.

.

photo courtesy Jeff Gold

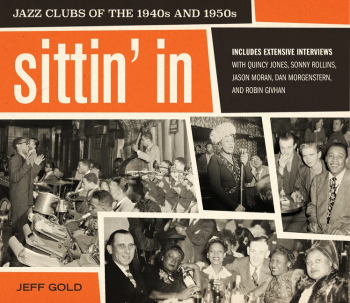

Jeff Gold, author of Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s (Harper Design)

.

___

.

.

…..Jazz fans have long imagined what it must have been like to take part in the golden age of the music – dancing in the grand ballrooms of the swing era, club-hopping 52nd Street, making the scene on LA’s Central Ave, taking in Monk and Coltrane’s second set at the Five Spot. These countless musings inhabit large portions of a devoted fan’s inner world, informed by the great photographs the likes of Gottlieb, Claxton and Leonard took in America’s dark, often subterranean jazz clubs, thick with smoke and booze and genius.

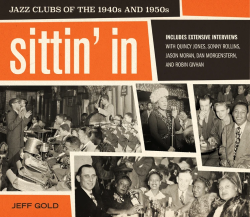

…..The rich atmosphere of these clubs and the music emanating from them has been studied by historians and musicologists for decades, and as we know, the events within these settings helped transform American cultural life. But also, as we read in Jeff Gold’s Sittin’ In: The Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s, the jazz nightclubs were among the first places that opened their doors to both Black and white performers and club goers during the time of Jim Crow.

…..So, what was it like in these clubs? In one of the book’s five impressive interviews, the legendary saxophonist Sonny Rollins – who as a young musician took part in the club scene – tells Gold that it was “a paradisiacal place to be,” and tipped his cap to the audience, who provided energy to the musicians. “In a small club…the people are closer to the stage. And they sort of played with you. They’re like part of the band…that inspires everybody to play. Because it’s a big community jazz fest, and you have to be good, you have to take your best product in there when you’re playing close to people.”

…..A former major label record executive and, according to Rolling Stone, one of five “top collectors of high-end music memorabilia,” Gold came across a rare collection of jazz club posters, handbills, menus, branded matchbooks, and – the centerpiece of the collection – photographs of club patrons who were captured by the house photographers who roamed the floor and, for a dollar, provided them with a souvenir of their evening, neatly enclosed within a keepsake folder with the club’s name and logo. In his superb book, Gold writes about how these photos provide new evidence about the scene, who took part in it, and its fascinating social essence, particularly its role in influencing a complex racial era.

…..In a February 26 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Gold talks about his book and the rare collection of 200 full-color and black-and-white souvenir photos and memorabilia that bring life to the renowned jazz nightclubs of 1940’s and 1950’s.

.

.

Unless otherwise noted, all images © Jeff Gold, and are published with his consent

.

.

_____

.

.

.

“Back then, it wasn’t about color in the clubs, it was about how good you can play. Racism would’ve been over in the 1950’s if they’d listened to jazz guys.”

-Quincy Jones

.

.

A 1945 souvenir photograph from New York’s “400” Restaurant. The “400” – on Fifth Avenue at Forty-Third Street – was a ritzy supper club best remembered for hosting a series of live coast-to-coast radio broadcasts featuring Duke Ellington and His Orchestra. The photo is of a soldier, the actress Joan Davis and Ellington.

.

.

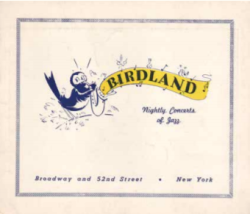

Listen to a live 1954 recording – from New York’s Birdland – of Art Blakey playing “If I Had You,” with Lou Donaldson (alto sax), Clifford Brown (trumpet), Horace Silver (piano), Curly Russell (bass), and Blakey (drums).

.

JJM Tell me a little bit about your background, Jeff…

JG My parents brought me a copy of The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” after returning from a Palm Springs vacation, and I flipped out for it. I watched them on Ed Sullivan and went so music crazy that I used to fall asleep with a little transistor radio under my pillow. The second record I fell in love with was The Lonely Bull by Herb Albert and the Tijuana Brass. I ended up working for Herb and meeting Sol Lake, who wrote that song, which I still love.

