.

.

photo by Jennifer Cooper

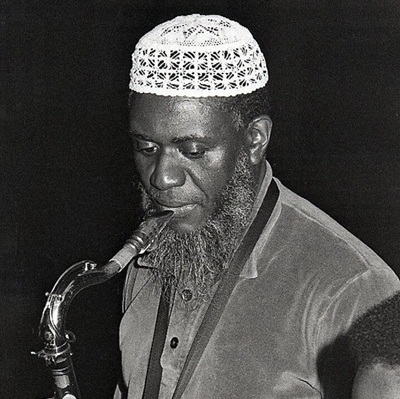

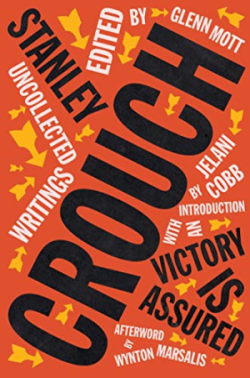

Glenn Mott, editor of Victory is Assured: The Uncollected Writings of Stanley Crouch [Liveright]

.

.

___

.

.

Dear Readers:

…..The introduction to this interview is a little unusual, because the subject of it involves someone who had a hand in changing my life.

…..When I began Jerry Jazz Musician in 1999, I didn’t know my way around publishing. While I wanted to be a writer when I was a kid, that dream was dashed when my grades didn’t allow me the sort of education that could result in an actual paying job. I sulked for a time, thought the world was cruel, and relegated myself instead to what turned out to be a career in the entertainment software business, mostly hustling records and videos to distributors and stores that have subsequently been replaced by the “magic” of streaming services.

…..But my dream to write and to publish remained, so I forged ahead with this site, which allowed me to write and publish in “moonlight” while holding a real job.

…..In 2001, the Ken Burns documentary Jazz was broadcast on PBS, and my eyes opened wide to the notion of transitioning Jerry Jazz Musician from a place where music and jazz-related products would be offered for sale, to an online magazine that would focus on the history of the music, and how it interacted with the culture of the 20th Century.

…..It sounded great, but I had little time for it, and I had virtually no idea what I was doing. I couldn’t program html code – knowledge required at the time to build a web site – nor did I have any real contacts in the jazz world.

…..But I forged ahead. I looked for a niche that would interest me, and began creating features that other websites or jazz publications weren’t – for example, exploring the historic connections between literature and the music, and, in particular, the impact figures like Ralph Ellison had on jazz. His views on the affects of the music on American culture were mesmerizing to me, and I read his work and those of jazz writers from his generation with great passion.

…..This direction didn’t result in great financial wealth – far from it. But it injected me with an enthusiasm for writing I hadn’t felt since I was a kid, and, interestingly, three serious writers were taking notice. Nat Hentoff, the legendary critic and columnist who knew more about jazz in his pinky toe than I ever possibly could, wrote me emails of encouragement, and eventually accepted my phone calls to talk about my path. I interviewed him several times, and he even thought I should publish a book of my interviews I had published on Jerry Jazz Musician with biographers of historic musicians and literary figures. He even insisted that he could help me find a publisher. Gary Giddins, the most gifted jazz writer and biographer (of any genre) of his generation, agreed to do a series of phone interviews with me that became a 15-column series, “Conversations with Gary Giddins,” resulting in extraordinary content that I continue to take pride in, and that I encourage readers to enjoy. And finally, Stanley Crouch, the passionate, often controversial Village Voice and New York Daily News columnist went out of his way to encourage me. We had numerous phone calls, interviews, and email exchanges – each one leaving me spirited and energized to, as he would tell me, “keep goin’!”

…..So, this trio of jazz royalty – Hentoff, Giddins, and Crouch – had me thinking that there were merits to continuing publishing along this path. And I did, even while retaining a “real-world” job. I am still “goin’!”

…..Thus, knowing them at the time I did and feeling their enthusiasm and advocacy was a remarkable, life-changing experience.

…..I saw Gary this summer while I was in New York, and a better person and more intelligent lifelong proponent for jazz music does not exist. Unfortunately, we lost Hentoff at age 91 in 2017, and, in September of 2020, Stanley died at the age of 74, seven years after he completed “Part One” of his biography of Charlie Parker – a volume the world of jazz had been anticipating for decades.

