..

.

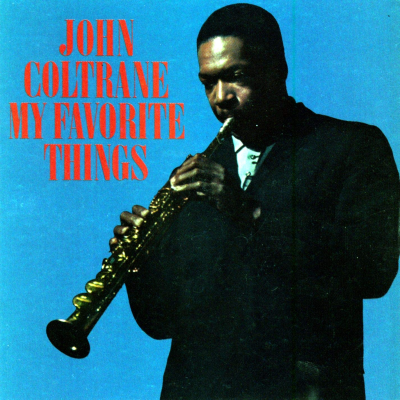

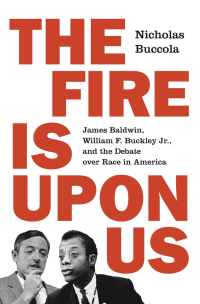

photo Princeton University Press

Nicholas Buccola, author of The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America (Princeton University Press)

.

.

___

.

.

…..In his 1962 essay “Down at the Cross,” James Baldwin wrote quite hopefully; “If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.”

…..Fifty-eight years later, in spite of the good work and hopes of many along the way, the “racial nightmare” has not ended. It seems racism has an enduring shelf life. While there are new characters, the same tired, dreadful and horrific plot is performed.

…..So history is repeating itself, but as we know, understanding history may also be how we can “change the history of the world.”

…..In The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America, author Nicholas Buccola tells the story of the historic 1965 Cambridge Union debate between Baldwin, the leading literary voice of the civil rights movement, and Buckley, a staunch opponent of the movement and founder in 1955 of the conservative publication National Review. The evening’s debate topic? “The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro.”

…..While Buccola devotes much of his effort to telling the story of the debate itself, he also provides the reader with an excellent understanding of Baldwin and Buckley’s radically different backgrounds, the events leading to the event at Cambridge, and, most importantly, reminds us of how their stark philosophical differences and verbal sparring over the years continues to inform America’s current racial divide. Much of their intelligence has been lost in today’s “debate” over race, but the similarities of the arguments are striking. Buckley was determined to expose Baldwin as an “eloquent menace,” while Baldwin felt Buckley was delusional, whose popularity revealed the sickness of the American soul.

…..This is an important, riveting, and compelling book, one that Eddie Glaude, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, and author of Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own says “brilliantly describes our current malaise,” and calls it a “must-read – especially as we are forced to choose between competing visions of who we take ourselves to be as Americans.”

…..Buccola discusses his book in a July 23, 2020 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita.

.

.

___

.

.

|

photo by Allan Warren / CC BY-SA James Baldwin in London’s Hyde Park, 1969 |

SPC 5 Bert Goulait/Public domain

|

.

.

…..“James Baldwin was second in international prominence only to Martin Luther King Jr. as the voice of the black freedom struggle…Baldwin had established himself as one of the [civil rights] movement’s leading champions, and Buckley was known to be one of its most vociferous critics, but [Cambridge] Union officials hoped the motion [‘The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro’] would inspire [Baldwin and Buckley] to engage more fundamental questions about the relationship between the ideals of the American dream – for example, freedom, equality, and opportunity – and what Baldwin had called ‘the racial nightmare’ that was tearing the country apart. In a sense, this was the perfect motion for Baldwin and Buckley to debate. The core of Baldwin’s indictment of his compatriots was that their mythology – including the American dream – had enabled them to avoid coming to terms with the injustice of their past and present. Unless they could accept the truth of their past and take responsibility for it in the present, Baldwin argued, the American dream would remain a nightmare for many.

…..“Buckley, on the other hand, considered himself to be a guardian of the ideals at the core of the American dream. The American experiment had been, he thought, a tremendous success, and the ‘responsibility of leadership’ fell to elites like him to protect the ideas, norms, and institutions that had made it so. The United States, he believed, had become an ‘oasis’ of freedom and prosperity’ because it was a society rooted in certain ‘immutable truths.’ Among these truths were the belief that the ‘rights and responsibilities of self-government’ ought to be entrusted to those who had demonstrated themselves worthy of power and the idea that ‘security’ – in a social and economic sense – should be ‘individually earned,’ not provided by the government.”

-Nicholas Buccola

.

.

As a prelude to the interview, you may enjoy watching a nine-minute PBS News discussion with Nicholas Buccola about this book

.

