.

.

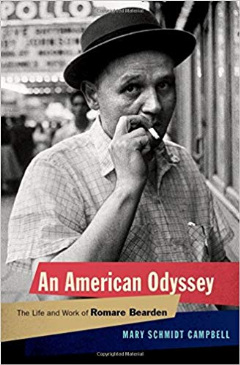

Mary Schmidt Campbell, author of An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden

.

_____

.

Growing up in the era of the “New Negro” and the Harlem Renaissance, Romare Bearden began his artistic career immersed in the rich visual heritage of black life. He became a member of a close-knit artistic community in Harlem, producing first cartoons then paintings expounding social justice. Over the course of the Depression, the New Deal, and World War II, he avoided representations of race, though still grappling with what he saw as a “tyranny of the mind” created by distorted portrayals of black life in America.

Disillusioned with the New York avant-garde, he went to Paris. When he returned to an America in the midst of the Cold War, he floundered creatively, nearly abandoning art entirely. The Civil Rights Movement, however, reaffirmed Bearden’s bond with a community of black artists in the form of the collective Spiral. The collages that became his signature works followed soon thereafter, and his influence grew. Until his death in 1988, Bearden championed black artists, convinced that they would emerge as a defining force in American visual culture.#

Mary Schmidt Campbell, who as a young art curator met Bearden in the 1970’s, has written a comprehensive account of his work, .An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden (Oxford University Press).

In a January 17, 2019 telephone interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Dr. Campbell – president of Atlanta’s Spelman College – discusses the remarkable life of this important American artist.

.

.

________

.

.

“My intention is to reveal through pictorial complexities the richness of a life I know.”

-Romare Bearden

.

“Through an act of creative will, [Romare Bearden] has blended strange visual harmonies out of the shrill, indigenous dichotomies of American life.”

Ralph Ellison

.

.

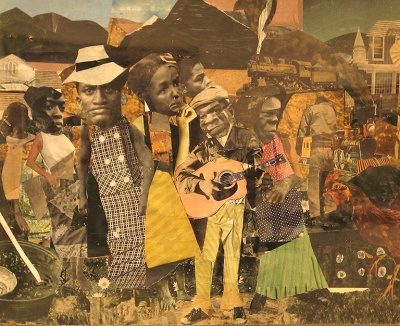

“Watching the Good Trains Go By,” by Romare Bearden, 1964

.

.

________

.

.

JJM Thanks very much for joining us…What is your background?

MSC My undergraduate studies are in English literature, where I also took one year-long course in modern European and modern American painting and sculpture, which I fell in love with, so much that after I graduated I decided to become an art historian. I then studied Art History in graduate school and earned a PhD in the Humanities. Along the way I also discovered museums and the art of curating, and determined that is where I wanted to put my art historical expertise.

My first job in New York was as Director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, a position I held for ten years. During that time the Studio Museum became the first accredited black fine arts museum in the country. Subsequent to that I went to work for Mayor Ed Koch as New York City’s Cultural Affairs Commissioner. When Koch was not reelected, I then served for Mayor David Dinkins. So, combined, I served four years in government. After leaving there I spent 23 years as the Dean of the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University (NYU), one of the country’s leading conservatories, and while there I was immersed in a wide range of disciplines that actually had nothing to do with art history – it was film production, theater, dance, photography, emerging media, musical theater writing, Performance Studies. So, I had two decades of really being immersed in the practice and training for the arts. I also served as vice chair of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities during President Obama’s administration, and am currently president of Spelman College.

JJM .You wrote in the introduction to your book, “Bearden’s odyssey was an often tortuous journey of making art, a decades-long process of first trying on then discarding one approach to painting after another.” Throughout the book you talk about Bearden’s creative life, and his ability to transform his art as he himself evolved. What is your personal experience with Romare Bearden, and what led you to writing this book?

MSC .When I was a graduate student, studying Modern American Painting, my professor challenged me to do a presentation on some aspect of American art that is not in the history. I told her that I was going to do something on black American artists, and she said to me, “Well, if you are, there is one artist that you must see, and that is Romare Bearden.” At the time I had no idea who he was. She handed me the catalog from his retrospective from the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), and the work just blew me away – it was just so vivid, bold, and audacious. Bearden’s show started at MOMA and it traveled around the country, and when it came back to New York, to the Studio Museum in Harlem, my husband and I went. When I walked into the Museum I was absolutely captivated.