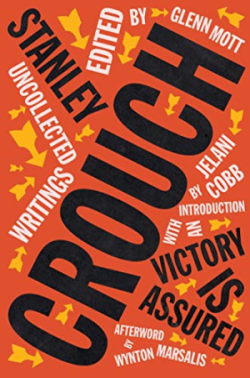

…..In our email correspondence, Stanley always signed off with his signature message “V.I.A.” (Victory is Assured). That sign-off was known to many, and is the title of an anthology of his uncollected writings, edited by his longtime friend and “American Perspectives” syndicated newspaper column editor Glenn Mott.

…..Crouch was an essayist, newspaper columnist and MacArthur Foundation genius, and when he died, jazz music lost a vital voice. He spent his life devoted to the art, once describing it as “the highest American musical form because it is the most comprehensive, possessing an epic frame of emotional and intellectual reference, sensual clarity and spiritual radiance.”

…..His views on jazz, politics, and race frequently sparked outrage or applause, and were almost certain to provoke debate. He was an early advocate for and artistic consultant of Wynton Marsalis, and along with Marsalis and the writer (and Crouch mentor) Albert Murray, helped establish New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Center. These relationships and his efforts will have an impact on jazz for generations.

…..Mott writes of Crouch: “Beloved yet cantankerous, Crouch delighted and enflamed the passions of his readers in equal measure, whether writing about race, politics, literature, or music.” The book is made up of writings never before anthologized – and some were discovered on his computer, unpublished anywhere until now.

…..When I learned of this book, I didn’t hesitate to reach out to Mr. Mott, who in addition to serving as Stanley’s editor was a close friend. While we have never met, we shared an admiration for Stanley’s career and humanity. Sure, he was complex and controversial, but Stanley was passionate about what he believed in, and he believed in the intricacies of America, and how jazz interacted with it – which, thanks to my experiences with people like Nat, Gary, and Stanley, is what I attempt to communicate on this publication.

…..In this January 23, 2023 interview, I had the privilege of discussing Mott’s work with Stanley, and Victory is Assured, this posthumous anthology of extraordinary, thought-provoking uncollected essays.

…..I hope you enjoy…

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

.

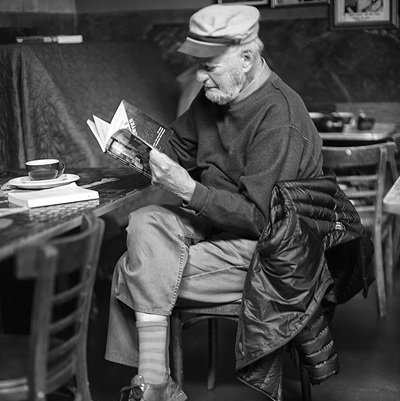

photo by Michael Jackson/jackojazz.com

Stanley Crouch playing drums at the Jazz Journalists Association awards at B.B. King’s, New York City, 2004

.

“Stanley’s death in September 2020 came amid a season of woe. We failed then, amid the welter of hardships and the titanic scale of our losses, to give his departure the attention it warranted. One potential definition of a pandemic is a season in which death outpaces your ability to properly reckon with it. This collection, on some level, is a fitting remedy, an attempt to do for Stanley what he had done for Lionel Mitchell, his encomium written in the miasmic fog of a different pandemic, almost forty years before. So here is Stanley Crouch, archival like an old Joe Louis newsreel, a showcase of what made him truly great. Look at him now: back in the ring, klieg lights beaming, he feints and he weaves. He works his combinations and lands shots you never expected him to throw – the ones you never saw coming. He finds victory in the very pursuit of victory – precisely the way he always did. Champions, he seems to be telling us, are not made at the end of the fifteen rounds. They’re created the moment that, despite titanic odds, they climb in the ring in the first place.”

-Jelani Cobb, the dean of Columbia Journalism School and staff writer at The New Yorker (from the Introduction to Victory is Assured: The Uncollected Writings of Stanley Crouch)

.

___

.

JJM What is your background, Glenn?