So I’ve been obsessed by music and was able to turn it into a career. I was the first employee at the Rhino Records store in Los Angeles, and subsequently worked for record companies for 20 years, including as Executive Vice President and General Manager of Warner Brothers. When I was in high school and college I would buy rare records and resell them to support my music habit and make some money, and I went back into that in a big way when I left the record business. My time is now occupied by buying and selling rare records and music memorabilia, and writing books on music related topics, as well as consulting for various music business projects. I have appraised the Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen archives for their management teams, and also worked with Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones. So, I periodically do things like that. I have also helped the Experience Music Project in Seattle organize shows, and since its inception I have been a major donor of memorabilia to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. I am just obsessed with this stuff.

JJM Are you contributing anything to the National Museum of African American Music that recently opened in Nashville?

JG Peripherally, yes. I sold them one thing about a year-and-a-half ago, and I steered a collection to them that they’re likely going to acquire.

JJM Your book is more of a social history than it is a musical history, and it’s a story centered on a fascinating collection of jazz night club memorabilia. How did you discover this collection?

JG Because of my business I’m called periodically by people who want to sell their collections of records or memorabilia. Sometimes they’re a complete waste of time, sometimes they can be the mother lode, and usually they’re somewhere in between. The guy who had this stuff had collected jazz memorabilia seriously for 35 years, but his tastes were beginning to change so he was getting into collecting other things. He got in touch with me and told me he was thinking about selling a collection and asked if I would be interested. I of course was and went to his house where he showed me a few things, and then took me to his bank, where the collection was stored in five or six safe deposit boxes, all filled with just incredible stuff. None of it was organized. It seemed as if when he bought something he would just put it into a pile with the newest arrivals on top, so it was organized chronologically in the order he acquired it.

Birdland souvenir photograph with frequent patron Marlon Brando (right) posting with clubgoers, date unknown

.

Birdland photo folder

.

Birdland souvenir photograph with Dizzy Gillespie (third from left) posing with fans, date unknown

I started going through a box and found just a wealth of amazing stuff, things like 10 pictures of Charlie Parker, or concert tickets from 50 years or so earlier, and even signed contracts. Then I went through souvenir photos from places like Birdland. While I’d seen stuff like that from hotels and just generic night clubs, I hadn’t seen them from jazz clubs, and as I was going through it I was putting things that I wanted to buy off to one side. After an hour I had put aside about 40 of these souvenir photos. I had literally never seen anything like this – the nightclub artwork is so great, and there were also photographs of people like Dizzy Gillespie posing with fans at Birdland. Even as I was going through the safe deposit boxes, I had the thought that people need to see this memorabilia, and it would make a great book!

I made about three trips back to the bank over a year-and-a-half to see the collection, and over that time ended up with about 150 souvenir photos. I had sworn I was never going to do another book because it is just so much work. My first book was on classic rock on vinyl, and I said to wife when it came out that I have now mastered the art of making $4 per hour. It was a really successful book that went into four printings, so I revised that to now mastering the art of making $20 per hour.

While I said I would never do another book again, I had a pile of these photos sitting right next to me in my office, and I was engaged in a staring contest with them. Periodically I would go on the Internet to see if I could find any collections of these from jazz clubs anywhere and I couldn’t – only occasionally would I find one or two on a website. Then I started researching jazz clubs and discovered that there aren’t really any comprehensive books about them. Eventually, because I am a history nut and obsessive about music, I thought people need to have an opportunity to see this collection of artwork, handbills, tickets and all the memorabilia that are so evocative of this incredible time.

JJM How many of these individual assets did you end up using in your book?

Charlie Parker with fans at the Royal Roost, late 1940s

.

.

A souvenir photograph of Billie Holiday at Bop City, date unknown

JG There are approximately 220 illustrations in the book, 75% of which came from this one collection, and the other 25% of them were found elsewhere. My favorite picture in the book is of Charlie Parker sitting with a couple at the Royal Roost, which I found in an autograph auction. I bid on it but it sold for something like $10,000, so I asked the auctioneer if they could contact the buyer on my behalf and give me permission to use the photograph, which they very graciously consented to do. So the bones of the book come from this one collection and I filled it out as I could, and I licensed four or five photographs as well.

