.

.

“[Jazz] is still, for me, the greatest music ever – it just ate its way into my soul, and it became a part of every fabric of my body.”

-Michael Cuscuna

.

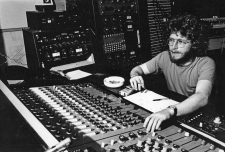

Studio Davout in Paris, 1985 during the making of ‘Round Midnight.

Wayne Shorter, Dexter Gordon, Michael Cuscuna, Billy Higgins, Herbie Hancock, Palle Mikkelborg (or Mads Vinding) and Ron Carter.

(photo courtesy Michael Cuscuna)

.

___

.

…..Few music industry executives have had as meaningful an impact on jazz music as producer, discographer, and entrepreneur Michael Cuscuna. His life has been dedicated to music — first as a young fan, frequenting the record shops and clubs of New York, then as an ambitious and visionary radio host, and again as a producer who, while with Atlantic Records, worked with prominent artists across several musical genres.

Michael Cuscuna at the Bearsville Studio in Woodstock, working on Bonnie Raitt’s 1972 LP, Give It Up

…..This varied early life experience led him to imagine the possibilities of diving deep into the catalogs of the great jazz record labels (Blue Note, now in its 80th year, being the most prominent) to reveal unreleased gems, and ultimately marketing the tracks in packages with an artistic sensibility appropriate to the music’s rich aesthetic. Cuscuna built this model, and has followed it since the 1980’s on Mosaic Records (the label he co-founded in 1982), creating limited box sets from licensed music and offering them to consumers via mail order only. This has proven to be a brilliant and resilient strategy, and the resulting success is no small feat, particularly in light of the challenges facing music executives competing during a generation of dwindling demand for packaged media.

…..What Cuscuna has done, then, is .mine, find, and market .essential jazz music. In the process, he built rewarding relationships with artists and fellow record executives, and has contributed mightily to the possibility of making historic recordings and musicians relevant to a younger generation gaining enthusiasm and energy for discovery.

…..A career of this consequence merits recognition. Since his is a voice filled with spirit, wisdom, and vision about a music that was central to the American experience during the 20th Century, we asked Michael to participate in a conversation about his life and career.

…..The following interview — which we are grateful for — took place by telephone on April 22, 2019, and was hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita.

.

.

___

.

.

.

“I remember once I was doing a record with Dexter Gordon at 30th Street called .Gotham City, and Art Blakey was on drums. During the session Art looked at me and said, ‘Man, you remind me of [Blue Note Records co-founder] Alfred Lion.’ That was the greatest line I ever heard, you know?”

-Michael Cuscuna

.

.

_____

.

.

JJM. Where did you grow up, Michael?

MC I grew up where I am now, Stamford, Connecticut, which is a suburb of New York. From a jazz point of view, it was a great place to grow up because during the 1950’s and 1960’s, a lot of jazz musicians lived around here. Also, at that time there was a record shop in Stamford called Economy Music that I worked for while I was in high school, and during that experience I got to know more about jazz and all the other musical genres, learned the retail record business and, in general, the record industry.

Stamford was, and still is, the first stop on all of the express trains from New York to New Haven. When I was growing up, the last trains ran until about 3:30 in the morning – that last train was called the “Milk Train.” For those of us who were teenagers and addicted to jazz, and who also had understanding parents, we would take the train to New York and go to the clubs, which we were able to get into even at age 14 or 15 because the drinking age at the time was 18, versus 21 everywhere else.

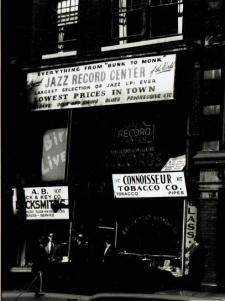

photo courtesy of Fred Cohen/Jazz Record Center

The original Jazz Record Center, in an undated photo

.

My cousin and I and a couple of our friends went to New York frequently, getting in around 4:00 or 5:00. We would go down Sixth Avenue in the 40’s blocks to all the different record shops – stores like Discount Records and the Jazz Record Center on 47th Street, where you could ask the employees to hear a record and they would play it for you. There were all kinds of jazz mavens in the store – I remember a guy named Jay was running it at the time – and you could talk to them and learn stuff from them.

