.

.

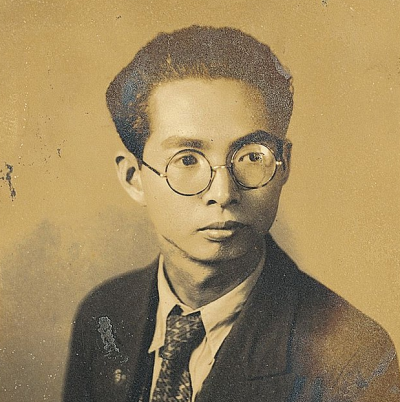

Maria Golia, author of Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure, beside a tribute to Ornette Coleman

Fort Worth, Texas; 2016

.

___

.

….

…..Few figures in jazz music impacted the world of creative art quite like Fort Worth, Texas-born Ornette Coleman. The eminent jazz critic Martin Williams – an earlier admirer of Coleman’s – prophetically wrote in the liner notes to Ornette’s 1959 album The Shape of Jazz to Come that what Coleman is playing “will affect the whole character of jazz music profoundly and pervasively” and that “when we hear him he creates for our ears, hearts, and minds a new sensibility.”

…..Less than a year later, in the liner notes to Change of the Century, Coleman wrote that there is “no single right way to play jazz,” and that “the members of my group and I are now attempting a break-through to a new, freer conception of jazz, one that departs from all that is ‘standard’ and cliché in ‘modern’ jazz.” This philosophy and the astounding, adventurous music he created served to continually challenge the skeptical status quo, and made him a guiding light of the artistic avant-garde throughout a career spanning seven decades.

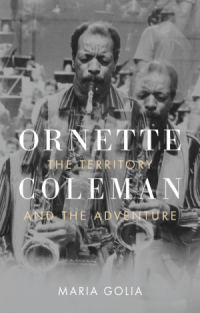

…..In the introduction to her compelling and rewarding new book, Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure, Maria Golia writes that the book is “more a compendium than a comprehensive biography or technical analysis,” one that “helps contextualize Ornette’s work”–work that broadened the artistic horizon and changed countless lives.

…..The book’s focus is on “pivotal places, people and struggles” during Ornette’s life; his exposure to the music culture that existed in Fort Worth during his youth; his music-driven trajectory from Texas via New Orleans and Los Angeles to New York; his homecoming and the weeklong inauguration at the Caravan of Dreams, Fort Worth’s “palace of the avant-garde”; and concluding with Ornette’s “trains of thought regarding musical methodologies and his attitude toward language, painting, women, celebrity, teaching, and death, tracking events in his later life.”

…..In an April 24, 2020 telephone interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Ms. Golia – from her home in Cairo, Egypt –talks about her book, and the artist she describes as “self-taught and proud,” who had a “nonconformist approach to music that attracted ridicule and censure” and who “used music to advance his self-understanding and in doing so, expanded the musical boundaries of the known.”

…..

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

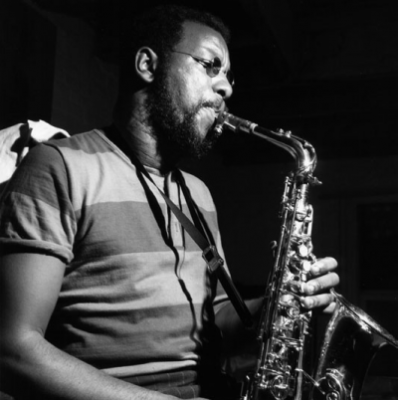

photo by Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images

Francis Wolff’s photograph of Ornette Coleman during rehearsal for his album The Empty Foxhole

New York City; September, 1966

.

.

“The music we are trying to play is no more abstract than most modern paintings…It’s just music in which we have tried to get together and play and use our emotion and intelligence [as] far as we could carry it…I have tried my best to become as – maybe you could use the word “free” – I really call [it as] complete [as possible]…”

-Ornette Coleman, in a February, 1960 WBAI radio interview with Gunther Schuller

.

.

.

Listen to Ornette Coleman’s 1959 recording,.“Tomorrow is the Question” (with Don Cherry, Percy Heath and Shelly Manne)

.

___

.

JJM How did you come to live in Cairo?