Here is what is key; when we came out of the show I told my husband that we should go find more of his work, but after going to every museum we could possibly think of that had either modern art or American art, we could not find even one single piece of work by Romare Bearden. At the end of the day, my husband suggested I try calling him. I found his number in the phone book and called him from a pay phone, and he answered, and after I introduced myself he said he only had twenty minutes, and invited us to come over to his place on Canal Street in Chinatown. He lived on the fifth floor, so we walked up the stairs and when we got there, he stood there and greeted us like we were his best friends. We ended up staying for two hours in his home, while he showed us paintings, sketches, drawings, collages – anything that he had hanging around, and he had stuff all over the place.

A few years after that I was asked by the local museum – I was studying in Syracuse, New York at the time – to curate a show of his work, and, much to my surprise, Mr. Bearden came to see the show. Two years after that, he called me at home and said, “I have just the job for you!” – it was the Director’s position of the Studio Museum in Harlem. So, I felt as though I owed him an enormous debt of gratitude, because of his work and his kindness. I later discovered that he exhibited the same kind of attention to other artists and young scholars. His support made all the difference in my life.

JJM .So you must have really felt his presence while you were writing this book…

MSC .So that is very interesting. When he was alive, I always held him in awe – it was “ROMARE BEARDEN” in all caps – and honestly, it was not until after his death in 1988 that I could peel away that reverence and take a clear-eyed look at his life and his art. I had to shed some of that awe and reverence in order to write an honest book.

JJM .His life is fascinating, not only from an artistic perspective, but also just in terms of living a great American life. He grew up in a strong multi-generational family, and he lived in many different places. Who was most influential among his family members during his childhood?

Bearden’s grandmother Cattie Kennedy Bearden, great grandmother Rosa Kennedy, and great grandfather H.B. Kennedy with Bearden, c. 1911

MSC .His great-grandfather was a pillar, a rock. He was a remarkable man. His great-grandparents were emancipated slaves, and his great grandfather became adept – almost in the way Romare Bearden became adept – at continually reinventing himself. Even before they got to Charlotte, which is where Bearden was born, his great-grandfather had worked in the home of Woodrow Wilson’s family, and while he was there, started a small business selling ice cream. When he came to Charlotte, he was a mail agent on the railroad – when the railroad was being built Charlotte was one of the main textile centers – and he used that money to buy land and houses, as well as to open a grocery store. He also made an effort to have a political appointment at the mint in Charlotte. So he was so incredibly entrepreneurial and always had a lot of drive within him, and I think the notion that you could continually invent and reinvent yourself and find ways of leveraging one thing to get to the next became a part of Bearden’s DNA.

JJM .He spent the bulk of his childhood in Charlotte, correct?

MSC . That is what I probably would have said ten years ago. By the time he was three or four years old his family had moved from Charlotte so he spent some of his summers there, and some of his summers were also spent with his grandmother in Lutherville, Maryland, outside of Baltimore. He also spent a year in Pittsburgh during his elementary school years. He then returned and spent two years at Peabody High School in Pittsburgh. Earlier in his childhood, his family moved to Canada for at least a year. So he moved around a lot, but if I were to look at all the years and months and totaled them, he probably spent more of his time in Harlem than any other place, and it became their home and their focal point, certainly for his mother, and for him as well, even though he went to these other places occasionally.

JJM .Regardless of where he spent the bulk of his time, it is safe to say that he spent his childhood in Harlem during the time that is now known as the “New Negro Movement,” when the caricatures of African Americans were, to put it mildly, disrespectful, but it was also a time when the artistic community there was blossoming…

MSC .Absolutely.

James Van Der Zee

.

___

.

Photographs of James Van Der Zee

.

.

.

JJM .What is always fascinating about books like yours that includes so much great history of Harlem is that they introduce me to or remind me of important people who were part of that era, and in your book one of those figures was the photographer James Van der Zee. Can you talk a little about how he fits into this story?