After we left the stores, we would grab a bite somewhere and then go to the clubs, where I heard people like John Coltrane’s quartet, Miles Davis with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams, and dozens upon dozens of others over a few years. And in those days, of course, it was very inexpensive – you paid $2.50 to get into a club, .75 cents for a coffee or $1.25 for a drink that you would just nurse, all the while hearing the greatest music ever, which is still, for me, the greatest music ever – it just ate its way into my soul, and it became a part of every fabric of my body.

JJM When you were eight years old or so, what did you want to be when you grew up?

MC Well, when I was eight years old, I didn’t know – I probably just wanted to make it to the sixth grade! I loved music. I started collecting 45’s when I was about seven years old, and I was a complete R&B junkie at the time. When I was about ten, I told my father I wanted to have a drum set, so he got me this beginner’s drum set and I started playing along with records in the basement. I eventually convinced him to get me a drum teacher, whose name was Lenny Fields, and he taught me the basics of drumming. Up to that point I was just sitting in my basement, playing the melodies on the drums – I didn’t really know what I was doing. As I got to age 12 or 13, I started to be exposed to Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, and even earlier guys like Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, and learned what the power and the touch of the drums were. It opened up a whole new world for me. But I eventually realized I wasn’t a great drummer, nor was I going to be a great drummer, and I switched to alto saxophone and flute, and eventually tenor sax and flute, and even then I wasn’t a good musician. I couldn’t sight read quickly and I was a lousy improviser, so I realized by the time I graduated high school that being a musician was not for me.

When I went to college in 1966, I attended the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, which is in the upper echelon of business schools in America, and I thought that I may one day want to run my own record company. But it dawned on me during my first year there that they were teaching people to be CEO’s of major corporations, not small business owners, so I bailed out of Wharton and, much to my father’s chagrin, became an English major. In the meantime, I did a nightly jazz show on WXPN, the college radio station, which gave me the radio bug, and I started to think of new ideas for shows. This was 1966, as the avant-garde was blossoming – thanks in large part to Coltrane’s patronage – and I started doing a weekly avant-garde show featuring Marion Brown and Albert Ayler and Archie Shepp and all of these new names that were coming up. Eventually, on the weekends, I did an afternoon show that was a complete mixed bag – I would play jazz, but I would also play singer-songwriters, and I would also play hip rock groups like the Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe and the Fish, and I am sure the Rolling Stones, so it was kind of a free form thing. And that idea spread around the country, which became underground FM rock…

JJM .KSAN in San Francisco is what I grew up on…

MC. Right. Tom Donohue was one of the first, and this was happening simultaneously around the country, and it was something whose time had come. In the meantime I was writing for Downbeat, as well as producing jazz concerts in New York and Philadelphia, just on a shoestring. I also wanted to produce records, and I always daydreamed about records I’d like to hear – one example is Denny Zeitlin was getting a lot of attention at the time, and I thought it would be great to hear him and Herbie Hancock on a record together. So, I’d be imagining different things.

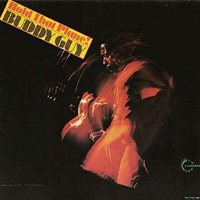

At the time I was living on Lombard Street in Philadelphia, down the street from Dick Waterman, who managed a lot of the blues acts at the time. He became a friend of mine, and through this friendship I got to know many of the blues musicians, especially Buddy Guy, who I became very close to. He used to come on my weekend afternoon show and play the acoustic guitar and sing, and in the late 1960’s I wrote a feature article about him in Downbeat, so he knew me and knew that I wanted to produce records. He called one day to tell me that he was going to do his last record at Vanguard, and since he didn’t like working with the people there, asked if I would like to produce the record with him, just so I could get my feet wet. I agreed to do so, and met him in New York and produced the record, which was an odd mix of stuff eventually called Hold That Plane. I hired Gary Bartz to play on it, and the bassist Bill Folwell, and Barry Altschul was on drums, and Buddy brought some of his guys in. It turned out alright.