MG I am from New Jersey, and after dropping out of college I decided to travel, spending a lot of time in Europe, then ending up in Egypt in 1980. After five years I returned to America, which is when I started working at the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth, Texas. While there, I decided I wanted to become a writer, and chose to return to Egypt because it seemed like the best place, given my experience here, and also because it was a pretty inexpensive place to live at the time. So I came back in 1992, and I did become a writer. I didn’t finish my first book until 2004, when I was in my forties, so I was a bit of a late bloomer.

JJM What was the book?

MG My first book was about the city of Cairo, and the second book was about photography and Egypt. I wrote those books to download, in a way, what I had learned here, but also to top off my knowledge of Egypt’s history. Understanding Egypt was my big focus, and I also did a lot of journalism, social commentary and speech writing.

JJM Is this your first biography?

MG Yes, although I didn’t think of it that way when I set out to do it. There are various reasons why I decided to write this book, but in terms of approach, I did a lot of reading, and most of it focused on Ornette’s technique and how it compared to different styles of playing. John Litweiler’s A Harmolodic Life gives a lot of biographical details, but it’s sort of telegraphic, more focused on things like where and when he played, and how a show was performed or a record received. I knew something about music thanks to my recently deceased eldest brother, Frank, who was a composer and a drummer who studied with Elvin Jones, who I got to meet back then. I studied piano but I’m no musical expert, so the question was what could I contribute to the understanding of Ornette? I’m into research, and I knew Texas and a little bit about New York, so I decided I could offer context about the people and the places that influenced Ornette’s life, and, by extension, his music.

JJM Ornette grew up in Fort Worth, Texas. When I think of that city’s musical heritage what mostly comes to mind are the blues and country western music and, perhaps unfairly, an impression that it was not a musically progressive city. How did growing up there shape Ornette’s experience with music?

MG Fort Worth was really alive with music, which was a discovery for me. It was a stopover for all kinds of musicians, big regional and national names, and several black neighborhoods had hot club scenes. Many great musicians came out of Texas, so there was a lot going on, and Ornette grew up in the midst of it.

The neighborhood he grew up in was close to one of the strips where a lot of music was being played, and in places that are famous, or should be famous. For example, a “who’s who” of jazz played the Jim Hotel, including Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald, and great rhythm and blues and blues artists played there as well. So, great musicians came through Fort Worth, but Fort Worth also produced them – Ornette is only one of them. Others included his good friend John Carter, who was a composer and clarinetist, the drummer Charles Moffett, the great saxophonist Julius Hemphill, the reeds player Prince Lasha, the saxophonist Dewey Redman, and King Curtis Ousley, who played with Aretha Franklin and then went the R&B route. All of these guys were not only from Fort Worth, they all went to the same high school, I.M. Terrell, the only black high school for miles around. So, it was a very happening music scene when Ornette was growing up.

JJM And this music scene was inspirational for him…

MG Music was all around him, and it was an important part of black community life, starting with church music, and everyone tried to get their kids music lessons because it was a way of offering them a cultural education. Many of the kids ended up in the school bands and the church bands, and Ornette was in both. He didn’t take lessons when he was growing up, but his father sang in a quartet, and they had a lot of musical friends. His mother Rosa wasn’t really down with the idea of Ornette playing music, but that was after her husband had died and she lost her first son and a younger daughter. Ornette’s sister Trudy’s sang in a blues band, which Rosa was not happy about because of the negative connotations associated with the places in which it was played, usually involving booze and gambling.

JJM Trudy had an impact on Ornette…

MG Yes, Trudy not only encouraged Ornette, she found gigs for him when he was a young man. He started playing professionally while in high school, when many of the older generation of musicians were off to war, and younger musicians like Ornette took their place. But his mother wasn’t very supportive; at one point Ornette mentioned that during a trip to Fort Worth in the 1960s he discovered all the records he had made until then and sent to his mother had never even been opened.

JJM As a young man he didn’t trust teachers and had a reputation for being different – an outsider and a rebel. How did he gain this reputation at such an early age?

MG For one thing he always wore an overcoat even when it was hot, and he kept his hair long and “conked.” He was an adolescent with attitude, which is what many of us were. But he was already quite serious about music He knew which way he was going and that set him apart from a lot of the other kids, but his friends were also all very serious about music and also went on to have influential careers.

