.

.

photo by Sarah Klock

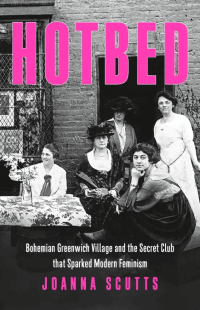

Joanna Scutts, author of Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism [Seal Press]

.

.

___

.

.

…..Few social movements in world history rival that of women’s suffrage, the right of women to vote in elections. At the beginning of the 20th century, the National Woman’s Party led by suffragist Alice Paul became the first movement to picket outside the White House. President Woodrow Wilson ignored the series of protests for several months, and when the demonstrators carried a banner in front of a Russian delegation visiting the White House in 1917 reading, “We women of America tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty million women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement,” it led to arrests and, for some, jail time. Wilson finally changed his position in 1918 and advocated for women’s suffrage as a war measure, which opened the door to the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment – granting women the right to vote.

…..While the suffrage movement is the most prominent example of women advocating for social change, they participated in many other causes – campaigning for better working conditions for garment workers; protesting America’s involvement in World War I; redefining marriage and divorce; and promoting birth control among them.

…..In 1912, a group of powerful Greenwich Village women at the eventual core of these advocacies began meeting regularly. Their group became known as “Heterodoxy,” whose members were fired up by a desire to change their world.

…..In Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism, the author Joanna Scutts writes that Heterodoxy was a “secret social club for ‘unruly’ women that met regularly for twenty-five years,” and who “deliberately kept no records of its meetings, to leave its members free to discuss their lives, their works, and their politics openly.” Its members “were socialites and socialists, reformers and revolutionaries, artists, writers, and scientists…rooted in the vibrant bohemian world of Greenwich Village, [Heterodoxy] was a springboard for parties, performances, and radical politics. But it was the women’s extraordinary, enduring friendships that made their unconventional lives possible.”

…..Hotbed is a captivating, compelling, well-researched, and strongly recommended account of this bold assemblage of women, whose audacious ideas and defiant acts transformed feminist theories into a way of life and a vision of future liberation.

…..In a September 29 2022 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Ms. Scutts talks about this group that was united by a revolutionary belief that “women were fully human and fundamentally equal to men,” and who “became public ambassadors of a brand-new philosophy; feminism.”

.

.

___

.

.

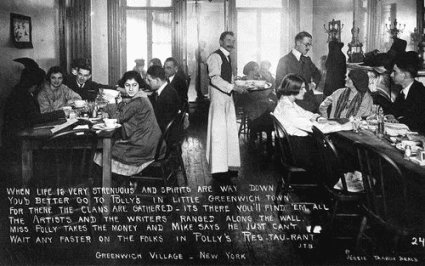

photo by Jessie Tarbox Beals/c. 1910’s

Polly’s Restaurant (run by the anarchist Polly Holladay), the Greenwich Village site of the first meeting places of Heterodoxy

.

…..“There are twenty-five charter members of Heterodoxy, one of whom is so proud of that distinction that she says she wants it carved on her tombstone. Most of them are public figures, in the way that women in professional fields at the time could often be, purely for doing their jobs. For being, if not the first or the only woman in their profession, then among the first and among the few. The majority are college-educated – placing them among a tiny, elite percentage of American women – and several hold even rarer graduate degrees in law, medicine, and the social sciences. There are pairs of sisters and pairs of lovers, women entwined by family and marriage; and those who have studied together, worked together, and marched side by side for the vote. They already know each other by reputation, if not personally – an expose of the group calls it the “de facto star chamber council of the prominent women of New York. Together, in that room, they represent something new, and they know it.”

…“As I look round and see your faces –

…The actors, the editors, the businesswomen, the artists –

…The writers, the dramatists, the psychoanalysts, the dances.

…The doctors, the lawyers, the propogandists [sic]

…As I look round and see your faces

…It really seems quite common to do anything!

