.

.

Photo by Elise Hughey

Dave Chisholm, author of Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California

.

___

.

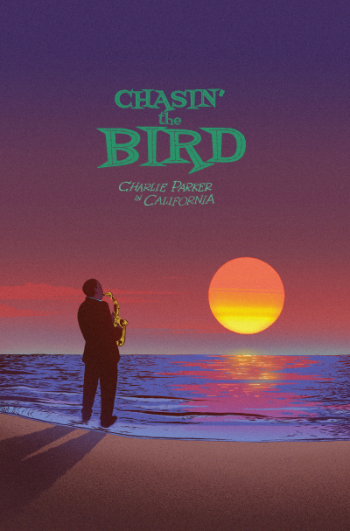

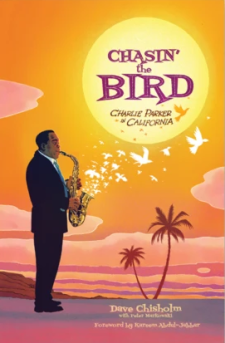

…..As part of the celebration commemorating Charlie Parker’s 100th birthday last August, the estate of Parker – an undisputed genius of modern jazz whose work paved the way for bebop and everything in jazz after that – commissioned the publisher Z2 Comics to create a graphic novel telling the story of his time in Los Angeles. The result is Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California by Dave Chisholm (with colorist Peter Markowski), a lovingly told yarn that adapts one of the darker chapters of Parker’s life and incorporates some of the characters and events he encountered while there.

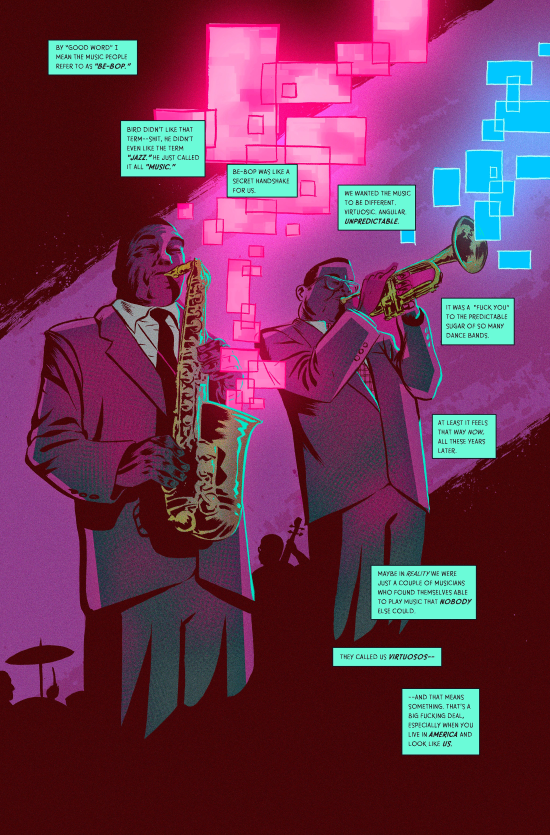

…..In 1945, Parker and Dizzy Gillespie traveled to Los Angeles for a two-month residency at Billy Berg’s Hollywood jazz club – the beginning of Parker’s raucous two-year SoCal adventure that culminated in a six-month stay at the Camarillo State Mental Hospital. Chisholm draws readers into Parker’s complex world in six colorful vignettes– among them his friendship with Gillespie, and his encounters with John Coltrane, the photographer William Claxton, the record executive Ross Russell (who signed Parker to his Dial Records label), and the artist Jirayr Zorthian (who hosted a “party of the ages”).

…..Parker’s story has been told many times before – at times unreliably – so why tell it now in a graphic novel? “As someone who is both musically and comics literate,” Chisholm explains, “my role is to treat the book as a love letter to both music and comics in a way that is an open door for people who have no experience with either one, to get them to say, ‘Wow, I didn’t know comics could do this,’ and people who didn’t know jazz music now have a bridge to it.”

…..This book is filled with stimulating, vibrant art, and reading it is a rich and satisfying experience, even to someone who last consumed a “comic book” about the time LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act.

…..In a December 22, 2020 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, Chisholm talks about his experience creating this gratifying book, one cited by Comic Bookcase as “one of the best graphic novels of the year.”

.

Note:

Enlarged graphics of the book’s pages featured within the interview can be found at its conclusion

.

.

___

.

.