JJM There is a famous story about him being expelled from school for playing the “Star Spangled Banner” inappropriately…

MG Right, this is part of the Ornette lore, but it is based on a true story, apparently, because I got it from people who knew him in Fort Worth at the time of the incident. He was part of the I.M. Terrell High School band that played in regional competitions. High school bands weren’t just for half time on the football field, it was a big deal to be in a band, and some of these bands practiced hard and were excellent. They were formative features of a lot of these musicians’ careers, not just in Fort Worth, but all over America, and this was certainly the case for Ornette.

The story is that Ornette had a problem with the band leader, who was a very exacting guy who didn’t like the way Ornette dressed, so they rubbed each other the wrong way. During a Sousa march, Ornette apparently improvised some riffs outside the score, causing him to get thrown out. That’s the story, but the way they tell it in Fort Worth is that it wasn’t Sousa but the “Star Spangled Banner” they were playing, which raised it to a new level of rebellion. But as I point out in the book, to be a rebel, in a kind of counterintuitive way, made him a real Texan. There was this notion of individualism, which is a bit of a self-myth in some ways, but in Ornette’s case it was real.

JJM You also wrote about how early in his career a club owner fired him for the way he played “Stardust”…

MG That was when he was playing with his mentor, another Fort Worth musician named Red Conner, who by all accounts was an extraordinary saxophonist. Ornette was about 18 and just getting into bebop, and this instance of playing “Stardust” was sort of his epiphany because he was playing all the changes the way he was supposed to play them when he suddenly just stops the chords and plays outside or around them. He described it as having mastered the chords, allowing him to leave them behind and go someplace else with the music. This didn’t go down very well, and he got fired, but Ornette was always getting fired, and musicians who played with him would walk off the stage when he started doing these things. Some musicians dissed him, and he had a terrible time being accepted, but one of the great qualities of Ornette was that he didn’t care. He learned to accept rejection as almost a badge of honor. Along these lines, he once told Don Cherry that no matter how much you get rejected, you just work even harder, which is good advice for any artist.

JJM He spent six months in New Orleans and musicians there didn’t like the way he played. You wrote that “he grew a thicker skin. Rather than rejection, Ornette began to see it as natural selection.”

MG When he got to New Orleans, he had just come off of his first traveling gig, which was with a vaudeville minstrel band, and since it was 1948 it was kind of a throwback. He got to play a few bars of blues every night, and that would be about as far as it would go. He got fired from that gig, got beat up in Baton Rouge, and somehow made it to New Orleans, feeling battle worn by the time he got there. He did make some friends in New Orleans – that’s where he met the drummer Ed Blackwell, who was willing to experiment with music and play the way he wanted to play. They were separated for a time but then serendipitously hooked up in Los Angeles and ultimately became close collaborators.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1959 recording of “Lonely Woman” (with Billy Higgins, Charlie Haden and Don Cherry)

.

JJM Ornette said “I didn’t need to worry about keys, chords, melody if I had that emotion that brought tears and laughter to people’s hearts.” Emotion played a big role in his musical philosophy…

MG When Ornette spoke about emotion, I believe what he meant was emotional intelligence. He recognized how feeling influenced people’s behaviors, but it influenced thinking as well, and thinking and emotion are two different things. Emotion is very fast, but thought takes more time, and he wanted to distinguish one from the other. He was gifted with a lot of emotional intelligence, which all great musicians and artists probably are, but for him, when he speaks about turning emotion into knowledge with his horn, he was interested in ways of acquiring knowledge. He had trouble in school because they would teach very formally, and he didn’t go for that way of knowing, he was looking for more direct and intuitive ways of learning.

JJM What fed his conviction that rhythm, melody, and harmony were of equal value and that every instrument could serve them equally well?

MG This again ties into his character and his perspective, and Ornette liked and was attracted to complexity, and the reality of many things happening at once, not just in music but in life. He once made an observation about being on the street and watching some guy get into his car, while at the same time somebody is calling out to someone else, and in a window someone is blowing a whistle, and that all of these things are a facet of a moment, and this idea of many things happening at once fed into his music. A lot of people who understand music talk about what a great ear he had, and how he thrived on complexity – how well he could hear things and identify patterns and follow trends of musical thought while he was playing.