…Only she who does nothing is unusual.”

……..-Paula Jakobi entry, “Heterodoxy to Marie” scrapbook

…..“Forging such exceptional lives, well outside the mainstream of expectations for women of their era, can feel daunting and isolating. It is easier in the company of others.”

-Joanna Scutts

.

.

Listen to the 1916 recording of Anna Chandler singing “She’s Good Enough to Be Your Baby’s Mother.” Click here to read the lyrics

.

.

JJM Your book is about a group of Greenwich Village women who, in the early 20th century, were part of a group called “Heterodoxy” that was at the forefront of the era’s most important movements for social and political change. What drew you to this story?

JS It felt like a story that I hadn’t read before, and was one that had existed only in pieces. I first came across it when I was working for the New York Historical Society, which is the oldest museum in New York City. While I was working there we opened a new Center for Women’s History, so I had the opportunity to do a lot of research into the early history of feminism, including working on an exhibition marking the 100th anniversary of suffrage in New York State, which was passed in 1917 – three years before the passing of the 19th Amendment that gave women the vote nationally.

We wanted to do something a little bit different that would speak to our place in the city, and my colleagues and I started researching Greenwich Village and the overlap between the suffrage movement and all of the other radical social justice movements that were centered in the Village. During this research we kept coming across these very interesting women whose stories touched not only on suffrage, but also the peace movement, the labor movement, movements for racial justice, and various other social fights. They were part of this club called Heterodoxy, which had popped up in a lot of histories but never much more than a couple of pages that would note its existence. It made me want to dig into who these women were and to tell their story in a more complete way, to understand what drew them to the Village, and to learn how it was that all these movements for social change were overlapping and feeding each other during this time.

JJM Heterodoxy didn’t keep records of their meetings, so what sources were you able to use to tell this story?

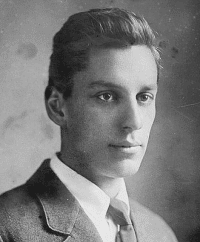

Marie Jenney Howe (in a c. 1914 photograph), was a Unitarian minister, suffrage activist, and writer. She was also the founder of Heterodoxy, who first met as a group in 1912

JS This is an example of why this isn’t familiar history, because nothing exists about who they met with or what they talked about. The clue is in the name of the club – the idea of Heterodoxy was that women could come with differing opinions and views and hash them out without worrying that anything they said would be recorded for posterity. The members were prominent public figures so they had reason to think that whatever was said in the meetings could be a part of the public record, which is not what they wanted. But because of the lack of an archive, the importance of the group hasn’t been understood.

There was a lot written about the club, and much has been written by the members of it – for example, many of them wrote memoirs that mentioned Heterodoxy or their friendships within it. Archives exist for the individual women – some of the more prominent women of Heterodoxy have left a pretty good paper trail – and there has of course been much written about Greenwich Village, often by men with whom some of the women were friendly or romantically involved with. So, they left their mark in this sort of secondary way, which allowed me to dig into that wealth of literature and chase the story.

Although I love archival research, I’m not actually a historian by training, but I am a literary scholar and very interested in cultural history, which means I approached this book from that perspective. I’m happy to look at their literary work and read what these women wrote about their time and place. There are many threads to this story – drama and playwriting and acting, for example, because many of the women were involved with the theater – and much of the research and fun was in chasing down many of these threads.

JJM How far outside the mainstream of America were the women of Heterodoxy?

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Mabel Dodge Luhan portrait by Carl Van Vechten, 1934

JS Pretty far outside. Some had led more outwardly conventional lives than others, but one place that really came through very obviously was in regards to marriage and divorce. In the 1910’s, when much of this story takes place, the divorce rate in America was about 3%. Divorce was very rare, difficult, expensive and scandalous, but within the Heterodoxy club, one-third of its members had been divorced, and several of them were divorced multiple times. One fascinating character is Mabel Dodge Luhan, who was married four times and was a somewhat notorious figure on that basis alone, but she wasn’t alone because several members had multiple marriages. And, several women were openly – at least within the club – in lifelong relationships with other women, so their private lives were definitely outside of the mainstream of America.

