JJM You wrote that Parker “worked for everything he got, and whenever possible, he did that work in association with a master.”

SC Well, he sought these masters out because one of the things that all of them had in common was an ability to create on the moment a sound that reflected their personalities. Roy Eldridge’s approach to the trumpet couldn’t be argued with because he could play so much trumpet and he was so unpredictable as a player. Chu Berry was the same kind of player, and clearly Lester Young was the same kind of player, and Buster Smith was the same kind of player. They didn’t play the same styles even vaguely, but they all had this uniqueness about themselves that they had discovered through practicing at home and improvising in public. They all had what today is called a very strong work ethic — they worked very hard on their instruments and on knowing harmony and on knowing all kinds of different ways to get through different problems on the bandstand until they could consistently do it on a startlingly good level. That was what they wished for and that was what they fought for and that was what they ended up having.

JJM Parker’s drug use is such an important part of his biography. When did he begin to notice, as you write, that his appetites “were larger than those of others, that he started to sense that he was somehow a danger to himself.”?

SC Well, he told Doris Parker that he got so far into the nightlife that he would at times stay up and take Benzedrine so he could play and continue to practice, and then take some more so he could continue to play and practice. He was so immersed in the idea of practicing and learning more music that he would disappear, to the point where his mother would have to go out and find him. She would get him home, which he was grateful for because, as he told Doris, if it hadn’t been for her he might have just never come home at all. So it was at that point that he began to become aware of the fact that he was endangered by his appetite.

He would be gone for three or four days, his mother would go find where he was, she would bring him home, he would take a bath, eat, and then he would sleep for two or three days in a row, and then he would get up and go back out for two or three or four days. So that was the life he was living at around age 17 and 18.

JJM So, was he living clean when he left for Chicago, and then to New York?

SC Well, I learned that he was through Bob Redcross and Biddy Fleet. When Bob encountered him in Chicago he wasn’t using drugs, and Biddy Fleet got with Parker when he came to New York, and he said he wasn’t getting high then either. So it’s fairly obvious to me that he had kicked the habit before he hopped a train to Chicago, and again after he hopped a train to New York. What he learned from Buster Smith, I am sure, is what kept him from making the kind of mistakes that an impressionable young guy could have made, which was to put himself in absolute danger as a drug addict on the road, hopping trains with no connections to any new drugs, and also running the danger of encountering what they call the railroad dicks, who were the police who worked there with clubs and who would beat up the bums. So, Charlie Parker avoided all of that by simply controlling his habit.

Doris Parker told me that people always thought of Charlie Parker as being weak, but she said he wasn’t weak because he was able to kick the habit by himself many times. The environment kind of overwhelmed him because there was so much dope around and so many people thought they were doing him a favor by giving him free drugs after he became very famous, which they didn’t do when he wasn’t famous. So, he was very aware of the fact that he couldn’t be out there strung out and he got that problem behind him — and it was apparently behind him for about a year-and-a-half until he had to come back to Kansas City, and then he got in trouble again.

JJM When Parker did arrive in New York, he was surprised to discover that Buster Smith hadn’t made his mark on the town. You wrote, “New York was full of so many good musicians, and there was so much going on, that it was easy to get passed over.” Did Smith’s relative lack of success alter Parker’s plans for his time in NY?

SC Well, it altered his plans, yes, because he thought he was going to get into Smith’s band since Smith told him before he left Kansas City that he would start a band and put Charlie on the bandstand with him. So Charlie Parker arrived in New York assuming that was going to happen, but Buster Smith wasn’t gigging. He still had a lot of respect among Count Basie and the Kansas City musicians in New York, but Basie had a had full band that was working very well together and making records, so the possibilities for Buster Smith were limited primarily to arranging and composing some tunes for the band. So Charlie Parker was there with his mentor, but his mentor wasn’t gigging, which meant he wasn’t either. But, he was in New York and determined to be accepted in New York — just as determined as he was to be accepted in Kansas City.

JJM But he wasn’t really accepted by the musicians of New York, and there was a lot of criticism about his playing. Did this lead to some self-doubt?

