.

.

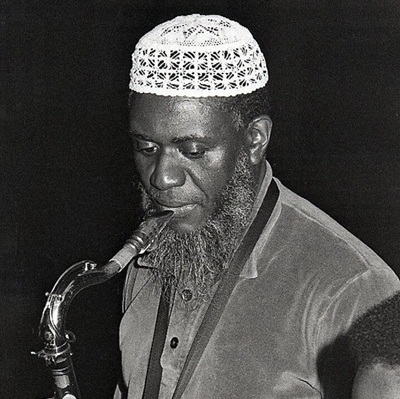

photo by Jahsie Ault

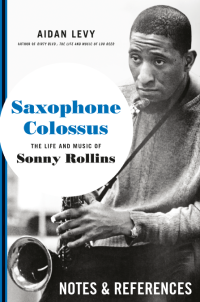

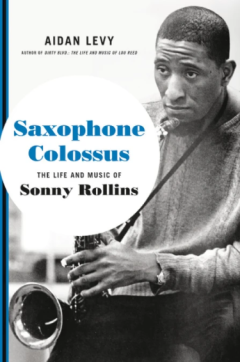

Aidan Levy, author of Saxophone Colossus, the Life and Music of Sonny Rollins [Hatchette Books]

.

.

___

.

.

…..In his exceptional new book, Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins, the author Aidan Levy appropriately describes his subject as “one of the greatest jazz improvisers of all time,” a “bridge from bebop to the avant-garde,” and “a lasting link to the golden age of jazz.”

…..Rollins’ musical contributions to the world of jazz over seven decades are well-known, but this book – with the cooperation of Rollins himself – fills in his somewhat elusive backstage biography, including his relationships with fellow jazz giants like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Clifford Brown, and Max Roach; the making of so many iconic albums – Tenor Madness, Freedom Suite, and Saxophone Colossus among them; his experience with America’s criminal justice system and how he beat his drug addiction; and how he used jazz to advance the civil rights movement.

…..Levy is a gifted writer who has meticulously researched his legendary subject. His book is essential, passionate, memorable…and highly recommended. He discusses Rollins and his book in this November 14, 2022 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita.

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Brian McMillen/CC BY-SA 3.0

Sonny Rollins at San Francisco Opera House, 1981

.

“Jazz is life as shown through music. Jazz is life in musical form. Jazz is the musical expression of life. As we all know life changes every second. Each snowflake that falls is different. Every sunset is different. Every surprise is different. The clouds in the sky are never the same – always changing. Jazz mimics life.”

-Sonny Rollins

.

“His rhythmic concept and his sense of humor, his intensity, his sound, his romantic touch in his playing, when he’s playing a ballad or something, he has all the expressions of life.”

-saxophonist Jimmy Heath

.

.

Listen to the 1956 recording of Sonny Rollins playing “You Don’t Know What Love Is” (from the album Saxophone Colossus), featuring Tommy Flanagan (piano); Doug Watkins (bass); and Max Roach (drums). [Universal Music Group]

.

.

JJM Why did you decide to write this book, Aidan?

AL I’ve always been a fan of Sonny’s music. In 2012, I did an interview with him for the first time for Blue Note Records Spotlight, and after spending an hour talking to him on the phone, I was so enlightened by the conversation that I began looking deeper into his biography and into his music than I ever had before.

I read every book on Sonny; among others, Saxophone Colossus: A Portrait of Sonny Rollins, the beautiful photo book by John Abbott with accompanying essays by Bob Blumenthal, one of the greatest jazz critics; Eric Nisenson’s Open Sky: Sonny Rollins and His World of Improvisation; Peter Niklas Wilson’s Sonny Rollins: The Definitive Musical Guide; and Richard Palmer’s Sonny Rollins: The Cutting Edge. For a more technical perspective, there is the brilliant trombonist and educator David Baker’s The Jazz Style of Sonny Rollins. Then there are the documentaries, including Robert Mugge’s Saxophone Colossus and Dick Fontaine’s Sonny Rollins: Beyond the Notes, both essential viewing. All of these are excellent, but I was hoping to read a more comprehensive account of his life and music, so at some point I decided to try to do it myself. Also, the first jazz album I ever bought with my own money was Sonny Rollins’ Saxophone Colossus, so, I’ve been listening to him since I began playing the saxophone, and I wanted to know more.