JJM One of the photographs is of Billie Holiday at Bop City in New York, which may be the most exquisite picture I’ve ever seen of her.

JG I agree. It’s interesting, in almost every case we know virtually nothing about the people in the photographs, or the people who took the photographs. But that photo of her must have been a result of someone in the club asking the photographer to take a picture of Billie Holiday, which was probably then purchased from the photographer. [Jazz journalist and historian] Dan Morgenstern told me that one day Louis Armstrong showed up at the Metropole night club, and Dan – who was working for Metronome at the time – got the in-house photographer to take a picture of Armstrong sitting with musicians. So, while most of these photos were of audience members in their own parties, on occasion there are photos of musicians like Dizzy Gillespie posing for a picture with them.

JJM Yes, there are some really nice photographs of musicians in the book, but there are already many wonderful books of jazz musicians by people like William Gottlieb and William Claxton and Herman Leonard. What makes this book unique is that at its core are photos of patrons taken in these legendary clubs, which makes it attractive from a social history standpoint. You also augment these photographs with interviews you hosted with Quincy Jones, Sonny Rollins, and Dan Morgenstern – who were old enough to have personal experiences in these clubs – as well as contemporary pianist Jason Moran and the fashion critic Robin Givhan, who each brought their own expertise into interpreting the historical significance of the photos. So, what struck you about the photographs of the patrons?

Souvenir photograph of World War II servicemen at the Onyx Club, New York, mid-1940’s

.

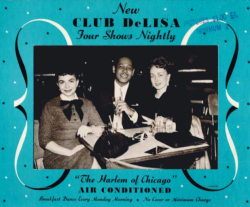

Souvenir photograph from Chicago’s Club DeLisa, date unknown

.

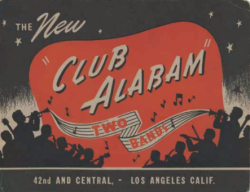

Club Alabam (Los Angeles) souvenir photo folder (above) and photo (below); date unknown

.

JG The first thing I realized was that when you look at the photographs from people like the esteemed photographers you mentioned, they are almost always of the performers on stage, or of the marquee outside, or of the people standing outside so you can see the club’s awning. Of all the wonderful photographs taken by Gottlieb – which are now, at his direction, in the public domain – only a handful have audience members in them, so the first thing that dawned on me was that these photographs really are a social history. And then I thought about how these photos are a result of the camera being turned around, taken from the performer’s point of view. It is what they would have been looking at, and we never see that – as much as clubs like Birdland have been documented, we never see the people who went there. I found that to be incredibly interesting.

That led me to thinking that I should interview some people who were there. Because I once worked for Warner Bros. I’d met Quincy Jones and I knew people who were very close to him, which helped me arrange for the interview, and he was the first I did for this book. During the interview I casually asked him what the racial situation was like in the clubs in the early 1950’s – about the time he arrived in New York – and he said that everyone got along great, that there was really no racism in the clubs and that people just paid attention to the musicians. That answer was totally unexpected, and it really threw me for a loop, but he was there and I wasn’t.

My next interview was with Sonny Rollins and I decided to tell him what Quincy said and see what his read on that situation was, and it was almost as if I unlocked something he’d wanted to talk about for years. He kind of went on a tear about how jazz musicians never got credit for what an integrated scene it was. Here was this Black man who grew up in Harlem and didn’t have much interaction with white people at the time, but in the clubs they were coming up to him to say how great he was and asking for his autograph and to pose for a picture with them. It was mind blowing for him, and it really surprised me to hear this, and it made me want to explore it more deeply with him.

JJM These are interesting interviews…

JG Yes. Quincy arrived in New York in the early 1950’s as a 19-year-old, Sonny began going to the clubs in the late 1940’s when he was underage, drawing a moustache on his face with eyebrow pencil to make himself look older, and Dan started going as a 17-year-old in 1947, nursing a coke for an entire evening. Quincy is now 88 years old, Sonny is 90 and Dan 91. It dawned on me how fortunate I was to be doing this book now, because in ten years it will be virtually impossible to interview somebody who went to a jazz club in the 1940’s.