GM By trade I’m an editor and journalist and poet, living in Brooklyn, off the coast of Manhattan. I spent a good amount of time working in China, and then for the Hearst newspaper syndicate in New York, which is how I met Stanley. At the time, he was writing for the Daily News, and I reached out to him about becoming a Hearst columnist. It helped Stanley because this was another source of income for the column beyond whatever agreement he had with the Daily News. And after his column there ended, I continued with him at Hearst until the end. The columns ran from 2004 to 2016. So, we worked together for many years and became friends.

JJM Did you know of his jazz background before you met him?

GM Stanley first came into my field of view after I moved to New York, where I would read his columns in the Village Voice. For quite a while, that’s all I knew of him – not the drummer with David Murray, or his programing for the Tin Palace – but through his reviews and liner notes. I also remembered him as a regular on Charlie Rose, and in the Ken Burns films. What brought us together was my acquaintance with an editor who was putting together a book on Charles “Teenie” Harris, the great Pittsburgh Courier photographer known as “One Shot” Harris. She asked me who I thought could write an introduction for the book. My first thought was Pittsburgh native August Wilson because so many of Harris’s photographs were taken in the Hill District where Wilson grew up. When Wilson wasn’t available, I immediately recommended Stanley Crouch – you couldn’t get better than Stanley for that assignment, and he wrote a terrific introduction, which is included in Victory Is Assured: Uncollected Writings. That piece is classic Crouch – he writes about Pittsburgh and the Hill District and “One Shot” Harris, but reaches all the way back to the Iroquois, the Whiskey Boys, and the French and Indian War, the Pinkerton massacre at Homestead. It’s a big, history-filled essay.

JJM How would you describe Stanley’s writing style?

GM I think most people with knowledge of the work would describe Stanley as a polemicist, and his style as pugilistic. His was a muscular, physical style of prose in a direct line of Mailer and Baraka. Stanley was a mischief, and full of complexity and subtleties, complicated by his personal style. He was fearless, and his style reflected that. He trusted his own mind and was unafraid to take the outside position. He had a wide range of interests, his most overriding being jazz, democracy, and the imbalanced interests of humanity, which never-the-less, endures. He was pluralistic and provocative, and oftentimes his newspaper columns would be provisional or speculative, a laboratory for his curious mind and restless polemics. He would use the column to speak about events in the headlines, or what was going on in City Hall, or in profiles of myriad personalities, and he was very good at eulogies, particularly for those involved in the jazz life.

JJM Do you recall the first piece you read of his?

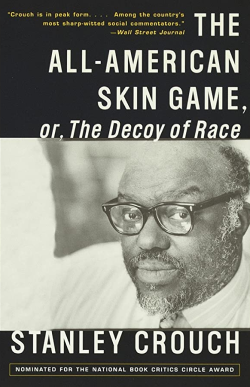

GM It must have been one of his Village Voice columns in the years I lived in the East Village and picked it up on a newsstand each week. I can’t recall the first piece, but the first collection I read was The All-American Skin Game, the sheer velocity of his prose blew me away; and then reaching back to Notes of a Hanging Judge, that first collection of his writing at the Village Voice in the late 1970s and 1980s. His style was annealed in those two books.

JJM I guess I don’t remember the first piece I read of his either, but I do remember having some challenges with his bombastic writing style. In the book’s preface you refer to him as a “physical intellectual.” What do you mean by that?

GM Well, Crouch was an estimable man, who had not come from a place in life where ideas could remain abstractions. He got under people’s skin, literally and metaphorically. There was often controversy around Stanley’s bombast, which was part of the effect – to challenged orthodoxy and reroute established patterns of thinking. We know about his complications with musicians, Miles Davis or Cecil Taylor, for instance, with other critics, particularly what he considered middling white critics, and with writers Amiri Baraka or Toni Morrison, but Stanley would defend his ideas tooth and nail, above and beyond where most critics would go, even then. He pushed boundaries and went places no critic now would dare to go. In no way a dilettante — he lived those ideas – and was Socratic in his methods. But he was not an ideologue, he was, in the best intellectual tradition, an enthusiast. Stanley was invested in primary causes, not received and habitual thinking. He was also just a very large, physical presence – when Stanley came into a room he had that swagger and a loping walk, he’s the only critic I know who could take a seat on stage during a set or be speaking to the bandstand while they were playing, and that would be tolerated. There was nothing subtle about his presence, he was full-throated and big-hearted, which is something many people may not know about him, but which comes through in Victory Is Assured, in the tenderness and affection, which alongside the bombast, can be seen throughout his work.