.

JJM What is your background, Nick?

NB I was born in the San Fernando Valley and spent most of my childhood in Ventura County, north of Los Angeles. I went to Santa Clara University, where I did my undergrad work, studying political science and philosophy. After I graduated I returned home to work during my gap year in local politics, and then went to grad school at the University of Southern California, where my plan was to study Constitutional Law and Supreme Court politics. For a variety of reasons, though, I instead became interested in American political thought in a serious way, and that became the focus of my studies. After graduating I came to Linfield College in McMinnville, where I have worked since 2007.

JJM Your title is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science. Interesting time to be a political scientist…

NB Absolutely. There’s always plenty to talk about. Most of what I teach deals with history, which gives me the ability to have some crucial distance from the headlines, but the headlines are always there and always relevant to what we are going through as a society, and I like being able to talk it through with young folks trying to work things out.

JJM In your book’s prologue, you wrote; “This book is about far more than the debate itself. Baldwin and Buckley were almost exact contemporaries, and so they came of age – intellectually speaking – at the same time (the late 1940’s) and reached the height of their prominence at nearly the same moment (the mid-1960’s). Right in the middle of that timeline, the two movements that each man would do so much to shape – the civil rights movement and conservative movement, respectively – were born. This is the story of how two of the most consequential postwar American intellectuals responded to the civil rights revolution.” What inspired you to tell this story?

NB A few years ago I was invited to write an essay about Baldwin, who I had read a little bit over the years but never very seriously. I confessed this to the editor, who told me that since the essay wasn’t due for two years I could spend a year reading him and then another year writing the essay. That sounded very reasonable, and once I accepted and began reading Baldwin in a serious way, I was hooked.

In that process of getting to know him, I came across the BBC film of his debate with William F. Buckley, which I was aware of because Ta-Nehisi Coates had written a piece on it for the Atlantic and the video had gone viral. Once I watched the debate I was transfixed by this dramatic moment featuring these two radically different characters in the time of the civil rights movement. I became obsessed with the debate from that point forward, and began thinking about using it as the framing device for the essay. At one point I was talking with a friend about this work and told him I felt there was enough in this to write a book. During the conversation I learned that a book had just come out about Malcolm X and his time at Oxford, which got me to thinking that my project would be a short book on Baldwin at Cambridge.

The Baldwin Papers hadn’t opened yet, so I did a deep dive into the Buckley Papers at Yale and read lots of material from both of them, and in doing so it became pretty clear that there was a bigger story to tell. There was of course the story of the night of the debate itself, and I worked on figuring out how they got there and who invited them, which led me to try to find the Cambridge students who hosted them fifty years ago. With the help of my wonderful students at Linfield, we set out on a kind of detective story to find these guys, which was quite interesting, and allowed me to reconstruct the night of the debate.

As I began digging into the archival research, it became clear to me that this really isn’t a small book solely about the debate, this is a big book about these two men and the years leading up to it that could give readers a sense of their minds and how their experiences and thinking about important issues evolved over time.

I began writing the book in January, 2016, and while the story of race in American politics is always relevant, it was becoming more so as a result of the rise of Trump, which made people pay more attention to these issues in the broader culture more urgently, and provided some of the fuel for me as a writer to tell this story.

JJM What set Buckley on a collision course with Baldwin?

NB That is a theme I come back to frequently in the book. In some ways it goes back all the way to their childhood homes. All of us are shaped in many ways by the things we learn from the cradle, and Buckley was exposed to a deeply hierarchical world in which he was taught that some people are fit to rule, and others are fit to be ruled, and the Buckley family is among those who are fit to rule. That belief in hierarchy and that suspicion of democracy and any form of egalitarianism was thoroughly racialized in his household. I write in the book about how the Buckley children acknowledged that their parents were racist by just about any definition, but that they were taught from a very young age a particular kind of belief in racial hierarchy that was rooted in a sense of noblesse oblige, where those in a superior position had an obligation to take care of those beneath them. This sticks with Buckley throughout his life.