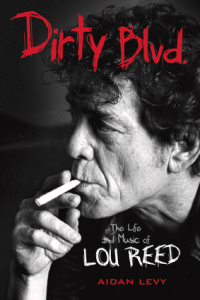

JJM You wrote a biography of the rock musician Lou Reed prior to this book. How did that prepare you for writing a biography of a legendary jazz musician?

Levy’s Dirty Blvd: The Life and Music of Lou Reed [Chicago Review Press]

AL Working on the biography of Lou Reed helped give me a sense of how to do biographical research – for example, how to immerse myself in what has been preserved in libraries in a way that illuminates details of a musician’s life that are not part of the historical record, in other words, not what you would find on Wikipedia. In addition to that, conducting interviews with the musicians and other associates in Lou Reed’s life helped me tell a story I felt had not been told before.

Beyond that, a lot of what went into this book on Sonny Rollins came more from my involvement with the jazz community as a journalist, and also through the Columbia Center for Jazz Studies, which I’ve been involved with for close to a decade now. So, while there’s not necessarily a straight line going from Lou Reed to Sonny Rollins, I can say that there are some points of connection. For instance, they both worked with the trumpeter Don Cherry, and I can also tell you that Lou Reed skipped part of the release party for the reunion album with the Velvet Underground to attend a Sonny Rollins concert.

JJM Oh, really? That’s a funny connection…

AL Yeah. So, the simple truth about why I would move from writing a book about a rock star like Lou Reed to one on Sonny Rollins is that I love their music. When I set out to do these projects I was of course aware of the fact that they’re not in the same genre, but I’m a listener, and I listen beyond genre categories. But I’ve always been a jazz fan and musician first and foremost, and writing this book on Sonny has been a life changing experience.

JJM Was Sonny himself a major source for this book?

photo by Bengt Nyman/CC BY 2.0

Sonny Rollins at the Stockholm Jazz Fest, 2009

AL Yes. Before I began research, I contacted Sonny to let him know I was hoping to write this book and to get his approval since I was not intending to move forward with the project if he wanted no involvement in it. I was surprised to find out that he said “OK” at the time, which was in 2015. From there we spoke over the phone many times during the course of my research, and after I finished the first draft of the manuscript, I sent it to him so we could go through it together. I don’t believe he wanted to read an entire book about himself, but we were able to go through it to the point where he made comments and additions that were incorporated into the final draft.

JJM Sonny kept a journal. Did you have access to that?

AL Sonny’s archives are held by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which is part of the New York Public Library, and which is located two blocks from where Sonny was born. Anyone with a New York Public Library card can find Sonny’s writings, including his journal entries on yellow legal pads, his practice notes, and his correspondence. It is more extensive than almost any jazz archive I’ve ever seen. We are all indebted to James Goldwasser and Matt Snyder, who worked on processing this archive at different stages, as well as literary agent Chris Calhoun and the entire staff of the Schomburg. So, it turns out that Sonny was writing all the time, and his writings – along with his business records – have been preserved in that archive. He kept track of his process and his personal growth and development in a way that many of us have always aspired to, but it can be hard to maintain a strict regimen of journaling. Sonny, on the other hand, always seemed to be making notes of what he was working on.

I did find documentation of his process in the archive, but piecing it together was not always easy since not every entry was dated, but there was usually enough context in the document to date it. So, he wrote a lot and the Schomburg Center was one of the main pillars of my research for the book. I was excited to get in there. When I started doing research I knew the archive would be available, I just wasn’t sure when. I must have been the first person or one of the first in there to look at this material.