For this reason, Stanley wasn’t the easiest edit. His sentences could be vast, and when you edit for a general audience, as is the case with newspapers, often those sentences would have to be wrangled into shape. But, like any true professional, Stanley took editing well, and some of our best conversations happened during an editorial session. I tried not to get in the way of Stanley’s style. Over the years he was edited using various house styles – and for the most part I think his irrepressible voice comes through. There are pieces over his career that you could tell were encapsulated where he would have been much more expansive, and while his profile of Sonny Rollins is terrific, it is channeled through the imprimatur of the New Yorker magazine. Even before this book, I was indebted to Stanley’s editors through the years who broke the ground before me, especially: Larry Neal, Ishmael Reed, Wanda Coleman, Robert Christgau, Tina Brown, and Calvert Morgan.

JJM I’m sure it was a really difficult challenge to be his editor because much of his success was in his ability to enflame the passions of readers, and editing that out could have made him just another writer…

GM Stanley’s column was an opinion column, so he had free reign to write about what wanted to, but I would sometimes suggest a topic. For example, in the early 1990’s he wrote a piece in the Daily News about his use of the term “Negro,” and I asked him to revisit it for syndication. A lot of local editors chafed at that term. He responded by writing a piece about the people who gave that word dignity, why he uses it, and why, for him, the term African American was unwieldy. As you suggest, he wasn’t the easiest edit I ever had, and at times quite difficult. He had a looping writing style where he would start somewhere and then he’d improvise the middle. You might think he’s lost the way, but, like any good ensemble, he’d bring it back to cohere in the end, and it would be somewhere surprising. He took readers on a journey – even in a 650-word column you felt you were in the court of, and on the court with, Stanley Crouch.

JJM Was he personally persuasive with you? Did he change your mind on issues he’d write about?

GM He had a genius for reordering old pathways into new thinking. I miss Stanley’s “Hey, man . . .you see the thing is. . .” and what came next was always surprising and unpredictable. On occasion I’d ask him to add something as a defense or to clarify his opinion in a piece, and he always came through and would do that. He was happy to clarify meaning, to have more column space, and he was happy to give you more, but he would never soften his position – if anything, he would double down, giving it more power.

JJM Did you change his mind on anything?

GM I don’t know that I ever did. But I doubt it. I did more listening with Stanley. I’m not sure I could ever get in anything edgewise that would change his position, but I would often add to the conversation, or rather, fuel it with inquiry. Stanley loved to talk about some of the things that I knew. The same way he wanted to know what the man driving his taxi knew, or what a server at a restaurant knew. In our conversations, he was always interested in what was going down in China, for instance. And because I was raised in Missouri, we’d talk a blue streak about the history and mentality of the frontier, jazz and geography, and the politics of Tom Pendergast’s political machine in Kansas City, which kept the clubs roaring through prohibition and vice, and culminated in the syncopated KC style of jazz, from Andy Kirk and Mary Lou Williams, Bennie Moten and Charlie Parker, Lester Young and Count Basie. So, we enjoyed trading knowledge of the middle boarder and the Middle Kingdom.

JJM Stanley was a critic, and as a critic he opened himself up to lots of criticism from other critics and readers of his work. What do you know about Stanley that his critics don’t?

GM To understand Crouch, you have to understand his background and the streets he came from, and then you need to understand the epic journey of will that brought him to New York. He was born in South-Central Los Angeles, and while coming up he was a scholar, a drummer, a poet, and dramatist involved in the Black Arts Movement. He did extraordinary things as a young man that most people might not know about. For example, without a college degree and still in his early 20’s, Stanley talked his way into a faculty position at Pomona College, teaching theater and literature classes. He came under the influence of the poet Bert Meyers and the Joyce scholar Darcy O’Brien, and could have had a very comfortable academic career. But he left that behind, choosing to come to New York, and reinventing himself. Once he arrived, he gave up his hopes as a drummer and became a professional writer.

