.

.

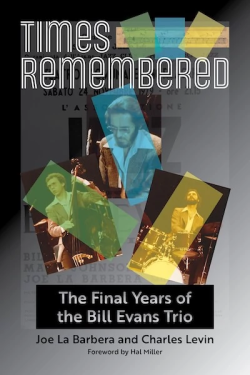

photo by Roberto Cifarelli

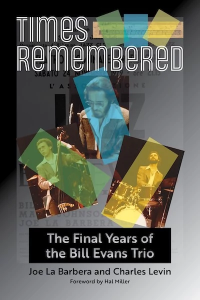

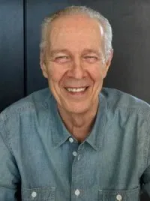

Joe La Barbera, co-author (with Charles Levin) of Times Remembered: The Final Years of the Bill Evans Trio (University of North Texas Press)

.

.

___

.

.

…..Much has been written about Bill Evans since his death in September of 1980; his enormous contributions to jazz have been well documented in two previous books, Peter Pettinger’s How My Heart Sings and Keith Shadwick’s Everything Happens to Me. For all of their scholarly excellence, the key pieces those books were missing have now been added by this more personal, insider look at Evans the man and artist by Joe La Barbera, Evans’ drummer during the last twenty months of his life. That last Evans trio, also including bassist Marc Johnson, seemed to represent a revitalization of Evans’ artistry and was in a sense a final flowering of his genius.

…..The book has been praised by some of today’s most outstanding jazz musicians. Pianist Renee Rosnes has called it, “an insightful, intimate look into the mind, music and travels of Bill Evans and his trio during his turbulent, final years…Many gems are revealed.” Pianist and organist Larry Goldings has said, “Joe’s honest and loving portrait of Bill Evans should be read by anyone interested in the colorful and often complicated world of creative artists.”

…..Joe La Barbera is one of jazz’s finest drummers; his career was well established when he first joined Evans, and he has continued to be an in-demand drummer for some of the world’s premier jazz artists. Joe is a highly musical drummer, perfectly suited to the lyrical, ‘singing’ style of Evans’ concept. Drummer Peter Erskine has described Joe’s musical attributes: “Joe La Barbera is a master of balance. I’m not talking about dynamics so much as that intuitive sense and ability to control the push and pull necessary to bring a piece of music alive.”

…..In a February 24, 2022 interview, La Barbera and Jerry Jazz Musician contributing writer Bob Hecht talked about the book, and the significance of Evans’ last trio.

.

___

.

photo by Brian McMillen

Bill Evans, 1980

.

“Over forty years have elapsed since Bill Evans’ death. Since that time a day hasn’t passed without his memory evoked in some way in my life. Whether through music, family life or even exercise (unbelievable!), I am reminded of him in different ways. I realize that Bill Evans and exercise don’t automatically equate to most jazz fans’ minds, but he was in fact a very athletic youth, who played par golf, was a scratch bowler and a pool shark!

“Most often, he comes to mind with music. The many lesson I learned from him have stayed with me and shaped my musical life in a significant way. Just being on stage with him had a transforming effect. He was completely committed to the music, immersed from the minute we started to perform. The music grew from song to song in an organic and dynamic way each night but always guided by a clear vision of a complete and satisfying program.”

-Joe La Barbera

.

Listen to the Bill Evans Trio (with Joe La Barbera on drums and Marc Johnson on bass) play “Autumn Leaves,” from Turn Out The Stars : The Final Village Vanguard Recordings/June 1980

.

.

BH Well, first of all let me say ‘Happy Birthday’ Joe—I understand you had a birthday this week…

JLB I did, I turned 74 on Tuesday.

BH Congratulations. And from reading your book I now more fully appreciate what that means—because at 74, you are just one year short of a 70-year-long career as a professional musician, having started playing paying gigs at the age of five, with the La Barbera Family Band. Not too many people can say such a thing.

JLB Yeah, it’s true, I did, I started playing gigs with the family band at five years old.

BH That must have been a very rich experience.