After that, I told Buddy I would like to call a friend of mine at a new label in Los Angeles, Blue Thumb Records, and I talked to them about doing an acoustic album with Buddy Guy because I did it on my radio show for a year, and it is really effective. My idea was to reunite Buddy with Junior Wells, and since Junior Mance was a friend of mine we could do a trio and call it “Buddy and the Juniors.” Blue Thumb agreed, and sent me a budget. So, that was the second record I produced. Little by little, one thing led to another, and I found a singer-songwriter named Chris Smither, who was playing a lot on the mainline in Philadelphia. I loved him, and got him a deal with Poppy Records, and we produced three records for them. Then, Bonnie Raitt – who was Dick Waterman’s girlfriend at the time, and I didn’t even know she played guitar or sang – played at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in 1969 or 1970, and I was knocked out by her. She told me she liked Chris Smither’s records, and asked if I would like to produce her record. I told her I would, and ended up doing her Give it Up record.

Meanwhile, I was still doing underground radio and got hired to come back to New York and do the morning talk show on WABC-FM, which was totally free-form radio. When I got tired of getting up at five o’clock every morning I asked them to switch me to the afternoon slot, which I did for a while. While that was fun, I knew that talking into a microphone and playing records for four hours wasn’t the be-all-and-end-all for me, especially since radio was being formatted and the reigns on programming were tightening. So, I just left.

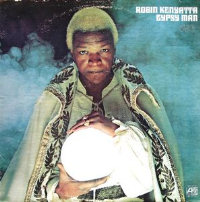

Robin Kenyatta, Gypsy Man, 1972

.

Dave Brubeck, Two Generations of Brubeck, 1973

.

Art Ensemble of Chicago, Fanfare For the Warriors, 1973

As luck would have it, the secretary for my friend from Philadelphia Joel Dorn – who was working at Atlantic Records – listened to my radio show, and told Joel that I had just done my last show on WPLJ. He called me and said he is looking for someone to help him out at Atlantic as a staff producer, and asked if I would be interested in that job. I said, “Shit, yeah!” So, I started doing that and worked for Joel, Nesuhi Ertegun and Jerry Wexler. They assigned me people like Dave Brubeck and Robin Kenyatta, and I was able to sign other people, like the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and the singer songwriter Garland Jeffreys. So, I was getting a great amount of experience there. From there it got a little frustrating once Atlantic Records moved from Columbus Circle down to Rockefeller Center because it got more and more corporate. I became unhappy, as did Joel. We both left at different times, but I left to go freelance, which has essentially been my mindset ever since. I have been freelance producing for a lot of labels, mostly jazz, but I love all kinds of music.

JJM . So much of your success, it seems, has been in effectively marketing your ideas. Mosaic is an example of that. Do you have a marketing background?

MC. I have no marketing background, I mostly operate on gut instinct. All I wanted to do was make the record I wanted to make and once it was done, walk away from it. I wrote or supervised the liner notes, and I had a say about the album artwork, but once an album was released I only had a minor interest in the aftermath of it – how well it sold, what the marketing plan was, or how it was being distributed. It is a kind of Zen-like thing that once it’s done, its done – it is no longer in my control or grasp and whatever happens with it, happens.

JJM . The business model for Mosaic is an interesting one, and you have survived when so many others have not. How did you arrive at this model?

MC . I created that model out of necessity and knowledge. Because I had worked in retail, and I also worked in radio and records, I knew all the pitfalls of the record industry. When I was working at Atlantic as a staff producer, I had to pay attention to what else was going on. I will never forget one day, at the end of the fiscal year, the head of sales at the time showed us the albums we had in excess of 30,000 copies that we couldn’t sell, and he informed us he was going to sell them to cut-out [surplus inventory] places like Scorpio. While I understood why, I disliked the practice because it cheats the artist and it cheapens the product, but it is because of the tax structure of this country that if you are carrying over inventory, you are paying tax on it, so you have to somehow get rid of that inventory or you’ll get killed on taxes. So, of course the smart thing to do is to pay attention to your manufacturing and only manufacture what you need on a monthly or a quarterly basis. So, this is just an example of some of the tricks I knew, as well as the pitfalls.

