.

.

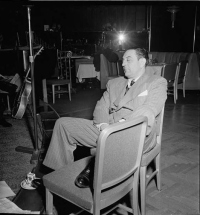

William Gottlieb, c. 1940

.

.

___

.

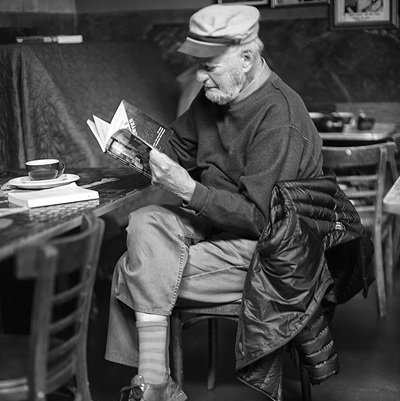

…..The first interview I ever hosted for .Jerry Jazz Musician was in 1997 with William Gottlieb, best known as a jazz photographer but who only came into that field when the Washington Post — for whom he wrote a jazz column — determined they could no longer pay for a photographer to accompany his column. At that time, Gottlieb purchased a camera and took pictures, mostly of musicians performing within the nightclubs of New York.

…..Our telephone conversation about his career – now 22 years in the past – remains memorable, as was my subsequent visit to his film studio in New York. He was a sincere gentleman with so much to share, as is apparent in the interview, which is published on this page in its entirety.

…..When this interview took place, Gottlieb – who passed away in 2006 – was in the midst of promoting his book of classic images,.The Golden Age of Jazz.

…..In line with Gottlieb’s wishes, in 1995 his photographs were sold to the Library of Congress. Selections of his photographs are shown throughout the interview.

…..-Joe Maita, founder and publisher, .Jerry Jazz Musician

.

.

_____

.

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Parker, Tommy Potter, Miles Davis, Duke Jordan, Max Roach. Three Deuces, New York, N.Y., c. August, 1947

.

.

____

.

.

JJM. You attended Lehigh University in the 1930s?

WG. Yes, I graduated in 1938.

JJM. What did you and your folks imagine yourself doing?

WG. I was in the college of business and majored in economics. I was their hot economic student at the time, although I realize I learned very little. Later, I did graduate work at the University of Maryland in

Economics, taught Economics, and actually worked professionally for the U.S. Government as an Economist, but that was a very minor part of my career.

JJM.How did you get into music?

WG. I got sick with trichinosis one summer, and while recuperating at home, my most constant visitor was a fellow that had been my mentor in high school. He was a classical piano player of no merit whatsoever, but a jazz fan. He was very erudite, and subscribed to music magazines not only from the U.S., but also from England and France. It was in the foreign publications that he became aware that jazz was America’s great contribution to the arts.

He became a collector of jazz records. He couldn’t play jazz but he could buy the records and listen to them. When he visited me, he knew that I was the editor of the college newspaper and that I had the privilege of reviewing records. At the time, let’s just say I was a Guy Lombardo fan– who was a great guy and an important fellow. This friend straightened me out though and put me on to Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. By the time I recovered and went back to college, I was a jazz nut.

Guy Lombardo, Starlight Roof, Waldorf-Astoria, New York, N.Y., c. 1947

JJM.Did your parents share your interest in Lombardo?

WG.I don’t think my parents were interested in any popular music, or even classical music. They were not in that groove, especially. Actually, I was an orphan by the time I was 14, so there is a lot about them that I don’t know. Through outside influences I became interested in jazz.

JJM.And you wound up as a journalist…

WG. I was a writer in college, and was feature editor in the campus newspaper, so yes, I was a writer, and to this day I still consider myself a writer. My first job, however, was in advertising, and that was by serendipity. I had an introduction to the business manager of the .Washington Post. This was in the Easter vacation just before graduation, and I had not yet even applied for a job, yet alone had one. I had a protege on the campus magazine whose uncle was the business manager of the .Post. At the time I was on the Lehigh tennis team and we always traveled south to schools like Duke and North Carolina State and this nephew suggested I stop in and make some inquiries at the .Post. I knew that we’d be passing through Washington on Saturday, because that morning we were scheduled to play against Johns Hopkins but I figured there wouldn’t be time to get to visit anyone in Washington and that. Anyhow, I doubted that someone as high up as the business manager of the .Post would be working on a Saturday. However, that proved not to be the case. It turned out that at the .Post, even the executives worked hard! Finally, I doubted that even if he were there that he would have time or the desire to see me.