JJM Race was a major topic within most of your interviews…

JG I was friendly with the photographer Bill Claxton, and I knew another LA jazz photographer Ray Avery, but I never thought to ask either of them about jazz clubs. They would have been interesting people to talk to but both of them are long gone now. So it got me to thinking that these interviews are my shot to ask anything I want now, and the subject of race relations in the clubs came up, which is something that is very poorly documented. Some people have said I focused too much on it but this was my opportunity to talk with Sonny Rollins, you know?

JJM How could you not talk about it? Jazz had so much to do with breaking down racial barriers, years before Jackie Robinson integrated baseball…

JG Yes, as we know Benny Goodman integrated his band a decade before Jackie Robinson entered major league baseball. Not to take anything away from Robinson, but that was pretty ballsy.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the live 1957 Village Vanguard recording of Sonny Rollins playing “I Can’t Get Started,” featuring Wilbur Ware (bass) and Elvin Jones (drums)

.

JJM In your interview with Rollins he told you that the clubs hired Black musicians “because there’s money to be made,” not because they were looking to integrate…

.

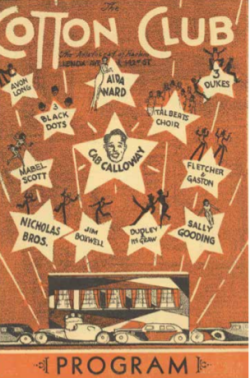

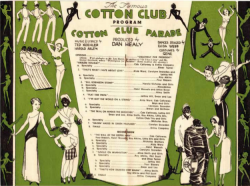

The front and back covers from a program from the 1932 Cotton Club Parade, headlined by Cab Calloway

JG Yes, he was talking about the Cotton Club in particular when he said that, which is the most famous segregated club discussed in the book. And so that was a phenomenon that I explored at length too, just because it’s so odd that this club that hired African American musicians only allowed white people inside. On the other hand, they had one of the first live radio wires, during which time they hired at pivotal points in their careers the likes of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway, who all became famous for doing live broadcasts from the Cotton Club. This allowed them to get better record deals and tour nationally and the Cotton Club paid people well, by all accounts. So, on the one hand this terrible racism is very evident, but on the other hand the club provided positive things for artists. So, when Sonny and I talked about that he said, yes, but don’t be mistaken, the reason they did these things was to make money. Then, when I talked to Morgenstern – who interviewed countless people who played there – he said it was a kind of “deal with the devil” musicians were happy to make because they got paid well and it was so valuable for their careers.

JJM Jazz was a connecting point, in many ways, for Black and white people to get together, and you see that showing up in the book’s photographs. They are just snapshots in time so you can only learn so much from them, but it is comforting, in a way, to see how people’s shared interest in jazz created opportunity for integration within this club environment…

JG As Quincy Jones told me, as a musician nobody cared whether you are Black or white, only whether you could play. It’s fascinating to hear about it and read about it, and to see a picture like the one of Charlie Parker posing with a white couple in a photo taken at the Royal Roost during the late 1940’s. He’s got this sly smile on his face, and the couple looks thrilled, and you realize that at this time Parker is not yet the iconic, world famous musician – to the patrons he is just a hot young musician playing a club in 1948. It made me think, where else would you see Black and white people posing together so happily in the late 1940’s?

JJM There is such a fascination with this era, and jazz fans in particular have an almost romantic notion about all that happened on 52nd Street…

JG Yes, the scene was great. Musicians were breaking down barriers, their recordings are still being listened to, and as you can see from these photographs it was a very stylish era. You can’t help but look at the album covers of people like Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins and see the epitome of cool, musically and visually. It’s like the 1960’s for rock music, when creativity was exploding and iconic artists were arriving seemingly out of nowhere.

JJM The fashion critic Robin Givhan was surprised by the formality of the attire worn by the patrons, and said; “The music might be more rebellious and subversive than what’s happening socially is.”

Well dressed patrons at Small’s Paradise, New York, 1940’s

.

Souvenir photo from Chicago’s Blue Note, late 1940’s

.