“Chasin’ the Bird, this phenomenal graphic novel about the groundbreaking jazz musician Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker [is an] archeological dig into the legend that was Bird – and the man that was Charlie Parker. What is especially impressive is how Dave Chisholm and [artist] Peter Markowski capture in words and art, the spirit of Bird’s music, rooted in the traditions of classic music but reshaped into his own – and their own – personal expression. It is the universal quest each person embarks on to find their unique voice. Most are stifled along the way and so we look to others who, like Bird and Don Quixote, are ‘willing to march into hell for a heavenly cause.

“Even if it destroys them.”

-Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, from the Foreward to Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California

.

.

Listen to Charlie Parker play “Relaxin’ at Camarillo,” a composition inspired by his six month stay at Camarillo State Hospital in Ventura County, California, where he was sent in 1946 to recuperate from alcohol and drug addiction. In addition to Parker on alto, the recording includes Howard McGhee (trumpet), Wardell Gray (tenor sax), Dodo Marmarosa (piano), Barney Kessell (guitar), Red Callender (bass) and Don Lamond (drums)

.

.

JJM In an August 27 review of Chasin’ the Bird by Jackson Sinnenberg in Jazz Times, he writes that “Chisholm and Markowski offer one of the most balanced, human, and colorful depictions so far of a great musical enigma and genius.” Reading your graphic novel was a new experience for me, and I have to say I enjoyed it very much. So, congratulations, Dave, on this work. What is your first memory of hearing Charlie Parker’s music?

DC My dad isn’t a musician but he’s a big time music fan, and he listened to a lot of jazz music when I was a kid. I remember Sketches of Spain and a lot of Mingus, like Mingus Moves and Changes One and Changes Two and Let My Children Hear Music. He might have spun some Charlie Parker, but I don’t remember it, so I would say the earliest I heard Parker was in high school. Like most kids in America in the late 20th and early 21st century, I played jazz in the high school jazz band, which led me to explore the recorded history of jazz music, and I bought the Parker CD Yardbird Suite at that time. I listened to it and understood that he is obviously incredible, but without the proper historical perspective, as a high school kid it’s easy to listen to him years after he recorded it and come away thinking; “Yes, he is a good sax player.” Because Parker’s influence is so pervasive, a crappy sax player at your cousin’s wedding is pulling off half-baked Charlie Parker licks, so to the untrained ear, what’s the difference between the two?

Charlie Parker, Three Deuces, New York, N.Y., c. Aug. 1947

I must have first heard Parker casually in high school, but the magnitude of his accomplishments didn’t really fully land with me until I was well into graduate school, when I was able to grasp his contributions to music. There are certain figures in music history like Bach, Beethoven, Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker, and the more you learn about their contributions the more incredible their work becomes. You never really grow out of Charlie Parker – his music is something to come back to, and it’s always rewarding.

JJM In addition to being an artist and writer, you are also a musician?

DC Yes, I have my doctorate in jazz trumpet.

JJM Do you play in a band?

DC Well, not right now, although I did record some CD’s with my band. I did a graphic novel in 2017 called Instrumental which has an album of music that goes with it, and that’s the last piece of music I recorded that would also be a good representation of my trumpet playing.

JJM When were you approached to write Chasin’ the Bird?

DC The people who published Instrumental [Z2 Comics] have since pivoted to basically publishing a lot of music-based graphic novels, and the Charlie Parker estate reached out to them about doing a graphic novel to coincide with the centennial of his birth. Since the publisher knows that I’m a jazz guy, they contacted me and asked me to put together a pitch. This happened in August of 2019, and I received approval in mid-October, so the project came together quickly. I worked on spec after I made the pitch because I felt they would approve it, so I began work on it before I had a signed contract. I finished all of the line art in March of 2020.

JJM When you got the green light and began imagining this project, what was your vision for it?

DC When the publisher asked me to put together a pitch for a Charlie Parker graphic novel, the scope of it wasn’t communicated to me other than it was going to be about his time in California, so my initial idea was to have him at Camarillo, reflecting on his life in that space. I also knew I wanted to try to cover the legend of Charlie Parker and not just the factual, drier biographical stuff – even though his biography is not exactly dry. I wanted to dive into the myth making and legend about Charlie Parker and began toying around with ideas for doing so, and it hit me that the best way to do this – especially since the deadline was really short – was to present the story as told by a variety of different people whose lives intersect with Charlie during his time in California. The book is structured with each one of the six vignettes being colored by the unique perspective of the narrating figure. So Dizzy Gillespie’s perspective is different from Ross Russell’s perspective, for example, and everything about the storytelling will shift with each new perspective to show not just the many sides of Parker, but the many perspectives of him.

