.

.

photo by Kristin Emerson

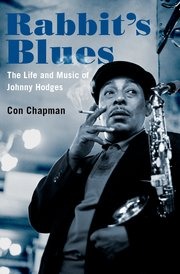

Con Chapman, author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press)

.

___

.

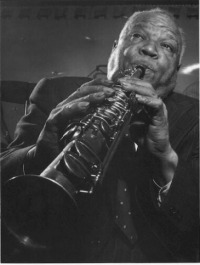

…..Who doesn’t recall their feelings upon first hearing Johnny Hodges? The rich warmth of his luscious tone was instantly memorable.

…..The emotional, succulent sound of his instrument floated from the speakers so luxuriously it could make even a staunch atheist imagine the existence of heaven. His music elicited wonder, cool, and passion.

…..In Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges, author Con Chapman writes that Hodges’s tone was so sensual that “the mesmerizing effect it had on female members of an audience was noted by multiple contemporaries: it was so seductive, according to one musician’s wife, that she told her husband ‘never to leave her alone with him’ because ‘whenever she heard [him] play she wanted to open up the bedroom door.'”

…..Duke Ellington – for whom Hodges played during much of his career – called Hodges’s tone “so beautiful it sometimes brought tears to my eyes.” Benny Goodman said that Hodges was “by far the greatest man on alto sax that I have ever heard.” Charlie Parker compared him to the operatic soprano Lily Pons. And John Coltrane considered Hodges his first model on the saxophone, even calling him “the world’s greatest saxophone player.”

…..That seductive and sensual tone Hodges is so well-known for is at the center of Chapman’s fine book – the first-ever biography of Hodges is a thorough, lively portrait of the enigmatic man and unforgettable musical titan.

…..Chapman talks about Hodges with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in this November 6, 2019 conversation.

.

.

___

.

.

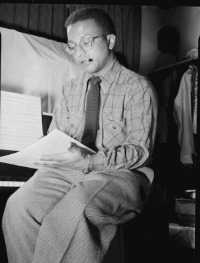

Photo by William Gottlieb*

Johnny Hodges (foreground) and Al Sears, Aquarium, New York, ca. Nov. 1946

.

…..“He was the Calvin Coolidge of the jazz world of his day, never saying three words when two would do. He was not an approachable person, rarely giving interviews and revealing little when he did; in the words of Stanley Dance, who got more out of him than any other writer, he ‘regarded his private life as private.’ Rex Stewart, a trumpeter in the Ellington band, said of him that ‘little of his personality emerged from the cocoon of his imperturbability.’ If, as Lytton Strachey wrote in Eminent Victorians, ‘ignorance is the first requisite of the historian,’ then the subject of this book provides the biographer with a fertile field to plow.

…..“But the taciturn figure he struck on and off the stage was diametrically at odds with the sounds — by turns languorous and inflamed — that he produced when he played. Despite the ambiguities concerning the mundane details of the nearly three score and three years of his life, he could be immediately and positively identified, then and now, by that most ephemeral of things: a single musical note, one of the few musicians in the history of jazz about whom that assertion can be made as anything more than hyperbole.”

-Con Chapman, from the prologue to Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges

.

.

Listen to Johnny Hodges play “Daydream,” from a December, 1961 recording session led by Billy Strayhorn

.

.

.

___

.

JJM I enjoyed spending time with your book, Con. Congratulations on your work, and thanks for joining me for this conversation. What is the genesis of your own interest in jazz music?

CC Well, I am old enough to remember when there actually was jazz music on AM radio. My dad was born in 1910, and my mom was born in 1917, so they were of the generation that had jazz in the house. While I had a rock band in high school, and my record collection included albums by bands like The Animals and The Byrds, at some point you get tired of the same old stuff and begin looking for something different. I am not qualified to play jazz but I listened to Wes Montgomery in high school, and when I got to college in the 1970s, I don’t know how I first picked out an Ellington album because he certainly was not in style at that time, but I began to pick out the voices in the orchestra that I liked, and the one I liked the best was Johnny Hodges. I went to college in Chicago and then came east and became friends with a lot of people who were sort of into older jazz, and it was then that I began to collect Johnny Hodges records, and some of the music he plays, even late in his career, just blew me away.

JJM Is this your first biography?