MSC .Yes. I looked very hard to see if I could find a link between the young Romare Bearden and James Van der Zee, but I couldn’t find a direct one. Van der Zee had a successful photographic studio in Harlem and was that ubiquitous photographer who was there to photograph everything – the street parades, the Marcus Garvey pageantry, the weddings, the funerals, the social organizations, the salons – you name it, he was everywhere. In the course of his work, Van der Zee produced what is probably the most complete visual survey of Harlem from 1919 all the way up until World War II. So, while there was no obvious direct link between Bearden and Van der Zee, all of the life that Bearden was living in Harlem was being documented visually by this extremely artful photographer. But, I must say that Van der Zee was motivated as much by running a business and making a living as he was by his art, and he wasn’t famous during the time that he was taking the photographs, he became famous when the Metropolitan Museum of Art displayed his work in 1968. It was then that people saw the magnificent work he created as art, but while he was there in Harlem, he was a photographer who had a photographic studio.

JJM .We take pictures so indiscriminately now with our digital phones, and we take the technology for granted, but photography was monumental technology during Van der Zee’s time, and, as you write in your book, “photographs were the visual evidence of progress from slave to contributing citizen.” So, as you say, Van der Zee’s priority at the time was in making a living, but in retrospect what he was doing was cataloging the progress of the African American in Harlem.

MSC .Absolutely. Regarding the photographic technology of his time, when I came to the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1977, we were in the process of acquiring a large portion of the Van der Zee collection– ( I think they still own the collection) – and what concerned us most is that much of his work was done on glass plates, silver nitrates, which are of course incredibly unstable. Of course the images have been transferred from those plates. So, yes, the technology has changed quite a bit!

JJM . When did Bearden begin to think he had an ability for creating art?

MSC .There are lots of stories that speak to when he started to think of himself as an artist. Certainly the story about his encounter with the frail, sick young man Eugene Bailey, who was incredibly skillful as an artist and who “taught” him to draw evoked in him an excitement about creating visual images. This was an important episode in his life because he repeats it over and over in his writings, which are now in the archives. There are other instances, such as the time he won a high school poster contest, but the first real evidence, in my mind, that demonstrates that this is something that he is taking seriously as a possible vocation comes from the masthead of the periodical connected with Lincoln University, on which it says “H. Bearden, Cartoonist.” This comes at the end of his first year at Lincoln, and he is identifying himself as a cartoonist. He then transfers to Boston University, and then transfers to NYU, and at both universities he assumes the editorship of the humor magazine as a cartoonist. He wrote a wonderful paper while attending NYU about how significant cartoons were in terms of social satire and social commentary throughout the history of visual arts. So he is clearly thinking of himself as a serious artist, but primarily as a graphic artist and a political satirist.

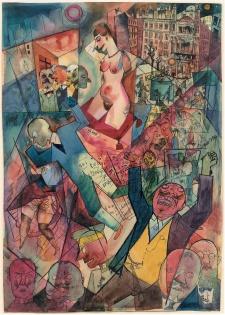

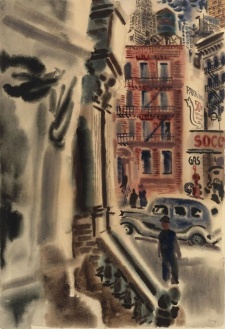

JJM . It was around this time that he was inspired by George Grosz, the German artist known especially for his caricature drawings and paintings of Berlin life in the 1920s who became one of his mentors. How did he inspire Bearden’s art?

A sampling of Grosz’s work

Untitled, 1919

“Der Agitator,” 1928

New York street scene, c. 1930’s

MSC Grosz has an interesting story. He had to leave Germany because he was such an honest and severe critic of the rise of fascism. In fact, when he left, his citizenship was revoked. He then came to the United States as a highly regarded artist, who, nonetheless, barely spoke English. He secured a position at The Art Students League in New York City. The Art Students League was a place where you could literally walk in from off the street as a novice artist and decide on an artist with whom you wanted to study. Bearden’s friend suggested to him that if he really wanted to be serious, he would need to have serious artistic training, so while he was still an undergraduate at NYU, found his way into Grosz’s studio at the Art Students League, probably because in Grosz he saw someone who was a master of drawing, but also because in his searing cartoons he saw Grosz’s ability to translate political ideas into visual images. I believe that was his initial attraction.

