.

.

photo by Francesca Patella

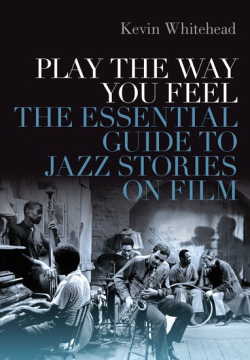

Kevin Whitehead, longtime jazz critic for NPR’s Fresh Air, and author of Play the Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film (Oxford)

.

___

.

…..As Kevin Whitehead points out in the introduction to his wonderfully entertaining and comprehensive book, Play the Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film, jazz music and the movies are “natural allies,” both growing out of existing creative traditions. “Jazz coalesced out of blues, ragtime, field hollers, spirituals, and brass band music just after 1900, around the time the spectacle of moving pictures was evolving toward storytelling. Early synchronized sound films in the late 1920s were likewise amalgamated from creative borrowings: part staged theatrical, radio play, and variety show.”

…..At the time these arts were growing in popularity, sound recording had advanced – the first jazz recording was 1917 – and movies with sound would appear ten years later, with The Jazz Singer, a film that was not so much about jazz as it was an early template for jazz stories to come; a clashing of parent and child about the embrace of this new, rebellious, and culturally complex music.

…..As time and technology advanced, so did the music and film, and the stories they tell together. Jazz musicians became cultural icons, and the films starring them – and about them and their art – would tell stories about, Whitehead writes, “child prodigies, naturals who pick up the music the first time they hear it, hard workers with a painstaking practice regimen, talented players diverted into soul-killing commercial work, and even non-improvisers taught to fake it.”

…..Whitehead’s book explores an abundant library of films – over 100 movies with jazz stories that cut across diverse film genres, including origin stories and biopics; spectacles and low-budget quickies; comedies, musicals and dramas; and stories of improvisers and composers at work.

…..In a December 14, 2020 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Whitehead talks about his book – a delightful guide for jazz and film enthusiasts.

.

At the conclusion of the interview, readers will find an extensive YouTube playlist Whitehead put together that features footage (and in some cases the entire movie) of virtually every film he discusses in his book.

.

.

___

.

.

“In charting how movies tell jazz stories, Play the Way You Feel connects examples over time, spotlighting a few endlessly varied themes. Black musicians educate white ones, who then play their feelings, expressing themselves in subterranean venues; cats of any color would rather fight than compromise their art. Jazz occasionally clashes with classical music, rock, or pop. Where people or styles are in conflict, a climactic (Carnegie Hall) concert may help sort things out.

“Looking at features and a few shorts, spectacles and cheap independents, the good, bad, notorious and overlooked, we seek to illuminate how jazz and its people are regarded in American culture and how filmmakers depict jazz subculture.”

-Kevin Whitehead

.

.

___

.

.

Watch Al Jolson perform ‘Toot, Toot, Tootsie!’ from The Jazz Singer, the classic 1927 film that Kevin Whitehead describes as a “template for a half dozen jazz stories to come,” a film that “points the way for other jazz films as the original backstage musical, broadly defined: a story in which the characters are performers who have reasons to break into song…and where a performed song’s lyric may (often by happenstance) reflect a singer’s own emotions.”

.

.

JJM What was the first movie about jazz that you ever saw?

KW I don’t know the answer to that. I do know that the first one that really grabbed me was the Martin Scorsese film New York, New York. I saw it when it was re-released in the early 1980’s, in an expanded version which was better than the original shorter version. I saw it as an elegant essay about art versus entertainment since the Liza Minnelli character was so clearly representing the latter, and Robert DeNiro the other. That was probably the first film that got me into it. As a film reviewer in the 1980’s I saw ‘Round Midnight and Bird, and that’s when I started to think that maybe there was an idea for a book somewhere down the line. I made a “want list” sometime around 1990 of a bunch of films with jazz topics, so I was already pretty deep into it by that point, but such films were of course much harder to find at that time than they are now.

JJM What is your background with jazz and with film?

KW I started writing about both at around the same time. I began freelance writing in 1979, when I was 27 years old. I was already interested in jazz and was writing about it a little bit for a weekly paper in Baltimore, which at the time was a traditional way for young writers to develop their craft while making very little money. My editor there asked me if I was interested in reviewing some movies, and since I went to the movies I thought I knew a little something about them, but realized I would have to educate myself in that area pretty quickly. So I was already writing about jazz when I got more involved in films in the 1980’s and finally felt like I needed to make a choice between one or the other, and decided that I wanted to write about jazz full time. I had been living in Baltimore at that time, and then I moved to New York in 1989, where I got heavily immersed in the live music scene.

JJM You are also a musician, right?

KW Kind of, but I am a good enough critic to know that I am not a very good musician. I enjoy playing, I like hacking around with my friends, but I make no claims for my playing itself.

JJM 1989 must have been a good time to be a jazz fan in New York. A great club scene, of course, and The Knitting Factory was around…

KW Yes, but when I arrived people were already complaining that it was past its peak. I spent more time there than anywhere. I was a real fixture at the Knitting Factory for the remainder of the time it was on Houston Street, until 1994. After it moved it wasn’t quite the same for me anymore. I then moved to Amsterdam and was over there for four years, so my life changed quite a bit at that point.