CC I have written a lot of books. My first book was a history of the 1978 Red Sox/Yankees pennant race called The Year of the Gerbil, and only Red Sox fans will know what that refers to. There was a generational divide on that team between the young, pot smoking players – mainly the pitchers – and the older generation represented by the manager, the fat old guy and lifelong baseball man Don Zimmer. One day a reporter asked Bill Lee, who was one of the pot heads, that if the Yankee manager Billy Martin is a rat, what animal is Don Zimmer? Lee responded by saying he is a gerbil – he is a big, fat, gerbil. This was the kind of conflict that was going on.

Ben Webster, Bengasi, Washington, D.C., ca. May 1946

JJM Why did you choose Johnny Hodges as your biographical subject?

CC I really liked his sound, and as you learn more about the Ellington orchestra, you pick out the musicians that you like, and while I really like Ben Webster, two biographies have already been written about him. I like Billy Strayhorn’s music, but there are already two biographies of him as well, and of course there are a number of biographies of Ellington. So I was left scratching my head and wondering why no one has written on Johnny Hodges. I got hip to the fact that Johnny is kind of out of style. Even when he was playing he got criticized for being too lush, and my reaction on hearing that was, you say that like it’s a bad thing – to me, that’s a good thing.

He was a musician who concentrated on tone as opposed to playing very fast. So, if you are going to put him up against Charlie Parker in terms of speed, obviously he is going to lose. If you put him up against Coltrane in terms of generating a new idea every four bars, he is going to lose that race, because that is not what he is into. So, I have to say that Johnny’s music and his progeny, especially Ben Webster, is the music that I listen to the most when I listen to jazz, and I listen very seriously to everyone from Jelly Roll Morton to some of the new music that is coming out now. But I always return to Johnny Hodges.

JJM Hodges died in 1970, and those who played with him and knew him are long gone. Were you able to find any new primary sources for your book?

CC As you can imagine, the book went through a thorough process of review – as it would with any academic publisher. There were at least six anonymous reviewers, and the question, “Why aren’t there any primary sources” came up more than once. First of all, he has been dead for fifty years. Second of all, he was a very closed-mouth person. Since the book has been published I have been contacted by three different people who said that they met him, and I asked each of them, “What did he say?” And, out of those three interviews, so far I have gotten five words – literally five words out of three people.

He didn’t like to talk, and he didn’t write stuff down. During my research, when I went down to the Smithsonian to go through the Ellington archives there, people said he was illiterate, but he was not. He did sign autographs, and he had two forms of hand writing, one was a cursive that was really beautiful. Back then, of course, when he went to school – he was born in 1907 – you learned cursive writing, and he had a really beautiful cursive signature, but he also wrote in block letters when he was writing a note to himself, or when he was going to label something.

Johnny Hodges (right) and Lawrence Brown, Turkish Embassy, c. 1930’s

So, after an entire day at the Ellington archives, going through boxes they had identified as having something related to him in them, I finally found on his lead sheet of “Darn that Dream,” he had written “get suit out of cleaners” in the margin. That is literally the only piece of writing that I found. I also contacted members of Ellington’s family and descendants of musicians in his orchestra, and basically nobody got back to me, and this is even through people who said that they would put me in touch with “so and so,” yet I never heard back from them.

One major discovery I came upon is a result of my lurking around on message boards of record sites, just to see what albums of his were available, and I saw a comment by a woman one day that said “Johnny was always good to my grandmother.” That just blew me away because it seemed as if I finally found someone who may know something about who he actually was, so I tracked her down. It isn’t easy to get to somebody who posts a message about a rare record on a record site, but I found her and she said that yes, she had actually done an oral history with a woman who Johnny had had a child by in high school, and if I can take credit for anything, it is tracking this woman down.

Regarding other sources, Johnny’s daughter by his second marriage was alive, and I literally hired two sets of private detectives – one in New York City and one further out – to try and contact her. They would go out to her house but there would be nobody there, and she wouldn’t respond to emails. I tracked down her husband on LinkedIn, but he didn’t respond. So, I think it is partly his personality – he didn’t talk much – but also, he may have burned some bridges with his family over the years.

JJM In addition to the daughter you mention here, he also had a son who died in his 30’s…

CC Yes he had a son, John, who actually played with Ellington on a couple of dates. He is on the CD, Everybody Loves Johnny Hodges, and he played on a couple of dates when one of the other Ellington drummers didn’t show up.

JJM How did Hodges become interested in playing the saxophone?