As a precaution, I took a number of magazines with me that I had edited so that I could use them as a pitch for the job. I also sent to this very fellow that introduced me to jazz, (by this time he was producing plays at American University in Washington) a letter saying that if I had time I would pick up a girlfriend of mine in Baltimore (now my wife of 58 years), and we would stop and look at his show. And if the tennis match would be rained out, I would stop to visit the business manager of the .Post.

Sure enough, it rained, and while I parked my car outside the .Post building, with my wife-to-be in it, I went up and saw the business manager and told him I wanted to be a writer on the .Post. He introduced me to the managing editor, who much to my astonishment and great delight hired me. When I went back to the business manager and reported that, he said “Listen, why not come work for me instead, because in the long run you will make more money in advertising.” Our personalities meshed, and he proved to be a delightful man who lived into his 90’s. At any rate, I went to work with him, but it turned out I disliked advertising. So to get back to writing, and to spread the gospel of jazz, I went back to the managing editor, and asked that in addition to my advertising duties, would he let me write a weekly jazz column?

JJM.Were the events you reviewed confined mostly to the Washington metro area?

WG. Partly. I also got records to review from record companies all over, so to that extent it went beyond Washington.

JJM.How did you get into photography?

WG. I asked the managing editor if he would assign a photographer to go around the clubs with me, and he said he will give it a trial run. But after two weeks, he said it was too expensive, so he stopped my having the privilege of the photographer. I was so determined though to have these events photographed. This was the time when .Life magazine was the focus of all aspiring journalists, so I went out and at my own expense bought a Speed Graphic, that big, expensive, complicated camera that press photographers used in those days, and with a little help from the staff at the .Post I learned to use it. From that point on I became a writer/photographer. I quit my advertising job and went back to college at the University of Maryland and taught Economics.

Later, when war became imminent, I became an Economist at the Food and Price Administration, which was the organization that set prices during war time. Then the army got me, and because of my background, I was able to become a photo officer in the Army Air Corps. After four years in service I got out and very promptly got a job as an assistant editor with .Downbeat magazine. No one ever paid me for my photos, but it enhanced my columns, I enjoyed it, and it was easy compared to writing.

JJM. Was this simultaneous to the time you had a show on NBC radio?

WG. Yes. I had a weekly Saturday show on the NBC outlet, WRC. I also had a three-times-a-week show on a local station — I was sort of the “Mr. Jazz” of Washington during that period, and I was only about 22 years old. Then the Army put its hooks into me and I had to give up all of that. When I got out of the service, I went to New York, and the people at .Downbeat knew of me because of the reputation I built up in Washington, so I got a job rather quickly. I was there for two-and-a-half years, and by that time, for a variety of reasons, I got out of jazz completely. I then established a business producing educational film strips and other educational material.

JJM.This was 1948 or so?

WG. Yes. I quit cold turkey.

JJM.So, you were in the business of jazz from 1938 to 1948?

WG. Yes, except for the four-and-a-half years I spent in the Army, so it was actually a very small window when I was involved primarily in jazz.

JJM. To many of us too young to have lived during that era, your photographs are fascinating and spark curiosity about “Golden Age of Jazz.” What event initiated the “Golden Age of Jazz?”

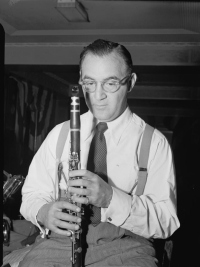

Benny Goodman, 400 Restaurant, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1946

WG. You can pinpoint certain specifics but that in itself would not explain this huge interest. When Benny Goodman made his cross country tour in 1935, it was rather unsuccessful until he hit California, where he played before a crowd who had been listening to his radio broadcasts while the rest of the country hadn’t because the hours were awkward. His music was broadcast live, and by the time it came on the radio, the only people still up were those on the west coast.

Almost overnight, there was a jazz craze, and it became the most popular music of the time, a status that it no longer has, even though there has been a resurgence in jazz, especially in its intellectual aspects — books, magazines, festivals, etc. It’s bigger now than ten years ago, but not nearly as big as it was in the late 1930’s and after the war. Then, Goodman and Artie Shaw and performers like that were the most popular people in music, and today its rock ‘n’ roll, country and so on.