JJM How did the men in their lives feel about Heterodoxy?

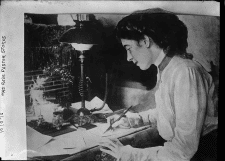

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Max Eastman (date unknown)

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Crystal Eastman, during the time she was married to Wallace J. Benedict (between 1911–1916).

JS It varies, but many of the men were quite supportive. Some were very famous men who left their mark on the history of the Village and who were either involved with or married to women in Heterodoxy. One of the best-known men is Max Eastman, the editor of The Masses magazine. His older sister Crystal Eastman – who was married twice – worked with him and was instrumental in getting him started in publishing. He was an outspokenly feminist man who wrote articles about what it meant to be a feminist and why it was important. He was also one of the organizers of a group started in the Village called the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, so he was an example of a progressive-minded, avant-garde thinker who was supportive of feminist ideas and of the club. He was married for awhile to one of Crystal’s friends, Ida Rauh, who was a member of Heterodoxy at the time. She decided to retain her surname at the time their marriage was announced, and this news actually made the newspaper at the time, and in the article Max supported her decision, saying that she is her own person. So, there were some symbolic gestures that had the support of their men but which also captured the imagination of journalists.

It tended to get more challenging for men to show their support when children were involved, because as forward-thinking as they wanted to be, there were culturally ingrained ideas about how young children were to be cared for, and by whom, and they had no model for a version of a family where men were actively involved in parenting. This was one of the factors that broke up Max’s marriage to Ida – they had a child, and the idea that she wanted to continue working and continue her activism didn’t fit any vision of a family Eastman knew, even though these were mostly quite wealthy people who had often been raised with the help of servants. Even supportive men thought women were naturally predisposed to care for young children, and to want to stay home with them, which is where the principles and the reality ended up clashing.

JJM So many of the issues advocated by the women in Heterodoxy are still being fought – for example, equal pay for equal work, abortion rights…

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Margaret Sanger, 1922

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

The suffragette Mary Ware Dennett, 1913

JS Yes. Since the time that the book came out in early June the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade came down, and abortion and having access to birth control was absolutely central to these women’s lives, and to their activism. Advocating for it didn’t work in the same way as some of the other issues. Suffrage, for example, involved marching in the streets, but even though Heterodoxy was involved in that fight, nobody was really marching the streets for birth control.

We remember Margaret Sanger as the founder of the American Birth Control League – which eventually became Planned Parenthood – but she wasn’t the only person working for birth control. One of the women in Heterodoxy, the activist Mary Ware Dennett, was the founder of a group called the Voluntary Parenthood League, and she focused on birth control and sex education. Her husband divorced her against her wishes, which became very public and scandalous, and she was left to raise two teenage sons on her own, during which time she wrote a no-nonsense pamphlet about sex for her sons that became something people asked her to print and circulate. It’s a very open and straightforward guide for young children, but she was prosecuted some years later for obscenity. By the time it went to trial she was a grandmother and the cultural tide had already turned, so it seems ridiculous that this grandmotherly figure would be hauled into court for an obscenity charge. It’s a reminder that wherever you think the mainstream is, there are currents pulling it in in other directions.

JJM The United States Postal Service and its Postmaster General at the time, Anthony Comstock, played an outsized role in the issue of birth control…

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Anthony Comstock

JS Absolutely. Comstock was an extraordinary figure; a real single-minded zealot. He was in that position for decades, and during that time spearheaded laws that were on the books for decades after he died. He was there to crack down on anything he considered to be obscene, so his influence over the mainstream culture was quite extraordinary, and his tangles with Margaret Sanger over the issue of birth control are pretty well-known. The idea that the Postal Service would have anything to do with healthcare seems strange to us now, but it had this power at the time because it could control the distribution of information, so for the women of Heterodoxy the issue of birth control was a free speech issue as much as a medical one. Providing services and contraceptive devices was one thing, but much more fundamental was that women wanted to know how their bodies worked.