He was a polymath, there is no shorthand. So, when people from New York circles approached Stanley as if he were one of them, one of their newly-minted own, he would often remind them that they were not alike, which could rub people the wrong way and, sometimes, misunderstandings came to blows.

You know, there were people who believed that since he didn’t come from where they thought he should, he was therefore an autodidact, as if him coming from his working class background taught him nothing. So, I would say that to read Stanley is to understand him. He’s not asking you to agree with him. The likability of an essayist is what many readers want at the moment – someone they agree with, who validates long-standing positions, or gives them a paradigm of acceptable cool. But Stanley wasn’t about what was acceptable. And what contributed to making him complicated is that he evolved, and this evolution took place over his lifetime. For those who care to find out.

I call this posthumous collection of Stanley’s essays an intellectual autobiography, and what I tried to do is provide some of his early autobiographical pieces, and to give those space beyond some of the later polemical pieces, so he would be seen as a whole person, and not just as a representative of some form or another. He hated to be stigmatized as a critic. In order to understand his break with the electric avant-garde, for instance, it is important to understand his early activism, and his background in the Black Arts Movement, and his education in jazz, theater, and poetry. That shows up in this book.

JJM How did he see his role as a jazz critic?

GM Always authentic, never curried favor, someone who provoked with insight, rather than one who assemble consensus. He doesn’t want to persuade you as much as he wants to provoke thought. I write in the preface that he had the same view of criticism that Samuel Johnson did, which was to “improve opinion into knowledge”. Stanley saw himself less as a critic and more as a writer and creative force in applied thinking. I believe he saw the role of the critic as one that went beyond critiquing the performance, or the recording, or creating a year-end “best of” list. Understanding and defining the tradition was paramount to him, and he declared what his view regarding the jazz tradition was, which ran along the Armstrong/Ellington/Parker continuum. But that doesn’t mean that his break with the electric avant-garde was any less considered, or that he didn’t often return to them and listen.

People will often point to his break with Cecil Taylor, but what many don’t realize is that they were lifelong friends even beyond what came out in print – and he wrote many pieces over the years on Taylor, never losing touch. So, his break with the avant-garde wasn’t a break with any individual, it was a break with a facile definition of what the avant-garde might be. He was willing to entertain how the avant-garde was connected to a jazz tradition, but he didn’t see a lot of that being articulated. He may have wished someone would.

JJM In the book’s introduction, Jelani Cobb – a former student of Crouch’s and now dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism – wrote that ”his real opponent was pablum, and he fought what he deemed to be lazy thought that had gained public support.” For example, he rejected hip-hop and saw it as being “indicative of spiritual decay and bereft of any profound consideration of life and its meaning.”

GM Jelani is well versed to speak to that because he had a lifelong argument with Stanley about hip-hop in terms of its sonic value to the American tradition and the culture in general. Stanley spent an awful lot of precious time talking about hip-hop that might have been put to better use, but oftentimes his opposition to rap was the reason he’d be asked to appear on television. I think what he was most vehemently against was the gangster aesthetic within hip-hop that glorified the pimp and hustler culture that he had experience with in real life while growing up in Los Angeles, and I don’t think sat well with him. I know that calling women bitches and hos didn’t. His models, on the other hand, were people who wore tailored suits and silk ties like W.E.B. Dubois, Duke Ellington, and Miles. I believe he was arguing a cultural issue that had less to do with musicianship – although he could talk a blues streak about what was sampled and synthetic and electronic. He also had a soft spot for Biggie Smalls, which may come as a surprise to many. So, much of his dismissal of the music had to do with the worship of a gangster aesthetic for pecuniary interests.

JJM A little earlier you spoke about how you view this collection of essays as Stanley’s “intellectual biography,” and a “celebration” of him and his work. The book includes several never-before-published essays. How did you discover these, and do they reveal anything new about Stanley?

GM Stanley would often email pieces that he wanted me to read and consider for publication, or he’d ask if I knew someone who would. So, some of these were discovered on my laptop or his computer, and others were found in his archives at the Schomburg Center in Harlem. Paradoxically, the most difficult to locate were the ones that he wrote for the Village Voice during the height of his powers. Much of that material has never been digitized or archived in a central location, so it is extremely difficult to access. It would be a good thing for someone, an institution, to make that material accessible. And this is not just about Stanley’s work, but also Greg Tate, Gary Giddins, Bob Christgau, Manohla Dargis, Hilton Als, Gary Indiana, Jules Feiffer, and so many others.