JJM.You put the bands of Bob Crosby and Count Basie together for an after hours jam session. How did that come about? What are your memories of that night?

WG. I sure do have memories of that night! First of all, I had given a great deal of attention to the black theater in Washington, the Howard Theatre. All the great black orchestras and movies played there. The Earle Theatre downtown was a white bastion and they had white orchestras. Simultaneously and by coincidence, the Count Basie orchestra was playing at the Howard, and the Bob Crosby orchestra was playing at the Earle. Crosby played a sort of Dixieland, and its members were not only all white, but most were southerners. As I said, I was “Mr. Jazz” at the time and I had the backing of the Washington Post so I had considerable amount of prestige and muscle and nerve to approach both Crosby and Basie.

First, though, I went to the manager of the Howard because he owed me. Prior to my entering the scene, the activities at the Howard Theatre were seldom mentioned in white newspapers, but I featured them not because they were black but because that is where the big jazz was coming from. He was very anxious to return the privilege and when I asked if I could have the use of the Howard Theatre after hours one night to have a private jam session, he said “sure.” I then convinced Count Basie to show up with some of his key men, and more surprisingly, I convinced Bob Crosby to send his key men up to the Howard, which I learned 15 – 20 years later was an uncomfortable mission for the members of the Crosby orchestra. But they showed up, and I had someone record it, the brother of silent movie star Milton Sills. His big passion was making recordings, and he had a very big, heavy, expensive recording machine. He brought that along and we had this private dance session with an audience of only a dozen people, including the sons of the Turkish ambassador, Ahmet and Neshui Ertegun, who became the founders of Atlantic Records. I still see Ahmet. At any rate, we got photos of the event, and one or two appear in the book.

I carried that recording with me for years, but it finally dawned on me that it was an extremely valuable piece of property. When I went to listen to it, it was in a dozen pieces. The recording was a transcript that was 16 inches in diameter, and had a glass vase covered by acetate– these were not pressings, these were cut on that recording machine. A stylus cut into the acetate, but underneath the core was glass, and by the time it dawned on me I should do something with it, the recording was hopelessly shattered.

JJM. This was around the time there were other battles of swing bands…

WG. Yes. I was the Master of Ceremonies for a couple of them, and there is a photo in the book of me with Gene Krupa and Jimmie Lunceford during a competition between their bands.

JJM.Were these planned events?

WG. Yes.

JJM It sounds as though they were the sort of events that inspired camaraderie among the leaders and players of the orchestras. Did that seem to go on?

WG. Yes. It went on in certain locations on a semi-permanent basis up at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem for long periods, and there would be battles of swing all the time.

Jimmie Lunceford, William Gottlieb, and Gene Krupa, c. 1940

JJM.Who judged the competitions?

WG. In the couple in which I presided, they had all kinds of dance competitions, and they were judged by applause from the audience. In the case of Lunceford and Krupa, Lunceford won. He had an overwhelming, powerhouse orchestra, and furthermore, the audience was largely black.

JJM.Segregated audiences must have been typical in Washington at the time…

WG. Washington was a southern town at that time, before the war. Because of my special position in jazz, and because of my personal inclinations, I had many black friends, but because it was such a southern place, the only place we could meet together was in our respective homes, with one exception, the Union Station (train station) restaurant. That was the only restaurant in Washington that would permit blacks and whites to eat together.

JJM. In your book you described how Frank Sinatra had a negative effect on jazz because he brought about a decline in the big bands…

WG.I consider Sinatra to be possibly the best singer that America has ever produced. He had a way of handling his delivery, the microphone, so that everyone in the audience would feel that he was singing just to him or her. He always had an underlying jazz beat, but a lot of people object to me even including him among the jazz people.

JJM. He took the focus away from the band leader…

WG.Yes. Where he had a negative effect was in that by 1948 or 1949, there was a recession going on and the band business was in decline. A lot of the bands had blown up in size to 19 pieces; big payroll, and they began to fail. About that time the singers, notably Sinatra, became dominant. In prior years, the singer was the adjunct to the orchestra, but the singers became so big it got reversed, and that was certainly true with Sinatra. The attention was switched over to the singer and the orchestra was less important.

JJM. In essence the ensembles were forced to shrink because the orchestras couldn’t bring in the money to pay for 19 musicians…

WG. Yes. Thats right. It got to the point where the singers almost didn’t need an orchestra. They could get any four or five guys and they had a show.