CC People who interviewed him said he started out on the drums, and then his mom made him take piano lessons, which he resisted and said he never got any good at it, but he was always able, throughout his career, to pick out and develop ideas on the piano. The story about why he switched is that he was walking by a store one day and saw a soprano saxophone he said looked so pretty that he just had to have it. So he went home and he asked his dad, who was a waiter and a porter, if he could get a saxophone, and his dad told him no, so he did what any boy does in that situation – he goes to his mom and asks if he can get this saxophone. She worked too – she cleaned houses and made about $3.50 a day – and she sort of “hemmed and hawed,” and he told her that if she didn’t buy it for him, he was going to turn to a life of crime and steal it. So she agreed.

JJM He took this playing on and was quite good at it, and quickly. His teacher, Bob Joiner, told him after a few lessons, “You’re finished taking lessons from me. How about teaching me a few things?” When did he begin to be seen as a “sensation?”

CC It is hard to find the records in the Boston area because while he was there he wasn’t associated with any big names. Back then, every hotel of any size and significance had a band on weekends that played in the ballroom, and there is an account of him sneaking into the back door of The Avery hotel and asking the band if he could sit in, which he did. Then he began to tour, playing resort towns in the summer when school was out, although he claimed not to have been a very diligent student and was truant a lot. There are records of him playing in Yorkville, Maine, and in Saratoga, New York when he must have been 17 or 18 years old, and at that time he played tea dances in Boston restaurants, which was a euphemism to get around the state’s blue laws.

.

A musical interlude…Sidney Bechet plays “Wild Cat Blues,” a 1923 recording

.

JJM An important early relationship you write about is Hodges’ with Sidney Bechet. You quote Hodges as saying, “He schooled me a whole lot,” and “if it hadn’t been for him I would probably be just playing for a hobby, not even professionally.” Talk a little about Bechet’s influence on Hodges?

CC The first and biggest influence was that he even heard Sidney Bechet’s record. This was really the beginning of the time when a musician wasn’t confined to what he heard in person locally. Johnny and his schoolboy friend and neighbor Harry Carney – later a band mate in Ellington’s orchestra – heard Sidney Bechet and Louis Armstrong on their records and absorbed the influence of New Orleans music. He was not a New Orleans musician, but he heard it over the radio and he heard it on these records.

Bechet would come through Boston and play there annually, even though, as Nat Hentoff points out in a book written much later, he didn’t like the city. Bechet was kind of a curiosity in Boston – he would come up from New Orleans and his appearance would be advertised as “Hot Jazz from New Orleans,” and he actually played in a floor show in the Black and White Review.

Sidney Bechet, Jimmy Ryan’s Club, New York, N.Y., ca. June 1947

How he met Bechet is not new history, although I tracked down a few more details than were previously reported. He would watch Sidney perform at this Black and White Review, which is basically a segregated vaudeville show, where the first act would be made up of white performers and the second act would be black performers. Eventually, he persuaded his sister Claretta – who was acquainted with Bechet – to introduce him. She took him backstage, and with him was his soprano sax, in the sleeve of a coat of his mother’s that she had ripped up for him to use as a carrying case. Claretta introduced him, and Bechet asked Johnny if he could play that horn, and Johnny played “Back in My Honey’s Lovin’ Arms,” and Sidney said “That’s nice.” It’s kind of funny because at the end of his life Johnny said that he was sick of answering questions about two people; Sidney Bechet and Charlie Parker, but everyone associates him with those two. Sidney was very much an egotist, and if you read his biography, he doesn’t say anything about Johnny – in fact, when somebody came up to Sidney once in France and said they liked how he played Johnny’s solo on “Sheik of Araby,” Bechet got mad and said, “He stole that from me!” So, while Sidney was a gigantic egotist who didn’t want anybody compared with him, the two did interact. One thing that Johnny learned from Sidney was how to play Sidney’s numbers, because he was in his band for a while in New York, and Sidney’s comment to Johnny was that “the old man” isn’t going to be here forever, so somebody’s got to learn this stuff.” They played a couple of duet numbers together, but mainly Johnny was there to be Sidney’s stand-in when he wanted to get a drink or go out with a woman.