JJM What made you want to write this book?

Kevin Whitehead’s Why Jazz (2011) is described by its publisher (Oxford) as “a concise yet broad history of the music”

KW I was trained in literature, so I am interested in narratives and storytelling. Part of my interest was that I would see these jazz movies and feel as if other people were not picking up on some of the things that I was – that “art versus entertainment” thing in New York, New York being a good example. I was already thinking about a book like this in the early 1990’s, and then I met Krin Gabbard, who told me he had just written a book about jazz and the movies called Jammin’ at the Margins, which is a good book that I learned a lot from, but I could see his viewpoint was different from my own. He addressed these films from a more psychoanalytic viewpoint, and I was more interested in them from the standpoint of jazz history.

I kept the book in the back of my mind, and as time went on I wound up in the 2000’s teaching at the University of Kansas, where Tom Lorenz in the English Department encouraged me to teach a course on jazz film and literature. It was at that time I started getting back into it a bit and realized there are more jazz films than I knew about. I really started diving into the writing in 2013, after I’d left Kansas, and worked on it for five or six years before it was ready for publication.

Much of my initial time was spent on just finding films, but by the end of the process it was so much easier. My friend Chuck Stephens, a film critic and historian living in Los Angeles, was able to find some hard-to-locate films for me. He was a huge help to me for this project. At a certain point I decided to write about all of the English-language movies I could find that take jazz as some kind of a subject. I didn’t want to deal with films that had jazz soundtracks because I didn’t really have that much to say about them except to point out that they exist – I was much more interested in jazz stories. The more I got into it, I was surprised about how many there actually are. When I started I would have guessed there were a couple of dozen or so, but by the time I was finished I had written about 100 films, 60 or so that really take jazz as a subject, and another 40 where there are scenes or episodes in the film that resonate with jazz in some way that I also wanted to discuss. The famous “Elvis listens to jazz” scene from Jailhouse Rock is a good example of that.

.

A video interlude…Watch a clip of Bessie Smith singing “St. Louis Blues” from the 1929 film of the same name. St. Louis Blues was her only film.

.

JJM Jazz and film came of age together. How did Hollywood respond to the artistic and technological challenges created by this new popular music, and the simultaneous advancement of sound and film?

KW The immediate problem was how to record and film the music. The original process was to simply film and record the music live on the set, as in the two 1929 shorts directed by Dudley Murphy, St. Louis Blues with Bessie Smith, and Black and Tan with Duke Ellington. It was likely Paul Whiteman’s idea during the 1930 filming of King of Jazz to pre-record the music and then have the musicians mime on camera, resulting in good quality recorded sound. That became the norm afterwards in almost every film, with a few exceptions. Some of the music is recorded live on set in Shirley Clarke’s film The Connection, and also in All Night Long, a 1962 English film that is a jazz re-telling of Othello. Also, notably, in ‘Round Midnight, the 1986 film starring Dexter Gordon, all of the music is recorded live on set more or less the way they did it in 1929.

Hollywood has a tendency to remake jazz on its own terms, worrying less about getting it right than adapting the material to the Hollywood story mill. A few of the films I look at are ones where jazz is clearly a metaphor for another process, namely filmmaking. You see this in John Cassavetes’ Too Late Blues, in Damien Chazelle’s La La Land, Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues, and Scorsese’s New York, New York. There are discussions about artistic compromises in those first three films that could easily apply to filmmakers and the work that they do. You also see a way that, in biopics, the subjects of the films come to resemble the stars, so that Gene Krupa sort of becomes Sal Mineo in The Gene Krupa Story, and W.C. Handy becomes a singing, suave pianist like Nat King Cole in the Handy biopic St. Louis Blues, which Cole stars in.

JJM There are three things that are pretty consistent, especially early on, in movies about jazz; parental disapproval of a child’s interest in it, the clashing of jazz and classical music, and the third is the white appropriation of Black music. This in particular is a prevalent occurrence in, for example, the film New Orleans…

KW Yes, the whitewashing of jazz history is really extreme up until about 1960, when you start to see more Black jazz heroes appear on the screen. The independent film movement had a lot to do with that – filmmakers could take more chances with lower budget films. But it is true, even in New Orleans – which has Louis Armstrong and a version of what would become his All Stars, and Billie Holiday singing with them – the musicians are pushed aside and the film turns into a story about a casino owner and an opera singer. Yes, it is a bit shocking and you can sort of see Hollywood attempting slowly to make amends for this as you get into the 1950’s, when white musicians with Black musical mentors start to enter into the picture. You see an example of this in the 1950 film Young Man with a Horn—though there’s a hint of that in Syncopation eight years earlier.

.

A video interlude…Watch a scene from the 1940 film Broken Strings, in which a young violinist improvises his way to success.

.

JJM Many of the films you write about remind us of the challenges jazz and jazz musicians faced. Filmmakers were confronted with how to communicate that this complex music was created by Black musicians, which of course brought racism and how Hollywood portrayed it to the forefront. The record companies in the early days of recorded music had “race” divisions. What was Hollywood’s equivalent to that, and what movies were made specifically with a Black audience in mind?