SC Yes, it left him with some self-doubt. Biddy Fleet points out that when Charlie Parker first started playing in New York, people didn’t like the way he played, and that basically they didn’t like him because he had a different kind of tone, and his phrasing was different. Many of the journeymen New York musicians told him he should play the saxophone more like it was being played in New York City and not try to come in with this strange kind of Kansas City approach that hadn’t yet made a place for itself in New York. They basically thought it was worthless.

But Biddy Fleet was very important to Charlie Parker because they both worked on these new harmonies. They both listened to European concert music. They both understood that there was something else that was possible in music than what guys were playing at that time, and so Biddy Fleet would tell him to ignore these people and just keep playing. He told Charlie that if he wanted to satisfy the public, he would never play the horn. So Biddy Fleet understood at the end of the 1930’s that there was a line between serious playing and entertainment, which was a thin line and could sometimes be straddled by players like Duke Ellington. There was a way you could play artistically and satisfy the public, but that was something that one had to figure out how to do, and the Kansas City musicians, as personified by Count Basie and his band, had figured that out. That was what Charlie Parker was challenged to do.

JJM Your book concludes with his need to return to Kansas City because his father was murdered, and I am assuming your next volume will pick up from there. In addition to the resources you used for this first volume, who are some of the resources we will see in the second volume?

SC Yes, you will see some of the same people, but I also got a lot of information from other people who were around him at that time — people like Max Roach and his second wife Doris Parker, who gave me a fuller picture of Charlie Parker as he became who he was. They had some very telling things to say about him, things that are beyond what we normally hear about Charlie Parker.

JJM Well, fans of Parker will be excited to read that…

SC Thanks.

JJM How has Charlie Parker’s influence on jazz music changed, if at all, since the time you began writing this book in the 1980’s to the present day?

SC Well, the only thing that has changed about his impact is that more people today may feel that they can avoid it with an academic approach that doesn’t have the kind of vitality that Charlie Parker’s real playing had. So you hear guys playing a lot of patterns and a lot of scales and a lot of simplistic or pretentiously complex foundations, and they don’t necessarily get to what Charlie Parker got to, which was a way to keep the absolute vitality of the blues and swing at the center of his aesthetic. So his style always carries the blues and always swings in a way that today many musicians think they can avoid because they are academically trained. That’s an unfortunate thought, but I don’t think it’s going to work for long. Anybody who thinks that will work should hear Charles McPherson when they get a chance to hear him, and on the other side they should listen to Wynton Marsalis on YouTube playing his Abyssinian Mass. There is some trumpet playing on there — the way he pivots from swing and from the blues — that should let people know that it is still the undeniable demand for vitality in jazz.

JJM Are you still actively involved in the Jazz at Lincoln Center program?

SC Now and then, but not all the time, because I have been busy doing other things.

JJM Given how busy you are, are you able to spend as much time writing about jazz as you would like?

SC For now, yes. In my book Considering Genius I was actually able to lay out what I was seeing over a period of 30 years — a period of talking to the musicians, seeing them in in nightclubs and concerts and festivals, and assessing what they did. So that is part of it. The Charlie Parker story is another part of it because it allows me to stand up to the greatest challenge for any biographer, which David S. Reynolds and I were just talking about. He wrote the great book Walt Whitman’s America, and he also wrote about Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown. While we were talking we agreed that the fundamental challenge to a biographer is to make the data come alive, and to make it possible for you or any other reader to believe what the truth actually is — not just part of the truth, and not to exaggerate it. So making the data come alive for the reader was what I was trying to do in Kansas City Lightning, and that’s what I’ll be trying to do in the next volume of the Charlie Parker story.

JJM Was there a jazz biography you read as a young man that was a favorite of yours at the time?

SC I don’t recall any, although I liked Ross Russell’s book on Parker when I read it, but the more I developed and the more I came to know, the more difficulty I had taking it completely seriously. While there’s a lot of stuff in there that’s true, there are too many urban legends in there that I’ll clarify in the next book.