JJM What was Sonny’s primary form of musical training?

photo courtesy of the author

Sonny Rollins at approximately sixteen years old

AL Sonny did take music lessons. When he was young he went to a school called the New York Schools of Music, where lessons would cost a quarter. Part of the idea of this school was to democratize music instruction. The school had branches all over the city, one of which was in Harlem, where Sonny got lessons from a reed player named Mr. Bastien. Since the school was vehemently opposed to jazz – the founder of the school had a public dispute with Duke Ellington about the value and significance of jazz as an art form – the lessons were in classical technique. Sonny then had several other teachers, one of whom was Joe Napoleon, the brother of pianist Marty Napoleon. Joe was a legendary teacher, and many people studied either with him or Joe Allard. He was one of the first to give formal lessons towards becoming a jazz musician, and one of the things that he worked on primarily with Sonny was tone production. Sonny is known for having maybe the biggest sound on tenor saxophone in the history of jazz, and I think it started in these lessons with Joe Napoleon. The other instructor he had was named Walter “Foots” Thomas, a musician who was also the former musical director for Cab Calloway’s band, but as he got tired of life on the road, he opened up a studio and began offering music lessons. These lessons would be advertised in Down Beat magazine – I found one ad for lessons with Thomas right on top of one for Joe Napoleon, so you can connect the dots there. Thomas also taught jazz theory, and he believed that you could formalize the fundamentals of improvisation. So, Sonny began learning about how to navigate chord progressions with Thomas.

Other than that, Sonny was an autodidact who learned on the bandstand in clubs like the Club 845 in the Bronx, at Minton’s and all over Sugar Hill and throughout Harlem. He also learned by playing records repeatedly by Charlie Parker and Don Byas, for instance, absorbing that material. But largely I would say he learned in the clubs and from playing sessions with his peers at local churches and dances.

JJM Where does his legendary work ethic come from?

photo courtesy of the author

Sonny Rollins (left) with one version of his early band, the Counts of Bop, formed with friends. (Musicians unidentified)

AL It’s tough to say where it comes from, but I think that, in part, his family instilled that in him. Everyone in his family worked hard. His grandmother Miriam was a Garvey-ite activist and he would attend marches with her in Harlem where she would advocate for Paul Robeson or the Scottsboro Boys. His mother was also a hard worker – she worked as a domestic in Harlem, and would sometimes take Sonny to work with her. And Sonny’s father Walter worked all the time as a chief steward in the Navy. His older brother Valdemar was known in the community to be a hard worker and a scholar, and his sister Gloria as well. And while I think Sonny inherited this work ethic largely from his family, it also came from his peers – people like Andy Kirk, Jr, Walter Bishop, Jr. and Jackie McLean who all worked so hard to develop their artistic voices. And I think that Sonny heard Charlie Parker and knew how much time he had spent woodshedding just from hearing him. Knowing that only spurred him on to work even harder on his music.

JJM He also carried a feeling of inferiority with him throughout his life. Is that something that he was willing to talk about? Did he understand the genesis of this?

AL He felt growing up that he was the black sheep of his family, and he has spoken about that inferiority complex that he carried with him, especially being the youngest child in the family. That contributed to making him his own worst critic, and even after he far exceeded any expectations that anybody ever could have had for him, he remained his own worst critic.

So, where did he get that sense of inferiority? A lot of that likely came from his family, but I think it also came from growing up in a society that treated Black people as second-class citizens, which is something he probably internalized while growing up.

JJM Did this feeling of inferiority contribute to his drug use?

AL No. I think that drugs had become part of what some identified with the “jazz life,” and there were many drug users that Sonny and his peers looked up to. When they read that Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday used heroin, there was a sense that drugs might be a part of their creative genius. Of course that was not the case, but they did perceive it that way. To some extent, drugs served as a barrier or buffer to a society they felt disapproved of their music, but I don’t think that Sonny was using drugs out of a feeling of inferiority. Eventually, Sonny and his peers all realized that it was a myth that heroin made anybody play better, and some were able to overcome their addiction, while others didn’t make it to the other side. Sonny was an example of somebody who was able to conquer his addiction and not relapse, so for that reason he serves as a model of what has often been described as a “clean living musician” who never relied on drugs in order to play his music, and in fact he saw them as being detrimental.

JJM Rollins characterized himself as a “truly despicable person” when he was using drugs, and he had a bad reputation as an addict, becoming a pickpocket and even hawking other musicians’ horns. The drummer Max Roach advised others to “stay away from Bird and Sonny Rollins.” Did Sonny talk with you about those years?