KW An entire Black movie industry was going in the 1930’s, with Oscar Micheaux probably the best known of all the Black directors. He was extremely prolific, and I went looking into his body of work as best as I was able for stories that take jazz as a topic in some way, and I really couldn’t find anything – even his 1938 film Swing doesn’t really address it so much.

An example of a film made specifically with a Black audience in mind is Broken Strings, a one hour feature film from 1940 that was actually made by a white director and screenwriter, Bernard Ray, yet the film clearly has a strong African American identity to it. It features Elliot Carpenter and Clarence Muse, who was one of the great Black actors of old Hollywood, and who plays the father in that film. Matthew Beard, “Stymie” from the Our Gang comedies, is also in there, playing one of the young violin players. As a few jazz films are, Broken Strings is kind of a remake of The Jazz Singer, which is the original clash of generations and musical tastes movie.

JJM It’s a charming story. The father was a musician who had health issues, and he was no longer able to earn money for the family…

KW Yes, he is a classical violinist who is in a car accident and can’t play anymore due to a hand injury. He needs an operation but money is tight, so his son – who also happens to be his prize student – and his friend who plays the piano go out into clubs and play for tips. When his father finds out he is horrified as fathers are in these stories, and he forbids his son from playing jazz. At the end the son gets into a talent contest, during which two of his violin strings break so he can’t play the mazurka he intended to play, and he winds up improvising his way out of trouble. His father claps so hard that the problem that was seizing up his hand is cured and he can go back to playing the violin again.

Young Jeff (Ronnie Cosby) is welcomed by musicians played by Sam McDaniel (clarinet), Mantan Moreland (cornet) and Bud Scott (banjo), in Birth of the Blues

This is one of those films that involve young people playing jazz. I was a little surprised when I really got into some of the early films how often these child musicians turn up. In the prologue to the Bing Crosby film Birth of the Blues, for example, the Crosby character as a ten-year-old is sort of jamming with Black musicians down on Basin Street, and he is learning from them and they are learning from him. In the 1942 film Syncopation there are a couple of young musicians in there, including the Louis Armstrong figure at around age 10, playing the cornet. More recently, the 1999 film The Tic Code is about a young piano player who has Tourette syndrome.

JJM I found it interesting to see how these jazz stories progress with time. For example, you point out that by the time they got around to making The Glenn Miller Story with Jimmy Stewart, the film was nostalgia for swing fans…

KW It’s funny. Now we think of ten years as nothing in the evolution of popular music, but there were some serious changes between 1940 and 1950.

.

A video interlude…Watch the trailer to the 1956 film The Benny Goodman Story, starring Steve Allen

.

JJM I found your writing about biopics – biographies about jazz musicians, for example The Glenn Miller Story – especially interesting…

KW One of the things I had to grapple with regarding biopics was what is really true, and what isn’t. People often say they don’t care what’s true and what isn’t, but it is interesting to see how a true story can get thrown out in favor of a more familiar “Hollywood” story. That gave me an opportunity to look at ways in which Hollywood transforms these biopics into more familiar film narratives, which also involves – especially with 1950’s biopics – looking a little bit at the stories that the movies don’t tell. In particular, a biopic of W.C. Handy’s life could have been told completely different from the “last of The Jazz Singer remakes” that the 1958 St Louis Blues is.

JJM It’s tough to please jazz critics when it comes to biopics. There are plenty of examples of this, one being The Benny Goodman Story, which his biographers thought was a travesty and nowhere near the truth. You write about how filmmakers started using an “unreliable narrator” in biopics about thirty years ago…

KW Yes, it allows them a way to fudge the facts with a clean conscience. You see this going back to the Italian Bix Beiderbecke biopic Bix: Interpretation of a Legend, where the whole story is basically told by Joe Venuti, the notorious practical joker, which immediately calls things into question. From the same period there is also a nice episode from the TV show The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, where Indiana Jones relates the story of meeting Sidney Bechet, Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong, Elliot Ness and Al Capone back in Old Chicago in the 1920s. You also see it in the 2019 film Bolden, where the story is basically told from the viewpoint of Buddy Bolden after he has been in the state mental hospital for 25 years. The filmmaker is inventing the life of Buddy Bolden as much as all of the people back in New Orleans who were spreading ridiculous stories about the things that Buddy Bolden did in his prime.

One of the things that did surprise me about a lot of biopics is that they do actually get a lot right, even the much maligned ones like The Benny Goodman Story where there is a fair amount of accurate information stuck in there someplace, even if the overall picture is historically distorted.

JJM You wrote that the cinematic parallel to the jazz solo is the close-up. How so?

KW I attribute that idea to Stanley Crouch, who touched on it in an essay in the 1980s. He may not have even been the first to come up with it. If you look at the early talkies, you can see a lot of wide shots with four or five actors standing on stage together like you would see in a stage play, and I draw an analogy there to early New Orleans jazz, where everyone was basically playing together at one time. Then, around 1926, with Louis Armstrong and the Hot Fives you begin to see the cult of the soloist begin to develop, where the band falls away to focus on the soloist, and that seems like a pretty clear analogy to the close-up, how the camera zooms in on one actor on set. There are a few other analogies like that, like call and response and cross cutting, this back-and-forth dialogue, one to the other, in rhythm. Jazz and filmmaking are both rhythmic arts, and that ties them together a lot.