JJM Before joining Ellington’s orchestra, Hodges played with Chick Webb, who he was very faithful to. It was challenging for him to leave Webb for Ellington…

CC People would say Chick and Johnny were cousins because they referred to each other as “cousin” in a familiar way, but they weren’t related, just very close, very simpatico. They were both short – Chick as a result of tuberculosis of the spine he got as a child – and they were both somewhat averse to written music. Chick’s band never had written arrangements, which was Johnny’s preference. The whole story of Chick is sad in some respects, but on the other hand he was a tremendous success for a while. His was the house band at the Savoy, “The Home of Happy Feet,” and they would basically cut every other band that came in for battles of the bands. But Chick also had a problem keeping his bands together; Ellington and Fletcher Henderson were both known for sort of using him as a farm team. One anecdote has Fletcher Henderson walking into the Savoy, and when Chick sees him asks Henderson “Well, which one of my men did you want now?”

For whatever reason, he couldn’t keep his band busy. He was a bit of a perfectionist and didn’t want to break up his band into different combinations, so he didn’t get all the jobs he needed to keep the band together. So, in a lot of respects it was a tough decision when Duke asked Johnny if he would like to join the band, and Chick eventually told Johnny to go ahead, you will do better with Duke because you will get more chances to solo.

Chick Webb’s band was known for very tight ensemble playing and they would literally rehearse, not from the score, but Chick is sitting there telling his musicians, “Ok, you go da da da da da, and you go da da da” and they would memorize these things – they were completely from the head. As for why Johnny resisted Duke’s overtures for so long, Duke probably asked him three of four times, but the Ellington band was a reading band, they had scores, which is one reason why Ellington kept the band together so long and his music survives. He developed a big book of songs that generated publishing revenues from sheet music as well as recordings, but it meant musicians had to be able to read music. Johnny had some training, and he had some lessons. He was a slow reader, but once he knew what a page of sheet music sounded like he could handle it.

.

A musical interlude…Duke Ellington plays “Diga Diga Doo,” a 1928 recording

.

.

JJM Johnny’s first gig with Ellington was at the Cotton Club in 1928, and his first recording session was in June of that same year. What were the first songs he recorded that are available for readers to access?

CC There are early collections, but some have gone out of print, and when they came back into print, unfortunately, they did so in a much more expensive format. The Mosaic box sets have a lot of the early Ellington on them, and there used to be some RCA reissues of the old Vintage Series, which has some great early Ellington. You can hear some of it on YouTube, for example, “Diga Diga Doo,” when Ellington was incorporating music from the Cotton Club floor shows into his repertoire, and that stuff is still hot.

JJM Hodges was, as one intimate of the two men put it, “rude” to Ellington “time and time again,” and a reason is that, while Hodges was responsible for some of the orchestra’s most recognized sounds, it was Ellington as leader of the band who profited most from them. Talk a little about their relationship?

Duke Ellington, New York, 1943

CC Well, two things. Number one, as with every professional organization, part of the issue was money, and Johnny was not as sophisticated as Duke was. Duke was under the tutelage of Irving Mills and learned a lot about the music business, one of which was that in order to make money, the band would have to keep creating content. You can’t just record the hits of the day because then you only get half of the royalty revenue. In his early days, as Mercer Ellington reported, Johnny would sell a riff to Duke for $100 or $200 and give up all his rights, and then Duke would take it and fashion it into a hit. The other issue was that while he was creating all these beautiful, romantic and sensuous sounds – so sensuous that one of his band mate’s wives told her husband not leave her alone with Johnny because she would get into bed with him – Duke was sleeping with them, not him.

JJM His tone was indeed sensuous, and you could pick it out from every saxophonist in the world. What was the genesis of his tone, and how did he create this unique sound?

CC Rex Stewart, the trumpeter in Ellington’s band who also wrote two books, said that Johnny’s sound could never be duplicated. I think tone has to do with how big and how tall you are, and your mouth, your lips, your embouchure. There is a difference between an amplified instrument like a guitar and an unamplified instrument like a saxophone. A guitar amplifier’s control settings can be set in such a way that two people plucking the same note or the same string are likely to produce a similar sound. There is a greater level of agency involved in playing an unamplified instrument, it means that it is closer to an individual’s makeup, and from the very first, people said, wow, you can really play that thing, and you create this unique sound. Some guys get on the alto and maybe it’s because they don’t breathe deeply enough or they may not hold their notes long enough, but they don’t create the warm, round, bell-like sound that Johnny did. I compare it to Clifford Brown sometimes on the trumpet – it’s like they both had a certain physical makeup, and when a person that size with that embouchure plays an instrument, that’s what comes out.

JJM You write that Hodges was an “inadvertent translator of the glissando technique to American jazz.” What was his explanation for how that happened?

