.

.

photo by Erinn Hartmann

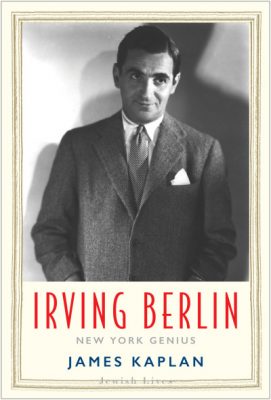

James Kaplan, author of Irving Berlin: New York Genius

.

___

.

…..Irving Berlin will forever be known as the greatest songwriter of the golden age of the American popular song; George Gershwin, and others, have called him that. During a career that began in the era of ragtime and ended at the height of rock and roll, Berlin composed 1,500 tunes, among them are three of the most popular of all time – “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” God Bless America,” and “White Christmas.”

…..As with his music, Berlin’s story as a self-made man whose brilliant career began as a singing waiter has endured for generations, and acclaimed author James Kaplan has taken it up in a hearty and sophisticated new biography,.Irving Berlin: New York Genius.

…..In a February 7, 2020 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Kaplan talks about Berlin’s unparalleled musical career and business success, his intense sense of family and patriotism during a complex and evolving time, and the artist’s permanent cultural significance.

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

NBC Radio-photo by Ray Lee Jackson / Public domain.

Irving Berlin, 1937

.

.

“Berlin has no place in American music, he is American music.”

– Jerome Kern

.

.

.

Listen to a 1935 recording of Fred Astaire singing Irving Berlin’s “Cheek to Cheek”

.

___

.

JJM You have written what many call the definitive biography of Frank Sinatra, as well as major profiles of people like Miles Davis, Meryl Streep, Arthur Miller and Larry David. What inspired you to write a biography of Irving Berlin?

JK That would go back to the musical roots of my family of origin. My mother was a Manhattanite who in the late 1940s attended what was then called the High School of Music and Art, which is today the High School of Performing Arts. She was a singer and a pianist, and she and my father both loved the Great American Songbook and Broadway musicals, so recordings of this music were frequently playing. And, my mother played and sang and Berlin was one of her favorites. So all this was in my ears as I was growing up.

I was of the generation that instantly fell in love with the Beatles the second they showed up, and rock and roll took me over in the 1960s – and I love it to this day – but it took me awhile to admit to my ears all the other great bodies of music that I appreciate so much today. So, that’s a complicated way of saying that I heard Berlin early on in my childhood, but I really only came to appreciate him as a genius when I was in my early 20s, and sort of by accident.

JJM You and I were of the generation that listened to the music of bands like the Beatles, Stones, and Creedence, while our parents were listening to the likes of Ethel Merman, Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney singing Irving Berlin. I remember feeling that since our parents listened to it, it must be completely “square.”

JK Sure, and that’s an adolescent attitude, and the deeper you go into music the more you find that, as Alban Berg himself once said, “music is music.” It is all one great, gigantic playing field, and what is great holds up, and what isn’t disappears.

JJM You wrote, “Even barely into his teens he felt a fascination for what a song said and how it said it. How it was put together, where the rhymes fell.” What was his childhood exposure to music?

JK His family came over from Russia in 1893, part of the great Jewish immigration from Russia and Eastern Europe. He grew up on the Lower East Side, their family dirt poor, and they remained so as long as Izzy Baline– which was his name until he changed it – lived with his family, which wasn’t that long. They were very poor, but the streets of the Lower East Side of New York were filled with all kinds of music. Everybody at that time owned pianos. There were pianos in stores, there were organ grinders on the streets, there were buskers – music was everywhere.

Izzy Baline’s father died when he was 13, and it is inconceivable to anyone who is a parent today, but, feeling that there were too many mouths to feed in his family, he left home at the age of 14 and went out to live on the streets, and very quickly found a job as a singing waiter. He busked first, singing on the street himself. He couldn’t make much money doing that, but as a singing waiter he was very successful, and very quickly found that he could make an awful lot of money from the intoxicated patrons at the bar where he worked by giving popular songs of the day new, dirty lyrics. So he paid attention to lyrics, he paid attention to melody, and he was funny – he was just a firecracker from the word “go,” full of energy, spirit and humor.