AL Yes, and you’ll find that in the book. He has said that he’s not proud of those years, but I do think that his story of overcoming addiction shows his strength of character. Addiction is an illness more than it is a kind of pathology people have attributed to jazz musicians practically since the inception of the music, and when Sonny was coming up, he witnessed the cultural shift from criminalizing drug use exclusively to treating it as a disease or an illness.

Sonny participated in one of the first drug rehabilitation centers at the United States Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, a facility where some people were there voluntarily, and others involuntarily. There were many jazz musicians there – enough that it’s been said that the greatest band you’ve never heard was at Lexington. He continued developing his music there with musicians like Clifford Jordan who had come to Lexington to get clean. So, for a time, Sonny was certainly known in the musician’s community for his drug use, but his story of overcoming his addiction is what I’d rather focus on.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1953 recording of “Round About Midnight” from the Miles Davis album titled Collector’s Items (released in 1956). In addition to Miles Davis on trumpet, the recording includes Sonny Rollins (tenor saxophone); Charlie Parker (alto saxophone); Walter Bishop, Jr. (piano); Percy Heath (bass); and Philly Joe Jones (drums). [Universal Music Group]

.

JJM In the book you tell the story of Rollins telling Charlie Parker that he had quit drugs, which was a lie…

AL Yes, this was in 1953 at the Collectors’ Items session with Miles Davis. Prior to the session Sonny was using drugs with another band member, and when he got to the studio, Charlie Parker was so happy to see him and thought that Sonny had heard his message about quitting drug use, but this was not the case. At one point someone else who was there that day mentioned to Parker that he and Sonny got high before they came to the studio, and Sonny saw Bird’s face drop, and seeing the disappointment on his idol’s face sent him a clear message that he had to change his life. So, he eventually went to Lexington and had hopes that when he got out he’d be able to tell Charlie Parker that he got his message and was no longer using, but Bird died while Sonny was in Lexington and was never able to tell him. In the book I write a little about a memorial concert Sonny and other patients at Lexington performed in Bird’s honor at the drug rehab facility.

JJM Did he share any of his regrets about that time with you?

AL I would have to ask him specifically if he would think of this as a regret, but I think that he wishes that he had not gotten involved in drugs, which is why he dedicated himself later on to setting a positive counter example for the next generations – so much so that he didn’t want to work with anyone who was using drugs, and made a point of mentoring younger musicians that he worked with to stay clean.

JJM When did Sonny start to get noticed as a serious player by other jazz musicians?

photo courtesy of the author

Sonny Rollins at Birdland, with Art Blakey and Curly Russell

AL He began to be noticed around the jazz scene while going to jam sessions in the late 1940’s. So, word began to spread all over the city that Sonny was an up-and-coming player when he was a teenager – Miles Davis heard him playing at a session and offered him a gig, basically. The book also traces Sonny’s early involvement with people like Babs Gonzales, Bud Powell and Coleman Hawkins, who all took note of what Sonny was doing. He became something of a local legend as a prodigy in Harlem, however, in the press he wasn’t an overnight success. Critical acclaim came slowly for Sonny, and that’s something I felt was important to document in the book. It’s tempting to imagine that he became a “jazz legend” overnight, but that is far from the case. It was years before he was acknowledged as a titan of the tenor. Critics initially leveled some harsh criticism against Sonny.

JJM Yes, which is an interesting part of the book. Nat Hentoff at Down Beat was one of his early detractors, writing that “Rollins swings hard, and he plays with considerable warmth, but as has been stated here before, he lacks freshness of conception and his imagination is not individually distinctive enough to raise him to the top level of jazz improvisers.” As the years went by, of course, he became a darling of the critics, including Hentoff. Sonny felt more pressure because of that, didn’t he?

AL Yes. It’s lonely at the top, and Sonny’s self-criticism intensified as his reputation grew. I think he felt that he was not living up to the reputation of being the greatest tenor player of his generation, which he was effectively anointed as in the mid-1950’s by the critical establishment. That is something that contributed to his decision to step away from the scene and go and perform on the Williamsburg Bridge. He didn’t make this decision for the critics, he did it for himself because he felt he wasn’t living up to that standard.