I spoke with Giddins, Dan Morgenstern, and others who knew Stanley well and asked them what pieces were memorable to them, and of course everybody had their favorites, some of which had never before appeared in a collection, all of which I considered for this book. Many of these are classics: “Laughin’ Louis Armstrong” from the Voice is a great piece, one that was pivotal in rehabilitating Armstrong’s reputation. And then there is probably the best piece in the book, “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Dues: Duke Ellington at Disneyland,” which was published in Players magazine in 1976. It was hard for me to believe that piece had never been collected. There’s something very interesting to me about Stanley’s break with Los Angeles – he completely left it behind – but that piece is saturated with Los Angeles and Orange County and Disneyland, and is probably his best piece of reportage, bar none.

JJM And it’s an interesting reminder of how Disney used to program jazz in the park. I saw Count Basie there in the 1960’s, and in the 1970’s I saw Buddy Rich playing at a pancake house in the park’s “Main Street” section…

GM I can’t help but wonder what that pay day was like, and what their contracts included. I think Stanley writes in the Ellington piece that the band had to play three sets a day, which was a grueling schedule.

JJM Why is the book titled Victory is Assured?

GM Stanley would sign off on his correspondence, “VIA.” The first time he signed off that way to me I asked him what it meant, and he said it was “Victory is Assured,” which is the best title I could imagine for the collection. He knew things are never settled, but VIA confirms what he sometimes characterized as his “tragic optimism,” one that for him, goes all the way back to the U.S. Constitution – a set of highest ideals, while being realistic about the imperfectability of humans. It is the finest motto Stanley could have, one many knew intimately via his correspondence, and I thought it belonged as the title of the book.

JJM Along with his mentor Albert Murray, and Wynton Marsalis, Stanley was instrumental in the creation of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Of course, the programming for performances there has not come without its controversies, most prominently that many fans and critics believe not enough visibility has been given to the avant-garde or to musicians who create more in the European rather than the blues tradition. Did he talk with you about his experience with Jazz at Lincoln Center?

GM Not explicitly. We talked about the founding of Jazz at Lincoln Center, and his proposal to Mayor Giuliani, whom he asked to consider how the creation of this institution would leave a legacy – though who remembers that schmuck for anything of the kind. He was influential with people in New York City politics and government. A lot of people on both sides took umbrage with what he wrote about the NYPD, for example, in the Daily News. He had complex views on things, and they were the views of a realist who understood the workings of politics, power, and culture, and how those come together in the arts, and that’s what he brought to the campaign to create Jazz at Lincoln Center. As I understand it.

We did speak about the criticism he and Jazz at Lincoln Center would get for its traditionalist programming. There were those who, in principle well and good, wanted to kick the door in for the avant-garde. Stanley’s answer to that, right or wrong, seemed to be DIY, for them to put on a show – to build institutions in their own image, and to back it up with support, which is what he did. The other thing about Stanley is that he had about the thickest skin of anyone I’ve ever met. He was unafraid of his positions. Platonic forms, whether in ideas or of the institution, didn’t interest him as much as the idea that we should live in a world that acknowledges complexity, and that on the highest level of discourse, there can be no enemies. But one first has to get to that level of endeavor. Whether the programing at JALC recognizes all achievements in the jazz and blues idiom, specifically electronic music, is for others to answer. But the institution is nothing short of miraculous in its function, and in acoustics.

JJM What are the challenges of marketing Stanley? For example, when you were his editor, would you get pushback from publishers who didn’t publish him because they didn’t like his writing style, or who may not have liked his knack for being in the middle of public controversy?

GM Not from Liverlght [the book’s publisher], where my editor Bob Weil, who also knew Stanley, has been fully supportive of my editorial work. They set no limit on the collection. Bob had always wanted to do a book with Stanley but they were never able to. After I saw Stanley for one of the last times, I updated Bob on his condition, and the day Stanley passed I was speaking to him by phone. He asked if I felt Stanley left behind enough material to do a book that I would edit.

