this character. He is not a nice guy in the film, so there is no critique there on my part. And there is no reason why you can’t be sympathetic to an individual like La Motta. But why is redemption the main arc of the story?

I also write about how in some ways it’s about the tragedy of being a working-class Italian male, where your only choices are the boxing ring, the Mafia, or being a priest, which is a line that Scorsese said all the time. He comes back to this in Cape Fear, Good Fellas, and Casino – and it’s not as if these characters don’t exist in real life, because they do — but Scorsese seems to be obsessed with it. When Cape Fear came out, Scorsese actually talked about how he, and DeNiro, identified with the hypermasculine characters in Scorsese’s films, and about how they wanted to explore the different angles of understanding their hypermasculinty. While I saw this in their films, my interpretation is also based on the public record, it comes from critics and people talking about these films and their hypermasculine characters. So that is why I am picking this discussion about hypermasculinity up, because it has been a part of Scorsese’s public story from Mean Streets up to his latest film The Irishman.

JJM Scorsese’s public story is rooted in Little Italy but, as you point out in the book, he was able to move his story from being just about an Italian American experience to also include the history of the Irish and other white ethnic peoples. So, much of our conversation about Miles centered on race, and with Scorsese, it is an immigrant’s story – how they fit into America and how crime and religious tradition is a big part of it…

PL Right. He begins by being an unmeltable Italian American. What really struck me is that even in the early 1970s, before he had really even done anything, there was a conference on Scorsese, which was all about being an Italian American. Many of his interviews at that time talk about his being Italian, so this was very important to him, and it was important to other Italian Americans as well. Historians and sociologists note the late 1960s as a period for ethnic revival, where white ethnics rediscovered their roots and celebrated them in the post-war period. So, he was very much wrapped up in that in a particular way.

The Italian American experience is not the same as the Irish American experience, so he grapples with that difference, but what is interesting is by the turn of the century, with his film Gangs of New York, he begins to see that his Italian American identity is linked to the Irish American identity, to Jewish American identity, and what we call “White Ethnic” identity. And that is happening in America more generally, so his films reflect the evolution of this identity. So there is this hyphen-nationalism that shows up in his films, as well as in interviews where Scorsese was saying that the Irish and eastern and southern European immigrants who came to America in the late 1800s and early 1900s were the ones who built America – they built New York City, Five Points, Little Italy. The American experience is less about Plymouth Rock and a lot more about Ellis Island, and that is what hyphen-nationalism is. It is these new immigrants who really made America “great.” And, I didn’t go looking for this, I had not studied Martin Scorsese – I had seen his films, and loved them, and he is one of my favorite directors of all time – but when I started doing my work I found that this was a central theme in how he has defined himself as a filmmaker. He even did a documentary on Ellis Island.

JJM So, when you look back on the careers and public stories of people like Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese, it helps us understand who we are today…

PL Yes. When people study art, whether it is literature or film or music, they tend to look at the content of the art itself. What does Scorsese’s Cape Fear say? What does the music on Bitches Brew tell us? Or what does a 1969 Miles Davis stage performance say? I focus on the conversations that film critics, jazz critics, journalists, museum curators, documentary filmmakers, and others have about art and the artists who make it. This is the public story of an art world and its artists, and this story tends to bring in larger issues, so it becomes an important place to talk about things like gender or race or politics.

We can see that today, when, for example, people talk about the film Black Panther. They are not just talking about the film, they are also talking about what the film’s story says about America today. Because it says something, right? And then, within that film review you can talk about things like the state of the African American community in Oakland, California, where some of the film takes place. That is what happened with Miles Davis. That is what happened with Martin Scorsese. And, I would argue that some artists engage this type of cultural politics more than others. We know, for example, that when Kanye West opens his mouth, people talk about what he says. The same with Kendrick Lamar or Beyonce. They understand that it is not just their music that says something, but that their music triggers a conversation. That is what I find fascinating, that art becomes a vehicle for us to talk about other things.

.

.

___

.

.

Art Rebels: Race, Class, and the Gender in the Art of Miles Davis and Martin Scorsese

by Paul Lopes

.

.

Paul Lopes is associate professor of sociology at Colgate University. He is the author of Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book and The Rise of a Jazz Art World

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on October 30, 2019, and was produced and published by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita

.

.

Francis Wolff images courtesy Mosaic Images

Miles Davis illustration courtesy Martel Chapman

Book jacket image courtesy Princeton University Press

.

.

.

Thanks for this interesting interview, Joe. Lots to think about.