JLB It was, and I wasn’t even aware of what I was getting at the time. You know, first of all, to be in a family that loving was extraordinary. We did everything together as a family—scouting, music, vacations, we were in it together, and the extended family was fabulous as well. In terms of music, what I was getting was a broad exposure to not only the rich history of my father’s Sicilian roots with all of the music from that world, but we were playing stock arrangements of Fletcher Henderson and Glenn Miller and pop tunes of the day. I was learning standard tunes starting at five years old.

BH What a foundation. I knew that when you joined Bill Evans in 1979, you were already a journeyman jazz musician, but I hadn’t been familiar with your playing back then. So, it was very impressive to read that when you started with Bill you already had a 25-year career under your belt, with great depth of experience playing with some heavy cats, including John Scofield, Chuck Mangione, Gary Burton, Toots Thielemans, Woody Herman Jim Hall, Art Farmer, it’s like a who’s who of greats. And you had also been keenly aware of Bill’s music from the time you were 12 or 13 years old, too.

JLB That’s right.

BH So then, in late 1978, you got an audition opportunity with Bill, and soon learned you had gotten the gig. However, it was interesting to me to read that you had actually had an opportunity to audition for him several years earlier, but had passed on it because it didn’t feel like it was the right time for you.

JLB It wasn’t, as I say in the book; you know, I had a close relationship with Chuck Mangione, and his band was starting to get some traction in the biz—we had either just recorded or were going to record two albums for A&M. And I really felt like it was it was time for Chuck, I didn’t really feel like it was time for me to leave Chuck’s band.

BH But then the time did come a few years later. The audition story is fascinating, because you were asked to come and play a live set with Bill at the Vanguard—that’s how he was auditioning drummers that week at the Vanguard—and you were on a gig a few blocks away with Toots Thielemans…

JLB That’s correct. And actually, it was Toots, who was nice enough to schedule his sets so that I could run over there on the break and play a set with Bill and then run back and play his gig.

BH So you were warmed up for sure…

JLB (Laughs) Yes, I was ready.

BH And what was that experience like? How did you feel walking down those steps in the Vanguard, walking up to the bandstand and there’s Bill Evans?

JLB I was excited, obviously, Bob, but the fact is what you said previously about me having a 25-year career prior to this, it’s so true, man. I had played with a lot of people, I’d had a lot of significant road time, so I didn’t feel nervous. I just felt excited because he was such a hero. And it was a whirlwind, I ran across 12th street, down the steps of the Vanguard, onto the stage, said hello to Bill and Marc, made a couple of adjustments to the drums, and we hit it. And that’s the way it was going forward, too. No discussion. Bill would just start playing and it was up to us to get on board.

BH So even that very first time, you didn’t know what he was going to start playing…

JLB No, but as I describe in the book, I was familiar with his sound and with his approach. So even though maybe I didn’t know the particular song he was playing, it was not that much of a mystery because I was familiar with how he played.

Marc Johnson; Rome, c. 1980

BH And how did it feel with you and Marc right off the bat?

JLB It was great. His time was so great. Here’s the thing—Marc and I shared that similar experience of having played with Woody Herman’s band. And in the jazz world, I think most musicians would agree, if you’ve played with Woody’s band, it is your entrée into jazz because people were confident that if you could cut his book and make him happy, then you could probably do what they needed as well. Marc and I had that thing together, right from the start.

BH So then you play the audition set. And as you go to leave, I think Bill said something to you, right?

JLB Yeah. He said, ‘Hey, man, you’ve been checking out my book, you seem to know everything.’ I didn’t say it to him, but I could have said, ‘Well, I’ve listened to you since I was a kid!’

BH So then you finish that audition, you go back across the street and play a set with Toots…

JLB Right, those times were great for me in New York, Bob, because I had finally made my way into the inner circle of the jazz players. And my life pretty much back then was a week at the Vanguard, a week at Hoppers, a week at Sweet Basil, that’s what I was doing at the time.

BH So you get the job with Bill, and right away the music is really happening. You write this in your book, “We all found ourselves anticipating and reacting to one another’s musical ideas at the right moment.” You write beautifully about the kind of interplay between the musicians and about how you could hear that Bill was responding to what you were doing. I personally feel that this trio was very special, and represented a strong revitalization of Bill’s music. You know, it’s been noted that there were some periods earlier in the 70’s, where he seemed to sometimes be stuck in kind of an artistic rut. But this combination really did re-energize the trio, and brought it up to a new level.