JJM. Lets talk about 52nd Street. When you think about 52nd St, it has the same sort of appeal to a fan of jazz historically as, say, Ebbetts Field does to a fan of baseball. It was so rich and alive…

52nd Street, New York, N.Y., c. July, 1948

WG. Yes, but it was even bigger than the Ebbets Field example — 52nd Street was the center of the jazz world. One block had four or five very important jazz clubs, and a couple more just a block or so away. And you could go there and for 50 cents get a beer or soda and stay at the bar as long as you wanted and listen to great performers like DIzzy Gillespie for half-a-buck. Then you could go next door and listen to someone like Art Tatum and listen to him for a while for another half-a-buck or a buck. It was a paradise, and some of the clubs specialized in Dixieland and others in period jazz, and still others that were the centers for bop music, and those ultimately dominated the street.

JJM. How did this evolve? What was the first club?

WG. First club was the Onyx Club, and that was on the south side of the street, and later it moved to the north side of the street. Carl Kress, a distinguished jazz guitarist, was a partial owner of the Onyx, and it stayed on for a good while before others came along.

JJM. So the Onyx had quite a bit of success, and other entrepreneurs in the area decided to open competing clubs…

WG. Yes. You could see 10 to 20 performances in one night!

JJM.Of all the performances you saw on 52nd Street, what was the one that sticks out in your mind?

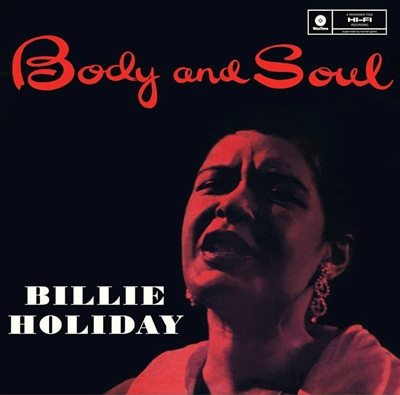

WG. I have two. One is when I covered Billie Holiday after she had gone into decline. It was predicted that she wouldn’t show up and when I went to cover it at the opening time she was no where to be seen. Playing a hunch I went backstage, and there she was, half dazed on a bed. I helped her get dressed and out to the microphone. But she looked so bad and sang so poorly I didn’t have the stomach to continue on, so I took no pictures of her. I wish I had, but I didn’t.

JJM. Was she just out of prison at this point?

WG. No. When she came out of prison, she was in great shape and she was most beautiful. She had gone almost a year without any drugs or alcohol. No, this was somewhat after that, when she began to degenerate. When she got out of prison, and I spent several sessions with her, she was at her peak.

JJM. What was the other memorable performance?

WG. I went in to listen to Dizzy Gillespie’s big band that was crowded into one of those small clubs and sure enough, Ella Fitzgerald, whose boyfriend and future husband Ray Brown played bass in Gillespie’s band, showed up. Everyone asked Ella to sing, and, to give support to Ray Brown, she obliged and sang. She had a very colorful “Dizzy” hat on, and I happened to have my camera with me, so I jockeyed my camera into position. I beckoned to Dizzy, with whom I had a marvelous rapport–very intelligent and perceptive, and despite his Dizzy antics was a very dependable guy–he understood what I wanted. He moved into position so I could include him in the photo and I got what proved to be a very memorable photograph of Ella and Ray.

JJM. Who made up the audience?

WG. By then, it was after the war, and it was New York City, so it was integrated.

JJM. What about in Harlem?

WG. Not as much. Since most of the music had moved to 52nd street and Greenwich Village, it wasn’t like the earlier days where if you wanted to hear good jazz it was played up in Harlem and you had to go up there.

JJM. What sort of after hours scene existed for the musicians? Did they retire to someone’s house? Did they play some more?

WG.Yes. All of those things. The most important place proved to be a Harlem night club called Minton’s Playhouse. It was there, really, that bop music was formulated and created. The sparkplug there was the house pianist, Thelonious Monk, and later, after he was no longer there, I took him back there…

JJM. Nobody could find him, right?

