.

.

.

.

photo by Bouna Ndaiye/used by permission of Gerald Horne

Gerald Horne, author of Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music

.

___

.

.

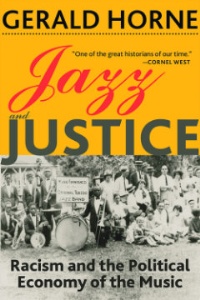

…..Jazz music — complex, ground breaking and brilliant from its early 20th century beginnings — would eventually become America’s popular music. That it did so in the face of the severe obstacles of blatant racism and sexism, organized crime and corrupt labor exploitation so prevalent in America at the time is at the heart of historian Gerald Horne’s new book,. Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music.

…..This book is a unique and often disturbing history of a popular music created and nurtured during the complexities of the Jim Crow era, and is a continuation of the work Horne has devoted his career to – writing histories on fights against colonialism, fascism and white supremacy that ultimately provide readers with new perspective.

…..In a January 17, 2020 conversation with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, Horne – the John J. and Rebecca Moores Professor of African American History at the University of Houston, and who is described by Cornel West as “one of the great historians of our time” – talks about the exploitation of musicians of color and women that was profound within the economy of jazz music during its most glorified era.

.

_____

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Parker, Tommy Potter, Miles Davis, Duke Jordan, and Max Roach, Three Deuces, New York, NY., ca. Aug. 1947

.

“Scholar Frederick J. Spencer is not far wrong in concluding recently that ‘it has become an accepted fact that jazz musicians tend to be more liable than other professionals to die early deaths…from drink, drugs, women [sic] or overwork.’ The venues for their performance – speakeasies, clubs – encouraged drinking and often were controlled by unsavory characters not opposed to using violence to attain goals. According to Spencer, a few jazz businessmen even preferred to hire addicts: ‘Some record companies and club owners would only hire junkies. With them they could be sure they wouldn’t insist on their rights.’ In addition, according to scholar Ronald L. Morris, ‘Most leading jazz entertainers after 1880 were closely allied with racketeers,’ and the impresario and producer John Hammond believed no fewer than three in every four jazz clubs and cabarets of this distant period were either fronted, backed or in some way managed by Jewish and Sicilian mobsters,’ though those of Irish origin were also prominent.

“The new music, in short, got off to a rocky start, navigating – and influenced by – war, pogroms, racism, and adverse working conditions. Yet these formidable barriers could not restrain the rise of a music that proved to be sufficiently potent to overcome.”

-Gerald Horne

.

___

.

JJM Good morning, Gerald. As an introduction to our readers, I would like to read a short description of your career found on your Wikipedia page, which describes you as “A prolific author who has written books on a wide range of neglected but by no means marginal or minor episodes of world history. He writes about topics he perceives as misrepresented struggles for justice, in particular.communist.struggles and struggles against imperialism, colonialism, fascism, and white supremacy.” You are also described as being a Marxist and, of course, a scholar. You are currently the John J. and Rebecca Moores Professor of African American History at the University of Houston. Cornel West describes you as “one of the great historians of our time.” It’s a great privilege to have you with me today.

GH It is my pleasure.

JJM How long have you been a fan of jazz music?

GH I was born in St. Louis, Missouri. I grew up down the street from the Bowie family, which included Lester Bowie of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, his brother Byron Bowie, who was also a musician, and their younger brother Joe, a trombonist who played in bands of my younger brother Marvin, a leading guitarist who has played all over the world for years. My father hails from Mississippi, and we grew up with musical instruments all around us. Like many black people, I grew up in a musical household. Of course, since that time I have developed other interests, but, that interest has stayed with me.

JJM What kind of music would your parents listen to when you were a kid?

GH Well, I would say the blues, of course, which is the music we refer to as “jazz” largely springs from. As noted, my parents hailed from Mississippi, which, as you know, has a thriving blues tradition. Mississippi is just across the Mississippi River from New Orleans, which, as my book suggests, has been thought to be the epicenter and the home of the music we call “jazz,” and there is a thriving black musical culture in the Mississippi River basin, which is one of the reasons why Memphis, which is also part of the Mississippi River basin, has also claimed parentage with regards to the origins of jazz music. Not to mention my own home town of St. Louis, Missouri, which also sits along the Mississippi River, with many of the black folks in St. Louis having roots in the South, down near Mississippi.