To return to your question about how Stanley may have been misunderstood. If you were to say that he was “misunderstood” in Stanley’s presence, he would have laughed, or felt you were currying favor in some way. To understand Crouch requires a close reading of him, and I’m not sure that’s something a lot of his critics have done.

JJM In the book’s afterward, Wynton Marsalis wrote, “You need to read him to know him.” What essays of his – whether in this collection or a previous one – would you recommend people seek out to get a good understanding of who he is?

GM If I were to point to one essay, I would say “Blues To Be Constitutional” from his collection The All-American Skin Game, which he thought highly of, and reprinted in Considering Genius. It’s a foundational essay and has probably been most anthologized, as well; including Robert O’Meally’s anthology, The Jazz Cadence of American Culture. The subtitle to “Blues To Be Constitutional” is a summation, “A Long Look at the Wild Wherefores of Our Democratic Lives as Symbolized in the Making of Rhythm and Tune”. It is an essay about the foundational document of the nation and how it helps explain the creation of jazz (specifically improvisation) as an American art form, by memorializing the amendment process in the human condition. If you were going to point people to one entire volume of Stanley’s work to get to know him, it would be the present one, or Considering Genius, which showcases his deep technical knowledge and passion for the music, and also serves the purpose of introducing someone to the greatness of the jazz tradition.

JJM What did he mean to the world of jazz?

GM Stanley did a great service to jazz, which is an art form that doesn’t have near enough supporters or articulation. And he did it his way, without a roadmap or manifesto. You could say he put his reputation on the line for it because he was willing to put positions out there and see what came back at him. And though sometimes the blowback was significant, he didn’t back down. He helped found an institution based on his ideals and what he considered to be the tradition of jazz, and he supported those he thought were doing the best work. His mentors Albert Murray and Ralph Ellison served that same tradition.

His central concept wasn’t original, it was the question of “What is an American?” For Stanley, I think that he looked at the dignity of the individual within a shared national improvisation, made up of wealth and culture and politics, but above all, daily lives. Democracy, as we have seen, isn’t easy, but he wanted everybody on board to acknowledge the full experience. There’s always a reason for what Stanley says, the voices he heard in his head were also those of prior generations of Americans.

JJM We talked a little earlier about how he saw his role as a critic…As a follow-up to that, how did he change the face of criticism?

GM Stanley inserted himself right into the argument, which was ongoing and long running. It goes back again to the American project and his essay “Blues To Be Constitutional,” and many more, where he would insert himself into big American ideas that had always been there and had always been under consideration. So, what he brought to criticism was always more than just writing about the evening’s performance – he would put the performance into context by writing about the major themes, the difference between greatness and mediocrity, between justice and injustice. He wasn’t just for a great cause; he was for all great causes. It was expansive work.

And that goes back to your question about his style, which was so unique because of the way that he reaches back into history, projects forward into the highest ideals, and can do all of that while writing about a single performance in the present. His criticism takes you on a journey. I think that people underestimate how close a reader and listener he was, and he probably gets that from being a poet.

JJM And, say what you will about his style or his preferences, but he was in the clubs all the time. 15 years ago I went to a show with him at the Village Vanguard where I experienced his close, intense listening. During the performance, he left our seats at the bar and walked to the stage, placing a chair directly behind the drummer, and he sat for at least ten minutes. He seemed so comfortable in his own skin…

GM He was always in the clubs and out on the town, and seemingly everyone has a story about how Stanley would show up at a book party or funeral or jazz club and he was so unmistakable, and so comfortable.

JJM Did he talk to you about favorite clubs or performances?

GM I remember something he said about Elaine’s, a clubby restaurant on the Upper East Side frequented by actors and writers and celebrities, where he’d see an amalgam of New York’s cultural A-listers – the likes of Joan Didion, Nora Ephron, Mario Puzo, Pete Hamill maybe one night, and Bobby Short, George Plimpton, Woody Allen, Mia Farrow, another night – and Stanley loved that room. He wanted to be in the mix. He wasn’t somebody who stayed at home or had a bitter pen with an academic view of things. He told me that when he first came to New York, everything he heard was great about the city ended up being smaller or more disappointing than what he was told to expect – “except Elaine’s.” And that was due to Elaine Kaufman, who adored Stanley.