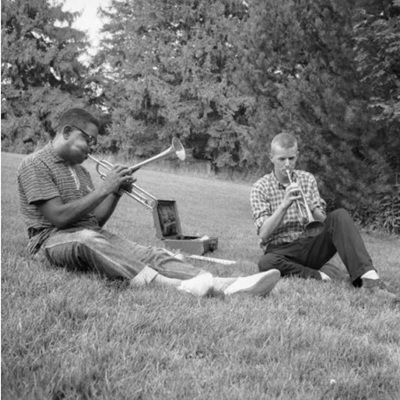

Thelonious Monk, Howard McGhee, Roy Eldridge, and Teddy Hill, Minton’s Playhouse, New York, N.Y., c. 1947

WG.That’s right! He had disappeared for about 10 months, and I made it a personal project to try to locate him. His mother hadn’t seen him in six months, and the last manager of the place where he had worked said he went out for a smoke and ten months later he still hadn’t come back. Mary Lou Williams, who was the leading female jazz musician of the time, heard I was looking for Thelonious and said she could get him, which she did. He came to my Rockefeller Center office, but he was very uncomfortable in those surroundings so we got into a cab and went to Minton’s Playhouse, and by a great bit of good fortune, hanging around in front and in midday, there was Howard Mcghee, at the time second only to Dizzy in stature as a trumpeter, Roy Eldridge and Teddy Hill, who had been an orchestra leader, but was now manager of Minton’s. I photographed the group under the marquee of Minton’s, and that has become something of a classic. I took him inside to the piano he presided over earlier at the club, and photographed him at the piano.

JJM.How was that reported at the time? The fact that Monk was missing for an extended period must have caused some stirrings within the jazz community about his whereabouts, and when he arrived was there some sort of reporting about his reappearance?

WG.No. I could never get on to anything tangible, but later at one of the exhibitions I had at a museum down south, a man came to me that seemed to know what he was talking about. He said that Monk spent those ten months just relaxing and experimenting in an apartment of a woman of Danish royalty [Pannonica Rothschild de Koenigswarter] who favored bop musicians. She had a big sound proof apartment, and he spent the time there. It may have been the same apartment in which Charlie Parker died.

JJM.What factors emerged at that time to contribute to the demise of 52nd street?

WG.There were several things. First of all there was a general recession and a lot of bands folded. Then, there was the rise of bop music. Bop has a huge audience today, but back then, it was very upsetting to the audience of jazz fans that then existed. They found bop very unappetizing.

JJM.Bop was viewed as too rebellious…

WG. It’s a strange sound. To people that were accustomed to Count Basie’s orchestra, or the earlier Dixieland groups and so on, to get this rapid fire, often loud music was strange; they didn’t like it. The older musicians didn’t like it. They found it very difficult to play, and it didn’t make sense to them. So that alienation brought about by the rise of bop helped to undermine the influence of 52nd street.

JJM.Any other factors?

WG. Yes, finally, 52nd street was absorbed by Rockefeller Center and its surroundings. It was good commercial real estate, and jazz clubs in ground floors or basements of these brownstone homes were torn down and skyscrapers were put up in their place.

JJM. Regarding your statement about how the older musicians didn’t like bop, the originators of bop were viewed as men whose intent was to turn the old way upside down…

WG. An artist can’t extend his career and ability by simply playing in the same groove. You have to establish new rules, new games. Sometimes you go backwards, sometimes forward. The sons of Johann Sebastian Bach thought that Papa was pretty good, but they would show how to really write music. They were really very good, but two centuries later you hardly know of them, but you still know of Papa. Just because its new, doesn’t make it better. Bop was new, but not necessarily better.

JJM.When bop started, many of the white musicians like Stan Kenton and Woody Herman went into the direction of “progressive” jazz…

WG.Yes, the Kenton type of music was a kind of reaction against traditional jazz, just as bop was. Kenton was very ambitious and driven. He wanted to make his jazz the jazz of the future, and he worked very hard to that end, but mostly unsuccessfully. The bop tradition predominated and even now some progressive jazz is considered a little dated even by more contemporary jazz people. I am not too familiar with the post-boppers because I was out of this field, until very recently when I began restoring my old photographs. I missed out on getting an understanding of the people in jazz after Miles Davis.

JJM.Bandleaders like Kenton and Herman led a different lifestyle than the bop musicians. They were out on the road while the bop players spent most of their time in the clubs of New York…

WG.Yes, because the Kenton and Herman people were able to hold on to their large personnel format and travel, whereas the boppers were mostly very small groups and they weren’t marketable entities for these road trips.

JJM.Did you know (fellow jazz photographer) Herman Leonard?