He always thought of his own views on race as a little more progressive than his parents in certain ways. For example, his parents are pretty clear that their belief in racial hierarchy was based on their thinking they possessed a biological, racial superiority. Buckley seems to have shed that view, but he sticks to the view that racial politics is rooted in hierarchy, and believed that there is a difference between the kind of racism that his parents practiced and a racism that is rooted in animus. So he always had that kind of paternalistic attitude on racial questions – which goes with him as he develops intellectually – and you can see it manifesting itself when he is put into the position of having to figure it out as a public intellectual and a builder of the conservative movement. At the time of the founding of the National Review, he was having to consider how conservatives should respond to the issues of race and civil rights as issues are intensifying – issues like the Brown vs. Board of Education desegregation decision, and the arrest of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott.

The first issue of National Review, November 19, 1955

In that moment Buckley was only in his late twenties, but he’s becoming an important figure in the conservative movement, and it doesn’t take much deliberation for him to decide that conservatives ought to be in a position of what he considered to be a non-racist resistance to the civil rights revolution. He wanted the National Review to be non-racist, but not reflexively racial-egalitarian, and the outcome of that was a hostility to any federal intervention that promoted desegregation – hostility to the Freedom Riders, hostility to the sit-in protests, and hostility to Martin Luther King. The one exception is that Buckley and his crew at National Review were mostly okay with economic boycotts, but that was the only thing they were willing to defend. Buckley ends up being against the Civil Rights Act, against the Voting Rights Act, and he takes this position of opposition at almost every turn, so in many ways his thinking about these issues put him on a collision course with Baldwin.

One more thing about this is that it’s not just that Buckley took these positions of resistance therefore it was fated that Baldwin would square off with him, but it’s also that, from Baldwin’s perspective, Buckley occupied an important space, and Baldwin argued that many people are caught up in the web of the politics of white supremacy, and thought of a lot of people as essentially being raised in a such a particular sense of reality that they couldn’t imagine anything otherwise.

Somebody like Buckley was in a different category for Baldwin, because while it is certainly true that Buckley and all human beings involved in this perspective are caught in a sense of reality we don’t really understand, there is something about Buckley and the class he represents that Baldwin thought was especially nefarious because Buckley knew that there were alternatives to the kind of racial politics he was promoting. That is a powerful part of this story, that Baldwin gives us this lens through which to view what Buckley was up to, and in many ways revealed the moral shortcomings of his position.

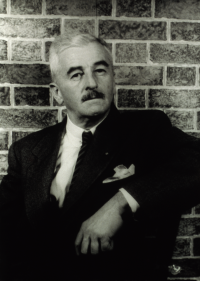

William Faulkner, 1954

JJM The author William Faulkner was a catalyst for their paths converging…

NB Yes. The major approach I take in this book is to weave these two stories and capture the ways in which the they think about these issues, and Faulkner plays an important role in this because it is one of the first moments in the book when you have Baldwin and Buckley coming together as they are thinking about something in common.

While there were times he was critical of Faulkner’s work, Baldwin admired him greatly as an artist. He reflected on Faulkner in print in a serious way in the mid-1950’s, after Faulkner gave a couple of interviews in which he articulated what he called a “middle-of-the-road position” on the developing situation of civil rights, and confesses that while the southern position of resistance is morally indefensible, he believed that it was necessary to go slow and not take either extreme position.

He sets his extremes as on one side being the individuals on the White Citizens Council who take a position of intransigence on civil rights, and on the other side are groups like the NAACP. Faulkner sees himself as being somewhere in between these two groups and says quite disturbingly that although he concedes that there is a strong moral case for integration, he would be willing to go into the streets and shoot “federal agents and Negroes” in defense of the South’s right to govern itself and of its traditions.

The editor of the Partisan Review subsequently invites Baldwin to write a response to Faulkner, which is an ingenious invitation. At that point, Baldwin is in Europe but is feeling this draw to come back to the United States and engage more directly in the civil rights struggle. A short piece he wrote called “Faulkner Desegregation” was a way to for him to reflect about the southern mind. He had not even visited the American South when he wrote this so he’s doing it in an abstract way, but he felt that while it is easy to dismiss Faulkner, it is very important to take him seriously and to try to get inside his mind and see the world as he sees it so we can better understand the resistance that is happening in the country.