JLB In regards to the trio with Marc and me I would just say that it was the right thing happening at the right time for the three of us. And you cannot predict whether that chemistry will work. You know, every one of his trios had outstanding players.

BH He didn’t hire any anybody who wasn’t at the highest level.

JLB And he certainly wouldn’t keep anybody if he didn’t love the way that person played. It was just the way things happened with this trio, it was just the right combination of personalities and experiences. And maybe it was at the right time in Bill’s life, when he wanted to make new discoveries. I really can’t say, but it just started to happen immediately with that first gig in Philadelphia opposite Art Blakey. We just clicked.

The 1979 album We Will Meet Again [Warner Bros.]

BH So then your first time out with Bill on record was the wonderful We Will Meet Again album with horns—I always love the way Bill played with horns, he really got more assertive and stronger in his comping—and that’s a great album with Larry Schneider on saxes and Tom Harrell on trumpet and flugelhorn. Were you pleased with that record and that experience?

JLB Absolutely. It was thrilling to be with recording with Bill in Columbia’s famous 30th Street studio.

BH The same studio where a lot of historic things had happened…

JLB Oh my God, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Miles Davis—Kind of Blue was recorded there. As I say in the book, Tom and Larry wanted to know exactly where Trane and Miles had stood during that Kind of Blue session, and so Bill showed them and bam, that’s where they chose to stand during our session too. And I agree with you, I always enjoyed hearing Bill comp behind horns, because he was so good at it.

BH And that record won two Grammy awards.

JLB It did indeed, for Best Performance by a Jazz Group and Best Jazz Solo Performance.

BH Right away on that record, for instance with your soloing on “Peri’s Scope,” you were asserting yourself as a very dynamic and swinging drummer for Bill. You and Marc were quite a bit younger than Bill, you by some 20 years and Marc nearly 30 years. How do you think the age differences factored in your relationships either musically or interpersonally?

JLB Well, in terms of the relationship musically, not a bit, we were relating as equals. But on a personal level, because I was older than Marc—and had been around the block a few times—I think Bill and I had more of a fraternal relationship. He always looked at Marc, who was only 24 at the start, like a son. He was so protective of Marc. He loved Marc. He saw in Marc that same spirit as a Scott LaFaro. You know, that same purity and that same energy and that same high level of musicianship, but I think it was more of a fraternal thing with me.

The Paris Concert (Edition One) [Elektra/Musician, 1979]

The Paris Concert (Edition Two) [Elektra/Musician, 1979]

BH Another landmark recording for the trio came in November of ’79, the two-volume Paris Concert, which wasn’t released until several years after his death. What a beautiful, transcendent concert.

JLB It was a special, special evening. I mean, first and foremost—and this is a point that I drive home repeatedly in the book—he had an instrument that was worthy of him. And whenever that happened, Bill was going to give you the performance of a lifetime. And he loved that piano. He loved it so much that after the concert he played some more for himself and the people just talking and milling about backstage. With his coat on, ready to go back to his hotel room, he stayed and played a while longer.

BH What a great image. The music in that concert has many impressionistic elements, and the French audience clearly appreciated the entire thing.

JLB They are consummate music lovers and jazz fans, and the audience was there for Bill.

BH That Paris concert included a remarkable version of “Nardis,” which Bill referred to as the trio’s “therapy” tune, and which featured a lot of solo room for everyone. It was an intense, emotional exploration.

JLB It’s testimony to Bill’s communication skills that he could take an audience that might have been there for a “Waltz for Debby” or, you know, a “How My Heart Sings” and then finally have them so firmly in your grasp that you could drop something like that on them at the end of the night. They were rapt, they could not, would not budge. They wanted everything. And it was an explosion by the end of it.

BH I read a comment of Bill’s in which he said he wished he could string together all of Marc’s solos on “Nardis,” because he thought they were so remarkable.