Souvenir photo from Chicago’s Hurricane Show Club, 1940’s

JG Yes. I wanted to interview someone who could speak intelligently about the fashion as well as deconstruct the photos and tease meaning out of them. Robin is very good at that. So, when you look at that picture of Charlie Parker, for example, I’m seeing the expressions on their faces, but she is analyzing the fashion and seeing that the pinstripes and lapels on the suit Parker is wearing is different than the suit the guy he’s posing with is wearing. The cut of Parker’s suit is much more exaggerated, and the pinstripes are bolder than that of the audience member, and she thought that Parker probably chose that suit so he could be seen from the furthest corner of the club. That is something I never would have thought about.

To me, the people look like they were wearing their most stylish clothes, but to her it looked as if they were wearing their nicest church clothes. It wasn’t that they were particularly stylish, this was clothing a woman would wear out to a fancy event. So, she was able to give my untrained eye a bit of a reality check about who these people were.

JJM The basement jazz club is a great metaphor for what jazz musicians were doing, which was changing music radically, and doing so in the sanctity and safety of a basement club. Equally interesting is that they were creating what many considered to be “subversive” music while being surrounded by a formally attired audience.

JG Sonny and Quincy and Jason all talked about the escape these clubs provided. There may have been racism up on 58th Street, or racism in the workplace, and the world was in the midst of a world war, but while bebop was emerging, as Sonny and Quincy told me, the clubs were a valuable escape for Black people because for four hours they could leave their troubles behind and listen to this incredibly innovative music while also being treated with some measure of dignity and respect.

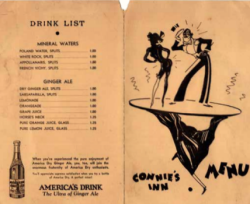

A menu from Harlem’s Connie’s Inn

.

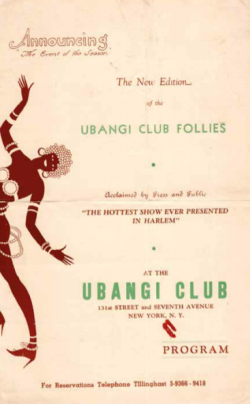

A program from Harlem’s Ubangi Club

.

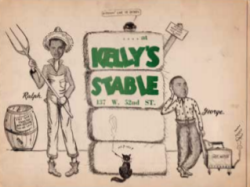

A photo folder from 52nd Street’s Kelly’s Stable

.

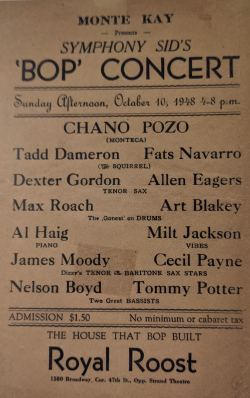

An October, 1948 poster of Midtown’s Royal Roost

.

A photo folder from the Greenwich Village club Eddie Condon’s

JJM About half of the book focuses on the clubs of New York, and you break that into three neighborhoods of Manhattan: Harlem, Midtown, and Greenwich Village. How would you characterize each of those neighborhoods’ club scenes?

JG It was almost a chronological unfolding. The scene starts off in Harlem in the teens and 1920’s, and there are a number of integrated clubs there at the time – the Cotton Club being a segregated club was the exception rather than the rule. Harlem clubs like Small’s and Connie’s Inn were integrated in the 1920’s. The scene changed because of the race riots in Harlem in 1935, and a lot of the white people who came there from Midtown and downtown don’t’ feel comfortable doing so anymore. As a consequence, business starts dying down and some of the clubs like the Ubangi and the Cotton Club move downtown. Small’s continued to thrive, but others, like Connie’s Inn, are forced to close.

The scene moves to 52nd Street, and it starts off as a swing-based thing, but as bop emerges 52nd Street becomes the dominant hub for that music. So, along the street and around the corner, where Birdland and the Royal Roost were, there is a concentration of club after club, and people would go into one club to watch a set and then go to another club for the next set. Musicians would go out on the street for a smoke or to get some air between shows, and Dan Morgenstern talks about how you could literally just walk up to Charlie Parker and strike up a conversation.