JJM At the turn of the century, Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote a book titled Women and Economics. You describe her as the “most famous public feminist of her time,” and her book a “Bible for progressive young women.” How was this book an inspiration for the founders of Heterodoxy?

JS By the time her book was published, Charlotte Perkins Gilman was already somewhat of a notorious public figure. She’s somewhat known today, but mostly as a novelist. Women and Economics was her attempt to point the way towards a complete reimagining of society that would allow women to fulfill their personal and intellectual potential. She and many of the other feminists in Heterodoxy were interested in that because, essentially, women’s lives and development had been thwarted, and they wanted to explore what happens when women could be fully human, and if they weren’t denied an education and kept back from the opportunities that white men enjoyed at the time.

The idea of “women and economics” seems innocuous to us now, but at the time connecting women and economics was a new thing, and her point was that women can’t just be given the vote and one or two symbolic rights that they otherwise haven’t had, it would also require people to rethink how society is structured. If women were going to develop their potential then it would require a rethink of how children would be cared for, and she had a vision of making childcare and domestic work professional work, and to recognize it as an important part of the economic system. She was a member of the Socialist Party, so this vision became a discussion about the redistribution of resources and making sure that women workers had a place within the economic system. And that’s what transforms the way that the early feminists thought about many of these issues, and how they started to see the suffrage movement as just one strand in a much broader need for reform.

JJM A fascinating part of the story is how the women of Heterodoxy – and women in general – influenced the labor rights movement, particularly the garment workers after the Triangle fire. What did their involvement in the labor rights movement look like?

Triangle Fire; New York, March 25, 1911

JS Greenwich Village is located very close to the Lower East Side, which at the time was the center of the garment industry, and where enormous immigrant populations worked and lived. There were hundreds of factories there, and there were also smaller factories in the Village, so this environment in which many women worked was very visible to the women of Heterodoxy. The idea of women staying home to raise children while their husbands went to work obviously didn’t apply to poor families living in downtown New York. Factory work for men didn’t pay enough for to support a family which meant many women needed to work also. People lived in family groups, and a major source of wage earners were young, unmarried women – daughters and sisters were a key part of the workforce – but they were being left out of the conversation by the labor unions, which focused on skilled labor and didn’t take into account women who moved from factory-to-factory, and who weren’t seen as being part of a stable workforce or easy to organize. The women workers themselves were organizing and starting to participate in smaller strikes, and the Triangle Fire of 1911 was a hugely galvanizing event for raising awareness of worker safety and changing the idea of who the worker was since the victims were overwhelmingly young, immigrant women. This awareness meant that people understood the need for worker’s protections.

photo via Library of Congress

Rose Pastor Stokes, 1910

.

photo via Library of Congress

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, 1910

Two women of Heterodoxy were particularly active in the labor movement. One, Rose Pastor Stokes, was a socialist who worked in cigar factories as an immigrant and who married a millionaire, which was a big social scandal at the time. Her husband Graham Stokes was involved in social reform and they worked together for a long time within the socialist movement. The other was Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an important and overlooked figure who was an organizer with the Industrial Workers of the World at a time when the I.W.W. was a real force in American political life, and their version of organizing was more effective in terrifying factory owners than in improving working conditions, but their work made labor an issue that was impossible to ignore in the culture and within politics. Their vision of a union was for every worker – Black, white, skilled, unskilled, male, female, and in whatever position within the hierarchy of labor – needed to come together and assert their power as workers collectively, so they became a real vocal force within the labor movement.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s involvement in Heterodoxy is really quite striking because she initially didn’t believe that women working together was important; instead, she thought that what mattered most was social class and alliances along class lines. She didn’t think she had more in common with rich women, just because they were women, than she did with working-class men, but then, after some time in the labor movement, she realized that solidarity with women and forging relationships with them across class lines was important. Her involvement really changed the tenor of the discussions because she was there on the frontlines, organizing women all over the country.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1919 recording of James Reese Europe and the 369th Infantry Hellfighter’s Band playing “On Patrol in No Man’s Land.” Noble Sissle is the vocalist.