JLB As Marc soloed, night after night, Bill would start out listening and the smile would just grow on his face. And he would nod and he would just follow Marc every step of the way.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1979 recording of Bill Evans playing “Letter to Evan”

.

BH You have cited Bill’s composition, “Letter to Evan,” dedicated to his son, as being one of his most personal pieces, which he played solo there in Paris. And I’ve listened to that since I first got those records when they came out, and over the years, it’s just grown and grown on me. For me, it wasn’t an obvious candidate for one of his strongest melodies, but the more I hear it, the deeper it gets. It’s a very moving piece.

JLB It’s like he’s telling a story. If you’re listening to it for a melody, then maybe you might not be impressed with it. But if you listen to it for its intent—which is that he knows full well he’s not going to live to see Evan grow up—and he’s telling him as much, offering whatever advice he can pass through music, the song takes on added meaning.

BH And Evan got something by osmosis, if not by time spent with Bill—he got a successful film-scoring career.

JLB I think it’s genetics. Evan is a sharp young man. He really is, he’s got a successful career and he’s his own man. He’s not someone trading on his father’s name. He’s created his own path in life, and one of my big regrets is that Bill did not live to see that, because he would have been extremely proud of him.

BH You spent Bill’s last twenty months as his drummer, and that was now over 40 years ago. What prompted you to do the book?

Joe La Barbera at the Festival Internacional De Jazz De Punta Del Este Finca El Sosiego, Maldonado, Uruguay; 2015

JLB Oh, I had been working on it alone for probably 10 years. Just collecting stories, because all of these memories were just coming to the front of my brain daily. You know, Bill had such an impact on me that I was referencing him constantly in my own work. But I just wanted to get these stories down on paper, it just seemed like something that I had to do. Once Charles Levin came on board we started to formalize it for publication.

BH Well, the book does give a different, and much more personal view of Bill than previous publications.

JLB In a sense, I felt compelled to get it off my chest—especially the heavy stuff—I just didn’t want to carry that anymore.

BH Well, it’s very powerful the way that you describe the day of his death, right up front in the prologue—that hair-raising story of his final day on the planet.

JLB Bill’s health had deteriorated to a point where it was probably beyond salvation, honestly. But even at that late stage, I was optimistic, maybe overly naïve, but he had finally agreed to go see his doctor. And so, Laurie Verchomin, his girlfriend and I were driving Bill into Manhattan, and we went to the methadone clinic where he had been enrolled since 1974, I believe…

BH Back when he had gotten off heroin…

JLB Unfortunately, he had abused that program so many times that the doctor refused to see him that day. And I understand it, the frustration of it, there are just some people who can’t be saved or don’t want to be saved. I think that was the case. Anyway, at that particular point, Bill became violently ill and we had to make our way over to Mt. Sinai Hospital, which involved going the wrong way on one-way streets. When we finally got there, I helped carry Bill into the emergency room. And, as I wrote, I set him down on an examination table and then we get one last look at each other. And the attendant asked me to leave the room, and that was pretty much it.

BH And how did Bill look to you at that point, was he even aware of what was going on?

JLB I can only assume from the vacant stare in his eyes that he was in incredible shock. Whether or not he was aware of his situation, I really couldn’t say.

BH What a tragic ending for such a creative genius—and tragic that he had to suffer from such a self-destructive syndrome.

photo by Brian McMillen

Bill Evans; August, 1980

JLB I don’t know that he viewed it as suffering, quite frankly. He would never talk about it. He would always just refer to it as a personal problem. He would never name any names. People were always curious as to how he got started with drugs. And he never brought that up. This is something that came into mind this morning, as I was thinking about speaking with you today, Bob. Bill did a radio interview in Chicago in 1979, with Dick Buckley, a very well-known and well-loved personality in Chicago jazz, who asked Bill about the hazards of the road. I believe that he was kind of like opening the door for Bill to go to what we’re talking about.

BH About the hazards of drugs…

JLB Right, being exposed to that, but what Bill shared in this conversation was very telling. What he said was that the life of a traveling musician is so disruptive, violently disruptive, to normal family life. Right then he was experiencing that disruption in his own marriage—at the time he and his wife Nenette were estranged, and there were a lot of issues. At the same time, he was always concerned about my family and me keeping my family together, which I was devoted to. Nothing was going to deter me from that. But what Bill considered to be a hazard of the road was not drugs. It was the damage being away from home so much can do to someone’s family.