.

A video interlude…Watch a scene from the 1938 film Alexander’s Ragtime Band

.

JJM You wrote that “as jazz became a popular music, fans were curious about where the music came from. As jazz movies began to proliferate, filmmakers turned to origin stories.” What are the prominent films within these origin stories?

KW The first of them would be The Birth of the Blues, the Bing Crosby film from 1941, and then the following year comes Syncopation, which is a nice movie that only really started getting recognition from jazz scholars like Sherrie Tucker and Krin Gabbard. It seems fairly clear that there is some sort of relationship between the scripts of Syncopation and another origin story, New Orleans, which came five years later. There are some pretty clear cut parallels in their storytelling, the way they start in New Orleans, and then you follow the musicians to Chicago, they eventually go to New York, and you see a little bit of the evolution of jazz style over the course of that time too. It is the nature of historical films to greatly compress time, and this is something that always happens in jazz movies also. You have characters who don’t seem to have aged a day, yet it seems that 25 or 30 years have gone by in terms of the evolution of the music itself.

The 1938 film Alexander’s Ragtime Band got that started, and it was actually Irving Berlin’s own idea. That movie is stocked with Irving Berlin tunes, and it imagines Alexander – the musician with the ragtime band, and played by Tyrone Power – as if he were a real person who has an inexhaustible thirst for Irving Berlin material, although Berlin’s name never comes up in dialogue in the film. As early as the mid-1920s, Berlin had an idea for a silent film where they would use his own compositions over the years to show the evolution of popular music, and in Alexander’s Ragtime Band, the film starts with that ragtime tune, and towards the end of the film you get into some Fred Astaire-like swing time material. The film ends with a Carnegie Hall concert, not unlike Benny Goodman’s in 1938. In fact, they started filming just after Goodman had played Carnegie Hall.

You also see that big concert ending in Champagne Waltz from the previous year: the classic jazz film ending where musical and personal problems get resolved by a big performance that somehow brings characters at odds together. Another classic example of this is a huge symphonic performance of “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans,” at the end of the film New Orleans, where the opera singer is accompanied on stage by a symphony orchestra, three pianos, a choir, and the entire Woody Herman band.

JJM And Armstrong and Billie Holiday are nowhere to be seen at the end of the movie…

KW Right, they are long gone by then. The same thing happens in Syncopation, the Black characters disappear by the time it’s over, and the white characters come to center stage for the finish.

JJM There’s a wonderful courtroom trial scene in Syncopation…

KW Yes, a socialite played by Bonita Granville has been arrested for playing at a rent party that gets out of hand, and while on trial her lawyer has a piano brought into the courthouse so she can play the boogie-woogie that got her into trouble in the first place, and as soon as the judge and jury start tapping their feet you know how the verdict is going to go.

JJM You wrote that the film New Orleans “features one of the great jazz-movie scenes” that takes place in a kitchen storeroom space at Nick’s Orpheum Casino, a “province of waiters, porters and upstairs maids.” The scene stars Armstrong playing cornet and an elder white “European music master”…

Prof. Ferber (Richard Hageman) and Satchmo (Louis Armstrong) jam in the 1947 film New Orleans

KW Yes, Professor Ferber is this elder European pianist and conductor who hears Armstrong playing, enters the scene, and they proceed to have this dialogue where he praises Armstrong for, the professor says, inventing a secret scale just made for this kind of music. It is a beautiful moment – this European-trained musicologist hears what’s going on and truly appreciates it, and can articulate it. Such discussions about musical specifics or challenges are rare in jazz films. But in The Glenn Miller Story there is a whole sequence about how Miller voiced clarinet over saxophones to achieve the unique sound of his band.

JJM I was struck by how relaxed Armstrong appeared in that scene…

KW Armstrong’s character clearly feels at home playing with Professor Ferber, as soon as he sits down at the piano and touches the keys. The old guy has obviously been paying attention to what’s been going on down there in the back room of the Orpheum Casino. Louis Armstrong was such a natural actor and was really good on screen. I suspect, although I don’t really know for certain, that he didn’t need a whole lot of direction on camera.

JJM Was New Orleans successful in telling the origin story of jazz?

KW It gets some of it right at least. The main contribution that the film made is that it helped to inspire the Armstrong All Stars, because he was working in a more New Orleans style format for the film as opposed to the big band he had been leading for well over a decade. Armstrong’s manager Joe Glaser subsequently set him up with a small band to play a couple of gigs to help promote the film, and he discovered that he really liked playing with a small group. So the birth of Armstrong’s All Stars was an unintended consequence of New Orleans.

.

A video interlude…Watch a clip from the 1941 film Blues in the Night, in which an uninvited white trumpeter (Jack Carson as Leo Powell) jams with the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra

.

JJM You call your chapter devoted to the World War II era “Bands of Brothers.” Tell us a little about the films from this period?

KW I divide the 1940’s into two chapters. One of those is the origin stories we have been talking about, where I also include the movie Rhapsody in Blue and a discussion about how in that film jazz influences sort of magically come to Gershwin without having any direct contact with African Americans.