JJM I grew up with comic books but I don’t know much of anything about contemporary graphic novels, so this was a unique experience for me. While reading it I couldn’t help but wonder who your target audience is – it couldn’t be older jazz fans like me who don’t consume graphic novels. So, I am curious about what the business model for your book is.

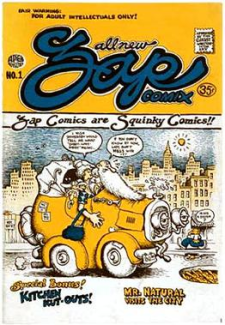

The February, 1968 cover of R. Crumb’s Zap Comix #1

.

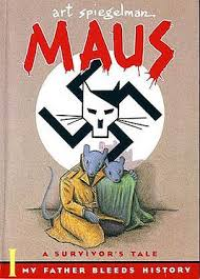

The first volume of Art Spiegelman’s Maus

DC The world of graphic novels and comic books has undergone a pretty radical transformation just in the span of my life. I was born in 1981, and when we look at the history of this media, in the ‘80s comic books were viewed as being something for kids, although there were certainly some underground comics that weren’t for kids like Zap Comics and Crumb and other hippie, counterculture comics. So the seed was planted there for what grew in the ‘80s, books that were critical of super heroes like Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, and then something like Maus, which completely upended the medium in terms of the seriousness and scope of the story, and these books began being taken seriously as literature and not just pulp.

What’s funny is that as I say this it sounds a hell of a lot like jazz music, doesn’t it? The history of jazz music is the same, where you have this music played in whore houses or at raucous parties, and even the word “jazz” was considered a filthy term. Then over the span of the 20th century you see seeds of high art evolving – for example the swing era evolving into Parker and bebop, making jazz a high art even though the masses saw jazz as a low art. And from Parker jazz evolves until you eventually see a Pulitzer Prize awarded to Wynton Marsalis’ Blood on the Fields in 1997, just a few years after Maus received a Pulitzer Prize. So, there are similar trajectories for both of these art forms.

Since the publication of Maus in the ‘80s the comic book world has undergone this weird transformation, where you have the monthly comic books that are throwbacks to those you read as a kid, but there are also graphic novels that sell huge numbers, in particular young adult graphic novels that deal with some pretty big topics and are critically acclaimed, some even treated as literature.

Regarding the target audience for this book, when you are dealing with Charlie Parker it is certainly not going to be a book for kids – it would be irresponsible and dishonest to tell the story of Charlie Parker but get rid of all the drug use and the womanizing. So, while it isn’t for young children I would give this a rating like “Teen Plus,” a book that can appeal to those in the gap between childhood and adulthood. If we were only aiming for people who read comics and for the people who listen to jazz, there is obviously a very narrow crossover between those two, and it would be a fool’s errand to publish this book, but our idea was to create a work of such high quality that the word of mouth among readers will spread. As someone who is both musically and comics literate, my role is to treat the book as a love letter to both music and comics in a way that is an open door for people who have no experience with either one, to get them to say, “Wow, I didn’t know comics could do this,” and people who didn’t know jazz music now have a bridge to it.

JJM The publisher of z2 books, Josh Frankel, said in a press release that “Jazz has always been a perfect complement to comic books, and certainly an inspiration to some of our greats as well. Robert Crumb would be proud.” Would you agree that jazz is a perfect complement to comic books?

DC While I can’t know for certain what Josh was referring to, I will say that, as I mentioned earlier, jazz history and the history of American comic books are somewhat similar. Both of these art forms were largely pioneered by minority groups – early comics in America were almost all done by Jewish Americans, and jazz obviously comes from Black Americans. Comics have gone from low art to high art over the course the 20th century, while still maintaining its original pulpy, low art feel. When we look at American superhero comics you see a character like Superman or Batman as someone who is constantly reinterpreted without losing its core essence, and it is reinterpreted by the unique vision of a single artist or an artistic team. This sounds a lot like a jazz standard to me. You could look into the history of a jazz standard like “All of Me” or “Body and Soul” and see all of the hundreds of ways these songs have been transformed by various artists and various individual voices and teams of people. For example, when Miles and Tony and Herbie and Ron and Wayne played a jazz standard at the Plugged Nickel, it was entirely different from the way it was originally written and recorded. Similarly, when Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely and Alex Sinclair made All-Star Superman, while it’s really different from Siegel and Shuster’s original Superman, it retains the essence of the original form.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1953 recording of Charlie Parker playing “Now’s the Time,” with Al Haig (piano), Percy Heath (bass) and Max Roach (drums)

.