BH Very interesting. Of course, another hazard of the road, as you write, is the challenge of having to play inferior pianos.

JLB Well, pianos, yes, that’s an everyday issue, too, but you know often those issues can be dealt with by your manager. But there’s nothing you can do when you choose the life of a jazz musician—there’s nothing that you can do to prevent you from being away from home, because that’s the job.

BH So that has to be really hard on families.

JLB It is. I mean, my marriage to my first wife, lasted 10 years. And that was, you know, until well after Bill had passed; then I started working with Tony Bennett, and again, that was constant travel. We eventually divorced but for a variety of reasons.

BH Bill’s significance as a pianist of course dates back to the late 50’s, when it is generally considered that he revolutionized the role of the piano trio, by essentially creating a more democratic, shared role with bass and drums. He was helped enormously in that by the talents of bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian. After Scott’s early death, Bill had numerous combinations of musicians in his trios, all of them excellent; but I believe, Joe, that that original feeling of energy and musical interplay was more evident in your last version of the trio than any since LaFaro and Motian.

JLB Thank you, Bob. But, you know, when you think about that first trio, the discoveries they made were totally spontaneous. The only thing Bill wanted from Paul and Scott was a commitment to be in a band together. Once he had that, then they were free to just go after certain things, and they all kind of had a vision of something other than the status quo of piano trio—which at that time would have been Ahmad Jamal, Red Garland or Oscar Peterson, but Bill’s trio is something different. And they started to just try things. And that’s how it came about. I think they had such an impact. Bill was at such a loss after Scott was killed, but the discoveries they made became a style, a way for the Bill Evans Trio to sound. And it still worked, and it worked for a long time. But all the trios found their own voice with the music, they were all trying to make changes and find their own identity. For some reason when it got to Marc and me, it just seemed to come full circle. I don’t know how to explain it. But all I can say is that we didn’t have to talk about anything. We didn’t have to discuss one note, you know, we just played and we reacted to each other.

© Veryl Oakland

Bill Evans; 1969

BH Never any rehearsals. No set lists. Just all in the moment, responding in the moment.

JLB Well, that was Bill. That’s the way he operated. And it’s ironic in a way because he was perceived by the press differently, because he had that Ivy League look with the glasses, and short hair so he looked like some professor or some over-zealous student. But the fact is that with Bill it was always all about feeling. Always.

BH And I’m sure that must be why he was able to break through the way he did to a larger audience. Not really a crossover audience per se, but a larger audience within the spectrum of people who appreciate jazz, to a greater extent than most other jazz pianists. And that’s ironic to me because he’s intellectual, he’s quiet—for the most part—he’s nuanced, he uses what could be considered unusual harmonies, and he has a musical presence that requires fairly intense listening. And yet he had millions of devoted listeners.

JLB He communicated. That’s the thing. People reacted to Bill on an emotional level. That’s why he had those fans—he reached out and grabbed them. You were compelled to listen, you had to listen.

BH And then fall in love with the artist. ‘That’s my Bill Evans!’ I’ve met so many people over the decades who had such a personal feeling about the man—they may not have ever exchanged a word with him—and yet he was a major factor in their artistic life.

JLB That is right on the money. I mean, they would actually take ownership of the man and in a very aggressive manner sometimes, and God help you if you said something that maybe they didn’t particularly agree with—they were possessive of their relationship with Bill.

BH In Keith Shadwick’s biography of Bill (Everything Happens To Me), you’re quoted as saying that your ambition for playing with Bill was, in a sense, you aspired to be like a Scott LaFaro insofar as contributing to the trio. Was that an ambition that was achievable?

JLB Absolutely. It had nothing to do with trying to sound like a bass player. What I was hearing with Scott and Bill was communication on a level that was so immediate and I wanted that with Bill. And thanks to Paul Motian, for opening the doors for all the drummers to be able to understand how you can phrase time as opposed to playing time. I had a framework to work with. So, I was able to do that with Marc, while still maintaining some kind of consistency of the time. I think another thing that I liked about Scott LaFaro was that he was fearless. This guy was willing to take chances without always knowing where he was going to land.