CC. He said it happened almost by accident. One day he was playing “Passion Flower,” which was one of his big ballad numbers with the band, and toward the end of the day he was tired and when hitting a high note he said that he just sort of let it slide rather than ending it abruptly at the end of the solo. And if you look at a YouTube clip of him playing, you will see him move the saxophone from the center of his mouth when he’s blowing, to the side of his mouth, almost as if he is talking out of the side of his mouth when he creates that glissando. He became known for this and it truly was unique.

Before Johnny, the glissando was thought to be impossible on the saxophone, and it was also considered to be in bad taste, amazingly enough. The best way to explain it is that it was too erotic. This is true in western European classical music generally – you don’t hear the glissando a lot in the Boston Symphony Orchestra – but making that sound is not considered inappropriate in non-western cultures.

.

A musical interlude…Johnny Hodges plays “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be,” recorded c. 1940

.

.

JJM You write in your book about some of the sessions Hodges recorded outside of Ellington’s orchestra. Which of them stand out for you?

CC I would start at the beginning, with the sessions he did with Teddy Wilson and Billie Holiday. I don’t think anybody thought at the time that those three would turn out to be the classic musicians that they did. At the time, Johnny was probably the most famous of the three. Teddy Wilson was certainly known, but he was not as well-known as he would be once he began to play with Benny Goodman’s trio and quartet. So, that’s a good place to start. In terms of the stuff he did with other people, Blues Summit – which is a combination of the Back to Back and Side to Side records that he did with Duke – is a great album. Those are actually not made up totally of Ellington units, they also include some Basie musicians, and Roy Eldridge is on them. I think they shook up the rut that Johnny and Duke had fallen into. Those are my favorites, recorded in 1960, and they have never been out of print.

JJM Johnny Hodges was in the discussion of being the greatest living saxophone player during a time when the likes of Ben Webster, Charlie Parker, and John Coltrane were in their prime. Coltrane once referred to him as the greatest saxophonist alive. Another great saxophonist who was a bit of a rival was Benny Carter…

CC Yes, the first time Johnny heard Benny Carter he told a friend to go out and hear this guy play, that he is the greatest alto saxophonist in the world. His friend was classically trained and played some symphonic gigs in Boston, and when he went to New York to hear Carter play for the first time he didn’t think he was that great, but he revised his opinion after hearing him for the second time.

Benny Carter, Apollo Theatre, New York, ca. Oct. 1946

There is a really sharp contrast between the two. Benny Carter was largely self-taught, but he is kind of a “polymath.” He learned several instruments, including trumpet, he learned a lot about harmony, and he eventually became a very sought after arranger, so he was able to do what Johnny did not, which was to develop a career outside of the Ellington band on his own. Carter was a very active Hollywood session player and arranger, and it was all because he had taken an intellectual approach which Johnny always sort of denigrated – like he would say, don’t give me too much music, let me “go by myself,” which you’ll hear older jazz musicians like Alberta Hunter say when they mean “improvise.”

After that early starting point – when Johnny called Carter the greatest alto saxophonist in the world – they became rivals, and there are a couple of reported instances of conflict and controversy between them. One was at a Newport Jazz Festival, where Benny was going to jam with the Ellington group, and Ellington, as he often did, put Carter in a position where he did not come off favorably as opposed to Johnny. He would say that they were going to play “my numbers,” meaning Ellington numbers, which Benny sort of knew but sort of didn’t. You have to think that Carter was hoping they would play a standard that everyone knew. That session ended unhappily and in confusion, but Benny Carter, being the consummate professional and gentleman, didn’t say anything about it. In another instance, Duke actually hired Benny to replace a musician who had to take time off to attend a funeral, and it is reported that when Benny showed up, Johnny just grunted at him and turned away. But, at the end of their life, when Benny learned that Johnny had died, he wrote a very sentimental piece as a tribute to him, so despite the sparring they may have done over the years, they respected each other. Each one is different – one is the cool Apollonian, and the other is the hot Dionysian.

JJM Hodges left Ellington’s band in 1948, and Norman Granz played a significant role in his decision to do so.

CC Promoters and record producers like Granz figured out that since they didn’t represent the Ellington band, it might be to their advantage to snag a soloist from it and record them independently. Basically Granz rode on the bigger wave that the Ellington band created, and he was very much the agent provocateur. He went to Johnny and told him that he was not being recorded to his best advantage, and that he was not getting enough solo time – which is bunk, basically, because Johnny took more solos than anybody in the band by a factor of three to one for a lot of years. But he persuaded Johnny to leave, and he also persuaded Lawrence Brown to leave, and they set up this combo.