JJM Your book tells many stories about challenges jazz musicians of color and women faced from the time of the music’s beginnings. You wrote; “The new music got off to a rocky start, navigating – and influenced by – war, pogroms, racism, and adverse working conditions. Yet these formidable barriers could not restrain the rise of a music that proved to be sufficiently potent to overcome.” What is the goal of your book?

GH I think the book that we are discussing has to be seen in the context of my other work, and also in the work I am presently doing. Also, congruent with that brief description you read from Wikipedia, that is to say it’s an important struggle, and I think that in order to explain and comprehend this torturous journey from enslavement to whatever it is that we endure now – that is to say black people in particular – it is very useful to understand these past struggles, because I think that they provide pointers with regard to how to conduct ourselves in struggles today. Often times they provide inspiration and often times they provide instruction on what to avoid. In any case, I was also trying to make an intervention with regard to “music studies” and “jazz studies.” As you know, from having read the book we are discussing, it is mostly history. There is not that much musicology in this book, and that was intentional because I would like there to be a kind of shift in the balance with regard to “jazz studies,” that is to say a shift towards history, which is what I have done with the two books I wrote on film history. And, once again, it is not so much interpreting what is on the silver screen, it is more about the struggles that eventuate on the silver screen. It is not that I am trying to disparage or discourage forms of music interpretation or film interpretation, but I would like to encourage more historical analysis, because, speaking just personally and subjectively, I find that quite useful in terms of current day struggles in 2020.

JJM What is your opinion about how the history of jazz has been told to date?

GH Well, that is sort of putting me on the spot! But, I will say this; there are numerous jazz archives that have not been tapped sufficiently by the scholars. I think of the fact that we have yet to have an adequate biography of Max Roach, for example, a percussionist with roots in the Caribbean, from the Great Dismal Swamp area of the Virginia-North Carolina border that also produced the slave militant Nat Turner to Brooklyn. Max, of course, was present at the creation of this turn in the music that we often times refer to as “bebop,” and went on to an illustrious career, not only as a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, but also – along with his comrade and companion Charles Mingus, the protean bassist with roots in Nogales, Arizona and Los Angeles – formed Debut Records in the 1950s, which was a pioneering effort.

And Max was also a soldier in the Black Liberation Movement, not just raising money, which many artists have done and which I articulate at some length in this book’s pages, but also a kind of political consultant to the more militant tendencies of the Black Liberation Movement. Now, the Max Roach Papers at The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. have all this information, and more, and I draw upon it quite a bit in my own book, and the late writer Amiri Baraka, also known as Leroi Jones, started a memoir or biography of Max that did not get completed, so all of his notes are in Max’s papers. One of the things I would like to draw attention to is for some scholar or writer to dive into the Max Roach Papers, because there is a biography there, waiting to be written. So, one of the things I was trying to do was to alert others to the riches in this field, which is why my book is so thickly footnoted.

JJM In 1966, Max Roach wrote “Black intellectuals don’t give much credence to this music. DuBois didn’t deal with the music…there are no black critics in any major publications on the music.” Were you in some way inspired by Max to write this book?

GH I would say “in part.” I would also say that music criticism, not only of the music we call “jazz,” but generally, is withering on the vine, which is an adjunct of the fact that journalism as an enterprise is withering on the vine. Look at the Washington Post, for example, which is presumably one of the leading newspapers in this country, that was sold to Jeff Bezos – who carries the reputation of being this country’s richest man – for what could be considered coins found in his sofa. And, if you consult with the investor class, they would not be surprised if the New York Times did not survive this decade. So, when you talk about the withering on the vine of jazz criticism or the fact that there are not that many black jazz critics, you not only have to look at the adjunct, which is the withering on the vine of the daily press, but also, of course, you have to look at racism. It is very difficult for a black writer, because of the formidable barriers of white supremacy, to support themselves as music critics. That is the friendly amendment I would add to what Max said in 1996.

JJM How does your studying the history of jazz from a Marxist perspective impact your view of the challenges that were faced by jazz musicians?