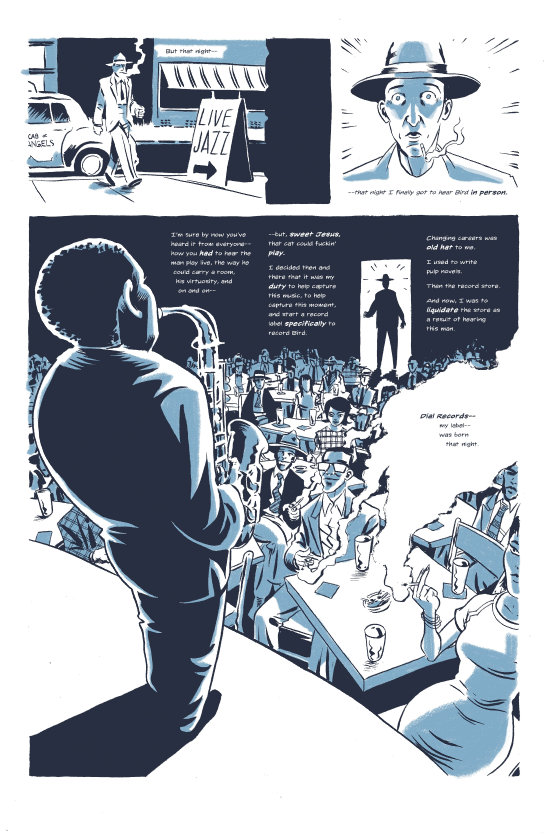

JJM You did a beautiful job representing and communicating Parker’s music and spirit artistically, and the colors you use are gorgeous. I was particularly drawn to the art in the chapter featuring Ross Russell [who recorded Parker], which has a distinct noir feel…

DC When COVID hit, Peter Markowski, the artist who did the colors for the first half of the book, had to focus on his job as an art director at Dreamworks Animation because the animation industry kicked into overdrive. Animators were actually able to work when virtually no one else in Hollywood could. Since he couldn’t finish coloring it I colored the John Coltrane chapter, the Ross Russell chapter, and the final chapter, “Outro.” The Russell chapter is interesting because he wrote pulp novels earlier in his life, and I wound up basing the visuals for the entire chapter on Richard Stark’s Parker: The Hunter, which is a graphic novel by Darwyn Cooke and whose work is similar to what I was going for in the chapter. There are not a lot of holding lines, and one single color is used. So that was a direct homage to Cooke, who is a major influence on me.

JJM One of the things that kept going through my head as I was reading this 140 page book is that virtually every page has multiple panels of complex, detailed and often symbolic art. You put so much effort into each of these panels, I am sure. What is your process? Is this all done by hand?

DC Yes, the art is by hand but not the lettering. I do the words digitally because it kind of facilitates my indecisiveness. I tend to be a very decisive artist, but with words I am in perpetual edit mode. I’m a visual thinker, so when I’m scripting it, I write it out like a movie script and would then send it off to the estate for approval a couple chapters at a time, and while I am typing I am also imagining what it will look like.

A page from the “Russell” chapter

It really helps to have a system. What I mean by that is if you will notice in the Ross Russell chapter the whole thing is built on four tiers of art, whereas in the Dizzy chapter, it is built on a three tier system. And then, how many panels do I allow myself to go wide on any page – is it three wide, is it four wide, is it two wide? In the [Parker’s girlfriend] Julie MacDonald chapter there are no panel borders, and if there are it is always a prop from another panel. For example, there is a scene in that chapter that talks about how bohemians were trying to live the change they wanted to see in the world, and that “borders weren’t needed anymore.” So I was trying to be a little clever, and on the nose about that. The William Claxton chapter is entirely built on a grid except for the one part where he drops Charlie off back at Charlie’s hotel, when the grid goes away and the art style changes.

As far as the art goes, there are varying numbers of thumbnails that I will do. For some of them I just thumb on the final board and for others I will thumbnail pretty heavily, it just depends on how complicated the shot is. I will also use a lot of reference photos that I will take of myself, or, as in the case of the Julie MacDonald chapter, a friend of my wife’s played the MacDonald character, so she came over and every shot is based on her. I knew the art style for that chapter was going to be less cartoony, more heavily photo-referenced. So the creative process changed from chapter to chapter in that regard. I purposely don’t time myself when I’m working, but I would say that I have a pretty high threshold for focus when I am working on this kind of stuff.