Norman Granz, c. 1947

Granz was a professional, and he was one of the few guys who actually figured out how to make money recording and promoting jazz, and he got his musicians a lot of work. But Johnny found out – as many great soloists who think they can become a band leader have – that there’s a difference between being the top saxophonist in the band and being the leader. The leader gets more money because he is keeping the band together and the business coming in while the soloist plays and gets the applause lines, thinking they can become leader. Johnny didn’t have the personality for that. Duke was a master at it, great at introducing songs and soloists, always ending his concerts with “We Love You Madly,” whereas Johnny was not. I found one review of a concert of Johnny’s that said “this band could really profit from having a hypodermic needle stuck in it.” Johnny apparently didn’t even introduce the songs and had his back turned to the audience at times. He didn’t care, he just wanted to play his stuff. But he was always pleasant about it – it’s just that he wasn’t an outgoing person.

JJM In addition to Granz having influence on Johnny’s decision to leave Ellington, another reason is that he didn’t like Ellington’s tone poems, and wanted more simplicity in his performances…

CC That’s right. There are a couple of anecdotes about that. One example is a time they bought an arrangement from Teo Macero that was very modern and complex, and in the middle of rehearsing it, Johnny stood up and tore his sheet music in half. He refused to play it, and the band never played it again.

And, when Johnny left the band, his group was playing easy blues, and even had a hit called “Castle Rock” that was one of the earliest songs to be identified as a rock and roll song. They played dances and concerts in night clubs, and you can get a pretty good idea about their itinerary during this time by going through the history of John Coltrane, who played with Johnny for almost two years. This group was not playing the sophisticated, high minded stuff that Ellington aspired to – they were playing dance music. You can like both of them, which I do – I like a lot of the Ellington suites – but Johnny was a guy who grew up listening to Sidney Bechet, the New Orleans musician who as a badge of pride would say, “I don’t know how to read music.” And Sidney Bechet never did learn to read music because he thought it would stifle his capacity for improvisation, and Johnny was from the same school, which was taking a stand on what he was willing to play.

He would work with Billy Strayhorn, who wrote a number of ballads with Johnny in mind as a soloist, and they would get together beforehand and Johnny would tell him that what he was asking him to do was hard – that he couldn’t play “this note” followed by “that note.” Billy just didn’t know the saxophone fingering or whatever, so he would change it, but I don’t think Ellington did that. When Ellington had a tone poem or one of his suites in mind, he wrote it and Johnny played it.

JJM You describe Hodges as becoming, “Strayhorn’s instrumental soloist of choice,” who worked with Hodges on bringing a side of himself out that hadn’t really been exposed before…

Billy Strayhorn, c. 1946 – 1948

CC Well, he was certainly the soloist of choice on the ballads once Ben Webster left the band, but those are very much the Ellington numbers, and say what you will about Ellington and Strayhorn, they were a great combination. They did generate different kinds of music. Strayhorn wrote “Lush Life” – is there anything in the Ellington book before Strayhorn that has the same sort of melancholy side to it? I don’t think so, and that is what Strayhorn brought to the Ellington band, an undercurrent of sadness that had been driven out of the Ellington book. If you listen to “East St. Louis Toodle-oo,” for example, it has a bridge that is sort of upbeat. It starts out with a dirge, and then it turns into this upbeat thing – and Billy didn’t do that. He wasn’t writing for an audience dancing, or for an audience in a night club, he was writing truly symphonic music. He had the opportunity to get harmonic training at the college level, an opportunity he really created for himself.

Duke, of course, hit the road early. He had a chance to go to Pratt Institute in New York to become an artist, but he became successful so early that he just took off and picked things up on the fly. There is a famous anecdote where Percy Grainger has Duke come into his class at NYU and has him play a few things on piano, and Grainger said, “That sounds very much like Delius,” and Ellington said, “I don’t know much about this Delius fellow, I will have to find out who he is.” So he and Strayhorn were very different, and it is interesting that, on the one hand, Johnny said “I don’t like the tone poems,” but on the other hand, he and Strayhorn worked together sort of behind Duke’s back and created this beautiful art.

.

A musical interlude…Johnny Hodges plays “Misty” with Lawrence Welk, recorded in 1966

.