JJM His two-year sabbatical – spent primarily on the Williamsburg Bridge from 1959 to 1961 – is such a well-known part of his biography. Were you able to uncover any more information about that time?

AL Yes. He documented quite a bit of what he was working on during that period in his practice notes, and there were also journal entries and love letters that he wrote to his wife Lucille that illuminate what he was working on musically and personally. These attest to the personal growth that he underwent – for example, he began exercising every day, even doing calisthenics on the bridge abutment where he practiced. He also got involved in the spiritual movement of Rosicrucianism during this time, which I document in the book as well. There was also a letter that he wrote in response to a college student who contacted him for a term paper in which he outlined his vision for the music to be a positive force in the world, to take it out to the clubs and especially the concert halls, where he hoped to change the public perception of what the art form represented. So, I think that I was able to illuminate that period of his life in a way that I found to be moving.

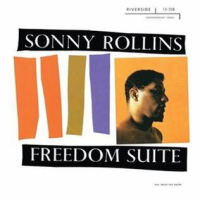

JJM Part of the marketing for your book includes Sonny’s role in the civil rights movement…

Rollins’ 1958 album Freedom Suite [Riverside]

AL Yes. Sonny’s civil rights activism goes all the way back to when he was about four years old, marching in the streets of Harlem with his grandmother, who hung a black nationalist flag. There is this perception that Frank Sinatra taught Sonny about civil rights when he performed at Sonny’s high school, Benjamin Franklin High School, but that couldn’t be farther from the truth. He was steeped in the civil rights struggle as soon as he could walk.

In the late 1950’s, Sonny decided that it was time to make a concept album, and the theme would be civil rights. Freedom Suite is an extended composition that he composed and then recorded with Max Roach and Oscar Pettiford, and it was really the first civil rights album of the civil rights era, and the album that I would hold up to exemplify his commitment to civil rights.

JJM It was interesting to read about Sonny’s style as a bandleader. He had challenges keeping musicians in his band – particularly drummers – who could live up to his perfectionist personality. What was it like for some of these musicians to play for him? What did they tell you about their experience with Sonny?

AL Sonny had exacting standards, and he was particularly hard on drummers, who had to be in excellent physical shape in order to keep up with Sonny Rollins. One pattern that I noticed in interviews was that Sonny’s drummers would sweat so much that they needed to have a change of clothes ready to make it through a concert. If they forgot, they’d be soaking wet at the end.

So, yes, he would not have any compunction about letting someone go if he felt they were not meeting his standard, but oftentimes he would get the best out of people. And he worked with a “who’s who” of jazz drummers, many of whom got their first break playing with him – Pete La Roca, for example, was recommended to Sonny by Max Roach, and he went on to having an illustrious career. It was like a graduate school for some of these drummers to play with Sonny. People like Ben Riley, who came to Sonny after he was on the bridge, or Roy McCurdy, who got his first endorsement as a result of his association with Sonny. The list goes on and on. Playing for Sonny would always be trial by fire, but what I found is that musicians took themselves to the next level through his example.

.

A video interlude…Watch Sonny Rollins play the tenor sax, unaccompanied, during a 1979 Tonight Show appearance

.

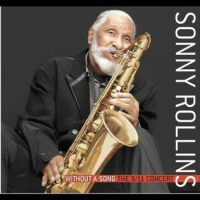

JJM The opinion of many is that Sonny’s live performances are legendary, but his studio recordings don’t often communicate that excitement. An interesting part of your book concerns the secret recordings taken by a fan by the name of Carl Smith, who was able to capture Sonny live. Sonny wasn’t originally happy to learn about these recordings. How did they come about?

AL Carl Smith lives in Portland, Maine, and he co-founded a high-end audio company called Transparent Audio. Around the year 2000 he became aware of what Sonny could do in a live setting. He was so blown away by what he’d seen and heard that he made it his personal mission to let the world know that Sonny was doing something very special, and that people ought to take note of it.

Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert [Milestone]

Smith noticed there was often a disparity between what was heard on record and what was heard on the bandstand, so he began devising a method to record Sonny at live performances and produce a recording himself. He had state-of-the-art equipment in order to make sure that he would capture the highest possible quality audio, and he brought friends to sit on either side of him and instructed them not to applaud so as not to interfere with the audio recording. He also sat in front of the speakers so the sound he captured was coming straight out of the bell of the horn. When Sonny and his wife and manager Lucille found out about this, they were irate, especially Lucille, but this recording – made in Boston on September 15, 2001 – was eventually released in 2005 as Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert, which won Sonny a Grammy Award.

Smith generously offered to share his entire collection with me for the duration of this book, and it is a major archive for telling Sonny’s story, because as you said, you can’t tell the story of Sonny Rollins based purely on his studio albums. That misses a big part of the picture. So, Carl Smith’s collection is important, and I’m glad that he undertook the project because it offers a clear insight into Sonny’s greatness as a performer. It also became a central piece of the Road Shows compilation albums, which were culled from live performances through the decades, four volumes of which Sonny has released on his own record label, Doxy.

JJM And they are fantastic recordings. As you said, Sonny and Lucille were not happy about Smith creating these recordings without their consent, and as a result had questions about his integrity, but the critics Gary Giddins and Stanley Crouch helped make Sonny and Lucille understand that Smith didn’t have any intention of profiting from these recordings and eventually Sonny was convinced to release these recordings on Doxy.

Rollins’ 1956 recording with Clifford Brown, Max Roach, George Morrow, and Richie Powell

.

The Standard Sonny Rollins, 1964 (with Herbie Hancock, Jim Hall, Bob Cranshaw, Mickey Roker, others)

AL Yes, Crouch and Giddins were major supporters of Smith’s work, and when Sonny met with Smith he saw that Smith had no ulterior motive other than to advance the music, which convinced Sonny to collaborate with him, and to even listen to some of the material he had in his collection, which was always painful for Sonny. But fortunately he managed to do that, and we’re all the better for it.

JJM What are some of Sonny’s favorite recordings of his own work?

AL It’s tough to give a definitive answer, but in the book I discuss several he seems to particularly like – two that stand out are Sonny Rollins Plus Four and The Standard Sonny Rollins. But I think that I’ll paraphrase Charlie Parker, who did an interview with Down Beat that was part of a regular feature called “My Best on Wax,” where the question was asked of the musician, “What is your best on wax?” Bird’s answer was that he hadn’t made it yet, and I think that Sonny always thought that way.

JJM How do you feel Sonny wants to be remembered? Did he talk with you about that?

AL I think Sonny wants to be remembered as somebody who always worked to better himself, and as somebody who followed the Golden Rule, to “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” He is even starting a nonprofit organization to promote the importance of living by the Golden Rule. He and I have spoken a lot about the Golden Rule and how difficult it is to live by that, and how many people don’t do it. But I think that Sonny wants to be remembered as someone who worked hard to live by it.

.

.

photo courtesy of the author

Sonny Rollins on the Williamsburg Bridge, October 7, 1961

.

“Life is not forever. We have a short period to learn and do something correct…Life is not about cake and ice cream and enjoyment. Life is short, and it’s important to do something.”

-Sonny Rollins

.

.

Listen to the 1962 recording of Sonny Rollins playing “The Bridge,” with Jim Hall (guitar); Bob Cranshaw (bass); and Ben Riley (drums). [RCA Records]

.

.

___

.

.

Saxophone Colossus, the Life and Music of Sonny Rollins [Hatchette Books]

by Aidan Levy

.

Aidan Levy is the author of Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins and Dirty Blvd.: The Life and Music of Lou Reed, and editor of Patti Smith on Patti Smith: Interviews and Encounters. A former Leon Levy Center for Biography Fellow, his writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Village Voice, JazzTimes, The Nation, and elsewhere. He is a doctoral candidate at Columbia University in the Department of English and Comparative Literature, where he has served as co-convener of the African American Studies Colloquium and works with the Center for Jazz Studies. For ten years, he was the baritone saxophonist in the Stan Rubin Orchestra. He lives with his family in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

.