So, 52nd Street was a thriving scene, but by the end of the 1950’s and the beginning of the 1960’s there was a lot of drug activity and prostitution and more police attention, so the clubs start being replaced by strip clubs, and the scene – such that it was – starts to move down to Greenwich Village, where places like the Village Vanguard and Five Spot thrive. The Vanguard was presenting all kinds of jazz, and the Five Spot was mostly bop and post-bop.

JJM The Open Door and Eddie Condon’s were also in the Village…

JG Yes, Eddie Condon’s started off on 52nd Street then moved down to the Village, and they presented more traditional jazz, the New Orleans Dixieland revival.

One of the other things that struck me while I was researching the book was how the evolution of the music and the places in which it was played was influenced by not just the musicians, but also by external events. As an example, at the beginning of World War I the military was concerned about the abundant sin on offer in Storyville, the red-light district in New Orleans, so they closed Storyville down, putting many musicians out of work. Many of them moved north to Chicago, where they could get work due to the wartime economy. External events like Prohibition, World War II, the advent of radio and television, the riots in Harlem, and even the live radio broadcasts from the Cotton Club were all so important in the development of the music.

JJM To that point, the cabaret tax had a major impact on the music because it forced the club owner’s hands in terms of what they could affordably present…

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Thelonious Monk, Howard McGhee, Roy Eldridge, and Teddy Hill, outside Minton’s Playhouse, New York; c. September, 1947

JG Yes. I heard an interview replayed on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross where she interviewed the drummer Max Roach, and he talked a bit about the cabaret tax and what a turning point that was for bebop. Hearing that interview led me to research it, and I found an archived story in the New York Times that describes the tax and how it was forcing clubs to close because they couldn’t increase their prices without losing their audiences.

This tax came about during the 1940’s, when the US government was coming up with new taxes to support the war efforts. They did things like put a tax on rubber for tires and a tax on gasoline, and these rising costs served to negatively impact the touring bands. Someone came up with the idea of putting a 30% tax on venues that have dancing, or where bands have a vocalist. At the time, swing was the dominant music, and every swing band had a vocalist or two and people danced to it. This caused a huge problem, nowhere more so than in New York, where clubs and ballrooms were making their money on big bands like Cab Calloway’s, but who now had to raise their prices 30%. People may have been doing a little better financially because of the wartime jobs, but not to the point that they are willing to pay that extra 30%. On top of this, music from these venues was staring to be broadcast on the radio, so people were able to get it for free.

So, business starts tanking almost immediately in these clubs and ballrooms. Meanwhile, completely unrelated to this, bebop is starting to take form in venues like Minton’s and Monroe’s, and musicians are breaking free from the strict, regimented arrangements the swing orchestras were playing. Since bebop is music for listening to, there was no dancing or vocalists, which meant that clubs on 52nd Street presenting bebop didn’t have to pay the 30% cabaret tax. Plus, there are only about five guys in a band playing bebop, so clubs were able to better afford the talent. This supercharges bop – it had the effect of pouring gasoline on the fire of bebop.

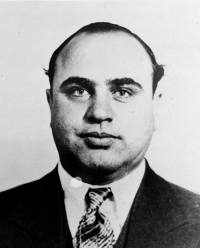

JJM Another thing about these clubs is that organized crime members were often club owners or managers. Al Capone, for example, controlled several venues in Chicago. It was interesting to read about how he insisted on booking Black musicians in his clubs…

Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 3.0

A 1931 photograph of Al Capone made by the US Dept of Justice

JG Sonny Rollins told me about how the bassist Milt Hinton worked for Al Capone, who thought he was a good guy and supported jazz and Black musicians. Other resources I read talked about how Capone felt that Blacks were being oppressed just like his Italian American family. He liked the music a lot personally, and being the biggest bootlegger in the country and basically owning Chicago, he put out an edict that his clubs will only hire these Black musicians. There is a story in the book about how Fats Waller gets kidnapped by gangsters and is taken to a club and told to play. Waller doesn’t know what’s going on, and it turns out that it’s a birthday party for Al Capone. He plays at the party for three days, and people were stuffing money into his pockets and he is having a good old time. At the end of the three days he has thousands of dollars, so what started out as a nightmare turned into a positive thing.