In the 1940’s there are also many films in which there is some parallel between jazz bands and the military. You see it in Blues in the Night, where there is an ethnically mixed band – much like a platoon in a Warner Bros. war movie – who learn to pull together for the greater good. Robert Rossen – who was accused of being a Communist years later – was the film’s screenwriter and there are some “subversive” ideas in there about how everyone pulls together for the collective. You also see it in Orchestra Wives, where wives who travel with a band basically function as saboteurs, and where Glenn Miller plays Gene Morrison, a fictionalized version of himself. Many of the wives traveling with the band on the train are up to mischief that causes the band to break up, but they eventually get back together when the newest of the wives – played by Ann Rutherford –engineers a reunion.

The literal “bands of brothers,” The Fabulous Dorseys, is the film from 1947 where the battling brothers, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, play themselves and manage to be in the same room together just enough to actually get the movie made. There was a great degree of antagonism between them. Also, there is the Benny Goodman vehicle, Sweet and Low-Down from 1944, in which Benny has to put up with a mutiny when his musicians decide to follow his young and not-yet-ready-for-leadership trombone player – apparently when Benny is on hiatus – and they discover that you can’t have just any schmo running a top band, so, stick with a winner like Benny.

So, in this era you’ve got sabotage, you’ve got mutiny, you’ve got the bands of brothers, and there are also the Seven Dwarfs retellings, the Howard Hawks films Ball of Fire and its remake A Song is Born. Ball of Fire is about a group of lexicographers while A Song is Born is about musicologists, so it has a more direct jazz connection. Danny Kaye is a musicologist who suddenly realizes that jazz exists, so he has to go out in the world and find out what it’s about, and brings some musicians back to help educate him, including Armstrong, Louie Bellson and Lionel Hampton. Benny Goodman appears as one of the jazz professors in a comic role, in which he does an okay job as an old music master who suddenly discovers he has a gift for improvised music.

JJM Reading your book is a reminder about the influence of John Cassavetes on independent film, including on jazz films of the 1960’s…

KW It’s funny. First of all, Cassavetes wasn’t really a jazz guy, but for a minute he was Hollywood’s jazz person. His breakthrough film was Shadows. The original draft had some improvisation in it, and the version of it that was eventually released had less of it, but he had a reputation as a director who was at home with improvisation on the set, maybe a little more than he actually deserved.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands from the television program Johnny Staccato; October, 1959

He sort of backed into this role as a jazz guy, partly because Shadows has a jazz score by Charles Mingus and Shafi Hadi, but also because he went into debt making the film, and his way out of debt was to do a TV series, Johnny Staccato, in which he played a Greenwich Village piano player who winds up solving crimes for people who wander into this basement nightclub. There are, of course, many basement night clubs in jazz narratives. He did that show for about 25 episodes, until he got out of debt, and then he picked a fight with the studio so he could get out of his contract. But because of this jazz association, when he submitted a few scripts to Paramount to make his next film, they chose a jazz story, Too Late Blues, which is about a piano player who writes music but can’t get any night club gigs – he basically plays in the park for the trees. The film is a bit of a metaphor for Cassevetes’ own career at that time because it is about a guy who wants to make his own music, he alienates a lot of people he works with – the way Cassavettes did on Shadows – and he decides to sell out for a while the way Cassavettes did making Johnny Staccato. Then at the end he tries to get back to the ideals he had at the beginning of the film, the way Cassavetes does in the 1960’s, when he becomes a hardcore independent filmmaker.

The technique of Shadows was very influential. It showed people how cheaply you could make a film, that if you were fast and you had a guy watching the corner you didn’t need police permission to shoot on the street, you could just film the scene in two minutes and then jump in a car and run away. He shot in black-and-white with many scenes filmed on the street with pedestrians as unwitting extras. Some scenes would run for quite a long time, something he would be known for later but was already doing in Too Late Blues. And you can see how this aesthetic permeates or at least influences other black-and-white jazz films that come out in the same period, including Shirley Clarke’s The Connection, which was based on the long running stage play with improvised dialogue and music on stage. The story is about eight junkies waiting for their connection to show up, and four of them are jazz musicians, including Freddie Redd, and Jackie McLean in Freddie’s band.

.

A video interlude…Watch a teaser clip of Shirley Clarke’s 1961 film The Connection, a movie influenced by John Cassavettes’ Shadows

.

JJM The cover of your book is a shot from The Connection…

KW Yes, it is a fantastic shot of a silhouette on the wall of a film director and a camera behind the musicians as they are playing.

JJM So Cassavetes’ impact was significant…

KW Yes. You see more of these independent, black-and-white films produced in the 1960’s like A Man Called Adam with Sammy Davis, Jr., who plays a mercurial Miles Davis-like trumpet player capable of great tenderness but also of being a complete boor. One of the odd things about the film is that his girlfriend is played by Cicely Tyson before she actually became involved with Miles Davis. The year after that came the film Sweet Love, Bitter with Dick Gregory playing a Charlie Parker-like saxophonist. Instead of “Bird” he is Richie “Eagle” Stokes, and he resembles Charlie Parker in more ways than you would need just for the purposes of the film’s plot, but you also see a lot of the same post-Cassavetes tactics – the street shooting, the underexposed film shot in black-and-white, and shooting on the fly in public.