_____________________

“You could look at Bird’s life and see just how much his music was connected to the way he lived…You just stood there with your mouth open and listened to him discuss books with somebody or philosophy or religion or science, things like that. Thorough. A little while later, you might see him over in a corner somewhere drinking wine out of a paper sack with some juicehead. Now that’s what you hear when you listen to him play: he can reach the most intellectual and difficult levels of music, then he can turn around — now watch this — and play the most lowdown, funky blues you ever want to hear. That’s a long road for somebody else, from that high intelligence all the way over to those blues, but for Charlie Parker, it wasn’t half a block; it was right next door.”

– Earl Coleman

_____

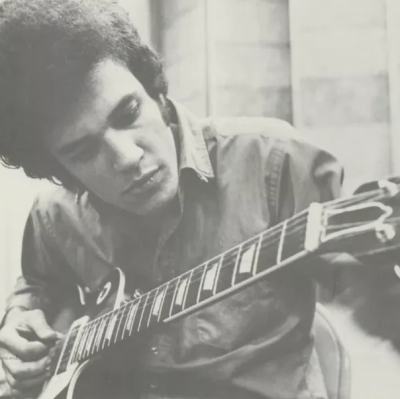

A 1950 film of Charlie Parker and Coleman Hawkins

Critical Acclaim for Kansas City Lightning

“A tour de force that is the print equivalent of a long, bravura jazz performance. . . Crouch has given us a bone-deep understanding of Parker’s music and the world that produced it. In his pages, Bird still lives.”

— Washington Post

“It is from Mr. Crouch, a novelist as well as a critic and essayist, that we come to see Charlie Parker in the context of his time and place in America. . . One comes away from Mr. Crouch’s book wanting more.”

— Wall Street Journal

“Kansas City Lightning succeeds as few biographies of jazz musicians have. . . This book is a magnificent achievement; I could hardly put it down.”

— Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

“This is a memorable book. . . Stanley Crouch takes us deep into places most of us can only imagine—including into the heart of the mysterious split-second alchemy that takes place nightly on the bandstand.”

— Geoffrey C. Ward

“A book about a jazz hero written in a heroic style. . . a bebop Beowulf.”

— New York Times

“[Crouch] crafts lush scenes and crackling music writing. . . Jazz fans will want to read this book. . . This is a thorough and entertaining account of one of the greatest rises—and the prelude to one of the greatest falls—in jazz history.”

— NPR.org

“[A] riveting, long-awaited book . . . Here is Bird making his watershed discoveries before he fired his own lightning bolts.”

— Gary Giddins

“A portrait of the young Charlie Parker with a degree of vivid detail never before approached. . . [Kansas City Lightning is] a deft, virtuosic panorama of early jazz. . . This is a mind-opening, and mind-filling, book.”

— Tom Piazza

_____

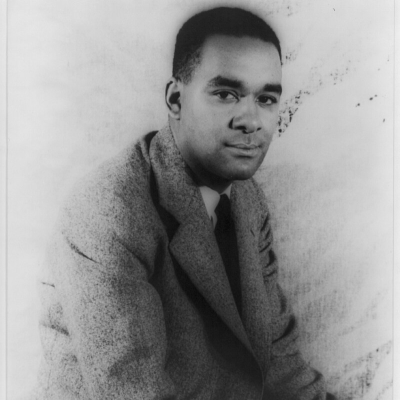

About Stanley Crouch

Stanley Crouch has been writing about jazz music and the American experience for more than forty years. He has twice been nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, for his essay collections Notes of a Hanging Judge and The All-American Skin Game. His other books include Always in Pursuit, The Artificial White Man, and the acclaimed novel Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome. Since 1987 he has served on and off as the artistic consultant for jazz programming at Lincoln Center and is a founder of the jazz department known as Jazz at Lincoln Center. The president of the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, he is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a regular columnist for the New York Daily News.

____

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews with Stanley Crouch

Stanley Crouch, author of Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz

The Ralph Ellison Project: Stanley Crouch discusses Invisible Man author Ralph Ellison

*

You may also enjoy reading our interview with Brian Priestley, author of Chasin’ the Bird: The Life and Legacy of Charlie Parker

Great interview, Joe. Stanley does have Parker down in this book, though some of it wanders, I think. But he knows Bird’s essence: “keep the absolute vitality of the blues and swing at the center of his aesthetic.”