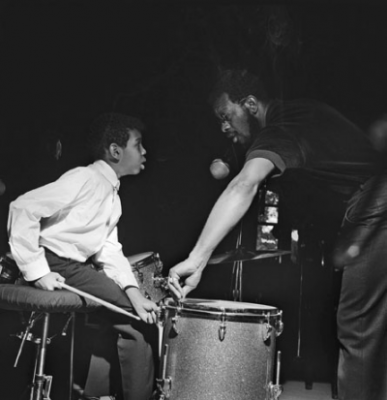

photo by Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images

Francis Wolff’s photo of Ornette Coleman with son Denardo at The Empty Foxhole session, Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey; September 9, 1966

Since he liked the idea of everything happening at once, that is partly why he saw rhythm, melody and harmony as having equal value, but it is also because he was very down on the idea of ego-driven music, where an ensemble is there to showcase the leader and back up the soloist. He wanted everyone to “come out with it” whenever they liked and, in essence, be an equal opportunity improviser. It’s not that he didn’t distinguish between rhythm and melody and harmony, he just felt they all had something to say and that there didn’t have to be a fixed way for saying them. For example, drums are typically thought of as a rhythm instrument, but Ornette appreciated drummers who used them melodically as well. As in everything he did, he tried to break down the boundaries and limits musicians encounter when they set out on the adventure of playing music.

JJM Ornette always had a strong woman in his life, including – and especially – his first wife, the theater director, poet and civil rights activist Jayne Cortez. How did she contribute to Ornette’s desire to create music that defied categorization?

MG Well, I think they had a lot in common. She was also a non-conformist, stood up what for she believed in, and spoke out about injustice. She was very smart, very talented. She started out writing at a very young age, and she also had a musical background. She listened to a lot of jazz and was very much into bebop.

Ornette had to have admired her. When you are young and you find someone like that, you develop ideas together, and you play off of each other the same way musicians do. So I think they shared values. For example, she was very much into theater and while directing a Jean Genet play for the Watts Theater Ensemble – according to Stanley Crouch, who worked with her on this – she felt that everyone on the stage contributes, that it is not just one person in the spotlight. So she and Ornette had similar ideas about ensemble and about how you create art, the participatory aspects of art production and the role of the individual within the collective. Also, she liked his music, and she seemed to Ornette smart enough to appreciate it.

.

Listen to the 1959 recording “Change of the Century” (with Don Cherry, Billy Higgins and Charlie Haden)

.

JJM Ornette was controversial, and a polarizing figure among musicians. At the time of Ornette’s famed 1959 Five Spot performances, Miles Davis said that “the man is all screwed up inside, just listen to what he writes and how he plays,” and the pianist Red Garland accused him of “faking” and being “unfair to the public.” Conversely, many critics liked his music from the outset, Martin Williams and Nat Hentoff among them. Who were some contemporary or elder musicians who understood and appreciated Ornette from the outset?

MG It is important to understand that Ornette was a threat to the status quo, and a threat to many of these great bebop musicians, though by that time people like Charles Mingus and John Coltrane were already moving the music in different directions. He was a threat to a lot of musicians because it was as if they had to suddenly throw out everything out that had been seen as standard achievements in order to do something completely different, and they understandably didn’t like that.

But there were musicians who were seekers like Ornette and could relate to how he was playing and what he was trying to do. Sonny Rollins was an established and admired musician – a big, strong, buff guy who was a hero to a lot of the musicians – and was open to new ideas, and his interest in Ornette was encouraging to him. There is a beautiful story in Litweiler’s book about the two of them playing together on a Pacific Coast beach with the pounding waves as their rhythm section, feeding this idea of companions in search of where music can take them. Coltrane was also an established musician by the time Ornette played the Five Spot, and he recognized something in Ornette that he could learn from, and that modesty endeared him to Ornette not to mention that Coltrane was a great affirmation for Ornette, because he appreciated what Coltrane was doing as well.

JJM You wrote, “Ornette’s opening night at the Five Spot is probably the most widely reviewed, referenced, and recollected in jazz history, eliciting some of the most colorful and contradictory descriptions in the annals of premiers at large.” The critic A.B. Spellman wrote that he arrived at the Five Spot as a “myth.” Because the club’s owner Joe Termini was unsure of how the public would respond to Ornette, he hired Art Farmer’s Jazztet to play on the bill in case Ornette bombed. The critical reaction to his performance was mixed. What expectations did Ornette have for this engagement?