GH This ties into the previous point that I made, trying to show how material conditions shaped the trajectory of the music. For example, in the chapter titled “Hot House,” I talk about the musical turn known as “bebop,” and I try to connect that to material conditions in New York, which then, as now, was the epicenter of the music. In the early 1940s, the authorities took umbrage towards heterosexual dancing across the race line, and tried to circumscribe that, and within that context you see music move from a sort of dance music to a listening music, which is where it is today. My intent is to show how material conditions led to a change in the music.

It is also fair to suggest that another aspect of my book is the role of organized crime, in terms of the horrible working conditions to which musicians were subjected. It should be no revelation to suggest that organized crime factions are not the best employers – they do not create the most pleasant working conditions for those working under them. Likewise, I tell a story of St. Louis in the 1920s, where you have one faction spearheaded by the Ku Klux Klan, the racist terrorists who were trying to exclude black musicians altogether, facing off with organized crime factions who would like to exploit the musicians who do not want to be excluded – because they want to exploit them shamelessly. Perhaps surprisingly, the organized crime factions prevail, and black musicians win the curious privilege of being exploited shamelessly.

Likewise, with regard to musicians and their flight abroad, many previous writers have discussed Louis Armstrong’s roots in New Orleans – which given his pioneering role gives emphasis to the idea that the music was actually born in New Orleans – at one point in the 1930s feels compelled to flee the United States because of threats from organized crime. This is of course part of a larger tapestry, the story of what I call the “jazz diaspora.” Dexter Gordon, the lanky saxophonist from Los Angeles goes to Copenhagen; Miles Davis as you know spends time in Paris; my own younger brother spent considerable time in Japan, which has become a kind of epicenter, along with New York, for this music; you find many black musicians in Shanghai, China in the 1920s and 1930s; there are just too many examples to mention. To this very day, you have musicians who feel that they get a better shake abroad than they do in the land of their birth.

And of course there is the related issue of how this music has given rise to a number of, say, South African musicians who have mastered this music. I am speaking of the late Hugh Masakela, who patterns himself as a musician after Louis Armstrong, and Dollar Brand, now Abdullah Ibrahim, who in some ways is inspired by Duke Ellington of Washington, D.C., is, of course, South African. The list of the musicians with such roots is long, and in some ways that is connected to these black American musicians who fled abroad.

JJM The stories of black musicians leaving America and going overseas are pretty well known, maybe even to people who don’t consider themselves jazz fans. Milt Hinton, for example, said that in Europe there was an “acceptance of you just on the basis of you as a human being.” Abbey Lincoln said, “If it wasn’t for Europe, I don’t know what I would have done,” and Benny Carter talks of a hero’s welcome upon his arrival in Copenhagen. So, these are things that many of us have heard, but we may not think about the challenges they encountered over there, because, it couldn’t have been perfect, right?

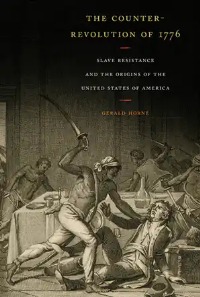

GH Oh no, but I should also say that that particular story also fits into other work that I have done. As you may know, I have written quite a bit about, for example, the 17th and 18th century and the origins of the United States of America. In fact, I wrote a book, The Counter Revolution of 1776, where I make the argument that, far from being a step forward for humanity, the process that leads to the formation of the United States leads to exponential expansion of the African slave trade centered in the country, heightened dispossession of indigenous folks, and also a particularly nasty persecution of the descendants of mainland enslaved Africans – that is to say, black people with roots in the region we refer to as “Dixie,” which then forces them, often times, to seek employment or refuge abroad.

The Counter Revolution of 1776, by Gerald Horne (NYU Press)

.

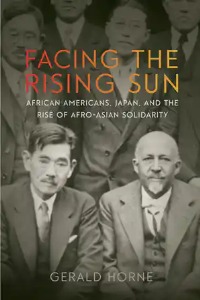

Facing the Rising Sun, by Gerald Horne (NYU Press)