When Charlie Laurie and I started Mosaic, the proposal we made to Capitol Records in 1981 was to revive Blue Note. On page eight of the proposal, in the catalog exploitation section, I mentioned box sets, and the reason was because Charlie and I both grew up with all those great 1960’s Columbia box sets – which were conceptual, they weren’t complete “this or that” – covering history like 52nd Street, and artists like Billie Holiday, Fletcher Henderson, Jack Teagarden and so many other conceptual boxes. I was impressed by the booklets and the whole gestalt.

When we made this proposal to Capitol, I was living in Los Angeles with a girlfriend, and I was out of work – everything dried up and I was just living off my savings. But, during this time I would go to the Blue Note vaults and I would listen to every tape and make notations, figuring that someday this would all be of use to me. God, was it! It was amazing. So, thankfully I used my lost time very well. But once I got through the entire tape vault, I was suddenly done, and I then looked at all the 16-inch lacquers sitting there, and thought that maybe I will organize those as well. These were the Blue Note sessions from 1940 to 1951, which I started to clean up and listen to, and found about 30 minutes of unissued Thelonious Monk – two tunes and vitally fascinating alternate takes that were more than worthy of being released. But, unless you are Creed Taylor, who would occasionally get away with it, you can’t put out a 30 minute LP, so I began thinking about how to release this.

It dawned on me that the Monk Blue Note sessions were all from the 1940’s and early 1950’s, in the 78 R.P.M. era, which meant when they got released on 12 inch LP it wasn’t complete – different sessions were all scrambled together, which personally drives me nuts. So I thought that I would take all of Monk’s work for Blue Note, pull it apart, rescue any worthwhile alternate takes, put it all in chronological order, retransfer the whole thing in today’s sound and then release it as a complete set. That was the only way to rescue those 30 minutes. That is what gave me the box set idea.

Then, one night while we were still waiting for an answer from Capitol I started playing with the numbers and I called Charlie up at midnight and I told him I think we gave away a great idea, that this box set thing could work if we did it as our own business, but in order to do so we would have to take a page out of the art world and make them hand-numbered and limited edition sets, otherwise the rate of sale would be so slow it would kill us. As we started working on that idea, it made sense. So, when Capitol turned down our idea to resurrect Blue Note, we were thrilled because we could start Mosaic, which we did immediately. We started with a bunch of projects from the Blue Note vaults and the Pacific Jazz vaults that they had no interest in dealing with. That is how Mosaic began, and of course it didn’t go quite the way we planned, it went much slower – we worked for two or three years without taking a salary, but it finally got its footing and then just kept going.

JJM . Having worked with the Blue Note catalog for so long you must feel a connection with Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff. Do you have anything in common with the way you run Mosaic and what they did at Blue Note?

MC. Well, any independent record company, whether it was Blue Note, Savoy or Prestige in the 1940’s and 1950’s, or when we started Mosaic in the 1980’s, learns that you have to sink every dollar back into the business to make it grow. You can’t live off of it for a while, and you have to keep investing in yourself. So, we had that in common, but the interesting thing that I realized when I finally got to meet Alfred in the mid-1980’s was that we had a very similar way of working. No matter what kind of music it was, I had always felt very strongly about rehearsing and planning sessions, and making sure everybody is fresh and ready to record. I learned that that was Alfred’s system of working too. It is not any great revelation, it is common sense, but a lot of people don’t do it that way. So, we had the same attitude about getting the finished product to where it sounds like it should sound. I remember once I was doing a record with Dexter Gordon at 30th Street called Gotham City, and Art Blakey was on drums. During the session Art looked at me and said, “Man, you remind me of Alfred Lion.” That was the greatest line I ever heard, you know?

JJM . Were Lion and Wolff good businessmen?

Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff, 1965

MC .Yes, they were good businessmen in terms of keeping a company together and growing it – their success is what killed them. Their distribution system included about a dozen distributors around the country, and records by artists like Hank Mobley and Sonny Clark would sell about 3,000 copies nationally. All went smoothly – the records get out and everyone gets paid. But when Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder hit and literally blew through the roof – they had 4,000 copies on the floor but had 16,000 outstanding orders – holy shit, suddenly they were in a new league! What Alfred Lion told me about this, which I totally understand, is that they had this hit which customers wanted him to reproduce, but the distributors had not paid Blue Note for previous invoices, which created a cash flow problem for the label. Horace Silver’s Song for my Father finally got them out of that mess. But they were undercapitalized to sustain any success, and realized they had to sell, which they eventually did, to Liberty Records.