Once he got into Grosz’s studio, Bearden learned from him that he needed to study all the great artists going back through early representations in renaissance art, and that he needed to understand the fundamentals of painting and drawing: line, space, light, and composition. Grosz got Bearden to broaden his view of art beyond just doing cartoons. Apparently Grosz became very fond of him, had a nickname for him, and even let him lead the class at times. So, while Bearden didn’t study with him for long, the instances that he did were absolutely pivotal in his life.

JJM .One of Bearden’s political cartoons was controversial, concerning whether black men should serve in the armed forces. Did this come out of the influence of Grosz, and did that relationship give him the confidence to inject politics into his art?

Bearden’s cartoon from the Baltimore Afro-American, March 21, 1936

Captions for the five panels of the cartoon:

In ’17 the big boys told the colored soldiers to go fight for their country and if they did when they returned they would enjoy true democracy

So the colored boys marched away to help save the world for democracy

And dodged in and out of shellholes

While the big boys on the other side piled up the dough

So that when the boys got back many of them had to live this way. And soon they may be called on to go through this same thing again

MSC .Yes and no. Yes, because Grosz was an incredibly honest artist. He drew what he saw, and that quality of being candid and honest was something he introduced to Bearden. On the other hand, the sentiment that Bearden expressed in that cartoon had allies in Harlem who felt that the promise made to them during World War I that, if they fought and were heroic they could come back and be recognized as being part of this great democracy, was not realized. Instead when they came back there was one racial riot after another. So, there was a fairly significant sentiment expressed for those who were politically left-of-center – that perhaps African Americans should think twice before serving in World War II.

JJM .In addition to Grosz, who were his earliest artistic influences and how did these influences manifest themselves in his own work?

MSC .In 1934 Bearden wrote a wonderful article titled “The Negro Artist and Modern Art” in which he makes a great effort to celebrate the Mexican muralists. During the Depression, several of the muralists – Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros among them – were in the United States in various places working, and Rivera,in particular, was a giant figure.

“Ford Motor Company River Rouge Plant” (panel), by Diego Rivera, 1932

“Girl with the Yellow Hat,” by Norman Lewis, 1936

“Blind Beggars,” by Jacob Lawrence, 1938

He had had a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art very early on, he was working on the murals at Rockefeller Center — which unfortunately the Rockefeller family didn’t like – as well as magnificent murals in Detroit, depicting laborers at Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant. The Mexican government was celebrating these artists who were modern painters who embraced a modernist ethos but who also embraced their heritage. Bearden thought that was exactly the approach that he wanted for himself, that he wanted to be part of the lineage of modern art that was questioning mimetic representation and verisimilitude . He was inspired to be part of all the revolution in seeing and painting, but he was also very much a race man in those days and he wanted to represent the issues of heritage and the issues confronting his people, and for him the Mexican muralists were the perfect models.

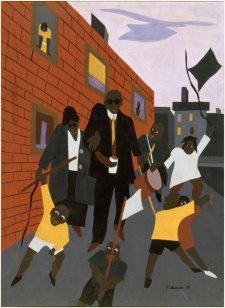

Also, after he graduates from college, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) is in full swing, supporting many qualified black artists and the easel projects of an artist like Jacob Lawrence were all supported by the WPA. Others, like Norman Lewis were instructors at the WPA arts center in Harlem. So, all of a sudden Bearden can see the work of African American artists in great numbers. Jacob Lawrence, for example, was producing substantial bodies of work, and that was a huge influence on Bearden. The artists seemed to be saying, “Look at us, we are an artistic community, we are very much a part of American art.”

JJM .During the Depression, too, many artists were using their art to expose social deprivation, and Bearden’s work during that time included scenes of, for example, men and women in breadlines, factory workers receiving pink slips, families gathering to partake of meager meals, and farm laborers. “The Family” is a great example of his early work. How was his work from this stage of his career received?

MSC .The artist who was receiving national acclaim was Jacob Lawrence, and frankly, at that time, in the 1940’s, rightly so. Lawrence had produced many series of paintings, including, in the early 1940’s, his “Great Migration” series, which was just epic, and so beautiful and brilliant that two museums fought for it – the Phillips and MOMA – and to this day, one owns half the series, and the other museum the other half, which is really crazy. But Bearden was recognized as a serious artist, and his piece “Factory Worker,” which was reproduced by Fortune Magazine, is probably one of the high points of his work from this period. While his name would be mentioned along with a dozen other names of significant African American artists, he wasn’t yet a standout.