I finished the line art back on March, and I figure that between October and March I drew over six pages a week of line art, which felt crazy high. I don’t remember doing that much work, but I just get into a zone and time travel a little while I am working, and I really love the work. There was nothing about this project that wasn’t just totally thrilling and fun – every aspect of it was a joy.

JJM You finished this in March of 2020. In the book’s introduction, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar writes about George Floyd, which had to have been written no earlier than June. Your book does touch on racial issues in several different places. Were these already scripted into the book before George Floyd, or did you make any alterations to the story after his death?

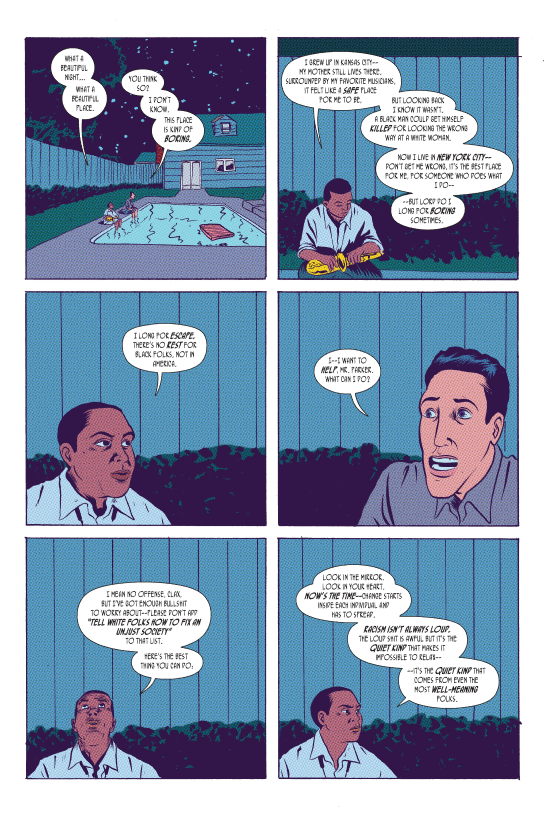

DC No, I didn’t make any alterations – that was part of the script from the beginning. Very early in the process, I understood that as a middle-class white man, I have blind spots. That’s inevitable. I don’t know what it’s like to be a Black person in America, so very early in the process I reached out to a Black music colleague of mine, Isaiah Smith, to talk through some things with him, and our lengthy phone conversation was really helpful. I sent him script pages along the way, and he became my sensitivity reader. Then there were other things that came from Charlie Parker – for example, the book by Robert Reisner includes a bunch of anecdotes about Bird by other Black people, which was also helpful.

Then it was like treating the book as an act of aggressive empathy because the thing I more clearly than ever understood is that it must have been exhausting as hell for Charlie Parker to live in America as a Black person, as it still must be for Black people to live in this white supremacist culture, where a target is on their backs all time. Charlie Parker very obviously possessed a supreme intellect in a society that was so awful to him, and if you look at all of his vices that were geared around escaping the confines of his mind – whether the vice was practicing his saxophone for 16 hours a day, or if it was heroin or sex or food – it had to be exhausting for him.

JJM Yes, and what is fascinating to me is how you communicate his complexities – which show up in virtually every chapter – not just in dialogue but with colors…