Trumpeter Adam Johnson (Sammy Davis Jr.) is arrested for defying racist cops in the 1966 film A Man Called Adam

It’s interesting that in a lot of these decades there is some kind of common theme that emerges, which certainly made it easier to group films into chapters. In the 1970’s there were these high and low budget spectacles – on the one hand there were the big budget movies like New York, New York and Lady Sings the Blues, and then the very cheaply made films like the magnificent Sun Ra vehicle Space is the Place, and the cheapo TV movie biopics of Louis Armstrong and Scott Joplin were made in the same period.

JJM With some of the same people, like Billy Dee Williams, who plays Joplin in Scott Joplin, and of course Billie Holiday’s husband in Lady Sings the Blues…

KW Yes, he was the saintly husband, very unlike any man Billie Holiday ever had in real life, and then he returns in a third jazz film, a little-known Canadian movie from the early 1990’s called Giant Steps, in which he plays a Monk-like piano player who befriends and mentors a young high school trumpet player. That’s the film in which Williams looks like he is having the most fun, miming playing avant-garde piano, and talking in this slow, bear-like voice, like a sit-com Thelonious Monk.

Returning to the 1970’s for a moment, this was the time when these young, brash directors like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola came along, and Hollywood was willing to take chances and let them do the things that in another decade somebody would have said, “You want to spend a ton of money on a film like New York, New York, and the main characters don’t even get together at the end?” That would have been impossible ten years later or ten years earlier.

.

A video interlude…A scene from ‘Round Midnight, Bertrand Tavernier’s 1986 film starring Dexter Gordon

.

JJM You call the chapter focusing on the era of the mid-to-late 1980’s “Suffering Artists.”

KW Yes, although I discuss one of the films from the 1980’s, The Cotton Club, in my chapter for the 1970’s because it seems that film has much more in common with those big spectacle films of that time.

Regarding the “Suffering Artists,” there are a few, Charlie Parker as portrayed in Bird and Dale Turner, played by Dexter Gordon in ‘Round Midnight, being the most obvious. Warner Bros., who distributed the film, was a little reluctant at first because Dexter wasn’t a film star, and they thought that maybe they should get a movie actor to play the lead. It was really Clint Eastwood, who had a very good relationship with the studio, who nudged them to take a chance on the film. It became clear a couple of years later that part of the reason he did is because he had a jazz movie of his own in mind – he had his eye on the script for Bird for quite a while before he was actually able to make it.

JJM Dexter’s performance in the film led to his nomination for a Best Actor Oscar, which remains a moment jazz fans continue to marvel over. Has any other jazz musician ever come close to Dexter’s performance in terms of an actual jazz musician portraying a jazz musician on film?

KW Well, Armstrong has a good character role in A Man Called Adam, if not as intense as Dexter’s in ‘Round Midnight. There are a few jazz musicians who also did some acting. Gerry Mulligan acted in some, including a non-jazz film Bells Are Ringing with his girlfriend Judy Holliday.

JJM Gene Krupa was so charismatic in his roles…

KW Yes, you can slide him into a movie for five minutes and be glad he was there. Ball of Fire, for example, has a great scene at the beginning where, as an encore, he plays a drum solo on a match box with a pair of wooden matches. This scene actually had a lasting effect on the Amsterdam drummer Alan Purves, who has often played in very low volume settings, partly inspired by seeing that film when he was a kid. Krupa also does a little bit of acting as himself every once in a while, and he kind of plays himself as a big kid. But one of the weird things about jazz movies is that musicians playing themselves are always so much older than at the phase of life they are portraying – like Armstrong in his 40s playing the Armstrong of 1917. There is a weird kind of disconnect there.

Another example I wanted to mention of “jazz musicians portraying jazz musicians” is the English People Band, an improvising band who portray the Krakow Jazz Ensemble in Stormy Monday, where they are free improvising but they are also playing the role of another band in a certain way. It is a curious example, and a film that probably doesn’t make a lot of lists of jazz films.

.

A video interlude…A scene from Clint Eastwood’s 1988 film Bird, starring Forest Whitaker as Charlie Parker.

.

JJM When people think about jazz films, Bird seems to remain top of mind. People were critical of it at the time of its release for the way it portrayed Charlie Parker. How has that film held up over the years?

KW I have a lot of the same problems with it now that I had when I first saw it. It is very gloomy. A couple of people who knew Charlie Parker told me they really hated that film because you got no sense of how much fun he was to be around. You can see Forest Whitaker try to be comic sometimes, but there is a pretty heavy air of doom that hovers over his character through the entire film. Another complaint I have is that you don’t get a sense of how bebop arose as a whole bunch of people working together to develop a new language. Parker is portrayed as an isolated figure, even from Dizzy Gillespie, his nominal best friend in the film. You can hear it on the soundtrack also; they had taken Parker solos and stripped them from their backing tracks and then put new glossy backing behind his older recordings. So there was this odd disconnect between the quality of sound of the backing band and Parker himself, as if he were this ghostly presence coming at you from somewhere in the distant past.