JJM .What kinds of challenges did he face as a “Negro artist” involved in “Modern Art?”

MSC .He wrote an extraordinary article in 1946 called “The Negro Artist’s Dilemma,” and he is very clear and very lucid in his mind about what that dilemma is. He characterizes it by pointing out that black people were represented artistically in demeaning caricatures. He characterizes that type of representation as part of keeping the “Negro” in his place.

During and following World War II, he felt that confining himself to only representing black people was also confining him as an artist, and he didn’t want to be restrained in any way. He wanted to feel that as an artist he could choose to do whatever it was he wanted to do, which meant not anchoring his art to black people, to black subject matter, or to black themes. That was his first major change in his direction, and it happened during the war.

We now know that while he was an enlisted soldier he was beginning to create his first series, based on The Bible. After, when he came back home to Harlem, he went back to his studio above the Apollo Theater and worked on a series based on the Biblical theme of the Passion of Christ. The series based on that theme became a landmark show for him in Washington, D.C. This show was seen by a New York City art dealer who then brought Bearden into his stable of artists, which exposed Bearden to the New York art world – not just the Harlem or the uptown art world, but the New York art world. So, from his perspective, in 1946, here he is, a black artist, and he is painting abstract figurative paintings based on The Bible and classical literature, and this is what gets him into the New York art world.

JJM .Is there one piece of art that you could say that this is when he came of age as an artist?

MSC .The thing that I loved writing about this book is that I learned that he kept coming of age, and I loved following his temperament and the limits he outlines for himself. He was very good at being able to articulate what was challenging him. First it was his figurative work, then it was his abstract literary work, then he goes to Paris and returns without really working on anything definitive. He then has a nervous breakdown, and when trying to come back to painting, he stripped his painting completely of figures or anything that looks like it is representational and his work becomes totally abstract. That is a very prolific, productive period of his life, and the work that he does is absolutely gorgeous, where he is looking at color and texture and light and compositional elements. It is as if he just decided to become a master of all these abstract compositional elements of painting. Then comes the civil rights movement, a time when he is challenged once again. I really did love to see that movement, that constant re-invention. like his great grandfather re-inventing himself.

JJM . The collage work he is so famous for didn’t come out of the civil rights movement, but it was first publicly displayed during the time of the civil rights movement…

MSC .We now know that Bearden had actually been experimenting with collage for many years, before the movement really accelerated. At the time of the March on Washington, he and a group of black artists formed a collective called Spiral, and he actually took a bag full of clippings into a Spiral meeting in an attempt to get his fellow artists to work with him on a group collage, but they weren’t interested. He decided to keep this approach – which had been experimental – and keep working on it and working on it, until one of the Spiral members happened to visit him in his studio and, after seeing one of the pieces, suggested that Bearden photograph it and blow it up. He was doing the collages on a little piece of paper about the size of copy paper, and that is when he came upon this medium of the projections, which was to make a collage, take a photograph of it, and then blow it up. It gave these works an extraordinary immediacy that was almost eerie when you were in a room with them.

JJM .Women played a really prominent role in Bearden’s family, and they dominated his work from 1964 until his death in 1988. Would you mind talking just a bit about this, and perhaps you can describe what a “Conjur woman” is?

MSC .Bearden was surrounded by absolutely extraordinary women. His great-grandmother was the head of a multi-generational household in Charlotte, and his grandmother was a preceptor at Bennett College, and a dorm matron, a writer, and very well respected in her community. His mother Bessye was an absolute powerhouse in Harlem. Bearden grew up during the time when political allegiance on the part of African Americans was shifting from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party, but black Republicans still had a great amount of power and influence.

Bessye Bearden was a Democrat, and she worked like the dickens on behalf of her clubs and organizations to lure black voters to the Democratic Party, which was of course part of Franklin Roosevelt’s electoral success. She was also a journalist for the Chicago Defender from 1927 until her death in 1943, and was right in the middle of everybody and everything that was going on in the Harlem social and political world, and in her home, she held forth in a salon that attracted great people like W.E.B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, Andy Razaff, Fats Waller, who congregated in her living room. So, Bessye had real power – about as powerful a woman as you can imagine for that era. If she were alive now, with the type of power and influence she had, she would be the mayor of a big city, or a gubernatorial candidate.