JJM . In 2001, the jazz writer Richard Cook wrote a history of Blue Note Records, and in it said that in the 1950’s, “most of the [Blue Note] record buyers came from black neighborhoods.” Who buys Blue Note – or Mosaic – records today?

MC . Today’s jazz consumer covers the entire spectrum, from age 20 to 80, and I think African American consumers have come back to jazz in the last 20 years. When I went to the clubs in the early 1960’s – mainly at Birdland, Five Spot and the Village Vanguard, I noticed that the jazz artists that attracted a large black audience were John Coltrane, Max Roach, and a few others, but more often than not, if the Jazz Messengers or Monk played Birdland the audience was 70 percent white. In the early 1960’s, acts like James Brown, Otis Redding and Ray Charles exploded and were siphoning off some of the black community’s interest in jazz, but there were still jazz clubs in all the urban areas of the major cities. They started to die in the late 1960’s when there was some rioting and unrest, and this was also when the avant-garde turned a lot of urban black people off from jazz – they didn’t want to hear about Albert Ayler or Archie Shepp or Pharoah Sanders, they just wanted to hear a great organ and tenor band. These things chased them away at the same time the underground rock thing was getting really interesting, so the jazz scene was in trouble, and clubs started going out of business. There were hangers-on – in Philly there was The Aqua Lounge, Washington D.C. had the Bohemian Caverns, and there were a couple clubs up in Harlem – but for the most part the urban backbone of jazz as an industry was shriveling, and that included not only clubs in the black neighborhoods, but also 24 hour commercial jazz radio that was the real glue to the economics of the jazz community in each city. As those stations went away, so did a lot of businesses.

JJM . To your point, we have a 24 hour jazz station in Portland which is a major reason why jazz is successful here in Portland. As far as live shows I attend, when legends like Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, Lou Donaldson and McCoy Tyner play it tends to bring out a sizable, but older jazz crowd. But, when an artist like Kamasi Washington plays, the crowd is young and large, and it makes me feel more hopeful for the future of the music than I did maybe 15 years ago.

MC .Oh, I think there absolutely is reason to feel that way, and not only in terms of the audience, but also in terms of the musicians. There are so many great musicians out there now, it is unbelievable!

JJM. What are some of the notable recordings you have heard in the last couple years?

MC. I often read reviews but I don’t always get to hear a lot of music other than what I am working on, but there are so many incredible musicians from the generation that is now 40 and up like Vijay Iyer, Brad Mehldau, Joshua Redman, Jason Moran, and Greg Osby. I also hear younger people like Ambrose Akinmusire – the first time I saw his band it was made up of Walter Smith, Jr., Gerald Clayton and Justin Brown – what a killer band, it reminded me of the first time I saw Miles, Herbie, Ron, Wayne and Tony. My god, these people are so empathetic and playing at such a high level of trust with each other!

There is so much music out there that is really extraordinary, the difference now is that they are not getting record deals – they are building their careers through the Internet, they are putting out their own records, and they are playing live. It is amazing how much music is being played live in major cities all over the world, and being played by young guys whose names I don’t even know – they are 23 and are brilliant! You don’t read a lot about them, but they are making a career and are making an impact on an audience, and they are working all the time.

JJM . You and I grew up in the LP era, when the artistic canvas was about 45 minutes long, and the listener had to get up off the couch to turn the record over, which meant entire sides of albums were being heard. The generation after us grew up when the CD was the primary format, and the creative space went up to 70-ish minutes. What went through your mind when you saw the compact disc for the first time, and understood its storage capacity and ability for consumers to skip through tracks? Did you understand the artistic challenges this canvas would pose?

MC .The first thing that went through my mind was, well, all this stuff that I wanted to put out on albums, now I have room for bonus tracks! My second thought was that 50 minutes is a lot of time – I always remind musicians that just because there are 77 minutes of music available on a CD, you don’t have to fill it all up. I also tried to get them to understand the importance of recording some tunes that people recognize so listeners can get a sense of their personality against a piece of music that is familiar ground to both the artist and listener – don’t make it uncharted waters for 65 minutes because no one is going to make it through those 65 minutes. To this day, 40 years later, I don’t know how many people make it through an entire CD. I know that I get CD’s of people that I love, and I will listen to 10 minutes here, 20 minutes there, but I have never sat down to listen to an entire CD unless it was my production and I had to approve it as a test pressing. Other than that, it is too much.