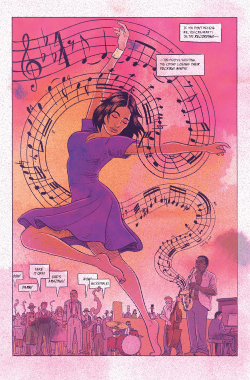

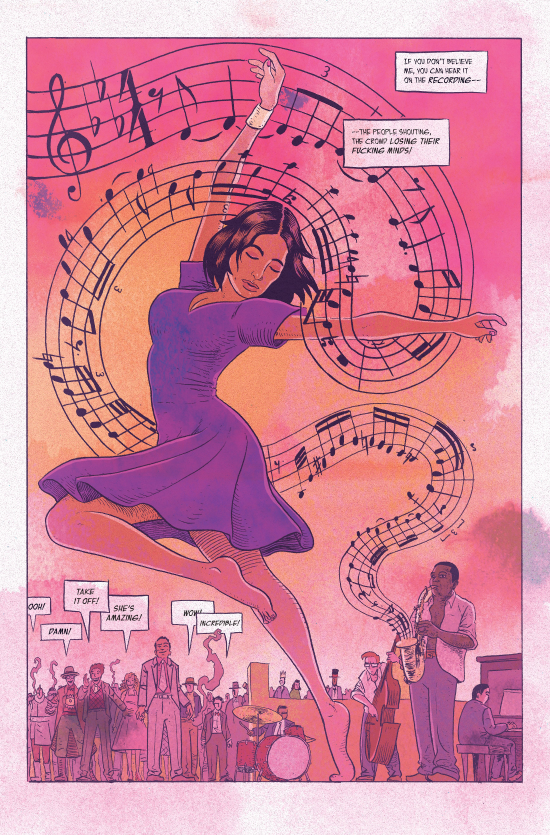

A page from the “Zorthian” chapter

DC I had a very strong vision for this book, which is one of the reasons I pushed to have Peter Markowski be the colorist. Color is a big part of storytelling, and from the outset we had long conversations about what the color for each chapter would be. One of the reasons I pushed for him is because he is an old friend and someone who I knew I could direct and provide with clear instructions about colors I was looking for in each chapter. That isn’t to say he didn’t bring his own genius to it – the only instruction I gave him for the Dizzy Gillespie chapter, for example, was that I wanted Charlie’s music to be pink, and I wanted Dizzy’s to be blue, and that everything else was up to him. So the sickly dark green color of the monster was his contribution, as was the overall complimentary color palette of magenta, pink, red, green, orange and blue. In addition, for the second chapter [a party held at the painter/sculptor Jirayr Zorthian’s house], the only instruction I gave him was that I wanted the colors to be really muted, and then as the party at the end of the chapter escalates, I wanted the colors to get more and more saturated and crazy. So that chapter lulls you into that sense of reading an old European comic with these muted colors, but when the party begins it suddenly feels like you just took two hits of acid.

JJM It felt like the 1960s to me…

DC Yes, reading about that party feels like the seeds of the counterculture. Who would have thought that in the late 1940s and early ‘50s there were parties where everyone is getting naked? Maybe I am being naïve but it seems like this was really wild stuff that felt more like the 1960s, yet it took place in the ’40s.

JJM Some terrific writers have taken Charlie Parker’s biography on – among them the revered jazz writers Stanley Crouch and Gary Giddins – but you are also dealing with material like Ross Russell’s book, which is notoriously inaccurate and controversial in the jazz world. So you have reliable and unreliable resources like these to turn to for details about your story. How did you merge the realities of his biography with the mythology, and what sort of artistic license did you allow yourself?

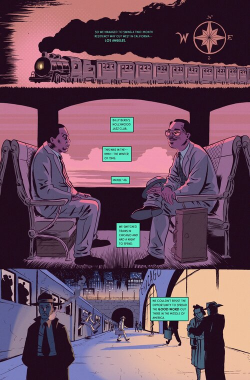

A page from the “Dizzy” chapter

DC I knowingly took some artistic license, and it was a bit of an anxiety of mine at times that maybe I am taking too much artistic license with this. For example, the opening scene in the Dizzy chapter has he and Parker on the train to Los Angeles, when in reality the entire band was on it. But I wanted this chapter to be just about those two, Dizzy and Bird – I didn’t want to muddy the water with having the other guys in the band, also on drugs, and also on the train. At one point during that trip Charlie gets off the train in Phoenix and ran off into the desert for some reason, and the drummer Stan Levey had to go get him and bring him back. This would have been a great scene but what would I have to get rid of to make room for it, and how much is that going to water down the depiction of this friendship between Dizzy and Parker?

Another example is that during the first conversation I had with the Parker estate management people they asked if I knew that Charlie was at a party in Los Angeles at the artist Zorthian’s house where everyone got naked while Charlie played. I knew about the party and was planning on including it in the book, but the thing is that the party happened after he was institutionalized, and the meeting with Claxton and Julie MacDonald happened after that also. So the entire framing device is me trying to make it a more satisfying reading experience rather than depicting the reality of the situation. I took a gamble on this and determined that if I rearranged this chronologically it wouldn’t wreck the story telling or make a dishonest representation of these events, it is just going to make for a more satisfying, overall narrative and framing device for the book, so I went with that. It was the biggest concession I made in terms of historical accuracy.

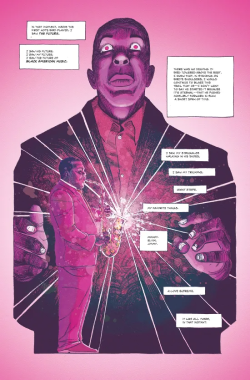

A page from the “Coltrane” chapter

.