MG He knew that New York was the place to be and to be heard, so he knew this was a big step for him. His first two albums were out, and the Downbeat issue reviewing the latest one was on the newsstands, and, New York was New York, so there had to have been some degree of excitement. At the same time, he had been so batted around and marginalized by this time that he was probably braced for whatever happened, and what actually did happen was this tremendous storm of controversy that arose around his quartet. I so enjoyed going back through all of the reviews from the Five Spot debut and the early years of Ornette’s career because everybody was trying to figure out what the hell is going on with this guy, and some of them were absolutely enchanted, and some of them were totally appalled, but either way, they were really stretching to express themselves, and it made for some great reading. I tried to include a lot of that in the book to give a sense of the furor that was aroused between the critics and some of the musicians when Ornette and his quartet hit the scene, because it was so indicative of the time, and it wasn’t just Ornette, it was also Don Cherry, Billy Higgins,and Charlie Haden—and they were all quite young..

JJM Ornette became a demarcation point for critics – if you liked him you were considered progressive, if you didn’t you were considered “square.” Leonard Bernstein called Ornette “the greatest thing that ever happened to jazz.”

MG Ornette really challenged the critics to express what they thought about music. He challenged critics’ preconceptions in the same way he challenged musicians’. The critic John Rockwell told me that a scene happens when the critics pay attention, and Ornette was like a red flag to a bull, everybody was paying attention. But how wonderful that Ornette’s music could ignite so many conversations and opinions and thoughtfulness that translated into other means of expression. He had a big influence on writers but also on art, music, dance – all interwoven in those days – when all kinds of conventions were being broken, and when all these disciplines inspired one another. This cross-fertilization of the arts is why you can’t take the jazz scene of the time on its own, it was part of a bigger movement of breakaway art.

JJM Allen Ginsberg wrote about how improvisation was the important thing that was happening in the arts at the time, and that jazz was the center of that, it was what artists looked to…

MG Yes, because people were looking for other ways to interact,and jazz was that sort of art form where the ensemble is there, not to showcase or subsume the individual, but to offer the individual the maximum opportunity for expressing him or herself as part of the ensemble. There was a sense of the collective in the arts, and also, literally, there were art collectives like the loft scene that was geared toward people producing their work in outside of the more established, “commercial” system.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Ornette Coleman’s 1973 piece “Midnight Sunrise,” recorded with the Master Musicians of Joujouka

.

JJM Ornette took two trips overseas that were especially impactful for him, the first being one to Europe, right around the time his album Free Jazz had been released. How was he received in Europe at that time?

MG This was the mid-1960s, when the idea of breaking with artistic convention was happening in Europe as well, with writers like Samuel Beckett, and literary journals like New Departures which started producing concerts called “Live New Departures” all over Great Britain, with poetry readings combined with experimental and electronic music. With so much experimentation going on Ornette was welcomed as an innovator, and he was admired and appreciated. So the time was right in the same way that the time was right when he hit New York. Timing was everything. If he had come too soon he would have been marginalized the way he was before, and if he had come a little later it wouldn’t have been a big deal because everyone was looking for ways to break with convention in the arts. So this was very congenial to people in Paris, London and Scandinavia. He toured widely and had great audiences. There was a great openness and appetite for the new at that time and he was a part of that.

JJM The critic Victor Schoenfeld wrote at the time that “from this time, jazz musicians will have a more direct access to European musical culture.”

MG Ornette wasn’t the first jazz musician to spend time in Europe – there is a long tradition of that – but there was a lot of openness, and he brought the wave of excitement of this new approach with him, and it was affirmation for like-minded musicians in Europe. Music always crosses national boundaries so there was already a lot of interplay, but I think Ornette helped sew the international avant-garde together.

JJM The other trip was to Morocco, which was clearly a life-altering experience for him…

MG Oh, definitely. His friend, the great music writer Robert Palmer, turned him on to the village of Joujouka in Morocco. Palmer got there through the painter/writer Brion Gysin, sidekick of the writer William Burroughs, who were both there when Ornette went in 1973, and the idea was to record with musicians from Joujouka, who Palmer had made tapes of and played for Ornette. Joujouka players are mountain people, mostly flautists playing a very traditional music that has religious and magical overtones.