JJM You wrote about Johnny’s recording he made with Lawrence Welk – hardly the picture of “hip” – and how Welk tried to hire him for his orchestra…

CC The first time I saw that album – in a used record store – I almost had a heart attack. It’s like finding out that your favorite movie star has a pet goat that he has sex with. How is he playing with this guy? But they hired the best arrangers, including Benny Carter, and I have to say that when you put the album on and listen to it – taking into account the fact that it’s an older record and compare it to other albums with strings – there is really nothing wrong with it.

Welk was always trying to lure Johnny away because he loved his sound. He offered him a full time position on several occasions, and it would have been great for Johnny. In an interview in England toward the end of his life, Johnny said that had he gone to work for Welk, he could have had a life of making albums that would take him about three days in the studio, be in a TV show that takes a couple of weeks, then he could relax, compose some stuff, and he could live an easy life that wouldn’t have him on the road all the time. But he turned it down. A lot of people left big bands for their own reasons, usually because they got tired of life on the road, and Johnny had a chance several times over his career to have an easier life, but he said, you know, I have been playing Duke’s music for so long, I am going to stick with it.

JJM Did he appear on the TV show with Welk?

CC I don’t believe he was ever on Welk’s show, but when he broke his group broke up he began to play on The Ted Steele Show, which was a regional show in the New York/New Jersey area. It was very successful – kind of like Lawrence Welk, but on a regional basis. And Steele was not an unhip guy like Welk was, in fact, he was a reputable jazz figure who always hired good musicians. He sort of drew the line at bebop, and became the ultimate anti-bebop crusader, saying that bebop was debauching the youth of America, and wouldn’t allow anyone to play bebop on his show. But Johnny said it was a decent gig. The show would feature talk and live music, and Johnny would play two numbers – a ballad and an upbeat number – but as Johnny said, he was playing for all these little housewives in New Jersey and got kind of stale and getting tired of it.

I think Johnny was too proud to go back to Duke with his tail between his legs, so his wife actually made the overture to Duke about his return. She called him up and asked Duke if he could use another alto, and of course Duke knew exactly what she meant and told her that Johnny could come back any time. So, that was the end of his solo career. It came at a low point for Ellington too because at that point big band music was kind of square. The smaller combos and soloists had taken over…

JJM This was right after Charlie Parker died, right?

CC Yes. Things had gotten so bad that the Ellington band – what we now view as probably the greatest jazz orchestra in American history – was playing on Elliott Murphy’s “Aquashow,” where there would be dancing fountains and sprays of water and people doing fancy dives into hoops of fire, and Ellington was basically providing the background music.

Then they got invited to do the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956, and they weren’t even the headliner there. They had a split shift, which, if you have ever been a waiter in a restaurant you know what that is; you work lunch, then you have three hours off, and you come back for dinner – it’s terrible. So Ellington complained to the festival promoter George Wein, and said, “What are we, the animal act? Why are we sitting around all day?” Of course, the rest is history, which is, for whatever reason, they began to play “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,” which they had played a number of times in a variety of ways, but they had developed this one rendition where Duke opened it up and then Paul Gonsalves took over and soloed. While the band played, a woman got up and started to dance, which was almost unheard of at a jazz festival, and the crowd got restless as the band kept playing, and more people get up and dance, and all of a sudden Wein practically had a “Woodstock” on his hands. He made signs to Ellington to “cut it off” – he didn’t want a riot. Of course, Ellington wasn’t going to get off the surfboard while riding the wave, and he shook his head and the band kept going. There had been an article on Duke for Time magazine in the pipeline for a while, and after Newport it became the issue’s cover story. All of a sudden, Duke has a new contract with Columbia, which was quite lucrative for a big band at the end of the big band era.

JJM Yes, Duke said he was bored before Newport in 1956…

CC Yes, and Newport came at a time when he was very low, and the success there gave him the freedom to record the ambitious stuff, plus he had Johnny Hodges back.