BH I read this quote from Bill, about comparing your trio with his first trio. He said, “I don’t compare them qualitatively so much. But characteristically, I think the last trio resembles the first more than any other. The music is evolving and growing of itself, like the first trio.” Joe, that must have felt pretty good to have that be his assessment.

JLB Oh, my God. I mean, right from the start, he was saying nice things about the group. But even more important was that he was excited. He used to say, “I can’t wait to get to work at night.” What more would you want to hear from a giant like that?

BH You also recount the impact of a major tragedy in Bill’s life in the spring of ’79, the death by suicide of his brother Harry. Harry was older, right?

JLB Yes, Harry was his older brother and he actually introduced Bill to jazz, and they were as close as I am with my brothers. They went through music together.

BH I imagine you know that old video that they did together? It’s very interesting. (The Universal Mind Of Bill Evans: The Creative Process And Self-Teaching)

JLB Oh, it’s great, and what’s great about it is that it shows Bill’s belief in the “joy of discovery.” Pat Evans, Harry’s widow, would say that every time they would get together, Harry would be pestering Bill to show him some voicings and Bill would never do it. And that is the thrust of that video. He was right—he doesn’t want to rob the student or the other musician of the joy of discovery, of making those discoveries yourself, because those are the important ones.

BH Following Harry’s death, I believe Marc expressed the feeling that in a sense it represented the beginning of the end for Bill.

JLB I think Marc’s right. Bill was truly devastated.

BH For me, then, the story of that last year just gets sadder; escalating drug use begins to have noticeable effects on his playing and he doesn’t always have sufficient stamina for a full touring schedule, even though he was in demand worldwide.

JLB Physically, he just wasn’t able to go out there and meet the demands, to play as many gigs as were being offered. But once he was on stage anywhere he was full of life.

BH In the book you recount having more than one difficult conversation with him about the toll his drug use and associated health issues were taking…

JLB Yeah, we did, we had a couple of head-to-heads. I really want to stress though, that I purposely downplayed the addiction angle in the book, because I feel like that’s something that people will go to unnecessarily. As he stated, it’s a personal problem. Unfortunately, in our society, we always view this as some kind of a personal choice issue, which maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. We have to be more humane about it, I think.

BH At the same time, he was also facing the consequences of a lot of problems, a lot of health problems. Addiction certainly takes its toll, and his addiction had wreaked havoc with his body. And, you know, the question arises, as other people have asked, too: How much of the intensity of that last period was, on some level, his realizing that this was his final chapter—maybe not knowing how long that chapter was going to be but that he was in a final chapter. There’s a feeling of intensity in the music of that period that to me has always felt like, here’s an artist who’s trying to get everything out, everything that he has left, every last drop of it. And you can feel that and in just about every note.

JLB That’s absolutely true. And at the time, I simply couldn’t see it. I was just experiencing him being excited about the music, and growing again. Bill Evans growing. He was starting to reach and stretch for things, he was composing again. So, it was kind of a rebirth. But you’re absolutely correct. I think his heart and soul told him that the end was coming and he was going to take advantage of every opportunity to play.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1980 performance of Bill Evans playing “Tiffany” [Universal]

.

BH One of his new compositions was in honor of the birth of your daughter. It’s a lovely story of how he played the song, “Tiffany,” for you and your wife.

JLB Yes, he called and played it for us over the phone. I mean, that is something that will stay with us forever and beyond. In this particular period, Bill had started to write again, as I said, and he was excited about it. He would show up to the gig early and say, “Hey guys, check out this tune I’m working on.” And then I would hear him when I would stay with him in the apartment, he’d be playing these motifs over and over again and trying different keys and different ways to phrase it. He took his time with his compositions. He was really an intense guy musically, he took music very seriously, and he would not hurry anything. And then when it was done, it was done, ready to go, and that’s the way it stayed. That was the last time anybody had to think about it.