One way Bird is really influential in a positive way is that it initiated the tradition of the scrambled-chronology jazz biopic. The film starts out as if it has a flashback structure and you gradually realize that these scenes are not really flashbacks anymore because you are sort of drifting out of one character’s flashback into another character’s flashback in a way that doesn’t make any psychological sense at all, which is okay, you are telling the story and get to take chances. Bebop is about chances, and that’s all right. You see that method of storytelling come back again as early as 1991 in Bix, the Italian movie by Pupi Avati, where some of the story is told in chronological order and some of it is told out of it.

The way of these films is that they are generally less chronological in the beginning and then they gradually fall into a chronological sequence in the middle, and then maybe they pop out of it a little again at the end. You see this later in some biopics that come out in 2016. In Miles Ahead with Don Cheadle as Miles Davis, in Born to Be Blue with Ethan Hawke as Chet Baker, and even a little bit in Nina in which Zoe Saldana plays Nina Simone, you see this scrambled chronology technique. When he was making a biopic in the 1940’s, the great comedy director Preston Sturges pointed out that filmmakers should be truthful about things that actually happened, but they can still shape the arc of the story by chronologically rearranging events, and that is pretty much what happens in some of these jazz films.

JJM I’m really struck by the sheer number of films made about jazz since the 1980’s. In addition to Bird, there was Kansas City, Mo’ Better Blues, Swing Kids, Woody Allen’s Sweet and Lowdown, and more recently Whiplash, Lowdown, La La Land, Bolden, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, the Chet Baker and Miles Davis films you just mentioned, and there is a Billie Holiday film on the immediate horizon. Why are so many jazz films being produced?

KW I don’t know why we are seeing this revival of jazz films at this time. If any of them are wildly successful the way that The Glenn Miller Story was, then we could understand it. Hollywood always chases a trend, but Miles Ahead was not particularly well received, although I think it is a better movie than a lot of jazz people give it credit for. The Chet Baker film wasn’t a huge money maker, and the Nina Simone film was certainly not a success, partly because of the controversy over the casting of Zoe Saldana as Nina Simone. Bolden was in the works for about 12 years before Daniel Pritzker was able to get it finished. So, I am not sure why.

One factor may be that it’s a good challenge for actors. Playing a jazz musician is to play someone who is demonstrative in their actions, and whose lives and careers are very complex. And seeing good actors like Forest Whitaker, Don Cheadle, Ethan Hawke or Zoe Saldana taking on their roles may help explain why someone like Idris Elba would indicate an interest in playing Thelonious Monk. I don’t know if he has spoken about that in the last couple of years, but that’s a movie that I would still very much like to see. There are so many good biopics waiting to happen.

JJM While reading the book the acts of “ghosting” and “sidelining” come up quite a bit..

KW Yes, ghosting is when a musician supplies the music on a soundtrack, ostensibly played by an actor on screen, and the act of miming to that solo that is being ghosted is known as sidelining.

JJM You wrote that the trombone is a relatively easy instrument for actors who are not musicians to mime on screen…

KW Yes, it’s a good instrument to fake on, but some actors worked pretty hard at it. There are some four-trombone scenes in The Glenn Miller Story where Jimmy Stewart is right there with the slide positions. It’s a job for an actor, you just memorize certain moves and stick to them. When they were making The Five Pennies, there is a scene where Armstrong and Red Nichols, played by Danny Kaye, are sidelining to prerecorded solos by Armstrong and the real Red Nichols, and Armstrong kept screwing up his own fingering but Danny Kaye kept getting it right because he was really meticulous about that kind of thing…

.

A video interlude…Watch the trailer for Martin Scorsese’s 1977 film New York, New York

.

JJM Who were some of the musicians known for ghosting or sidelining?

KW John Williams, the jazz pianist who later became Steven Spielberg’s composer, did a lot of sidelining work in the 1950’s. I see him on the bandstand, playing piano in Johnny Staccato episodes. The trumpet player Pete Candoli did a bit of ghosting, and Uan Rasey was a trumpeter who is all over the Chinatown soundtrack – which is what he may be best known for – but he also ghosts the trumpet player in Too Late Blues.

JJM Georgie Auld was known for this work…

KW He was a big part of New York, New York. He supplied DeNiro’s tenor saxophone sound and actually plays the bandleader who DeNiro and Liza Minnelli go out on the road with right after World War II. Auld was this cocky guy with an attitude, and his personality left its mark on the way DeNiro played the character of Jimmy Doyle in that film.

Ghosting is an interesting art because the sound that a musician makes on an instrument should reveal something about the actor’s character. Richard Gere in The Cotton Club is an interesting example of this. He was a talented trumpet player when he was a teenager, and he wanted to play his own cornet parts in the film, even though the Cotton Club didn’t hire white musicians. Gere played his own solos on the soundtrack but the cornetist Warren Vache actually wrote them out and taught him how to play them, solos that wouldn’t strain his non-professional chops too badly but still gave a sense of zesty period syncopations. But you don’t really get a sense of him playing the way he feels.

By contrast, in the film All the Fine Young Cannibals, Robert Wagner plays this vaguely Chet Baker-like trumpet player from North Texas who plays his feelings on his horn. He goes down to a Black club down in Deep Ellum where he has been playing since he was a little kid and plays out his emotions, having missed his preacher father’s funeral earlier in the day. It’s completely over the top, but it’s funny storytelling because it makes this completely direct connection between what you play and what you feel. My book is called Play the Way You Feel for a reason – because this advice is being dispensed in jazz films all along. It came up in so many films that I thought it was a good title.