WG.Yes, he and (fellow photographer) Bill Claxton and I are going to have a show together in Berlin in October. We are all fans of each other.

JJM.Was Leonard influenced by your work?

WG.He says he was. I am somewhat a Granddaddy of the whole bunch. I am 80, and none of the other guys are near that.

Dizzy Gillespie on 52nd Street, New York, N.Y., c. 1946

JJM.Was there a particular musician that really liked being photographed?

WG.Dizzy Gillespie was a very likable, cooperative, bright, intelligent guy, and he always contributed whenever I was shooting him.

Willie “The Lion” Smith was really unique, a very colorful guy. I had a lot of interesting experiences with him. I was talking to someone the other day about a cab ride I had with him to the Howard Theatre. I got out of the cab early, but I could see that the cab driver was saying “Hey, how about the fare?” Willie looked at him and said “The Lion does not pay for taxis.” He left and the cab driver was so stunned that he didn’t do a thing.

JJM.Who struck awe in other musicians?

WG.Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, the two greatest figures in jazz. I had opportunities to get to know them moderately well. I don’t pretend that I was buddies with them, but I knew them and they knew me. They’re awesome, larger than life, super geniuses who revolutionized the music form, each in their own way. Jazz was never the same after Louis Armstrong made himself known, and Ellington was a creative genius.

JJM.Benny Goodman had quite a reputation…

WG. Goodman had more impact than any of them in making jazz famous and popular. He was also known quite properly as a very difficult, unlovable character, but you had to regard him as the giant as he was.

JJM.Who was the most influential “behind the scenes” person you encountered, whether it be a writer, critic, or manager?

WG.John Hammond, perhaps, who put his finger on all sorts of people, from Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, up to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. He helped discover them and helped popularize them.

JJM.Did any of the musicians you photographed have an appreciation for your work?

WG. I learned from the beginning not to even show them the photos. They would see them in publications. If they chose to say anything, fine, but they usually didn’t.

JJM.So, they never came to you and said,”Bill I would like to see the photograph you took of me and Ella last night?”

WG.No. The very first assignment I had with .Downbeat was to cover the Ray McKinley Orchestra at the Hotel Pennsylvania, which had been the Glenn Miller Orchestra. Miller was killed during the war, so Ray, the drummer and sometimes singer, took over the leadership. I didn’t think the orchestra was very good.

He was playing in front of a black background. I couldn’t get a grip on his personality so I didn’t quite know how to photograph him, so I resorted to a gimmick. Because of the black background, if I could keep the camera steady by placing it on a table, I could make multiple exposures of him to create the idea of motion for a drummer. Much to my delight, it ran as a cover story of .Downbeat. I said “Wow, that’s great!” I went back to him after the magazine came out and I thought he would pat me on the back and hug me or something,but he didn’t say a thing. He was cold and stiff. I resolved then never to show my results to a musician. If they wanted to comment, fine.

Forty years later, I was at a jazz festival at a hotel, and sure enough sitting at the same table with me was Ray McKinley. I asked him what kind of reactions he got from that double exposure that was used as a cover shot on .Downbeat. He said “What double exposure shot?” So, I went up to my room in the hotel and got a copy of my book and I brought it down and showed it to him and I said, “That’s the shot I meant.” He said, “Did you take that?” I told him I did and he said, “I’ve seen it hundreds of times! God bless you!” So it took me 40 years to get a reaction from this guy.

JJM.What photo are you especially proud of? Is there a photo you are personally enjoy the most?

WG.Well, that shot of Billie Holiday that shows the anguish in her voice has become the most widely reprinted photograph of a jazz person. Quite apart and different from that is the picture I took of the drummer Dave Tough. Very few people pay attention to it, but discerning people like Whitney Balliett of the New Yorker and the Ahmet Ertugen of Atlantic think it’s possibly the greatest jazz photograph ever taken.

.

.

_____

.

.

Click here for access to Gottlieb’s collection at the Library of Congress

.

.

.

What a terrific interview! I love Mr. Gottlieb’s jazz photos. I had the chance to email him a few times when I was thinking about buying a print of one of his photos. We shared the same birthday and when I mentioned that I played tennis, he was off and running..lol. I think this was in the early 2000’s and I’ve long since lost the emails. He came across as a genuinely nice man and it was a thrill for me to “talk” with him. He made so many iconic photos..and I think he was touched when I mentioned that he brought an era back to life for me and others.