JJM You wrote that the patrons of these establishments “dispensed their tips by tossing coins on the floor, partly, one guesses, for the sadistic pleasure of watching the waiters scurry for them.” The volume of tips actually served as instant feedback for Berlin to understand which songs were successful…

JK Yes…He could see what sold. It was a very early education, and he didn’t know it then when he was 15, 16 years old, but he was being educated to become a songwriter.

JJM He was challenged to be a songwriter…

JK Yes, he was specifically challenged. He worked at a bar called the Pelham Café which was run by a man named Mike Salter, who was a fellow Jew. Salter had tight kinky hair and a broad nose and the Neanderthal ethnic habits of the day gave a nickname to the bar – they called it “N—– Mikes.” They didn’t use the euphemism in those days, and weirdly enough, that was not a put down, that was a compliment. It was supposed to be descriptive of a Jew who looked like an African-American, and I think it was seen as a compliment in that, in the context of that era, it had macho overtones. So maybe the best way to put it is that it was a double edged compliment for that time and place.

Salter found out that one of the waiters at Callahan’s, a bar a couple doors away, had written an Italian ethnic song called “My Mariucci Take a Steamboat” in a Chico Marx-style Italian dialect. The song got published and actually sold enough sheet music to make the writer of the song some money. So Salter told the young Izzy Baline, “Since you’re so smart and so clever, why don’t you write a song?” Izzy took it as a challenge, and, together with the piano player at the Pelham Café co-wrote his first song, “Marie From Sunny Italy.” The year was 1907, and Izzy was all of nineteen years old.

JJM Was the song successful?

JK It was pretty successful and it made a few dollars. The incredible thing is that it got done at all, because clever Izzy – who could improvise dirty lyrics under pressure from intoxicated bar patrons – found that actually writing a song was really hard. The piano player at the bar wrote the tune, Izzy wrote the lyrics, a music publisher put out the sheet music, and it sold a few copies and made a few dollars. There is actually a recording of Irving Berlin singing this song, but the interesting thing was that the cover page of that sheet music listed the Pelham Café’s piano player as the music writer, and the lyric writer as “I. Berlin.” How that happened is a little mysterious. According to some sources it was what some people called Izzy anyway because it was sort of difficult to pronounce “Baline,” so people called him “Berlin.” The “Irving” came a little bit later. This was back in an era when newly arrived Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe considered names like “Irving” and “Milton” and “Seymour,” for example, to be very classy, so a lot of Jewish families named their babies Irving and Milton and Seymour. A lot of men who came over with these very Yiddish or Russian or Polish first names changed their name to these English-sounding first names, and the result is that over the years they came to sound very Jewish to our ears.

1906 publicity photo of Irving Berlin

JJM Berlin worked at the Ted Snyder Company, which was, as you described, “like every other successful publisher on Tin Pan Alley, a mill; a warren of small noisy chambers where not only the house talent but song pluggers and postulant composers pounded out would-be euphonies on battered uprights in cacophonous chorus. It would have taken a powerful imagination, not to mention an ironclad will, to conceive fresh musical ideas under such conditions.” How did working under these circumstances impact his songwriting throughout his career?

JK Right from the start, he was very commercially minded. He saw this place where he was working as a mill, and a mill that had multifarious products, both successful and unsuccessful, as well as middling successful products. He saw what sold and what didn’t. I think he began to realize instinctually that songs that sold had several qualities that very few people actually understood. For example, he understood the quality of simplicity, which was the hardest quality of all – to create anything that has simple power is a matter of spending endless hours honing down what starts out by being messy and overblown and ornate. He also discovered the virtues of repetition and wit in the lyrics.

It is astonishing to think that this is a teenager and then a young man in his early twenties who couldn’t read or write music, but found that there were melodies in his head and began to “write” songs through a musical secretary. Berlin would either tap out a melody one note at a time, or he would hum it while the secretary sat at the piano and harmonized it, turning it into a song. So the circumstances of writing were chaotic, distracting and challenging, but Irving saw that wit and simplicity and repetition in lyrics – repeating to good effect, not to ill effect – were very powerful tools. He learned all those lessons working with Ted Snyder and very soon became a principal in the firm.

.

A musical interlude…A 1911 recording of Billy Murray performing “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”

.