JJM Morris Levy owned Birdland, and Owney Madden owned the Cotton Club. These are serious gangsters…

JG Owney Madden was a guy just looking to make money, period. Morris Levy, who I actually met once, was deeply into this music and was friends with Count Basie and a real advocate for civil rights. So, while there are many negative things one could say about Morris Levy, he was into it for the music, he treated the musicians right, paid them well, and made sure nobody was discriminated against in his clubs. It is much more complex and nuanced than I initially thought.

JJM What were some of the after-hours clubs known for being hangouts for musicians?

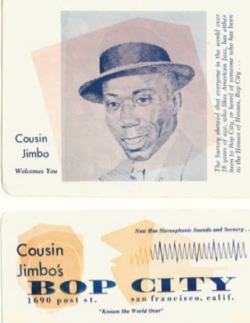

The front and back of a Bop City promotional flyer, date unknown

JG A lot of these clubs were open all night. In Harlem, Connie’s Inn and Small’s were hotbeds. Jimbo’s Bop City in San Francisco opened at 2:00 AM and had non-stop jam sessions. Musicians would finish their paid gigs and then go to Jimbo’s to hang out with their friends and jam. Jack Kerouac and Clint Eastwood used to go there, and it was a very fertile after-hours scene. One of the things that happened was that the wartime economy created demand for war munitions, cars and trucks, so factories were running 24 hours a day. Many of the clubs stayed open for 24 hours and would have breakfast shows for the shift that just got off work. A lot of jamming happened in those clubs because they were open for musicians to blow off steam after maybe playing their more polite set in a hotel ballroom.

JJM In addition to New York, your book looks at clubs in cities like Atlantic City, Chicago, Kansas City, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Los Angeles and San Francisco. What did you learn about the club scenes in cites other than New York?

JG They all had sort of micro-climates for jazz. Typically, what I’d find is that because of racial segregation and redlining, in almost every city African Americans were forced to live in certain areas, and those neighborhoods tended to have businesses that catered to them, and in most cases that meant that they had jazz clubs. These clubs were a big reason why white people would come into an African American community.

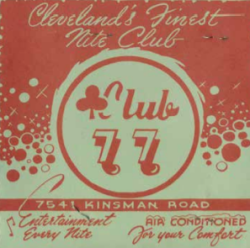

Photo folder from Cleveland’s Club 77

.

Louis Jordan at Club 77, date unknown

Some scenes were easier to research than others; in some cases there was next to no information on the jazz clubs in these cities. Because New York was the epicenter of this it was easier to research it – I could talk to Dan and Sonny and Quincy, all of whom lived in New York at the time, and really find out a lot. But when researching Cleveland, for example, there was only one expert I could find who knew the history of the Cleveland jazz scene, Joe Mosbrook, who literally wrote the book on the subject.

This is a crazy story. My friend Howard Kramer, the former chief curator at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, had given me scans of a souvenir photo folder he had from the Cleveland club Club 77, inside of which was a picture of Louis Jordan performing at the club. I tried and tried, but I couldn’t find any information about Club 77. Finally I wrote to Howard and asked if might know anyone in Cleveland who knew something about the club. He told me he’d ask his next-door neighbor, who turned out to be Joe Mosbrook! Howard shared with me what Joe knew – which was almost nothing – some of these clubs were only open for two or three years in the 1940’s, and the only information he could find was by researching advertisements in African American newspapers archived on microfilm. So, literally the only thing I could find about some of the clubs in Cleveland was via Joe going to the library, scanning newspaper ads on microfilm, and teasing out whatever information he could. My editor was constantly urging me to find more information about some of these clubs, but here was the leading authority on Cleveland jazz clubs, and all he could give me was an approximate timeframe and a short list of artists who had performed there. It wasn’t like The Cleveland Plain Dealer was out there interviewing the owners of a Black jazz club that was only in business for three years.

And it gets weirder. I sent an advance copy of the book to the musician Joe Lovano. He was very impressed that I’d written about his hometown, Cleveland, but noted the “Jerry Lovano” mentioned as having played at Club 77 was actually his father, Tony Lovano. Evidently his father’s name was listed incorrectly in the original ad.

JJM When you interviewed Jason Moran about the collection, how did he react to it and to your book project?