In the first line of the essay Baldwin takes an empathic tone and says that we have to recognize that any change is a kind of death, and to see that people in the South view this change as upsetting and terrifying. While he believes that fear is at the heart of so much of this resistance, as he works his way through the essay he ultimately says that Faulker’s position is insane because he is holding on to two legends that are fundamentally incompatible – the human quest for freedom, but freedom for African American people can’t be recognized. These were two things that Baldwin said can’t coexist forever. What Faulkner was asking for is more time, but as Baldwin asks later in the debate with Buckley, how much more time do you want? You’ve had hundreds of years and we can’t wait any longer. And that diagnosis of Faulkner has relevance for how Baldwin views Buckley, because at that same moment in the National Review Buckley is calling Faulkner a voice of sanity, saying that this is not about morality, this is about politics, and ultimately southerners like Faulkner are embracing a kind of political realism that requires this issue to be addressed gradually, and not in the way the Supreme Court and the civil rights activists are addressing it. So, in this issue they are both engaging in, you can see how Baldwin and Buckley are thinking in radically different ways.

JJM How did Buckley and the writers at National Review respond to the civil rights movement?

NB The National Review‘s position on the civil rights movement ranged from skepticism to hostility at just about every turn, but they rationalized that resistance in a few different ways. One is that they offered an argument that was rooted in the Constitution’s separation of powers, arguing that no matter what anyone thinks of civil rights morally, we are constrained in how we respond to it based on the division of power both horizontally within the federal government, and vertically within the powers of the states and localities. This jurisprudential argument justified what they called decentralization, a central safeguard of the Constitution that needed to be respected even if we did not like the results that it led to regarding the question of civil rights. At the end of the book I write that this Constitutionalism argument doesn’t seem to have mattered as much to Buckley as he claimed, which I point out through some of his writings.

They also had a “Southern way of life” traditionalist argument which Buckley writes a little about himself, but he also relies on other National Review writers who offer a philosophical and sophisticated defense of everything his mother taught him about race; that, yes, there is a racial hierarchy that is dominant in the South and elsewhere in the country, but that racial hierarchy is ultimately a benevolent hierarchy with “fruitful inequalities,” which was a very important idea for Buckley.

They also made arguments that were rooted in authoritarianism. For example, they felt that the number one priority for any society is to provide social order, and the civil rights movement is upsetting order. Buckley would sometimes claim to be a Libertarian but his libertarian-ism definitely had its limits, and he would ultimately say that arguments about going slow on civil rights could be rooted in an argument for order.

In Buckley’s essay “The South Must Prevail,” he provides a combination of these arguments along with a paternalistic argument rooted in a claim that white people, at least for the time being, are the “advanced race.” That piece is very powerful because it is written in the midst of the debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1957, and it defended an amendment to that act which more or less said that any accusation against southern officials violating the civil rights of African-Americans in the South will be decided by juries, not by federal judges. This amendment was put in by southern segregationists like Strom Thurmond for the express purpose of hollowing out the entire act of just about any meaning. The idea of government officials interposing themselves between the federal government and the people when they don’t like what the government wants them to do goes way back in our history. Jury nullification takes the argument back even further. They are basically saying, go ahead and pass your law, our all-white juries are not going to enforce it, which in essence nullifies the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Buckley writes his essay defending the idea that white southerners are entitled to do this, but they have a duty to do this because they are, for the time being, the “advanced race.” So, that’s a little bit about how they rationalized their resistance.

JJM Yes, you write that Buckley said that “it is more important for any community in the world to affirm and live by civilized standards than to bow to the demands of the numerical majority.” What also mattered to Buckley was who had the power, which was more important than who had the truth, and felt an obligation to serve as guardian of the “known goods” against the progressives and revolutionaries who promise to deliver “unknown betters.” How did Buckley’s understanding of the relationship between power and truth impact his views on civil rights?

NB I’m a political theorist, so I have spent my life grappling with these big questions about politics. What is justice? What is freedom? What is the proper role of government? In many ways this book is a departure from traditional political theory – it is a much more narrative-driven book – but the question you raise is a thorny political theory question, and it is at the heart of making sense out of what Buckley is thinking regarding civil rights. It is one of those paradoxes that I find with Buckley and others on the American right.

The founding documents of the National Review say that they are against relativism, that they believe in an absolute and immutable truth, whether it’s natural law, or even divine law, as opposed to those who believe truth is culturally relative or relative to whatever happens in the voting booth. This is a central pillar of conservative philosophy. One of these fixed truths is the inviolability of the dignity of the individual, whether it’s an argument that the individual was created in the image of God, or some philosophy of natural law or natural rights. While they claim this to be a central guiding principle of their philosophy, time and again – especially in the question of civil rights – we see that in practice that doesn’t seem to be their operating philosophy.