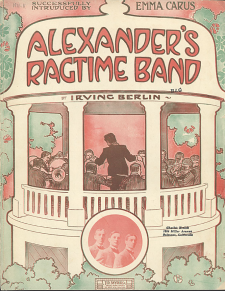

JJM The world fell in love with Berlin because of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” which he wrote while employed by Ted Snyder…

JK Yes, it’s an amazing thing, and I don’t want to barrage you with superlatives, but so much about young Berlin is just astonishing, and to me the astonishing thing about the creation of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” is that here is a 23-year-old who has been working at Snyder’s for a few years and has begun to become successful. He has written some songs, co-written some other songs, and made some money – enough to where he is now able to support his mother, whom he has installed in a nice place in the Bronx. He puts on a necktie and commutes down to Ted Snyder every day to write songs. He is successful enough that at age 23 he can afford to go on a winter vacation down to Florida.

He is about to get on the Miami Limited at Penn Station in Manhattan but has a few hours to kill before train time, so he goes into the office because he has a number that has been lingering in his head for a couple of weeks that he wants to get written down before he forgets it. He goes to one of the musical secretaries sitting at one of the battered upright pianos at Ted Snyder and he hums this tune. The guy starts to play it, and Irving says to him, “Yes, that’s right,” or, “No, that’s wrong.” The secretary has some staff paper and writes down the notes and the chords, and then Irving goes into his office and taps out the lyrics that he has in mind on his typewriter. This all happens in the space of about 18 minutes, unbelievably enough.

He then goes over to Penn Station and gets on the train to Florida and has a nice week there. The song that came to him in those 18 minutes was “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” which, as soon as it was put out in sheet music, and sung and played on the brand new cutting-edge technology of phonograph records, became very swiftly not only a hit in the United States, but traveled across the ocean to Europe and became an international hit. And Irving Berlin at age 23 suddenly found himself internationally famous, and as the sheet music and the records sold, even at a few pennies per copy, a wealthy young man.

1911 sheet music published by Ted Snyder Music Co.

I just want to say one more thing about “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and that is through this new medium of the phonograph record, this bright, jaunty, inventive, exciting, thrilling new song – which, by the way, was not ragtime at all, but rather a march about a ragtime musician – was really the beginning of the American Century, and Irving Berlin was responsible for starting it. The British Empire was in the process of contracting, and the American Empire was starting to grow, and there was Irving Berlin and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” out in the vanguard, in London, in Paris, in Madrid, in Rome – all across Europe this record was being played.

The Hippodrome Theater in London invited Irving to come over and sing his songs in a show called “Hullo Ragtime” and were going to pay him 20,000 pounds, which is the equivalent of about two million dollars today. So Irving sails across the ocean, gets off the boat, takes the train up to London, and then a horse-drawn cab to the Savoy Hotel. When he gets out of the cab, there is a kid on the street selling newspapers while whistling “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

JJM What a great story! Concerning this song, you also wrote that it was “a joyous tribute to African-American musical genius, the first great and lasting one in American popular song, from a Jewish-American musical genius.” How can it get any more American than that?

JK It’s totally American, but this has always been a mixed and nuanced and bittersweet relationship. So many great African-American musicians and composers never got their due, never made the money they should have made – one of the very earliest and greatest being Scott Joplin, who in a sense didn’t invent ragtime, but put it on the map. He was its greatest composer, but died very poor and very bitter.

JJM Berlin wrote this song while he was an employee of Ted Snyder. Because it was such a tremendous success, what kind of complexity did that create for his working relationship there?

JK The long and short of it is that it made him the star. Suddenly Ted Snyder – who is a quite competent songwriter himself – realizes that this kid he had let into the door to be an ornament to his publishing company was actually a genius. That was not an easy thing to find out because it immediately put Ted Snyder second on the bill, and Irving became the first man on the roster, and the Ted Snyder Company became Berlin/Snyder. Very soon after, Berlin went out and started his own music publishing company.

.

A musical interlude…A 1913 recording of Henry Burr singing Irving Berlin’s “When I Lost You”

.

JJM In 1912, his young wife Dorothy died of typhoid after returning from their Cuban honeymoon. Berlin wrote “When I Lost You” in response to her passing, and it became an immediate smash hit. You wrote, “Alec Wilder reminds us ‘none of the one hundred and thirty songs published up to this point in Berlin’s career revealed this aspect of his talent, the ability to write with moving sentiment about personal trouble and pain.’” What did he learn about songwriting as a result of his wife’s passing?