JJM .Technology has done a number on our brains, and people today don’t have the attention span of those who lived 50 years ago. It is ironic that a larger canvas exists for artists to create on today, but listeners don’t have the attention span – or time – to fully appreciate their work. So, the artist is left with the challenge of providing value while keeping their audience’s attention.

MC .Yes, you have to be really good, and not take your audience for granted.

JJM .A question you must get asked a lot is, what is your all-time favorite Blue Note album?

MC . I tell people who ask me that question that I will have an answer for you now, but if you call me back in a half-hour it will be different. I suppose Coltrane’s Blue Train would be my favorite. The first Blue Note record I ever bought was Art Blakey’s The Big Beat. At the time I was a kid and still playing drums. That album had an enormous effect on me, but there were two albums that had the deepest effect on me in my life going forward. One Friday I went into Economy Music and there were two new Blue Note releases, Kenny Dorham’s Una Mas and Jackie McLean’s One Step Beyond. I had the money so I bought both of them. I knew who Kenny Dorham and Jackie McLean were, but I didn’t really have a sense about what they sounded like. I played these two albums incessantly for the entire weekend, and in that time I not only got introduced to Kenny Dorham and Jackie McLean, but I was also introduced to Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Bobby Hutcherson, Grachan Moncur, and Joe Henderson. That is a lot of “first times” for one weekend! And I was immersed in it, because both albums had really long tracks – in fact, the tune “Una Mas” was the only song on one side of the album. I was drawn into it. I was hypnotized by it. That was my most bonding experience with Blue Note.

JJM . When I was a kid going to record shops in the San Francisco Bay area, the Blue Note albums were like eye candy, and the art would draw me to them. Once I had them in my hands, I was hooked and had to know more about the artists, where they came from, what other recordings they were on…

MC .The nice thing about that is you carve your own path of self-discovery through all of that stuff, which is great. Today, there is so much going on that I don’t know how anyone finds their way through it.

JJM . Well, Blue Note was genius about connecting the album cover art to this path of self-discovery, which brings me back to an earlier question about your marketing background, because Mosaic’s packaging is brilliant, and filled with great information. But, I wonder, is it only seasoned record buyers who this strategy appeals to?

Reid Miles

MC . Reid Miles never heard a note of a Blue Note record. Alfred, who was very expressive, told him the concept behind each record and Reid nailed it. He only listened to classical music but he grasped Alfred’s idea behind each record. Each Blue Note record was completely different, but they all looked like Blue Note. Ingenious. As for today, you would be surprised by how many people in their 20’s and 30’s want all that information. That’s why I don’t think packaged media is going to go away anytime soon. It is going to diminish and diminish, but people want photography, people want information.

JJM . You commission great writers to contribute liner notes for your box sets…

MC. I pick writers that I think write great, who write from the heart with some knowledge, and can tell a story. To me, the most supreme writer of all is Dan Morgenstern, and behind him was Ira Gitler and Nat Hentoff, who are no longer with us, but they had a knowledge and feel for the music. They were friends with the people who made the music, and I always thought that was very important. You know, if you want to be a critic instead of a journalist, and you sit behind a typewriter in your own little apartment and are making judgment calls and decisions without regard to the people who made the music and without a lot of knowledge of those people, I have no use for that at all.

JJM .If you had an opportunity to have dinner with three Blue Note artists, living or dead, who would they be and what would you want to learn from them?