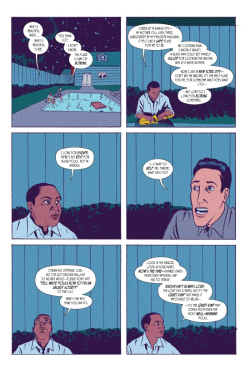

A page from the “MacDonald” chapter

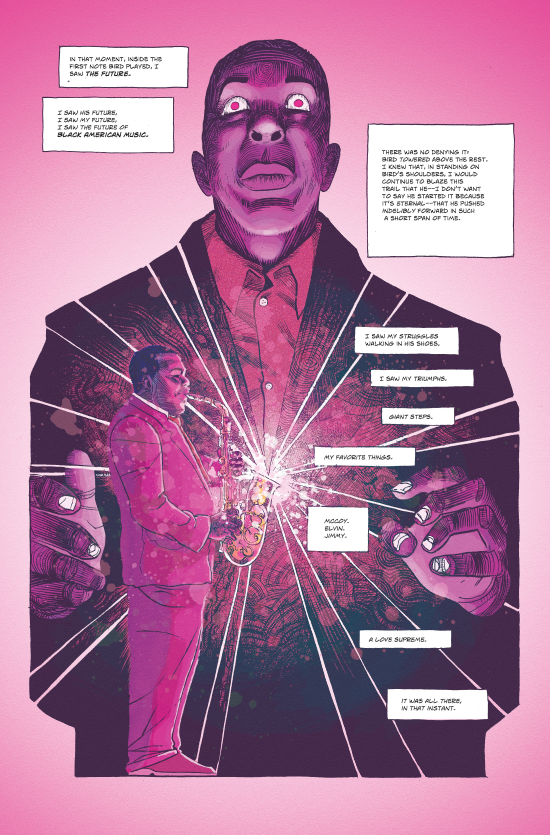

The other ones are more like taking a gram of information and expanding it into an entire chapter. The Coltrane chapter was built from a couple of sentences. I knew I wanted a chapter that was from the point of view of a younger saxophonist who sees Charlie Parker as this mythological figure, and when I found out that Coltrane played in a jam session in Los Angeles with Parker and Lester Young, I thought that this was obviously it, that Coltrane has to represent the saxophone playing world at that time. Some circumstances in the Julie MacDonald chapter are similar, where she describes something that happened between her and Parker in one sentence and I turn it into a full sequence. She says that Charlie was afraid of how angry he was – which is a really unique perspective you don’t get about Parker very often – and I felt that this needed to be expanded into a fight between the two of them. So that fight in my book isn’t documented, and his answering her pleas for attention and communication with musical quotes is just me trying to make something clever and entertaining.

JJM Right, it’s important to remind people that this is a novel – it is not meant to be an historically accurate account of his life. Another chapter in the book features the photographer William Claxton, and the narrative and art has a much different feel. The art was sunnier – some of the chapter took place poolside at Claxton’s parents’ suburban home – and Claxton and his white friends displayed a youthful interest in this Black genius who comes in from New York, impacting their lives that day…

A page from the “Claxton” chapter

DC Yes, this is another situation where when you are presented with an opportunity to write a graphic novel about Charlie Parker, you have a responsibility to write about certain things and present as full a picture as possible. I had to talk about the history of jazz music, which involves race and the Black experience, and I had to talk about drugs and do it in a way that was palatable and not exploitative. So, knowing that I had to talk about race, I needed for there to be a perspective from a naïve, young, white outsider representing someone who wants to help but doesn’t know how to, and may even be part of the problem but doesn’t realize it. As a white person in America this chapter is almost writing from my own point of view – someone who comes from privilege and who grew up idolizing Black musicians at every stage. I also knew that this conversation taking place in the Claxton chapter is much more contemporary than it would have been at the time. Realistically they were probably not going to talk about issues concerning race at that event, but I had to be responsible and I wanted to address this as much from my perspective as I can, so it made sense to put it in that chapter. I added the sunniness to the page because I wanted the chapter to feel a bit naïve, almost like an “Archie” comic.

JJM Yes, the style of art in that chapter is what I am familiar with from when I was a kid. The layout reminded me of Archie and Veronica. So that was by design then…

DC Yes.

JJM This book feels like a pioneering effort. Do you think other historical jazz figures like Miles Davis or Thelonious Monk will receive a similar treatment?