JG In addition to doing interviews with people who were at the clubs – Quincy, Sonny and Dan – I wanted to talk to a younger musician who has an eye on history to get his take on these images, and to get a kind of kaleidoscopic look at these clubs. A close friend of mine introduced me to Jason – who is the head of jazz programming at the Kennedy Center – and he agreed to do the interview, which we did at my friend’s house. As I was pulling out the souvenir photos, he said he had literally never seen any anything like these, ever. It blew his mind. He told me that he was always documenting everything regarding his career, but it never occurred to him to photograph an audience, and he didn’t remember ever seeing pictures of a jazz audience until these photos. All the other interviews were done over the telephone, but I was able to bring all this stuff for him to look at, and he was just blown away. It was almost as if he were sitting there slack-jawed.

The 1932 Cotton Club Parade featured songs by legendary composer Harold Arlen and lyricist Ted Koehler, including the standard “I’ve Got the World on a String,” written especially for the revue

.

Photo folder from the Cotton Club’s midtown location, late 1930’s

He had many outstanding insights, including one about the Cotton Club, where Sonny had said Black musicians were hired just so the white owners could make a buck, and Dan said that after talking to a lot of Ellington band members, they thought playing there was a good gig, that you had to take the “good with the bad.” Jason noted that Black people had been so oppressed in the United States that musicians were just looking for any opportunity to play their music and be able to express themselves and have their music heard. Through that lens, he understood that a gig at the Cotton Club was important because musicians got to do their thing there, and while he understood what Sonny was saying, these clubs were providing musicians with an important opportunity to express themselves, to get positive feedback, and be paid well. Jason was very deep and thoughtful.

JJM What do you hope that readers will take away from the experience of reading your book?

JG Many people have been surprised at the racial component and how jazz clubs were mostly integrated, and others have been taken in by the sheer joy on the faces of these people at these clubs, the musicians who played in them, and the history of the clubs. It was important for me, while the collection was still in my possession, to put all this down in an easy to digest, attractive format that allows people’s imagination to run free, and hopefully readers will discover an interesting new angle with which to look at social history, racism, music history, cultural history, and fashion.

.

___

.

Charlie Parker poses with fans at Café Society’s Fifty-Eighth Street location, date unknown

.

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

An integrated audience at the Downbeat Club, New York City, c. 1948

.

.

___

.

.

Listen to a remastered recording of Dizzy Gillespie playing “52nd Street Theme” (1948), with Don Byas (tenor sax); Milt Jackson (vibraphone); Al Haig (piano); Bill DeArango (guitar); Ray Brown (bass); and J.C. Heard (drums)

.

.

___

.

.

Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s

by Jeff Gold

.

.

“A great book…A story that needs to be told!”

– Sonny Rollins

.

“The images testify not just to jazz’s popular peak but to a now-distant optimistic moment of promise in American life…These images bequeath a rarely published view of Black American middle-class life at mid-century: relaxed, elegant, and urbane…You also come away struck by how singular this postwar moment was. Finally, though, you come away refreshed by the spirit of what once was, a spirit that rebukes and shames where we seem to be today.”

– The New York Review of Books

.

“…offers an unprecedented look inside the jazz clubs from this era across the United States. Drawing on an incredible trove of never-before-seen photos and memorabilia, [Gold] gives us a glimpse at a world that was rich in culture, music, dining, fashion, and more.”

– LA Weekly

.

.

___

.

.

Jeff Gold is a Grammy Award-winning music historian, archivist, author, and executive. Profiled by Rolling Stone as one of five “top collectors of high-end music memorabilia,” he is an internationally recognized expert who has consulted for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Museum of Pop Culture, and various record labels and cultural institutions. He has also appeared as a music memorabilia expert on PBS’s History Detectives and VH1’s Rock Collectors. His other books include 101 Essential Rock Records: The Golden Age of Vinyl from the Beatles to the Sex Pistols and Total Chaos: The Story of the Stooges/As Told by Iggy Pop. He own the music memorabilia website Recordmecca.com and writes about topics of interest to collectors on its blog.

Follow Jeff on Twitter at @recordmecca or on Instagram at @recordmecca.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on February 26, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

Unless otherwise noted, all images © Jeff Gold, and are published with his consent

.

.

.