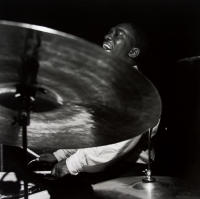

Art Blakey, 1962

MC .Art Blakey would definitely be one of them, and Bobby Hutcherson, and the third being either Joe Henderson or Herbie Hancock. Art Blakey, aside from being the greatest, most swinging drummer in the world, also created an amazing group, and even though he never wrote a tune, the songs on his albums all sound like Art Blakey tunes. He was an extraordinary musician, but he was also one of the most unique human beings I ever knew. He was a joy, he was a wise man – he was also a pathological liar, and I think he would be the first to tell you that – and he was so strong and swung like mad! He was so smart in terms of how to get through life and how to shape your life and your music. He was a sage, a prophet in many ways. I don’t think a day goes by when I don’t think about him within the first couple of hours. I miss him terribly – he was such a big loss to me.

Bobby Hutcherson, 1963

.

photo by Francis Wolff

Herbie Hancock, 1963

Bobby Hutcherson was one of my favorite musicians, and also one of my best friends. He was my son’s godfather. We just had wonderful times together over the last 40 or 50 years. Bobby was like a zen-master, he had so much life wisdom and ways to get through life in an enriching and calming way. He was always the first person I would call if I was in some kind of emotional turmoil.

Herbie Hancock is a very generous and empathetic spirit, and even though he is so busy, he is completely down to earth and completely there for you. You can learn from him just by the things that fall out of his mouth by accident – he is just so bright. He played classical piano on stages in Chicago at age nine, and then studied engineering in college – he was the kid who would have a shirt pocket full of pencils! He was the ultimate geek. Then he became hip and had a lot of things to do, but he is still, in essence, a real grounded, geek-oriented guy.

Joe Henderson, 1963

So the third Blue Note artist to have dinner would be Herbie, or it would be Joe Henderson, who was an enigma wrapped inside a riddle – he was the most mysterious guy I ever knew, a very private guy. We used to call him “The Phantom” because he had a tendency to disappear when he wanted to – and I mean literally disappear. I remember one Woody Shaw record we were doing at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio in New York, and Joe just dematerialized. At 30th Street, there is the studio, the control room, and there are bathrooms in the corridor below. We went looking all over for him and he was in none of those places. I went outside to have a cigarette and he wasn’t there either. So I went back in and I told Woody that I didn’t know where Joe is, but we have to get moving, so let’s run down the next tune without him. Suddenly, there he is! He just materialized in front of his microphone, and everyone looks at him like he is “The Phantom.” Joe was one of 13 children and a real private guy who liked to be alone, but if you were his friend he would welcome you in. When we would do gigs in Japan he always asked for a Japanese room, which is a very austere space with the mats, the thin futon mattress and no furniture. He was a stoic guy and very strange, but one of the most fascinating characters in the music.

JJM .Are there any Blue Note artists, that when you listen to their recordings now you wish you were around to have possibly steered them in a different direction?

MC. That’s an interesting question. Alfred, I think, was a producer who liked to shape stuff, but he never forced anything on anybody, so everybody had the rope to hang themselves and be themselves. Alfred was always there to influence it for the better.

JJM .Right…But take a Blue Note artist like Stanley Turrentine, for example. He played very lush, heavily orchestrated, often corny tunes. Can you imagine him having been utilized in a different way?

MC. Most of his Blue Note records were with small groups, some were organ, some were piano, bass, drums with heavy piano players, like McCoy Tyner and Horace Parlan. But, toward the end of the 1960s, he made two really bad albums with good orchestrators, like Thad Jones, but the concept of the album sucked, and it included horrible tunes like “Little Green Apples.” It was understandable that some musicians would record something that they felt was going to sell more so they could go on the road and make more money and work more regularly – it doesn’t mean that we as aficionados have to buy them or listen to them. There were two Turrentine records that I never bothered to re-release in the CD era – I didn’t think anyone gave a shit, and it wasn’t going to serve any purpose for Stanley at that point. He was still alive but he was playing something different at the time. So, many people have made albums that they regret, but the merciful thing is that most failures are forgotten, and successes are remembered.

JJM .What do you want to be remembered for, and what do you want to yet accomplish in your life?