Joujouka is a little backwater mountain village of goat and sheep herders and farmers, but the musicians were part of this cultural tradition. A large group of musicians of all ages got together and played wind instruments, drums and violin, and Ornette was very impressed with the austerity of the place. He particularly admired how the instruments weren’t tuned to the western scale, yet they achieved a dissonant unison. This goes back to the idea of multiplicity – of many things happening at once yet all moving in the same direction. I think he found a lot of validation in Joujouka because he realized what he was after wasn’t so new after all – it was something that long existed, had a purpose and a particular appeal. It was also an opportunity for him to play with people that were culturally ostensibly very different, yet he found commonality with them. So he discovered commonality in this faraway place that I think thrilled him and certainly validated his musical project, and gave him a sense of being grounded in something larger.

JJM Following his experience in Morocco, Ornette said, “I don’t try to please when I play, I try to cure,” and according to Robert Palmer, it gave him back his soul.

MG Yes, that’s right.

JJM Ornette had a great deal of respect from the world of rock and roll, and punk music in particular. What was his appeal to those musicians?

.photo © Brian McMillen

Ornette Coleman playing violin and trumpet in San Francisco; October, 1981

MG They liked him because he was a rebel and a nonconformist who believed in himself. He didn’t play by the rules – he made his own rules and was very much against formalism in music. He was an autodidact and respected that you could be a musician without necessarily having some kind of musical degree, and I think that was appealing to those players who were experimenting with self-expression through music. Other kinds of artists – painters, dancers, and even scientists – also admired him for his methodology that basically frees you of the constraints inherent in the social or commercial context, but also the constraints you create for yourself. He decided to play trumpet and violin for the same reason that artists switch to their left hand – he didn’t want to be tied to habit or trapped in practiced riffs. He didn’t want to repeat himself and was always looking for the new. This was someone who, from the start, played original compositions almost exclusively. These are the kinds of things artists and thinkers in a variety of fields are attracted to – a different approach that is not necessarily formal, yet requires discipline while also being intuitive. “Intuitive” is not my favorite word for this because it implies that it just comes by itself, and none of this came by itself for Ornette, he practiced and played and experimented constantly and endlessly. Everybody who ever played with him talked about how much energy he put into the process – not worried about results, but emphasizing and appreciating the process in art and in life.

JJM In the introduction to your book you wrote, “Reviewers wrote some of their most inspired prose when describing Ornette’s sound.” Was this also your experience when writing this book?

MG Definitely. First of all, I did a lot of reading and research, and noticed when people talk or write about Ornette they go out on a literary limb to describe his playing. And with somebody like Ornette, it’s not just the music that’s extraordinary, it’s the time and the place and the people and the surroundings. He was a true contemporary, in the sense of being both a figure and a shaper of his time. So, he’s a big deal, and if you want to wrap your arms around him you need to stretch.

I spent four years on the book, and it influenced how I think about writing. I had always chosen my subjects carefully because it requires living with them for several years, and they have to serve me as much as I try to serve them. With Ornette, I was singing with the angels, which means whatever I write about next will have to meet that same high inspirational mark. Ornette upped the ante for me as a writer, and I think he did that for many other writers as well.

JJM You worked in Fort Worth at the Caravan of Dreams, which was part of a major performing arts center built in 1983, subsequently closed in 2001. Was that experience an inspiration for writing this book as well?

MG That was certainly part of it. I got to hear and interact with many of the greatest musicians of our time during my seven years working there. But what actually happened is that I was living in Egypt during the time of the Egyptian uprising of 2011, when they overthrew Hosni Mubarak, the president for thirty years who I had written a great deal about during all those years of oppression. It was a historic time that reminded me of the 1960s. I was a little too young to fully understand the 60s, but that era was important to me because of the ideas that came out of it, and while I am sure I idealize them because it corresponds with my youth, it was inarguably a time of opening.

The revolution in Egypt went on for several years and it was a quite difficult time – there were many demonstrations, tension in the streets, and people being killed, and I was covering all of this news. The opening only lasted a second before it shut down, and while relatively predictable, it was hard to accept. At some point I just needed to escape it and give myself some mental distance, so I decided to write a cultural history of meteorites, which corresponds to my interest in science and space.