This comes up prior to their engagement with civil rights. In the context of McCarthyism and also in the context of Buckley’s views of academic freedom, he seems to be philosophically absolutist but operationally relativist. So, when it comes down to the issue of civil rights, he is willing to say that this isn’t really about morality, nor is it really about the inviolability of the individual – this is about realpolitik, this is about the very difficult issues confronting southern officials, and we can’t rely on philosophical abstractions, and we can’t rely on “highfalutin language.” He says in “Why the South Must Prevail” that this is not a question that will be resolved by an appeal to the rights of the born-equal individual; when it comes down to it what matters in the South is that those who have power are using it responsibly in order to protect civilization, an idea that was always vaguely defined. That ends up being the core of Buckley’s argument, which is a little slippery. What does that mean for absolute truth? That is an important question for us to grapple with as citizens because it comes back at us time and again in different contexts.

JJM Did Baldwin view segregation in the North any different than segregation in the South?

NB One of the few things that Baldwin and Buckley have in common is they are both critics of northern hypocrisy on race, but they take this position for very different reasons. Buckley is taking that position to try and convince northerners to lay off the South, and Baldwin does so to try and convince northerners that they need to lay into themselves and not feel as if they are beyond reproach.

James Baldwin, 1969

This is something that is crucial for Baldwin, who is always so good at drawing on his own experiences and reflecting on what they mean in a more universal sense. He was a child of the mass migration of African-Americans from the South to the North – his mother comes north from Maryland, and his stepfather David comes to New York from Louisiana – and he describes this in his novel Go Tell It On the Mountain and in some of his essays. As they flee one kind of terror, they are introduced to another, that the Jim Crow-ism of the North is more subtle than the racism of the South, but it is no less deadly. He even says that there is actually something more sinister about northern racism because even though navigating the boundaries of the South are perilous, those boundaries are straightforward and clear, while the kind of racism one experiences in the North is a little more opaque and in some ways more treacherous.

What is absolutely crucial to know about Baldwin is that he could be hard on northern liberals who felt a moral superiority, and who he felt participated every day in the structures of power that are central to the racial nightmare we have in this country. He didn’t want to let anyone off the hook, he was always there to remind every one of us of the ways are complicit in racial injustice.

JJM Meanwhile, Buckley was speaking of this racial hypocrisy of the northern liberal in order to get people to lay off the South…

NB Absolutely. Part of what he is doing is to ask the northern liberals – who are more than willing to be indignant about the racial politics of the South – to see the ways in which they are participating in racial hierarchy in their own backyard, be willing to acknowledge it, and then ask themselves why, in many cases, they are hesitant to take action to rectify this injustice. Part of his argument is that if they are willing to engage in that reflection, while they may not connect to the southerner and some of their actions resisting Black liberation, they may have more sympathy and understanding for those who are feeling threatened by it.

It is important to understand how Buckley is thinking through these issues because that thought process is still very much with us today, and it manifests itself almost identically to the ways Buckley argued these positions sixty years ago. In many ways, we remain stuck in that same cycle.

.

A video interlude…James Baldwin makes his opening argument during the debate

.

.

JJM The debate itself – held at England’s Cambridge University on February 18, 1965 – is gripping (and readers can view it at the conclusion of this interview). The debate’s motion was “The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” How was this debate put together, and how was this motion arrived at?

NB One of the fascinating things about writing this book is that during the early research I was able to interview organizers of and eyewitnesses to the debate. This debate came about almost by accident. Baldwin was going to be traveling through the UK to promote the paperback release of his third novel, Another Country, so his publicist there reached out to various venues in and around London to schedule a week-long publicity campaign. One of those he contacted was Cambridge Union, one of the world’s most prestigious academic institutions that had just celebrated its 150th year in existence. It is predominantly a student debating society, and one of the things they would do on occasion was to have students debate alongside guests of distinction – for example, politicians, intellectuals, and artists who could speak with authority to the question before them.