.

___

.

.

Praise for Saxophone Colossus

.

“Levy paints a vivid picture…Throughout SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS he weds his extensive research to a feel for detail and narrative; the book is certainly long, but it has too much great reporting to be dry.”

—Los Angeles Times

.

“An incredibly deep, well-researched and thoughtfully written biography.”

—DownBeat

.

“A memorable work that will become the standard biography of the saxophone giant and should be embraced by all jazz fans and general readers. Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

.

“Sonny Rollins told stories through his horn. His ‘telling,’ no matter how intricate or elaborate, was always pure, honest, and vulnerable, while the storyteller himself remained elusive and intangible. Until now. In Aidan Levy, Mr. Rollins has found his chronicler, an immensely talented writer whose lyricism, mastery, and dedication to truth matches that of his subject. The result is an opera, a calypso, a magnificent symphony that captures All of Him: Sonny, Newk, Theodore, Wally, Brung Biji, and the one and only Saxophone Colossus.”

—Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

.

“When I was a boy, I knew nothing of Sonny Rollins, the man, but his music set me free. Now, forty-some-odd years later, this book has gifted me a profound, almost revelatory, appreciation of all it took for our singularly Great American Improviser to exist, to persist, to survive, to thrive, to comprehend, to transcend, to create, to liberate, to be — at once the towering, omnipotent, immortal Colossus and the humble, gentle, questioning, questing human. Sonny Rollins has always been the master storyteller of the jazz idiom. What an illuminative joy it is to finally read the story of his own life so exhaustively and engagingly told.”

—Joshua Redman, Grammy-nominated saxophonist, composer, and educator

.

“Sonny Rollins is the most acclaimed and celebrated jazz musician alive. His fearless creativity and willingness to test his limits are the stuff of leg- ends, as are his modesty, discipline and self-criticism. With deep research and meticulous documentation, Levy, with the aid of Rollins, gives us a revelatory and richer picture of the man and his era. A colossus of a book.”

—John Szwed, author of Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra and So What: The Life of Miles Davis

.

“The life and music of Sonny Rollins as chronicled by acclaimed author Aidan Levy is an insightful view into the daily struggles, achievements and spiritual journey of whom I like to refer to as the ‘Maestro di Maestri,’ Mr. Sonny Rollins. All I can say is: READ. LISTEN. LISTEN. READ. You will be enlightened as I am.”

—Joe Lovano, saxophonist, composer, producer, educator and Grammy winner

.

“Aidan Levy has provided the jazz world and beyond an important documentation of one of the greatest musicians of all time. Sonny Rollins spoke his own language through the saxophone–just check out his solo on ‘Alfie’! And Saxophone Colossus provides for us in words a portal to deeper understanding of this legendary jazz giant!”

—Terri Lyne Carrington, Grammy-winning drummer, producer, and composer

.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on November 14, 2022, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to click here to read our interview with Gary Giddins, in which the most-eminent jazz critic of his generation discusses Sonny Rollins.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support Jerry Jazz Musician

.

.

.

I read in another review of this book about an event described in the that I witnessed at McKie’s in Chicago in the spring of 1964. It was my senior year of EE at U of Cincy, and I had driven all night for an interview at a major electronics company. They put me up in a hotel, and after the interview, I slept all day, then drove across town to hear Newk.

McKie’s was a “shotgun” storefront — a narrow club running from the street to the back door, with a bar running nearly all of its length, a narrow aisle, and I think seating on the other side of the aisle (it was 50 years ago, and the club closed not long afterward). Newk began the set playing phrases as he emerged from the dressing room (office?), striding through the club to near the front door, where he crossed behind the bar to the stage, where he moved back and forth as he played, and eventually ended the set retracing his steps still playing, uninterrupted, as he disappeared into the dressing room. It was the most music I’d ever heard in my life (and I’d heard Trane earlier that winter, Basie, Kenton, and Mulligan’s CJB in Cincy), and I resolved that I would take any job offer that resulted.

I heard Newk live once after that, probably in the ’80s or ’90s, in a large student lounge of U of Ill. It was also memorable.