MC . I don’t know what I want to accomplish. I never really had an agenda, I just took life as it came, and as mysteries or problems presented themselves, I would work hard to find a solution. The reason I got so obsessed with the Blue Note vault was because when I first started producing records, musicians in the studio would start talking about records. I would hear things said like, “Remember that Lee Morgan record we were on? It never got released.” I would overhear this stuff and I started to bring a notebook and I started making notes of all these conversations, then I’d start asking musicians. I remember I was doing an Andrew Hill record and he came over to my house one night to plan the record, and at the end we were just hanging around, having a glass of wine, and I asked him how many unissued Blue Note sessions is he on? This was in 1974 so nothing was out. He thought about it and said, “Eleven.” I asked him if he remembered who was on those recordings, and he said he did, and listed the complete personnel on all of these eleven sessions. Later, as I found the tapes and found more documentation, he only got one bass player wrong, the rest of it was perfectly right. He had an amazing memory for that kind of stuff.

So that led me on to another path of finding out all this great unissued material by Grant Green and Lee Morgan and Hank Mobley and all these other guys, and that started through a whole thing that gave me a life with the new Blue Note. It also inspired me to create Mosaic Records. So, I just did things as they came. I don’t think at 70 years old that I have anything I am really dying to prove or dying to get done, but as things present themselves, I’ll rally to the challenge.

JJM . Do you ever think about retirement?

MC .No, and do what? I am blind as a bat, I can’t do any sports, and I am too old to do drugs. What the hell am I going to do? I feel so lucky that during my entire life I have never done anything that I didn’t want to do. I have only done the stuff that I love, and that is an amazing thing to say 70 years into your life.

.

.

_____

.

.

Click here to visit the Mosaic Records website

.

.

This telephone interview took place on April 22, 2019, and was hosted and produced by. Jerry Jazz Musician. editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

all photos courtesy of Michael Cuscuna

.

.

This is wonderful, Joe, an interview that reads like a genuine conversation. And I learned a thing or three.

Great job Mr Joe, it moved right along

Anything that MICHAEL Cuscuna has to say or write is something I automatically know will be worth my time and attention. Thank you, Michael.

That was supposed http://www.sigsart.com

Very enjoyable interview …..and without Michael a lot of jazz would be unheard today. I have 8 Mosaic Box sets plus 5 of those mini-3CD boxes that Mosaic once put out and now waiting patiently for the 9th which is on Woody Herman’s first heard and material he did in the 1950’s.

Like Michael , I enjoyed the Blue Note recordings but also juxtaposed those with the more laid back (West Coast if you will)recordings on Contemporary which somehow gets short shifted . Maybe Michael should look into that catalog for some unearthed gems.

Please note I made an error on my e-mail -it’s [email protected] not [email protected]. Those finger checks get me every time.

Inspiring! I had a chance to chat with MC a couple times when chasing down out of print Mosaic sets. The music world is better off because of him and I loved hearing more in this interview.

anyone loving jazz should say a thousand thankyous for mr. cuscuna and his monumental work the last fifty years keeping the great music and musicians alive for us and the next generations. the “secretariat” of record producers and one of my great heros of the modern era.

I am Mr. Cuscuna’s age, and grew up in Phila. I remember him on WXPN. I picked up on Mosaic early on; I have close to a hundred sets, lp and cd, and have been disappointed with exactly one. I won’t say which one, but I think I’ll get it out and listen again. Also have most of the 3-cd Select sets. My only regret is all the sets,especially early on when I just couldn’t afford it, that I didn’t get. I really would buy every set that you put out. Michael, thank you very much, and keep on doing it. I will keep on buying,and enjoying.

Good interview with MC about one part of his career. But beside Biue Note and Mosaic he was also responsible for recording many Antony Braxton discs and other forward looking players for Arista in its brief flirtation with Jazz. An interview on his experience with Braxton et. al would be as — if not more — interesting ads this one.

Wow – a fantastic interview, especially interesting for a European (= geographically far from the source, though in Brooklyn for the past two decades) musician my age (62) who grew up listening to almost all the musicians Michael Cuscuna talks about! Aside from reading about some musicians’ personalities I really appreciated take on the length of LP’s vs CD’s, and his statement: “The nice thing about that is you carve your own path of self-discovery through all of that stuff…” which I find true for both, my time as a ‘jazz-infected’ kid and then becoming a musician – in fact, it still is true (with a lot less listening-time though). Thank you for this insightful interview!

Hey Joe – great job.

I missed it the first time.

RIP Michael.

Thank you,

Bob Riddle

21 apr 2024