JJM Readers of this interview may know many of the movies we have been talking about…

KW Right, but there are a lot of films in the book that people generally don’t know. That was part of my intent, to expose films that many people hadn’t heard about.

JJM What are five of your favorite jazz films you’d like to recommend?

KW New York, New York is a really nice piece of work that is thematically coherent. It’s very long, and there is a lot of Liza Minnelli in it, but it is a really good film.

Paris Blues with Sidney Poitier and Paul Newman as expatriate musicians in Paris in the early 1960’s is a nice film, and there is fantastic music by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn in it, as well as some interesting discussion of the education of a jazz composer who is trying to grapple with European influence versus jazz in his own career.

Syncopation is an overlooked origin story and a really enjoyable film from the early 1940’s, with nice performances by Bonita Granville, Jackie Cooper and Adolphe Menjou, and a jam sequence at the end that includes Gene Krupa, Benny Goodman, Charlie Barnet, Harry James and Joe Venuti.

Space is the Place starring Sun Ra, jazz film’s only supergalactic hero. In my opinion, the one hour version that Sun Ra cuts all the sexy stuff out of is much better than the hour and twenty minute restored version, but I would recommend seeing either version.

Finally, a very good comedy is Second Chorus with Fred Astaire and Artie Shaw, a film about a couple of trumpet players, played by Astaire and Burgess Meredith, who are trying to land a job with Artie Shaw so they can sweet talk his manager Paulette Goddard. Astaire later either defended the film or knocked it depending on what kind of mood he was in. These are films I particularly enjoy.

JJM Your book spans 93 years of film history…

KW I learned a lot about Hollywood and filmmaking during this project. As I mentioned at the outset of our conversation, my friend Chuck Stephens – who is such a knowledgeable jazz critic and historian – advised me on this project, so I wanted to be sure I didn’t do anything to embarrass either of us. I probably read or read around in about 250 books on jazz or film while doing research for this, and on the filmmaking side, there was a lot to sift through. On the jazz side, biographers of musicians are generally uninterested in the films they made, which often don’t rate any mention at all – or it’s just details of the plot. In fairness, many of these biographies were written before these films were easier to come across.

JJM The internet is a great companion to your book. I found myself reading a segment of it and then I’d seek out a film clip or an entire film of interest, many of which are available on YouTube…

KW I set out to write a book that you could either read straight through as a history or just skip around and read the different entries, most of which include a full plot synopsis, a list of the actors, directors, and new songs. But I also wanted to have a book that would invite people to browse around, especially in this environment we have now where, as you say, you can go to YouTube or streaming services like Netflix and view complete films that are in the book. It has never been so easy to see so many of these films as it is now.

.

___

.

“Movies that tell jazz stories cut across diverse genres: biopic, romance, musical, comedy, and science fiction; horror, crime, and comeback stories; “race movies” and modernized Shakespeare. But they also make up a genre of their own, with narrative and stylistic conventions that rise up, recede, and maybe return, even as new ones arise to replace them. It was time someone tried to survey them all – even knowing down deep there’s always one more out there.”

-Kevin Whitehead

.

.

Play the Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film

by Kevin Whitehead

.

.

Kevin Whitehead, the longtime jazz critic for NPR’s “Fresh Air,” has

written about jazz, movies and popular culture for 40 years. His books

include New Dutch Swing (1998), and Why Jazz? A Concise Guide (2011). His essays have appeared in such collections as Discover Jazz,

The Cartoon Music Book and Traveling the Spaceways: Sun Ra, the

Astro-Black and Other Solar Myths. Whitehead has taught at the

University of Kansas, Towson University, and Goucher College.

.

.

___

.

.

“What makes all of this quite enjoyable is the colorful way that [Whitehead] writes, his wit, and a countless number of fascinating details… Even the most devoted jazz film experts will learn a great deal from this book.”

-Scott Yanow, L.A. Jazz Scene

.

“Jazz and cinema, the two definitive art forms of the 20th Century, have led an often troubled co-existence. Play the Way You Feel traces the frequent missteps and occasional triumphs of jazz in film with the deep knowledge, superior taste, and acerbic wit we have come to expect from Kevin Whitehead. ÂAn essential book for all jazz fans, and a necessary corrective for anyone whose knowledge of the music is based on what they have learned at the movies.”

– Bob Blumenthal, author of Jazz: An Introduction to the History and Legends Behind America’s Music

.

“Readers… will be rewarded by insights from an author of discerning taste with a deep understanding of his subject, who yields fresh perspectives on even well-known films.”

– Library Journal

..

.

Read an excerpt from the book by clicking here

.

.

Kevin Whitehead’s book features extensive reviews and commentary on over 100 films, some of which were discussed during this interview.

He put together an extensive YouTube playlist that serves as an excellent companion to the book. He calls the playlist – which features 136 videos – “Play the Way You Feel: Movies Telling Jazz Stories,” and it can be accessed by clicking here, or on the link below.

Play the Way You Feel: Movies Telling Jazz Stories

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on December 14, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

Unless noted otherwise, the photographs within the interview are from the book, Play the Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film

.

.

.