JJM He came from a time when jazz writers who preceded him like Dan Morgenstern, Whitney Balliet, Martin Williams and Ralph Gleason were writing essays about musicians’ performances and their recordings, and how they fit into the history of the music. Music criticism was very cerebral at the time, and major publications invested in jazz writers. There is little of that today, where criticism is often relegated to 100-word reviews in magazines and on websites and personal blogs.

GM Right. Well, Stanley was there, and his work was made from in-person experience. Maybe we’ve lost that. We’ve lost, in a way, the public. And its counterpart, the public intellectual. Who has rushed in to filled the spaces once occupied by people like Whitney Balliet, or for that matter, Didion, Robert Hughes, Christopher Hitchens? The apparatus doesn’t exist. Or if it does, there’s a new paradigm being born. A few magazines, and the Substack subscriptions. We’ll see how that goes. There may just be fewer writers who have a broad public forum. And while it has provided visibility for many, I don’t think the digital world has yet provided a space for the extended attention spans needed on that level of discourse. Though there are still attempts, to varying degrees of success, to facilitate long form journalism.

JJM That’s were Stanley was so gifted as a writer – he would communicate his opinions in such depth and meaning. He wouldn’t just write a brief review of a bass player’s new CD – he’d commit 300 words to comparing the bassist to Ron Carter and to Carter’s own background…

GM And decades of writing liner notes! Stanley had that authority, and was still able to speculate out loud. He was sure of opinions he’d built over a lifetime of listening and consideration.

JJM One of Stanley’s literary heroes was the novelist Saul Bellow, who shared his opinions about the world through his memorable male characters, and it’s possible Stanley saw a bit of himself in that muscular style of writing…

GM If for Hemingway all of American literature goes back to one book by Mark Twain, then we could easily say for Stanley, everything goes back to Herman Melville and Moby Dick. He never tired of talking about what that book meant to him, and how representative it was of what he was trying to communicate, which was an expansiveness and an unexploited realism. It may have been the model, more than any other tome, for Don’t The Moon Look Lonesome, his only published novel.

JJM What was Stanley’s vision for America?

GM Hey, man . . . Jazz and blues for tomorrow. Just keep swinging.

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Victory is Assured: The Uncollected Writings of Stanley Crouch

edited by Glenn Mott

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read an excerpt from the book

.

A critical review of the book:

Stanley Crouch’s development as a critic is on full display in this standout collection of 58 essays, described by Mott in his preface as a sort of ‘intellectual autobiography.’ ‘Diminuendo and Crescendo in Dues’ is a stunning account of Duke Ellington playing at Disneyland in 1973, while “The King of Constant Repudiation” delivers a takedown of what Crouch considered phony activism: he writes of critic LeRoi Jones that ‘he has almost completely traded-in a brilliant and complex talent for the most obvious hand-me-down ideas, which he projects in second-rate pool hall braggadocio.’ Nor did Crouch sympathize with hollow notions of machismo—he writes in ‘Miles Davis, Romantic Hero’ about finding in Davis’s performances ‘public visions of tenderness that were, finally, absolute rejections of everything silly about the version of masculinity that might hobble men in either the white or the Black world.’ Most of all, it is Crouch’s abiding humanism that comes through, casting a critical eye on ‘those ‘race men,’ Black or white, who think they love Black people but only as receptacles for theories that use data to remove the mystery from life.’ This is an essential collection for fans of Crouch’s writing, or anyone interested in the art of cultural criticism.

Publishers Weekly, starred review

.

.

___

.

.

A handful of interviews/programs featuring Stanley Crouch

.

Crouch in 2008 lectures on the culture of rap music, and the rapper 50 Cent

.

.

In this 2013 conversation with Jeffrey Brown of PBS, Crouch talks about his biography, Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker.

.

.

A 2013 Jazz at Lincoln Center production…Part 1 of Stanley Crouch discussing Duke Ellington

.

.

A short film produced when Stanley Crouch received the 2019 NEA Jazz Master Award

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read Jerry Jazz Musician interviews with Stanley Crouch

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publishing efforts of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

This interview took place on January 23, 2023, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.