In January, Baldwin’s publicist contacts Peter Fullerton, a Cambridge undergraduate student who was president of the debating society at the time, and asks if Baldwin – then one of the most famous authors in the world – could come to Cambridge for an author event. Fullerton said that as a debating society they would be happy to host Baldwin, but only if he’d be willing to debate a theme related to his writing. The publicist went back to Baldwin with this proposal, and he agrees in principal to do it without knowing who or what he’ll be debating, and they work out these details over the course of only a few weeks.

As president of the union society, Fullerton had to come up with a motion for Baldwin to debate, and to find an opponent for him to debate. While it was fifty years later and he couldn’t recall all the details, Fullerton told me that at the time he had some familiarity with Baldwin’s work, and I posit in the book that inspiration for the motion the union came up with, “The American dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” may have been from some very bracing passages about the “American Dream” within Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, his 1963 best seller that had shot his celebrity status to the highest possible level.

The other important contextual factor is that Fullerton wanted to come up with a motion that someone from the other side of Baldwin could debate. At that time, 1965, the Civil Rights Act had passed and there had been so many triumphs within the civil rights movement, but Fullerton was looking for something more nuanced than a simple “yea” or “nay” debate on civil rights. Buckley said later that he would have refused to participate in such a debate, which is interesting given what we know about his record on civil rights leading up to the debate. While he was not internationally known at the time, Buckley was sought after as Baldwin’s debate opponent because he was second only to Barry Goldwater as a prominent face of conservatism.

There are a lot of back stories to setting up the debate, which I go into detail in the book, and there are many reasons why it shouldn’t have happened, but it did, which is a good thing because it ends up being a very important moment in the struggle for civil rights and Black liberation.

JJM The debate is filled with dramatic moments, one of which is when Buckley said, near the outset of his remarks, that it was “impossible to deal with Mister Baldwin unless one is prepared to deal with him as a white man.” What was Buckley’s intent with that statement?

NB Buckley had listened to the student debaters prior to Baldwin speak, and after seeing the students’ reaction to Baldwin – who spoke before him – he said later that he knew it wasn’t going to be his night, so rather than soften his views to try to win a few more votes he decided to go for the jugular. So he starts with this idea that the only way to treat Baldwin with respect is to treat him “as if he were a white man.”

Buckley was very influenced by Gary Wills, who had written a review of The Fire Next Time for National Review a couple years prior, and one of the review’s themes that Buckley awkwardly attempts to utilize is that Baldwin has been spared the kind of criticism he deserves because of the color of his skin. He is essentially saying that the most insulting thing Baldwin has experienced is that white people have refused to take his arguments seriously enough to challenge him over them. So when Buckley says he’s going to treat Baldwin with the respect that he would give to a white man, he is saying he is willing to take his arguments seriously, and by challenging them he is actually doing a service to Baldwin.

This is a crucial moment in terms of understanding where Buckley is coming from – that he feels he is one of the only people in the chamber who is actually treating Baldwin seriously and with respect. For years after the debate, Buckley refused to accept the idea that Baldwin had superior arguments to him, and in fact he felt that all those votes Baldwin got in the chamber that night – the final tally was 544-164 in favor of Baldwin – came from people who were not taking Baldwin seriously.

JJM Right, they only voted for Baldwin because he was Black…

NB Yes, and Buckley would write in one of his later pieces about the debate that it was a planned “orgy of anti-Americanism,” and that the students voted for Baldwin to affirm his identity, not his arguments. Later, in the 1980’s, he said that because Baldwin was Black, homosexual, anti-American, and a religious skeptic, the audience was sympathetic to him that night. One of the things I find most striking about that is that as we continue to have debates today about “identity politics,” and while argumentatively what Buckley is saying is extremely important to think about and engage in a serious way, we seem to still be stuck in that kind of back-and-forth, where we refuse to acknowledge the arguments and avoid the central issue.

.

A video interlude…James Baldwin speaks to the reasons why Black people are “in the streets” in 1967

.

JJM Concerning white police, Baldwin wanted people to think about the “well-meaning white policeman who has been charged with the task of law enforcement in black neighborhoods. What must it be like for him to face, daily and nightly, people who would gladly see him dead?” What suggestions did Baldwin have for the complexity of policing during the 50’s and 60’s?

NB Well, that is obviously an important question, especially now. Baldwin’s thoughts on this are powerful because he wasn’t someone who would provide a detailed policy proposal about an issue like this, but one of the things that he does extraordinarily well is invite us to think about things in a slightly different way than we had been.