Then, he married a woman who turns out to be the person who helps him out of his depression and nervous breakdown which gets him back to painting. She becomes his guide, shepherding his way forward. So, Bearden has always been around and been attracted to these incredibly powerful and creative women — including collaborating with (dancer and choreographer) Diane McIntyre, (playwright and poet) Ntozake Shange, and (writer) Thulani Davis.

Clearly he had a deep and profound comfort with women intellectually and artistically, which gets reflected in this “Conjur Woman.” The “Conjur Woman” is from black folklore, and was believed to have special powers – if you wanted revenge on somebody you went to the “Conjur Woman,” or if you wanted to heal you went to the “Conjur Woman.” She was magical, and he represents her in his art over and over again. He sees her in the “Odyssey” series in the figure of Circe, and he represents Circe as a type of “Conjur Woman.” This “Conjur Woman” becomes emblematic of what he believes is some sort of profound, slightly mysterious power that women have. There is also a theme of a regal monarch, so you see dignified women like Sheba sitting on her throne. While there is much of that, there are also these incredibly erotic and sometimes outright racy representations of women, so he saw women as extremely multi-dimensional.

JJM .How did the developments in jazz, particularly with the emergence of bebop – which was simultaneous with the literature of Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin and Albert Murray – affect the way he thought about his art?

MSC .Ellison and Bearden were friends, but Albert Murray and Bearden were very close. They saw each other all the time, and Murray and jazz became quite influential because he felt that Bearden’s work was a combination of laying down a very disciplined grid on which he would then improvise many of his compositions, which is a way of working very influenced by jazz.

Also, when Bearden was coming of age as an artist in Harlem in the 1930’s, he was a devotee of jazz – he went to the night clubs, he hung out in “Jungle Alley” in Harlem, and he knew the music, the musicians and he immersed himself in their artistry and mastery. He did not realize how extraordinary an experience it was until much later in his life.. While his appreciation of the experience of being with these brilliant artists may not have come until later, there is no question that he came to understand the impact of their music on his work.

JJM .What are three important pieces of his that you would recommend to readers that best exemplify his work?

MSC .Any one of his projections are a must to see. The Studio Museum in Harlem has the “Conjure Woman,” which is probably one of the best. Secondly, his public art is quite spectacular. Bellevue Hospital in New York, of all places, outside of the second floor chapel, houses his masterpiece, “The Block.” Lastly, he completed two autobiographical series and the works from those series are stunning, intimate and honest. The High Museum in Atlanta has a self-portrait that he completed that is a major piece in the second autobiographical series.

JJM .Where can readers go to see a prominent or extensive Bearden collection?

MSC .The Mint Museum in Charlotte almost always has a significant selection of Bearden paintings and collages on view. The city also is home to Bearden Park, a five-acre memorial to him. That said, there is almost always a Bearden exhibition at some major museum. This fall, for example, the High Museum will mount an exhibit that focuses on his autobiographical series.

JJM .What is Romare Bearden’s artistic legacy?

MSC .I think his legacy keeps growing, and it has been pretty astonishing. The most telling example of that is that for the 100th anniversary of his birth, which was 2011, many museums around the country held Bearden events. The Studio Museum in Harlem chose to honor him by asking artists who had been influenced by Bearden to select a work of his they would then put on display. They had two separate shows that were really enlightening in terms of the impact that he has had on so many different artists, from Wangechi Mutu to Kerry James Marshall. His boldness, and his craftsmanship in working with the materials he embeds in his collage is impeccable. The kinds of cultural or visual clash and disruption that he would sometimes embed in his collage could be so surprising and so unpredictable.

What I loved about Bearden is that he was unpredictable; he didn’t do things over and over and over again. I believe artists today see that he exhibits a certain freedom, a certain exhilaration, a certain unwillingness to censor himself or to make himself palatable to somebody else’s vision. His imagination was always alive.

.

________

.

.

“Profile/Part II, The Thirties: Artist with Painting and Model,” 1981

.

“The Block,” 1971

.

.

____

.

.

An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden

by

Mary Schmidt Campbell

.

.

This telephone interview took place on January 17, 2019, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita. With gratitude to the author for making herself available, and to Oxford University Press.

.

.

.

___

.

.

.

# Text from the publisher, Oxford University Press

.

.

.