Bill would often talk about the architecture of music; he would say, “If the architecture isn’t sound, it’s going to fail, the composition is going to fail.” And, if you look at all of his arrangements, there’s a solid architecture to every tune, whether it’s his own or a standard tune. He created an arrangement that worked. Once you learned that arrangement, you were totally cool, then 98% of your energies and abilities could be focused on being creative.

BH Overall, what an exhilarating experience that must have been for you, those 20 months playing with Bill.

JLB Exhilarating, frustrating, painful, joyous, heartbreaking. All of the above.

BH And yet you emphasize, despite his issues, he never seemed less than totally immersed in the music.

JLB That’s absolutely true. He was not going to cut it short. He wasn’t going to do anything less than 100%.

BH And the evidence of that is there, in the form of recorded concerts up to very near the end. Even on his last recordings, at the Vanguard and at Keystone Korner, while he was reportedly in terrible physical condition, he put everything he had into the music.

JLB Somehow he would find that inner strength. He used to say, and it’s in the book as well, “my physical exterior is a complete wreck but my inner spirit is pure.” And the point he was trying to drive home was that there are a lot of people that look like the embodiment of good health but inside they’re maybe not living so pure life, in other words their motivation isn’t as pure as his and I think that that purity is what gave him the strength. Because honest-to-goodness, man, there were nights when he could barely stand up and he would get on that stage and it was as if he was a young man again.

BH During the time you were with him, you also got to hang off the bandstand quite a bit, sometimes staying at his place. Is it possible to describe Bill as a person, his personality?

photo by Steve Schapiro/via Wikimedia Commons

Bill Evans; 1961

.

photo by Seppo Heinonen / Lehtikuva/Wikimedia Commons

Bill Evans in Finland; 1964

JLB He was very normal. One of the reasons that he and I clicked personally was because we had a lot of shared experiences. We were a generation apart, but we both grew up in music, in families with music in the household. We were both Boy Scouts. I outranked him—I was an Eagle Scout. He only made it to Life. But he thought that was impressive. We were both in the military. We were both in the band. We both got to be an E-5, you know, we both basically made sergeant. We had both been on a big band, we had listened to a lot of the same records coming up. So, we had a lot of common ground. But in general, he was just a very normal person. You know, he just happened to be the greatest jazz pianist of the time.

Our conversations would run the gamut. He liked sports. He liked the horse races for sure. You know, that was another dissertation he gave in a radio interview to Dick Buckley in Chicago: Dick asked him, have you got a horse racing system? And I think Dick was expecting a short answer, like, some kind of a mathematical equation. No, Bill Evans studied anything that he was interested in. Horse racing—he didn’t just go to the track and decide that maybe today’s his lucky day. He knew all the jockeys. And these are at particular race tracks, right? He knew the horses, he knew the conditions. He knew how many times the horses had run that week. Wow. All of the above. He knew the field, who the horses were racing against. That’s why he came away a winner. And that’s why he was so great, musically, too, because he knew music. Cold. He knew all of it. And yet, with all that information, there was always room for something new and unexpected to happen, like in a horse race.

BH You quote Bill as saying “talent is cheap.” And I’ve read that famous quote where he talks about how he had to work so hard to master music, because it didn’t come easily and he didn’t have very good ears. And then he said that he felt putting in the work was the talent…

JLB The fact is, he was willing to put the work in, and that was a part of his talent. Obviously, you and I will look at this differently, right? He had gifts, no doubt.

BH I would say genius gifts.

JLB But that was, again, from work—for example, his sight reading was legendary, but things like that he already possessed by the time he graduated from high school. What college did for Bill was to expand on his harmonic knowledge, and he always used to single out Gretchen Magee, who was his theory teacher at Southeastern Louisiana University, for opening some doors. But it was because he was willing to do the hard work—not only with harmony but with rhythm. That rhythmic displacement concept of his—that was worked on hard, and you just can’t say I’m going to do this, right? You have to actually spend time on it. Just like Elvin Jones had to spend some time trying to figure out how he could express the time for Coltrane differently than Jimmy Cobb or whoever else played.

BH So is it possible to say, Joe, what you learned from being with Bill?