When it comes to the subject of policing, he is there to remind us to think structurally and to get beyond seeing them as manifestations of old arguments. For example, Baldwin would push back against the “few bad apples in the police department” argument and would instead ask us think about the broader structural question of who has power and who doesn’t, which is at the foundation of our trouble.

Two things Baldwin asks us to think about regarding this question are economics and identity, and he wants us to grapple with the question of why is it that people are subjected to police surveillance, harassment, and brutality at such a higher rate depending on their racial and economic background? In many of his pieces dealing with the history of the United States, or the struggle for civil rights, he asks the white readers to travel with him in their imaginations to a place like Harlem, for example, and ask yourselves two questions; “Would I want to live here?”; and “Why don’t the people who live here move somewhere else?” He felt if readers were to ask those two questions it would help make sense of this other question often asked of him by white folks, which is “What do Black people want?” And Baldwin would often ask back, “What do you want?” which is a very simple, very profound question to ask ourselves. He felt that in order to make sense of both urban unrest and the broader questions of policing we need to grapple with the reality that in virtually every American city we are seeing borders established – what he calls “occupied territory” – marked by police officers who are not evil human beings intent on creating terror, but who are there to maintain systems that are established at much higher levels than the officer on the street.

So, as in the example you used, Baldwin would write these messages of empathy, talking about what it must be like to be a rookie cop working within this “occupied territory,” knowing that those around you would like to kill you. He says that a part of this is related to these questions about the economic structures of power within our society, and questions of consciousness and identity. For example, why is that that it is within our constitution, and who we consider ourselves to be, that we allow these kinds of occupied spaces to continue to exist and persist, and why are we unable as a society to challenge these structures of power? He felt that part of the explanation is economic, but part of it is also about consciousness and identity – that we are able to construct identities allowing us to resist coming to terms with the reality that we’ve created, which is horrifying when we are willing to look at it in an honest way. So, Baldwin wants us to think about these big structural questions. At this moment in time, more than most other times in our history, the broader segment of the population seems willing to ponder these structural questions in a way that they hadn’t been before.

JJM Baldwin advocated for a more civilized police force, and thought a “civilian review board” would help empower members of the community to hold the police accountable, which is one of the practical solutions being discussed today, some fifty years later…

NB Yes, that idea of the civilian review board was brought up in a later debate they had on the TV show Open End, when they talked about, among other things, policing, and it does beg the question “How far have we come?” Buckley actually announced his candidacy for mayor of New York soon after this encounter with Baldwin, and one of his central issues during his campaign was his opposition to having a civilian review board. He opposed it because he felt New York wasn’t over-policed, he felt it was under-policed and wanted to increase the police force dramatically and empower them to pursue criminals more robustly. Around this same time he infamously defended Alabama law enforcement officers and talked about our under-policed society.

From Buckley’s perspective, he calls the idea of a civilian review board a political ploy meant to inhibit the police from doing their jobs. By contrast, Baldwin would say that a civilian review board may not be the answer, but it’s one answer to a series of questions we need to confront. Baldwin was there to ask Buckley and others who think like him to try and imagine what it is like to be a Black or Puerto Rican teenager in Harlem with so few opportunities in life, and how they are likely to perceive the police within that context. Baldwin felt that a civilian review board would be important symbolically – that there would at least be a potential for accountability for the officers governing these neighborhoods. To Baldwin, that looked like what Buckley would call a “civilized police force.” That is another example of the stark contrast between Baldwin and Buckley that I discuss in the book, and about how they think about issues that are still very much with us today.

JJM Donald Trump’s philosophy on race – and the contemporary challenges that come from it – seems clearly patterned after much of Buckley’s rhetoric, yet in what must have been an incredible act of restraint, Trump is not mentioned once in your book. Was that by design?

NB I originally named Trump in the prologue and epilogue but ended up cutting his name itself, and one reason for that is that Baldwin was always leery about our fixations on particular individuals in politics, either as heroes or demons, and that they are always manifestations of something deeper, and are in fact always manifestations of us – we are the soil in which they grow.

At times in the book, without mentioning Trump’s name, I refer to white nationalist authoritarianism that is one of the central themes of the book. One of the things that is so powerful about this story in terms of relevance for where we are today is that I went into the research for this book buying into the narrative about Buckley on race as being a story about redemption, that he had views that he came to regret later, but I think ultimately the book complicates that narrative quite a bit. The other thing that is worth noting is that with the rise of Trump we are reminded by some people sympathetic to Buckley that he didn’t like Trump as an individual, and we have some contextual support of that view from later in Buckley’s life.