Until then, I’d only written about Egypt, but I had other interests and done other things in my life. For instance, I’m a fellow of the Institute of Ecotechnics, the people who invented the Biosphere2 project and were also behind the Caravan of Dreams. I attended annual conferences which brought some of the leading thinkers in various fields together, astrophysics, nanotechnology, genetics, planetary biology – you name it. So writing the meteorite book was a way of paying homage to pioneering scientists who dared to think outside the box, including those who maintained that meteorites came from space and impacted life on earth, facts that were long dismissed because they went against the prevailing theories. Writing about meteorites was a way of reawakening a sense of awe that I felt I’d lost. And while working on that book, I started listening to Ornette again. I hadn’t heard him for a while, and it dawned on me that everything that was important to me was wrapped up in this very awesome artist and original thinker that was Ornette Coleman.

So, Ornette presented himself to me as a way to revisit the 1960s and the American avant-garde, as well as the Caravan/Texas experience, mindful of the fact that when I worked at the Caravan, although I knew the music I knew nothing about the musicians, what they had been through, the obstacles that they had overcome, or their accomplishments. I accepted their greatness on face value, without knowing anything that had gone into it. Ornette gave me a chance to go back and fill the gaps in my knowledge of music history – especially Texas’s–that would make that lived experience more meaningful to me, while also sharing those stories with others. That was why I wrote this book.

JJM The story about Ornette opening the Caravan of Dreams is an essential part of your book…

MG It was a statement of intent to have Ornette open the facility. It was conceived as a progressive arts venue that would present theater, music, dance and art, and it did all of those things. As a maverick artist, Ornette was the perfect opening act – not to mention that it was his home town, and this event became a homecoming for him. That it was a successful opening did not necessarily reflect people’s taste in music so much as the excitement surrounding this beautifully appointed, performing arts center. But it should also be said that Fort Worth produced some very avant-garde musicians, and all of them were Ornette’s friends when he was growing up. However staid one might perceive Fort Worth now – or even then, for that matter, because let’s not forget that it was a segregated, very restrictive society – it produced some really great musicians perhaps because of that very kind of oppression.

The Caravan also saw art and especially music as a way of getting Fort Worth past the racist, “country” tropes associated with it. There was a lot of well-articulated intention behind the project and what its possible outcomes could be in terms of driving the development of art while reviving this sort of moribund city center, not just in real estate terms but also in cultural ones. Ornette was at the center of these intentions because of his Texas origins, the musical history to which he belonged, and the values his work embodied.

.

___

.

“Making music is like a form of religion for me, because it soothes the heart and it increases the pleasure of the brain…my real concern for the things that I would like to perfect in music is to heal the suffering, the pain…music seems to be a very good dose of light that can cause people to feel much better.”

-Ornette Coleman

.

.

photo by Francis Wollf © Mosaic Images

Francis Wolff’s photo of Ornette Coleman during The Empty Foxhole recording sessions

Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey; September 9, 1966

.

.

Listen to the 1985 recording of “City Living,” made during the performance that inaugurated the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth, Texas

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure

by

Maria Golia

.

.

Click here to read the introduction to the book

.

.

___

.

.

.

Maria Golia beside a tribute to Ornette Coleman

Fort Worth, Texas; 2016

.

Born in New Jersey and residing in Egypt,.Maria Golia.managed the Caravan of Dreams Performing Arts Center, one of America’s most progressive arts venues (1985-1992), in Fort Worth Texas, Ornette Coleman’s home town. Author of several non-fictions for Reaktion Books (UK), including .Cairo: City of Sand.(2002);. Photography and Egypt. (2010) and .Meteorite: Nature and Culture (2015), she is Middle East reviewer for the.Times Literary Supplement.and contributes to a variety of publications concerning Egyptian affairs. She is currently working on .A Short History of Tomb-Raiding in Egypt, to be published by Reaktion in 2022.

You can visit her website by. clicking here

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on April 24, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

Thanks to Michael Cuscuna and Brian McMillen for kind permission authorizing use of their Ornette Coleman photographs published in this interview

.

.

.

.

.

One comments on “Interview with Maria Golia, author of Ornette Coleman: The Territory And The Adventure”