JK I would argue that his wife’s death taught him that he could alchemize loss and sorrow into great music. In this one case he referred directly to his deeply loved deceased wife, but I think all the losses that he suffered – his father’s death when Izzy was 13 years old, Dorothy’s death when Irving was only 24 years old, and then later on in his second marriage the loss of his only son Irving, Jr., who died of crib death on Christmas Day in 1928 – informed his ability to create songs with a crisp edge of emotion without being overly sentimental. While Berlin didn’t address those other losses directly in songs, through this kind of alchemy, as someone who had suffered great loss and knew the dark shadow as well as the sunlight of life, he was able to put both qualities into his most heartfelt ballads. I’m using a lot of words now – as Irving himself did when he wrote four or five drafts of the early version of “When I Lost You” – to try to describe a process that he came upon, which was to create simple lyrics with excess emotion removed, which is so terribly difficult. There are so many overly sentimental songs in the American Songbook, songs that contain bathos instead of pathos, and Berlin was artist enough to recognize that he had to do something different.

JJM Berlin was a songwriter, but he was also a businessman. In 1914 he founded his own music publishing firm, the Irving Berlin Music Company, and later in life he opened the Music Box Theater on West 45th Street, which was the first and only Broadway Theater ever built to accommodate the songs and scores of a single composer. These are only two examples, of course, of his long life in the music business. What kind of a businessman was he?

JK He was a great businessman, and he was a tough businessman. When he started working with Hollywood, for example, Hollywood moguls spoke of Berlin sometimes bitterly, but with a kind of awe. He was a ruthless representative of his own commercial interests who knew what he was worth, and he knew he was worth a lot. He bargained hard every time he got a chance.

JJM The studio head of RKO, Pandro Berman, called Berlin “the toughest trader I’ve ever met in the film business, the hardest-headed businessman I’ve ever known.”

JK Yes, there was a great deal of admiration, and what Pandro Berman got – for a lot of money – was an Irving Berlin who wrote great scores for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, including the greatest musical of the 1930s, Top Hat, and several musicals that followed.

JJM Another thing from that era that is fascinating from a business perspective is that it was the advent of radio, film, records, and eventually television that created new challenges for songwriters regarding copyright…

JK Yes, Berlin was also a co-founder/charter member of ASCAP (Association of Songwriters, Composers and Publishers), and they fought very hard for those rights, even boycotting radio and recording companies at several junctures along the way. So, while Berlin fought for himself, he fought for other songwriters as well.

Irving Berlin, 1918…a sergeant in the United States Army

JJM You wrote, “In 1916 – 17, ragtime suddenly wasn’t everything in America anymore, and the man who had been dubbed the “King of Ragtime” was in danger of becoming irrelevant…Then history (World War I) stepped in to help him out.” Did Berlin see a marketing opportunity in World War I, or did he write music from a sense of patriotism?

JK Berlin was intensely patriotic throughout his life. What he was not, however, was a happy soldier. He applied to become a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1915, and his application was finally approved in 1917, whereupon he was immediately drafted into the US Army. Berlin found himself instantly transferred from the life of a wealthy young bachelor to a private in the Army who had to be awakened every morning by this horrible bugler playing reveille at 5:00 AM, and since Berlin was a lifelong night owl – he worked throughout the night – he didn’t like those hours.

Berlin immediately seized on a commercial opportunity that presented itself when he was a private at Camp Upton out on Long Island, New York. His commanding officer wanted him to write an Army show as a sort of fundraiser to create a recreation center for the soldiers. Berlin, however, had a bigger idea – he wrote an Army show, Yip! Yip! Yaphank!, which he took to Broadway, and that show not only raised a lot of money for the Army, it kept Berlin’s name alive, and also liberated him from having to get up at 5:00 AM. Berlin even wrote a song about that called “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.” But he was always commercially clever, and this was one of his cleverest moves, turning lemons into lemonade – the lemons of being a draftee and a private in an Army camp and having to get up early into becoming the successful writer and producer of a smash Broadway musical.

.

A musical interlude….Ethel Waters sings “Supper Time”

.