.

JJM When we think of what women advocated for during the early 20th century, we tend to think of suffrage, but there are many other issues they had influence on, and labor reform is a great example of that. Your book is a tremendous resource for understanding women’s roles on affecting change during that time. Another example was their resistance to World War I…

JS Yes, that’s an important part of the story. It is interesting because, historically, women have been a central part of peace movements due to the authority they had as mothers who nurture and protect their sons and who’d oppose sacrificing them to war. There are deep-rooted gender ideas when you think of men’s and women’s roles in war. So, there is this tradition of women being resistors to war, but in the buildup to World War I, that was a risky thing to do, and the women of Heterodoxy – many of whom were pacifist by conviction – were taking an active, more confrontational role in resisting a war between European capitalist powers who they saw being as interested in expanding their empires as much as feeling any kind of moral justification for it. So, they were pointing out uncomfortable facts about the way the war was being waged and the British colonial motivations for it – arguments that made these connections explicit. They weren’t merely saying they were against the war because they were nurturing women and opposed the killing of their sons, they were saying they were against it because it was a squabble over capitalist resources and the only people dying were the workers, so it should be resisted on the grounds of a socialist solidarity.

A testament to the boldness of these women is that they were doing so in the midst of much vitriol – especially once the United States entered the war – and while a crackdown by the government for this kind language was becoming more visible and intense. Their war resistance was bound up in Socialism and in other movements, and in wanting to re-think society so it wasn’t so vastly unequal, in which the power and the wealth was concentrated in a few hands while the working and the dying was being done by vast numbers of disempowered men and women.

JJM The idea of embedding socialism with suffrage activism and, as you wrote, “to challenge [Heterodoxy] to consider the full spectrum of exclusion and oppression in American society” had to be on the radar of the government…

JS The years 1917 to 1922 was a period of enormous government crackdown on dissent, on left-wing activism, and on free speech. There was so much official and unofficial surveillance that was designed to watch people and keep them in line, and women in Heterodoxy were being surveilled, and some were even arrested. Rose Pastor Stokes, for example, was arrested for giving a speech that was judged to be anti-war. One of the members of the club, Fola La Follette, was the daughter of a senator from Wisconsin, Robert La Follette, who was the most vocal anti-war advocate in the Senate and who was an antagonist of President Wilson. He was considered a notorious national figure, so Fola was being followed and watched. And Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was arrested constantly because of her work with the I.W.W.

Once America entered the war the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act restricted free speech and shut down newspapers and magazines suspected of being anti-war. This kind of repression continued long after the war was over, and it served to break the back of the socialist movement as a political force in the country. While there was a Socialist Party, the women weren’t necessarily affiliated with it, they were just believers in the idea of socialism and seeing it as a way to address the massive inequality in American society. So, to the women of Heterodoxy the idea of socialism and feminism being naturally connected was obvious to them, but as we know, people promoting socialism were considered disloyal to the country, and we have never really lost that.

JJM And Greenwich Village was a hotbed for socialism…

JS Absolutely, but it was more of an embrace of socialism as an ideology rather than a political affiliation, although Eugene Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party, ran for president several times and garnered almost a million votes. He was a prominent and beloved national figure, even after they threw him in jail, but he wasn’t the only leader of that group. And certainly for the women, before they could vote the idea of having a party affiliation wasn’t as important as socialism meaning something – it was more of an identity that said you were interested in finding ways to reduce inequalities and hierarchies in all kinds of areas. For example, they worked on how to make marriage and relationships between men and women more equal and better for both men and women. That seemed to come under the idea of socialism, and it was an idea prized by many who lived in Greenwich Village.