Now, to be sure, there are no safe harbors, but these musicians should be taken seriously when they suggest that escape abroad was preferable to endurance in the land of their birth. And, what barriers did they encounter? Well, for example, there is a kind of protectionism in Britain which tried to limit the ability of these black American musicians to get visas and work permits so they could play in London. Of course, racism towards the people we now refer to as African Americans was not absent in Paris or Copenhagen or Vienna or other parts of Europe, however, I don’t think we should let the United States off the hook and play up the barriers that people had abroad because that has too often been the pattern. As a matter of fact, you can see how propagandists try to say that people all over the world hate black people so that can help rationalize their own nastiness, which I think is ludicrous and ridiculous, which is one of the reasons I have spent so much time writing about Asia. I have a new book that came out in 2018, Facing the Rising Sun: African-Americans, Japan and the Rise of Afro-Asian Solidarity, where I write about the reception of black Americans in Japan. As a matter of fact, I start out the jazz book talking about black musicians going to Yokohama, Japan in the 1930s, and how Japan, with its own race politics, tried making overtures to black Americans prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, which of course is a subject not traditionally addressed – how other people tried to turn the tables on the United States by making overtures to the black Americans so they could have allies once their country was attacked. So, that is one of the reasons why this book has to be seen in the context of the other books that I’ve written.

JJM You wrote, “Absence of a strong union led artists into problematic situations, such as recording under various names to escape adhesion contracts with record companies.” Was there a collective attempt by the musicians to organize?

GH First of all, let me say that I am a union person, a “union man,” to put it in gender terms. My father was a member of the Teamsters Union, I have been a member of various teachers unions, including being an official of my local union. So, I stand second to few with regards to my support of the union movement, but having said that, musicians unions could be problematic. Often times, you’ve seen unions operate as racist job trusts, that is to say that they seek to protect the interest of white wage labor, basically, and then shoo away black labor, or any other kind of so called “non-white labor.”

And then, with the rise of the Black Freedom Movement in the 1950s and 1960s that took place at the time of the so-called “colored locals” – that is to say, separate and unequal Negro locals of a larger union – there is a movement to liquidate these “colored locals” and have one big union. This on its face sounds peachy-keen, but what it often leads to is these “colored locals” losing their records, losing their headquarters, and not gaining positions in consolidating into the so-called interracial unions, whose white leaders cut deals with employers and clubs to exclude the black musician.

And this is taking place in the context of musicians who often times, as in the case of the saxophonist John Coltrane, practicing and working sometimes 13 – 15 hours a day. So, how are you going to spend this time required to master your instrument and still have time for union activism, or, in the case of Max Roach and the aforementioned Charles Mingus, still have time to run a record company on the side? This is really asking quite a bit. So, not surprisingly, it has really been an uphill climb for these musicians, for on the one hand they are trying to master their art, master their instrument, and on the other hand they are trying to escape adhesion contracts as noted – that is to say, one-sided contracts. Trying to escape terrible working conditions, and trying to escape the often-times malfunctioning union to which they must belong if they are going to get gigs. So it is a very difficult story. One of the things I will say, and I try to end this book on an “upbeat note” so people won’t close this book too depressed, by talking about how there has obviously been progress.

JJM You write about the conditions that the musicians were working under, all the while navigating this world that included the likes of record executives such as Herman Lubinsky of Savoy, Bob Weinstock of Prestige – which was known as the “junkies label” – as well as managers like Joe Glaser and Irving Mills. So, there are a lot of bad guys in this book…

GH Yes. I am not sure why in my remarks earlier I didn’t mention these scoundrels, but I certainly go to some lengths to detail their misdeeds in the book. For example, I talk about Irving Mills, who had a role in the career of Duke Ellington, the Washington, D.C. – born pianist, conductor and composer who leads an orchestra for decades, and Mills puts his name on some of Ellington’s leading compositions, which means that the descendants of Mills will reap the royalties even today, not the descendants of Ellington. You can see how this operates structurally, so basically these men you mentioned – Lubinsky, Mills, Glaser, Weinstock – are taking advantage of the structural issue of racism and bigotry being directed against people of African descent, which makes it easier to exploit them. Add to that the talent these musicians have for creating a certain kind of wealth, and when these factors of structural racism and wealth production are put together, it is ready made for these parasites to swoop in and take advantage. Then, reference the points I just made, that these musicians spend much of their time trying to compose, perform and master their instrument, it might be too much to ask them to be adroit and adept organizers too, although some of them have to be. So, it is a situation ready-made for exploitation.

JJM Despite these challenges you write about, some musicians did make attempts to respond to this racism through their business activities. There are interesting stories and anecdotes regarding this throughout the book, one of which involves the saxophonist Gigi Gryce, who in an effort to retain copyright and control of his music, among other things established a publishing company called Melotone Music. Talk a little about Gigi Gryce and the challenges he took on?