JJM In the early 1930s, Berlin found himself in a creative malaise until he wrote As Thousands Cheer in 1933, which marked the first time an African-American woman – Ethel Waters – had ever starred in a Broadway musical. How did this show’s success change Berlin’s life?

JK During this time he went through what he would refer to later in life as his “dry spell.” What I believe is that it was the onset of clinical depression, which actually hospitalized him for a few years after World War II, and this depression was the result of several things. In 1928 his infant son Irving, Jr. died, and soon after that came the Depression, during which Berlin lost all of his money. Fortunately he had a wealthy young wife, and he also had a good way of making money, which was writing songs, but his initial trip to Hollywood – to write the score for the movie Reaching for the Moon in 1930 – was terribly unsuccessful. The movie studio cut all of Berlin’s songs from the movie and turned it from a musical into a straight comedy, and Berlin was very depressed by this.

At about this time a producer put Berlin together with Moss Hart, a brilliant young playwright who had just barged on to the Broadway scene, and in 1931 they began writing their first musical revue together, Face the Music, which did pretty well but the Depression weakened ticket sales. They then wrote a follow-up called As Thousands Cheer, a satirical revue that was a huge success, and this reenergized Berlin.

The brilliant concept of the show was a Broadway musical in the form of a newspaper – the different acts in the revue were the different sections of the newspaper, so there was a front page, a sports section, a society section, a gossip column, and even the weather page. It was all a lot of fun, and the audience was mostly made up of wealthy people having a wonderful time.

The second act opened with a cute little skit about a young society couple waking up in bed together on their wedding day– that was pretty scandalous back then –immediately followed by a curtain coming down, emblazoned with a big, dark headline: “Unknown Negro Lynched by Frenzied Mob.” The effect of this scene on this wealthy audience, which up to then had been having the time of its life laughing at all the funny songs and skits, was electrifying. There was dead silence, open mouths, as they stared at the headline. Ethel Waters then comes out and sings an amazing song that Berlin has written called “Supper Time,” the essence of which is that this woman’s man isn’t coming home for supper because he has been lynched. This is six or seven years before Billie Holiday’s great song “Strange Fruit” on the same theme. Irving Berlin could have very easily just created light, frothy, funny tunes, but he had the creative genius and the social consciousness to write this groundbreaking number.

JJM Yes, and this wasn’t the only time Berlin addressed race issues head on, for example, during his World War II musical revue, This is the Army…

JK Yes, during World War II he wrote another army show called This is the Army, the theme song of which was “This Is the Army, Mister Jones.” What you may be referring to is that This is the Army had an all-Army cast, and Berlin recruited a couple dozen African-American soldiers who also happened to be musical performers, thereby turning the cast of his revue into the first integrated unit in the U.S. Army.

JJM Berlin wrote countless songs, many of which are known to today’s audiences, but it is safe to say that everyone knows two of them, “God Bless America” and “White Christmas.”

JK Absolutely.

JJM “God Bless America” debuted in 1938 but he actually wrote it during World War I…

JK Yes, he wrote it for his World War I Army show, and his musical secretary at the time – a guy named Harry Ruby, who went on to become a successful songwriter himself – told Irving that there were already a lot of patriotic songs around, discouraging him from putting it out at that time. Berlin was always hypersensitive to criticism of any kind – he would wilt at the slightest suggestion that something he had written might not be so great – so he put the number away. The song was “God Bless America.”

Kate Smith, 1934

He didn’t take it out again until 1938, when the manager of a very popular radio singer named Kate Smith asked Berlin if he had any patriotic songs for Smith to sing on her radio show. Berlin found the sheet music for “God Bless America” and changed around a few lyrics that needed to be tidied up and updated a bit, and gave it to Kate Smith. She debuted it on her show in November, 1938, and the song became an instant smash, so popular that a lot of people began to suggest that it replace the “Star Spangled Banner” as the national anthem. Berlin wasn’t having any of that, though – he said we already have a perfectly good national anthem, and we don’t need another.