JJM It is interesting to read about how the women of Heterodoxy used their creativity for advocating for change…

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Lou Rogers, c. 1910

.

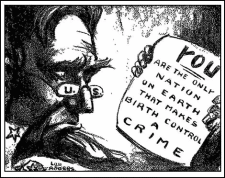

Lou Rogers’ cartoon that appeared in Birth Control Review, 1918

.

JS Yes, that’s a big part of their work, this idea that there was no separation between politics and creativity. The political cartoonist Lou Rogers was a very visible figure in the suffrage movement, and she created, for example, witty and forthright cartoons dealing with birth control. There were many professional actresses in the group who performed roles in the support of suffrage, and there were many plays and skits and pageants – one of which, the Paterson Pageant of 1913, was intended to raise funds for the striking silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey. They brought hundreds of striking workers into Manhattan and they paraded to Madison Square Garden, where prominent Village artists, including many women in Heterodoxy, staged a pageant that was an attempt to expose the plight of the workers to wealthy audiences in Manhattan. It wasn’t successful as a fundraiser, but it was an attention-grabbing artist moment that has since passed into legend.

Initiatives like that show how much overlap there was between these movements and how open they were to anything that would grab attention, change the dynamic, and involve people whose literacy and education levels would not allow them to understand the issue in writing, so they created visuals like parades and pageants to help organize them. Performance allowed them the opportunity to expose their issues in a way that was easily understandable to a huge audience, and using creativity was a big part of that. The visual and literary inventiveness contribute to making this such a vibrant history to study.

JJM You wrote, “In the wake of the suffrage victory in 1920, the fragile unity among the different forces fighting for women’s rights splintered. Feminists and women’s rights activists disagreed on where they ought to focus their fight moving forward.” What were some of their disagreements?

Women suffragists picketing in front of the White house, 1917

JS The final push to ratify the 19th Amendment was so singular that it brought in many different groups, all of whom had the sense that this one big thing needed to get done. They were putting pressure on President Wilson, and there were certainly disagreements in the ranks over whether that was the right approach. Once the amendment finally passes and is signed into law, women were able to vote in the presidential election in 1920, which resulted in a Republican landslide. It is interesting that the final push for the amendment came from the Republicans who felt that they would win the election if women were given the right to vote.

Following this there is a shift in the sense of urgency, and much of the fight goes out for a lot of women. On the face of it, the suffrage movement – the fight for the vote – is a very simple question and one that was widely supported and agreed to at the time. But following that the question became “now what?” While women got the vote they were still lacking many basic rights, but it was hard for them to get the same level of attention. They had been so focused on this one goal, and once they got it there was a period of deflation and a time of questioning what to focus on next.

During the post-war period a lot of attention was turned toward international politics and how to prevent the next war, how to deal with the aftermath of all of the soldiers coming home without jobs, and how to respond to the racial clashes that occurred when Black soldiers came home to violent confrontations and attacks by whites on their neighborhoods and people. These issues were at the forefront of the conversation, so priorities shifted and it felt as if they fractured women’s unity as a group under the suffrage banner. So, they were still fighting and advocating, just in different ways, and their disagreements became more visible, which made it look as if the result was a dissipation of energy.

JJM What would you like readers to take away from their experience of reading your book?

JS I hope it makes them curious about this period of history, which is so turbulent and transformative and has so much resonance with today, a century later. There are things in the book that will feel surprisingly urgent and contemporary to readers – for example, how to respond to issues of social and economic inequality and injustice.