Duke Ellington, Washington, D.C. (c. 1938 – 1948)

JJM Hodges died a couple of years before Ellington, and you write that Hodges’ death had a deep impact on Ellington…

CC Yes, Johnny’s death came at a very sensitive moment because they were in New Orleans at the time, recording the New Orleans Suite, which was to include a portrait of Sidney Bechet in it. Johnny had actually stopped playing soprano saxophone for the Ellington orchestra, which was an issue about money and artistry – artistry in the sense that Johnny always said the soprano sax is tough, you can’t just play it as a second instrument, you have to play it all the time. He also became aware of the fact that under the musicians’ union rules, if he played two instruments he was entitled to a bonus. So he told Duke that if he wanted him to play soprano, he would have to be paid more. Duke could be pretty tight with a nickel, and said that he will just write the soprano parts out. But when Duke decided to do a tribute to Sidney Bechet, he wanted Johnny to play soprano again, which he knew was a sore subject with him. Mercer Ellington was dispatched to pitch it to Johnny, and Johnny said he was going to stand on his rights, that if he plays soprano he would be entitled to extra pay. When Mercer came back to his father and told him this, Duke said “Pay him whatever he wants.” Unfortunately, Johnny died in his dentist’s office, so that circle of him coming back and playing Bechet was never completed, which is sad because here they were going to resolve this lingering argument that they had but were unable to.

JJM How would you describe Johnny Hodges’ musical legacy?

CC Well, I have to say that he has been out of fashion. If you were to walk into a bar in Boston, where he grew up, and ask people who the greatest blues man Boston ever produced is, I am sorry to say the answer would probably be a member of Aerosmith or the J. Geils Band. But, leaving aside the fact that rock has displaced jazz as America’s popular music, where does he rank in the pantheon of jazz greats? I think Johnny’s lesson, which has somewhat been forgotten, is that people want to hear beautiful music, which is what Johnny was most interested in. Not the fastest or most complex necessarily, just–beautiful.

It’s kind of funny because here was this little guy, five feet five inches tall, kind of gruff, not easy to get along with, who wouldn’t even get into a conversation with you, yet when he put the horn to his lips, he poured out pure beauty.

.

___

.

“Johnny Hodges,” a painting by James Brewer

“In his essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ T.S. Eliot observed that we praise an artist for ‘those aspects of his work in which he least resembles anyone else,’ but the most original parts may be those in which his ancestors ‘assert their immortality most vigorously.’ If Johnny Hodges’s like is not found among us today, it is because he was that rarest of things — a true original, in a grand tradition.”

-Con Chapman

.

.

_____

.

.

PASSION FLOWER

After The Duke’s quietly rippling, opening statement, such passion

in that flower as it opens to a world of unsuspecting listeners,

and Johnny Hodges sings in purest of alto sax voices a long limpid line,

elegantly phrased, a lovely horn grown flower of ineffable beauty

rising inevitably to bluest of deep blue skies, a musical flower

bestowing benediction on all within hearing, casually bequeathed,

with a look that suggests you don’t truly understand what you are

being given, and the tone soars, then whispers, always pure, always

silky, always creamy, and the world for a few minutes grows more

beautiful, listeners float in a river of perfection, then all who hear

are diminished as all becomes once again ordinary, as the last perfect

note drops into silence, and Hodges disappears from behind the microphone,

and all is silence, all is routine, the quotidian coats life with blandness,

and all who heard the musical marvel that was Johnny Hodges play, pray

that memory will retain what was heard and bear witness that beauty can exist.

.

.

.Watch Hodges play “Passion Flower,” Jan. 1967 (from “Jazz Video Guy” You Tube channel)

.

_____

.

.

Listen to Johnny Hodges play “Jeeps Blues,” with the Duke Ellington Orchestra, recorded live at Newport, 1956

.

.

.

___

.

.

Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press)

by Con Chapman

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Kristin Emerson

Con Chapman’s work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Boston Globe and The Christian Science Monitor, and his writings on jazz have appeared in The American Bystander, The Boston Herald, and Brilliant Corners. He is the author of two novels, thirty-two stage plays, fifty books of humor, and The Year of the Gerbil, a history of the 1978 Red Sox-Yankees pennant race

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on November 6, 2019, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Thomas Brothers, author of Help! The Beatles, Duke Ellington and the Magic of Collaboration

.

.

*All photos by William Gottlieb are from the William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, (Library of Congress)

*Photo by Gordon Parks/Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information photograph collection (Library of Congress)

Painting of Johnny Hodges courtesy James Brewer

Michael L. Newell is a retired teacher who recently moved to Florida. He tries to write poetry from time to time

.

.

.

Michael: Absolutely one of your best and most powerful. You really captured it here!!!!!

I liked the lines …”the tone soars, then whispers, always pure, always silky, always creamy.”

On purpose he could fade in and out so well … Great break in the last lines, “beauty can /

exist.”I am not over doing it here. Michael you really have this down here.!!!!!