JJM The song’s huge success created cultural challenges for Berlin, He got a lot of pushback…

JK Yes, he got a lot of pushback. This was 1938 and the war in Europe had begun, and much of Europe found itself threatened by this gigantic German war machine. There was a significant movement in the United States at the time called “America First,” members of which felt that not a single drop of American blood should be shed in defense of the British Empire or of European Jews endangered by Nazi Germany. One of the qualities of “America First” was, unfortunately, a deeply held anti-Semitism espoused by members like Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh, the American hero who was the group’s most popular spokesman across America. There were tens of thousands of people who felt that this “immigrant Jew” Irving Berlin was being presumptuous for writing about God, and about God blessing America. He wasn’t a member of the favored Christian majority, so “America First”-ers didn’t even consider him truly American. They felt he had no business writing a song that some people thought should be the national anthem. So yes, Berlin was spoken out against, and he was preached against from pulpits across the United States. I think he was more acclaimed than damned, but he was damned by a lot of people and it was a very, very scary time.

JJM Echoes of today…

JK Yes, “America First” came back, promoted by people who have no understanding of its history.

JJM Regarding “White Christmas”…Did Berlin realize at the outset that what he written had the potential for such widespread appeal?

JK He was always ambivalently confident about what he had written. When he first wrote “White Christmas” he barged into his office one morning at 9:00 AM, waving some sheet music and saying that he had just written a song that “not only is the best song I ever wrote, it is the best song anybody ever wrote.” He said that, but he was a nervous creator, and he didn’t really understand how powerful that tune was going to be – and I don’t think anybody understood it until Bing Crosby made a recording of it that connected with so many young American soldiers and sailors overseas who were deeply homesick and terrified. Their reaction to this powerfully nostalgic song helped turn Crosby’s record of it into the biggest seller of all time.

JJM It was thought that another song from Holiday Inn – the movie in which Crosby sang “White Christmas” – was going to be the big hit…

JK Yes, “Be Careful, It’s My Heart,” which nobody remembers today.

JJM Berlin’s contributions to World War II were significant. When he wrote “White Christmas” he couldn’t have predicted the scope of its cultural importance. Hearing Crosby sing that song overseas was the highlight of many a soldier’s life…

JK Yes, it meant so much to so many soldiers, but that wasn’t all Berlin contributed to the war effort, by any means. He toured This is the Army across the country; a movie was also made of it. The Army then asked Berlin to take the show to England, where only recently the Battle of Britain had been won. London had been bombed heavily, and when Berlin took the show there it served as a great morale booster. After that the Army asked him if he would continue the tour in Italy, where the war was still being fought. Berlin agreed and took the show up through the Italian peninsula, often just a couple hundred yards behind the Fifth Army as it fought the Germans up to Rome. He and his cast performed for Army audiences made up of battle-scarred and shell-shocked soldiers who were trucked in from the front lines, in desperate need of some diversion. The show was so close to the fighting that exploding bombs and shells could often be heard over the music. Berlin then took the show on to the South Pacific, traveling island-to-island, often in danger, as the Army and the Navy fought their way toward Japan.

JJM In 1955, President Eisenhower honored him…

JK Yes, Eisenhower presented him with a congressional gold medal in recognition of Berlin’s great patriotic services, which I think was one of the high points of Berlin’s life.

.

A musical interlude…Fred Astaire sings “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” [The Orchard]

.

JJM Like most of his generation, he wasn’t too fond of rock and roll…

JK Yes, but rock and roll loved Berlin, and they grabbed on to a number of his songs. I do feel a strong comparison between Irving Berlin and John Lennon and Paul McCartney, whose many wonderful songs — in their composition, their quality, and often in their bittersweetness —sometimes remind me of Berlin. I know that both Lennon and McCartney suffered the early loss of adored mothers, and I think that sorrow made its way into their music. Also, Berlin had a songwriting trick or habit that showed up in his greatest ballads, an alternation between major and minor modes, and Lennon and McCartney often did much the same thing.