The other thing is that the thread that I was initially drawn to about Heterodoxy is the way in which these very different women came together as friends, and how their network of friendship helped them to forge these very unusual, independent lives. Although my book only goes up to the early 1920’s, Heterodoxy was operating and meeting almost until World War II, so there is a real longevity to this group – 25 years, when most Village clubs lasted 12 months at the most. So, there was this very long and very deep connection within their network of support, and I always found the importance of their friendships and community and its impact on the world to be very moving and inspiring, and something we don’t get enough of a sense of in history. We get so many individual stories in history but we don’t hear enough about stories of groups working together in a collective spirit that is inspirational.

JJM So it’s a history that modern day activists can potentially learn from…

JS Yes, in a way that friendship and creativity and community can involve people in change. People tend to get involved in advocacy because of events of outrage and horror, so it is nice to think about people joining movements because their friends are doing it and are making it fun. It involves people in a different way and lets them feel as if there is a positive movement for change, and for correcting injustice.

.

.

Library of Congress

Heterodoxy members Doris Stevens, Alison Turnbull Hopkins and another elite suffragist, Eunice Dana Brannan, during their detention at Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia.

.

“Together, the women of Heterodoxy pushed each other toward a new way of living. Everything from the way they dressed to the company they kept and the causes they championed was self-consciously new, and the daily pursuit of the future could be exhausting. They needed each other: as inspiration and support, as friends and lovers and rivals. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a leader since her teens in the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a believer in class solidarity above all, was at first skeptical of the benefits of a women-only organization. Her membership in Heterodoxy proved to be a transformative experience. ‘It has been a glimpse of the women of the future, big spirited, intellectually alert, devoid of the old “femininity” which has been replaced by a wonderful freemasonry of women,’ she wrote. She referred to the club as ‘this charmed circle,’ a group touched by magic.”

-Joanna Scutts

.

.

___

.

.

Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism [Seal Press]

by Joanna Scutts

Joanna Scutts is a literary critic, historian, and author of The Extra Woman. She has written for the New York Times, Washington Post, New Yorker, and the Paris Review series “Feminize Your Canon.” She holds a PhD from Columbia University and lives in New York.

.

.

___

.

.

Praise for Hotbed

“Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism is a spirited, inspiring history of a little-known enclave of feminist movers and shakers in an expertly evoked early twentieth-century Greenwich Village. How I long to visit! But then, reading Scutts’s book, I almost feel as if I have. Deeply researched and deftly rendered, Hotbed is a must-read for anyone seriously interested in feminism, feminist history, and the power of the city to help women change their lives.”

—Lauren Elkin, author of Flâneuse

.

“An enlightening contribution to the history of feminism.”

—Kirkus

.

“[A] lively and absorbing new social history… it was only after I read Hotbed that I realized the type of feminist friendship from which I am more directly descended was that of the Heterodites.”

—Vivian Gornick, New York Review of Books

.

“In Joanna Scutts’s capable hands, the individual lives of the members of the Heterodoxy Club become a prism through which to examine the defining issues of New York City in the early 1900s, from suffrage to workers’ rights, from racism to sexism. Incredibly resonant in today’s times, and a profound read.”

—Fiona Davis, New York Times–bestselling author of The Lions of Fifth Avenue

.

“Revolutions often begin in unlikely places, and Joanna Scutts, with verve and a historian’s eye, captures the moment that gave birth to modern feminism…No records of the meetings were kept, to allow folks to speak their mind, which makes Scutts’ achievement in piecing together Heterodoxy and its impact even more remarkable. Hotbed is its own landmark of a struggle that persists today, whether it be about abortion or sexual harassment or workplace inequities.”

—Air Mail

.

“A fascinating view of feminist activism at the beginning of the 20th century.”

—Library Journal

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on September 29, 2022, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to click here to read our interview with Emily Yellin, author of Our Mother’s War: America Women at Home and at the Front During World War II

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support Jerry Jazz Musician

.

.

.