I argue in the book that I don’t think Buckley can be exonerated quite so cleanly from Trumpian politics, but what I try to do in the chapter leading up to the debate, and again in the chapter that covers the period after the debate, is to show the ways that Buckley was evolving on race, and the ways in which he recognized that there was a racial politics in the kind of rhetoric he had been using in pieces like “Why the South Must Prevail,” and why he resisted the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. History was clearly not going to go the way he wanted it to go in terms of resistance to these broad legislative and judicial steps in favor of Black Liberation, so he was trying to adapt during this period.

It is really important in this one case to think about the ways in which his adaptation is reflective of the broader changes on the American right in our political culture because we could take some of the language Buckley used in the mid-to-late 60’s and it is almost identical to the language we are hearing the right use today. It is a more subtle politics of racial resentment as opposed to an explicit politics of racial hierarchy or antagonism to civil rights, it is a politics that tries to take the energy of white backlash – a term that Buckley embraces in the mid-60’s – and use that political energy to support an agenda of conservative politics. That is absolutely crucial, and we see Trump doing it today, and he has done it from the moment he announced his candidacy in 2015, which has been crucial to his rise. He always acts shocked that people consider what he’s doing to be racist, just as Buckley would be totally shocked that he would be considered racist, or in defense of white supremacy. So, while they have stylistic differences, Trump and Buckley both tap into this politics of racial resentment in order to advance their agenda, and it is absolutely crucial that we understand how and why that works in order to figure out how to combat it.

JJM While running for mayor of New York in 1965, Buckley felt that the way to grow the conservative coalition was to find what was causing people to “seethe with frustration and exploit the hell out of it.” Trump found an issue to run on in immigration – which is of course an issue about race and fear – and he is now using race and fear as the culprit for a campaign of law and order. It is hard not to see his recent deployment of the Feds in Portland – where we both live – as a purely authoritarian act, and I am feeling an urge to participate in protests that, until now, I have steered clear of…

NB Yes, it is definitely a combustible mixture, and his authoritarianism has been there from the beginning, manifesting itself in his immigration policies especially. While it has been bluster in many instances, now we are seeing him send troops in to escalate the situation, and to make things worse for clearly political purposes. This is absolutely terrifying because if we have learned one thing about Trump it is that just about anything he does is not going to be done particularly well. In this case, he sends people in to Portland who are not trained to deal with what they are sent in to do. There is a large group of people within these protests who are animated by different causes and who have different goals in mind. So the question becomes; What are the objectives of the protest movement? What are they hoping to achieve? And then, you have to ask how the law enforcement’s response will impact the goals and tactics of the protesters. People who were not involved in the protest movement at the beginning are now involved and feeling more connected with the protests and want to connect and engage. All of these contribute to this situation escalating.

JJM How would Baldwin respond to this?

NB It is hard to say exactly, but one of the things we understand about him – which is a radically democratic aspect of his politics – is that he was someone who recognized that change was going to come from the people themselves, and how we react collectively to the situation in which we find ourselves is what matters the most. That doesn’t necessarily give us our marching orders because one thing that Baldwin grappled with is what many people are conflicted by now, and that is the question of whether or not we belong on the front lines. He felt this pull in both directions. Does he belong out there on the street, or is his role primarily as a writer, as a witness whose job it is to try and capture what was happening and give people a sense of what ought to happen next? He would feel a sense of guilt at times when he wasn’t out in the streets with the people of the movement. So what you are feeling is a perfectly natural and important struggle taking place for each of us to try and figure out our proper role in this quest for justice, and that’s going to evolve every day.

.

.

___

.

.

An hour-long (and not entirely complete) film of the debate.

.

.

___

.

.

The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America

by Nicholas Buccola

.

.

Nicholas Buccola is the author of The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass and the editor of The Essential Douglass and Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Salon, and many other publications. He is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, and lives in Portland.

.

.

.

This interview took place on July 23, 2020, and was conducted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

Photos of James Baldwin courtesy of Allan Warren. Portrait of William F. Buckley courtesy of Thomas Pelham Curtis

.

.

.