DC There have been graphic novels on Monk, Billie Holiday, John Coltrane, and another called Total Jazz by the French artist Blutch that is a bunch of vignettes. Without sounding too arrogant, what makes my book different from those are the credentials I bring. I am an educated, performing jazz musician, someone who has ten years of college and 20 years as a performer, and I think I get the small details right in the book, whereas a non-musician may not realize what they are getting wrong. And then the other aspects of attempting to depict music on the page are more successful or have a little more integrity in my book than in other books. So, if anything about my project is pioneering, it is that aspect of it. When you see notes coming out of Charlie’s horn in the Zorthian party chapter, those notes are a transcription of what he actually played on that recording, or when you look at the “Outro” bit, where Charlie plays and all those birds are flying, every two page spread is four measures of music, and the birds depict the contours and rhythms of the notes. That is my favorite part of the entire book.

JJM There is a lot to be said about your graphic novel being a way to welcome readers to jazz music, and to communicate the importance of someone like Parker and his connection to who we are now.

DC As I suggested before, it is hard for us with our 2020 ears to understand the revolution of Charlie Parker’s music, and what it sounded like to 1948 ears. It must have been mind-blowing to hear him live back then, and I wanted to put readers in that mind-blowing space visually in that last chapter, “Outro.” And that was my goal, to have it put people in a space where they are going to be wowed by this music that’s happening. Even if they are just looking at the pictures on the page, my intent was to provide them with this sense of awe people must have had from hearing Charlie Parker’s music for the first time. Even though he is just playing a 12 bar blues, it must have been incredible to hear.

.

.

___

.

.

A page from the book’s finale, “Outro”

.

“Bird preached the gospel of jazz. For him, it wasn’t just music, but a language that expressed the spectrum of being black in America: lively, dynamic, innovative, sorrowful, defiant. When we interact with jazz, it teases out of us who we are and projects who we want to be and compresses it then explodes it – all in an instant. A Big Bang of the soul.”

-Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, from the Foreward to Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California

.

.

Listen to Charlie Parker’s 1946 recording of “Yardbird Suite”

.

.

___

.

.

The following images are examples of pages within each of the book’s six chapters

.

.

A page from Chapter One, titled “Dizzy,” in which the complex friendship between Parker and Dizzy Gillespie is told

.

___

.

Chapter Two is titled “Zorthian” and tells the story of a legendary Los Angeles party Parker attended

.

___

.

In Chapter Three, Parker befriends the young photographer William Claxton, who invites him to his suburban Los Angeles home

.

___

.

Chapter Four is titled “MacDonald,” about an intense, short-lived relationship between Parker and Julie MacDonald

.

___

.

In “Coltrane,” the book’s fifth chapter, John Coltrane meets Charlie Parker

.

___

.

Chapter Six centers on the relationship with Ross Russell, the record executive who signs Bird to his label, Dial Records

.

.

___

.

.

Chasin’ the Bird: Charlie Parker in California

by Dave Chisholm (with Peter Markowski)

.

“Dave Chisholm, the writer and artist of this extraordinary new graphic novel, has crafted a penetrating work of biographical art that rejects the often reductive portrayal of a harrowed, joyless Bird in popular fiction and film.” – New York Times

Dave Chisholm is a trumpet player, cartoonist, composer, and educator currently residing in Rochester, NY where he received his doctorate in jazz trumpet from the Eastman School of Music in 2013. He coexists in both the music and comics worlds, resulting in a wide variety of creative projects. Additional comic/graphic novel works include psychological sci-fi series Canopus (Scout Comics, 2020), graphic novel + soundtrack Instrumental (Z2, 2017), as well as a variety of short stories for award-winning anthologies. He also teaches visual art, cartooning, and music at Rochester Institute of Technology, The College at Brockport (SUNY) and The Hochstein School in Rochester, NY.

davechishommusic.com

.

.

___

.

.

Great interview. I can not recommend this book highly enough. This was my introduction to Charlie Parker as a person and musician and to Dave Chisholm’s amazing art and words.

Here we are again, in similar circles! Though I suppose I have you to thank for introducing me to this graphic novel in the first place. But how did we both get to this interview?! Interesting…

Well, Aloha from Alaska! I was just telling someone from Vegas about your shop and about you the other day. Sorry I missed you when I was there in March: car troubles that prohibited us from doing much. I look forward to seeing you in the fall! Take care!

Oh, and I really enjoyed this interview and look into Chisolm’s process and inspiration.