JLB Oh, absolutely. Dedication for one thing, right off the bat, you’ve got to be dedicated to this. And you’ve got to be willing to give it your all. And by your all, you decide what your all is—Bill Evans gave his life basically for the music. I’m not willing to do that. And I don’t feel it’s necessary. I learned how to pace an evening’s worth of music. You know, I’ve had a band for 25 years now, the things I learned from Bill include: How do you start a set? How do you vary the songs so the next one doesn’t sound like the previous one? How do you get yourself out of the picture, musically. Bill would sometimes drop out of the trio, and it would just be me and Marc from time to time, to get that sound of the piano away from the listener’s ears. I’ve learned to do that with the drums. I learned to be the confidence for the bandstand. That’s what I do for my band, I am the rock, I’m the foundation, so everybody else can just relax and play; and musicians for years have told me that it’s so easy to play with me. And that’s what I’m trying to do. So those are things I learned from Bill. And also, to keep it open. You know, don’t put any restrictions on music, let people play the way they hear it.

.

___

.

© Veryl Oakland

“In the two years I played with him, he never put his own ego ahead of the music. As a sideman, I was given a great deal of freedom but along with it came responsibility. The music came first – always.”

-Joe La Barbera

.

.

Listen to the 1979 recording of Bill Evans playing “For All We Know (We May Never Meet Again) [Craft Recordings/Concord Music Group]

.

.

Watch the 1980 performance of the Bill Evans Trio (with Joe La Barbera and Marc Johnson) at the Molde Jazz Festival

.

.

___

.

.

Times Remembered: The Final Years of the Bill Evans Trio, by Joe La Barbera and Charles Levin (University of North Texas Press)

Praise for the book:

.

“Times Remembered is the perfect book on jazz to be published at the perfect time. No other book on Evans has the personal, first-person point of view. This is an important, and perhaps essential, contribution to jazz scholarship. Joe La Barbera gives us a candid insight into one of the most important and influential performers in the history of jazz.”

—Bruce Klauber, author of World of Gene Krupa, and writer/producer of Warner Brothers’ DVD series, Jazz Legends

.

“As the drummer with Bill Evans from 1978-1980, author Joe La Barbera recounts stories that take readers into the creative process of the Bill Evans Trio. From tune selection, to musical interaction and time feel, La Barbera finally tells the inside story of the musical genius of Bill Evans. In addition to the rare musical insight, readers get a true sense of Bill Evans the friend, father, band leader, and artist. It wasn’t always happy or easy to read about the end of Evans’s life, but thanks to La Barbera’s great writing the story unfolded with humility, love, and honesty.”

—Chris Smith, author of The View from the Back of the Band: The Life and Music of Mel Lewis

.

“An insightful, intimate look into the mind, music and travels of pianist Bill Evans and his trio during his turbulent final years, as remembered by his colleague and friend Joe La Barbera. Many gems are revealed, from Evans’s reflections on recording Kind of Blue with Miles Davis, to his conceptions on the art of playing trio, to thought provoking words of guidance for students of jazz—all providing a deeper recognition of the humanity and genius of the man.”

—Renee Rosnes, Juno Award-winning jazz pianist and composer

.

.

About the authors

.

Joe La Barbera has performed with world-class jazz artists including Bill Evans, Woody Herman, Chuck Mangione, Michael Brecker and Toots Thielemans. From 1993 until 2021 he was on the faculty of the California Institute of the Arts. He resides in Woodland Hills, California. Charles Levin has written for the Ventura County Star, DownBeat, Jazziz, and the Monterey Jazz Festival Program. He has a BFA and MFA from the California Institute of the Arts and played drums professionally for thirty years. He lives in Ventura, California.

For more information about the book visit the website by clicking here

.

.

___

.

.

This 28 song Spotify playlist includes selections during the time written about in La Barbera’s book. Additional pieces feature other notable groups in which La Barbera has subsequently played

.

.

___

.

.

This interview was hosted by Bob Hecht, and took place on February 24, 2022. Bob frequently contributes his essays, photographs, interviews, playlists and personal stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. He has a long history of producing and hosting jazz radio programs; his former podcast series, The Joys of Jazz, was the 2019 Silver Medal winner in the New York Festivals Radio Awards.

.

.

all photos used by permission

.

.

.