JJM You wrote, “On the face of it, Irving Berlin had everything that humans yearn for: wealth, fame, unparalleled professional success, love, family. What he lacked was control over a perilous world, and over his own mortality, which he would have felt ever more keenly as he approached threescore and ten.[70 years old].” As you touched on earlier, Berlin seems to have suffered from a lifetime of depression…

JK I think he did and I believe you can hear that indirectly in some of his greatest numbers. “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” – which he wrote for Fred Astaire to sing to Ginger Rogers – is a brooding, difficult song. It’s a gorgeous song, but it’s not a happy one. Consider the lyrics, “There may be troubles ahead, but while there’s music and moonlight and love and romance, let’s face the music and dance.” And “Before they ask us to pay the bill” – what eerier lyric is there in the Great American Songbook than that? That is talking squarely about death, about which Berlin had such a deep consciousness. I think World War II underlined that again and again for him, and I also think the war exhausted him physically. The exhilaration of touring This is the Army, of singing and performing in it, made him feel like a young soldier, but he was in his mid-to-late 50s and ultimately the tour wore him out.

When the war was over he had a huge success that came about by accident – Jerome Kern was going to write the music for the show Annie Get Your Gun but died suddenly. Berlin was then asked by the producers Rodgers and Hammerstein to step into the breach, and he wrote a great score for the show, which was a smash hit. But a couple of years later, as Berlin turned 65, he fell into a clinical depression, for which he was hospitalized for several years in the 1950s. He recovered in the early 1960s and wrote one last musical, Mister President. But the show, which wasn’t in tune with the times, was a big flop, and though Berlin took the failure like a pro, it was a sad note to end a career on. He lived out the rest of his years as a grouchy recluse, but there were sparks of light. A huge consolation to him was his family – he had three daughters who had families themselves, and he loved having grandchildren. He also had longtime friendships — including those with Fred Astaire and the songwriter Harold Arlen — that he carried on over the phone and by mail. These relationships consoled him in his later years, but he was not a happy old man. We all think we want long life – Berlin died when he was 101 years old – but it can be a curse as well as a blessing.

JJM Any possibility that there is unpublished music by Irving Berlin?

JK I don’t think there is. The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin, edited by Robert Kimball and Berlin’s middle daughter Linda, has all the published songs in it, and there were close to 1500. Berlin himself liked to say “I wrote more bad songs than anybody,” and there are a number of bad ones, but the majority of them are good or great. I also spent a lot of time at the Library of Congress in the Irving Berlin Collection of the music section, looking at all his papers. Every song he wrote, every lyric he wrote, has been put into The Complete Lyrics, so there isn’t some trove of unpublished material. It isn’t like J.D. Salinger, who supposedly left thousands of pages that are going to be published at some point. Berlin published what was best, and sometimes what was his less than best, and there is an awful lot of it. His work, and his life, are a huge achievement.

.

___

.

“Just hope that heaven above

Will send you someone to love

Who’ll keep the blues away

While you’re growing gray”

.

“Irving Berlin’s final lyric, dated September 2, 1987, eight months before his hundredth birthday. No music is known to survive.”

-James Kaplan

.

.

Al Aumuller, World Telegram staff photographer /Wikimedia Commons/ Public domain

Irving Berlin, from a larger photo of him with Rodgers and Hammerstein and Helen Tamiris, watching auditions on stage of the St. James Theatre, 1948

.

.

Listen to a 1944 recording of Bing Crosby and Eugenie Baird singing Irving Berlin’s “Always”

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Irving Berlin: New York Genius

by

James Kaplan

(Yale University Press)

.

___

.

.

.

photo by Erinn Hartmann

James Kaplan, author of Irving Berlin: New York Genius

.

James Kaplan has been writing acclaimed biography, journalism, and fiction for more than four decades. The author of Frank: The Voice and Sinatra: The Chairman, the definitive two-volume biography of Frank Sinatra, he has written more than one hundred major profiles of figures ranging from Miles Davis to Meryl Streep, from Arthur Miller to Larry David

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on February 7, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

Click here to read our interview with Dominic McHugh, co-author of .The Letters of Cole Porter, and click here to read our interview with Richard Crawford, author of. Summertime: George Gershwin’s Life in Music

.

.

.

I think I have just read the greatest interview of my life: deeply personal, insightful, simple and accessible so that when I suggest to my Swedish husband that he read it, he just might (he being a lovely American Songbook pianist himself).

I can’t thank you both enough. Here I always thought that Berlin’s living till 101, married to a wealthy woman made for an idyllic life. The interview has given me a whole new perspective about life and what it is I want.

PS

The first ever film my daddy took me to see was “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” with, I think, Tyrone Power. (must check). So it’s safe to say, I grew up with the lyrics and music well fixed in my consciousness and repertoire.