GH Just as with certain hip hop artists today, he tried to control the masters of his recordings. He tried to make sure that he had a hand in the business side, and he often times tried to encourage other musicians similarly situated to do the same. But Randy Weston, the towering pianist and composer who also spent time abroad, in his case in North Africa, speaks at some length in his highly recommended memoir about the difficulties Gigi Gryce endured that finally forced him to step back from the activist role that he had pursued. Weston suggests that there were those who took exception to Gryce’s activism and may have had a role in sabotaging his life.

Once again, I don’t want to leave your listeners depressed, so I should say that many musicians were able to overcome. Musicians like Max Roach contributed to the Black Freedom Movement, and Nat “King” Cole, who became extraordinarily popular as a singer and pianist, raises a significant amount of money for Martin Luther King and for the March on Washington in 1963. And then, it’s not only record company owners like Atlantic’s Ahmet Ertegun who become fabulously wealthy, you also have musicians like Quincy Jones, who despite past struggles are able to parlay their talent into significant wealth. So, for people who consider that to be a worthwhile accomplishment, there is something in this book there for you too.

JJM Gryce met a lot of obstacles, and it seems he ultimately put his instrument away due to financial troubles…

GH Well, this gives me an opportunity to take my hat off to previous scholars. For example, there was a book on Gigi Gryce (Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce by Noal Cohen and Michael Fitzgerald) that details this, and that is quite remarkable. It allows gives me an opportunity to go back to an earlier topic, which are the archives of these musicians – for example, the Max Roach, the Charles Mingus, the Dexter Gordon, and the Billy Strayhorn Papers at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C; the Errol Garner Papers at the University of Pittsburgh; and the Dave Brubeck Papers, presently at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California. Then of course there is this huge memoir literature. Think of all the books about Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus. Then there are the oral histories, and I particularly want to salute the Institute for Jazz Studies at Rutgers University, which has one of the more formidable libraries of biographies, autobiographies and memoirs of this music, not to mention archival collections as well. I also draw upon the oral histories of the Smithsonian Institute, which are found online, and they have a cornucopia of literature and oral histories of working musicians – Ron Carter, for example, the extraordinary bassist. Elvin Jones, the drummer who played with Coltrane, is also part of that oral history collection. So, obviously I could not have put this book together without these archives. I am sitting on the shoulders of all of those who come before me. I should make that clear because I don’t want to leave a misleading impression.

JJM What are some of the challenges female jazz musicians faced?

Mary Lou Williams, New York, ca. 1946

GH First of all, there are the stereotypes around the idea that there are supposedly certain instruments they are not able to master, believe it or not. Some of the stereotypes have been propagated by certain critics who shall remain nameless. Then there is the rampant sexism that they endure on the bandstand from their fellow musicians, and then there are the extraordinary pressures that are placed on them because of a kind of preexisting bias. We hinted a few moments ago about some of the substance abuse problems that many of the musicians were subjected to, and fell victim to, sometimes at the behest if not the instigation of unscrupulous club owners and record label owners, but Mary Lou Williams – one of the leading pianists at the time – fell victim to a degree of another sad, ancillary aspect of this music, which is gambling. I have quite a bit in this book about the rise of Las Vegas and the mob in post WWII, which is extricable from, on the one hand gambling and the casinos, and on the other hand opening up opportunities for musicians to play at these clubs, where they are exposed to this kind of vice.

Fortunately, once again I am sitting on the shoulders of those who come before me, because there has been a considerable amount of publishing of the tales and travails of women musician. Even today, if you look at a musician like Esperanza Spalding, there has been a fair amount of writing about the difficulties she has been subjected to that fortunately has not circumscribed her artistry – not only her bass playing, but her vocalizing. So, once again I take my hat off to those – not only these female musicians – but those who have written about these female musicians who created a record that I could then consult.

JJM Female instrumentalists were particularly discriminated against, and the saxophonist Vi Redd is one example. There were instances of male musicians packing up their instruments and leaving the stage when she appeared…

GH Oh, absolutely. Once again, we are fortunate that there are a number of oral histories that one can draw upon. As a matter of fact, people can go online right now and read or listen to oral histories of someone like Dorothy Donegan, which I draw upon at length in my own book, in which she details the travails she was subjected to.

JJM You write much about Kansas City, and you point out that there were more murders in Kansas City than Chicago at the time, yet you suggest the authorities in Kansas City were more preoccupied with “rousting Negro musicians and club owners…which may have played a role in the impromptu performances now known as ‘jam sessions.’” Perhaps many who love jazz music, and who love the notion of musicians packing up their instruments at three o’clock in the morning to play an impromptu set, would be interested in hearing more about this…

GH I am from St. Louis, and Kansas City is directly across the state, so I spent time in Kansas City doing research. Of course, one of the luminaries of this music, Charlie Parker, has roots in Kansas City, and it is difficult to talk about the rise of this music in Kansas City without talking about the corrupt political machine of Tom Pendergast, and of course his close relationship to a man who got his start in that political machine, President Harry S. Truman. So there is a story in the book about, once again, these Afro-American figures trying to carve their own path, to try to be able to appropriate the fruits of the creativity of this music, but alas, because they do not have sufficient clout in the political structure to use the organs of the state – meaning the police and prosecutor’s office – to crack down on black club owners, for example, which then stunts their ability to perform. Then, after the Pendergast machine comes under fire, there is a crackdown on clubs in general, which then leads many of the musicians to flee, with Bird, for example, moving to New York.

JJM There are several white entrepreneurs who often supported the plight of black jazz musicians – men like Norman Granz, Leonard Feather, John Hammond, and Dave Brubeck…

GH Yes, I take my hat off to Brubeck, because on the one hand, beginning in the 1950s, it is a white supremacist’s culture so he was being pushed forward as the face of this music, yet he did not capitulate to that kind of pestilence, in so far as he would not play in segregated venues and turned down good money in places like Alabama during the Jim Crow era – he would not play in those places. Once again, the record is clear that Brubeck was not necessarily singular, although one of the issues in his favor is that he left an archive; had these other musicians left an archive I would have been able to talk about them at length too. And actually, if I may, one of the reasons why New Orleans is often times singled out as the birthplace of this music is because Tulane University archivists and librarians at the beginning of the 1950s began taking down oral histories of elderly musicians who had knowledge and experience of the 1860s and 1870s, and if you had similarly farsighted archivists and musicians in the University of Memphis in the 1950s, perhaps we would be telling a different story about the origins of this music. That is, once again, a structural question with regards to “jazz studies” that should not be lost sight of.

JJM If you had a “top five” of songs of resistance to recommend, what would they be?

GH Well, you can start by looking at my chapter titles. For example, “Song for Che,” by Charles Haden, the celebrated bassist saluting the Argentine-Cuban revolutionary figure Che Guevara; “Haitian Fight Song,” by Charles Mingus; “I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to Be Free,” penned by Dr. Billy Taylor, which was one of Martin Luther King’s favorite songs of all time. So, those would be my top three, and, of course, “Alabama” by John Coltrane, which is a composition about the little girls who were blown to bits by a Klan terrorist bombing in Birmingham in the early 1960s.

Musicians have been on the case to a certain degree. I was part of the anti-apartheid movement, and I still recall the fund raisers that we did for the anti-apartheid struggles of the pro-liberation forces in southern Africa, where musicians like the late violinist Noel Pointer would contribute his artistry for free, as did South African musicians like Abdullah Ibrahim and Hugh Masakela. So, the musicians have pulled their weight, they have done their share – at least a good number of them have.

.

_____

.

“What does it mean for descendants of enslaved people to create a music embraced by the world and still be treated as second-class citizens, exploited, dehumanized, and subject to premature death? By following the money, the managers, the musicians, and the bodies, Gerald Horne gives us an enthralling view of jazz history from the underside. An essential contribution to our understanding of how racial capitalism shaped American music.”

-Robin D.G. Kelley, author, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

.

.

Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music

by Gerald Horne

.

.

Gerald Horne is John J. and Rebecca Moores Professor of African American History at the University of Houston. He has published more than three dozen books, including.The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism.(Monthly Review Press)

.

.

This interview took place on January 17, 2020, and was produced and published by.Jerry Jazz Musician.publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

Gran découvert pour moi fantasticooo gracias