.

.

In this February, 2004 interview, Donzaleigh Abernathy — the daughter of Reverend Ralph Abernathy — talks about her life as a child of the civil rights movement, and remembers the two visionaries who changed the course of American history

.

.

___

.

.

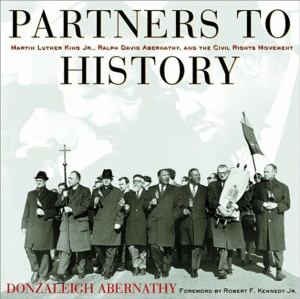

Donzaleigh Abernathy,

author of

Partners to History:

Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and the Civil Rights Movement

.

.

___

.

.

…..Ralph David Abernathy and Martin Luther King Jr. were inseparable and together helped to establish what would become the modern American Civil Rights Movement. They preached, marched, and were frequently jailed together.

…..Donzaleigh Abernathy, Ralph’s youngest daughter, has written Partners to History as a testament to the courage, strength, and endurance of these men who stirred a nation with their moral fortitude. She also pays tribute to the thousands of unsung heroes — the other partners to this history — who were foot soldiers in the endless struggle for freedom, justice, and equality. She writes, “Far too many sacrifices were made for our freedom to let history repeat itself. It is for these peaceful warriors, the soldiers of freedom, that I pause to remember the road that brought us all across.”

…..Donzaleigh Abernathy, Ralph’s youngest daughter, has written Partners to History as a testament to the courage, strength, and endurance of these men who stirred a nation with their moral fortitude. She also pays tribute to the thousands of unsung heroes — the other partners to this history — who were foot soldiers in the endless struggle for freedom, justice, and equality. She writes, “Far too many sacrifices were made for our freedom to let history repeat itself. It is for these peaceful warriors, the soldiers of freedom, that I pause to remember the road that brought us all across.”

…..Ms. Abernathy joins Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a February, 2004 interview about her life as a child of the movement, and to remember the two visionaries who changed the course of American history, and inspired the world.#

.

.

___

.

.

Warren K. Leffler, via Wikimedia Commons

“Our method is one of passive resistance, of nonviolence, not economic reprisals. Let us keep love in our hearts but fight until the walls of segregation crumble.”

– Ralph David Abernathy

.

.

___

.

.

JJM Before we get started on the interview, I have to tell you that I was quite surprised by how emotional I got while reading your book. I am fifty years old, and it took me back to all kinds of long unvisited memories and images. What you wrote regarding your own experiences with your father, and of being a child of that generation smack dab in the middle of the events of the civil rights movement was deeply moving.

DA Thank you. I appreciate your sharing that with me. I put my heart into the pages, and when the work is done you hope it comes back to you in a positive way. The overwhelming message of the book is about love, and of us coming together to make a better society. It’s impossible to know how people are going to respond, and I never thought I would create a book that would make grown men cry. And I owe an eternal debt of gratitude to my friend Dar Dixon Bijarchi for supporting me through the writing of this book, and for teaching me about love and acceptance of different cultures.

JJM You wrote in the introduction, “I have written this book to document in photographs the history of the struggle for civil rights in America. It is said that ‘a people who do not know their past are destined to repeat it.'” Your book is filled with remarkable photos, many of which I have never seen before, and many of them are your own family’s photos. Have these been published before?

DA My family’s photos have not been published before, and many of the other photos from the wire services and Corbis-Bettman haven’t been published either. I was told that when someone would put out a book on the civil rights movement, the Associated Press was contacted, who would then pick out the first photo on the pile, and that is what appeared in the publication. But for this book, I felt it was important to dig deep, because I wanted to tell this story visually. In order to do this, I needed to gather everything I could from the AP, Corbis-Bettman, the Library of Congress, Black Star, Magnum, and others. I kept going from photo lab to photo lab, gathering photographs. Once I got photocopies of the pictures I laid them all out, and in the process discovered all the different angles of the same story being told. The question then became finding the right photographs to tell the story, and the best way to do so was by using a series of them. I ended up with a really big, thick book that the first editor was not happy with. He thought it was too graphic, in a way that made him ashamed of the atrocities that occurred. He wanted to tone down the violence, and even though that was a key part of the story, I had to respect his wishes and understand that it may be too much for readers to take. We would go back and forth about the photos to use, and instead of having four photos tell a story, I had to cut it down to two or three — and sometimes even one — carefully picking and choosing. There were so many that didn’t make the cut which were absolutely incredible, photos that I wanted so much to be a part of this book. In addition to the photos, I had two hundred pages of text. So, I needed to make choices and create a book that people could digest, learn from, as well as afford. It was of great importance to me to make this history accessible, and to touch reader’s hearts, tell them the truth, and invigorate them in order to inspire even better change for America.

JJM I loved how you described your relationship with your dad. I knew him in a way most everyone else from my generation likely knew him — from the evening news or in the newspaper. From those reports, it was clear to me that he was a very warm man. Who served as his mentor when he was a young man?

DA Dr. Vernon Johns, who was the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church before Martin Luther King came to town. My father met Dr. Johns when he was a student at Alabama State. Dr. Johns had this pioneering political thought that black people had to stand up for their rights in Montgomery. He felt that segregation was a horrible thing, and that it was very important to stand up to it. During that period of time, a black man couldn’t even look a white woman in the eye or tell her she had done something wrong. His only recourse was to cast his eyes down and say “Yes Sir,” or “Yes Ma’am,” and take a position of humility. No matter how old you became as a man, you were still considered to be a “boy.” As a woman, no matter your age, you were a “gal.” Dr. Johns would say, “Stand up to this!” When Uncle Martin came to my parent’s house for the first time with Dr. Johns, he had a chance to hear Dr. Johns talk to Daddy the way he always did, about what needed to be done in the community regarding civil rights.

At the time, Daddy was working as a field director with the NAACP, where Rosa Parks was secretary, and when Rosa was arrested, it was only right that they organize and do something to protest the arrest. Out of this they created an organization to rally around called the Montgomery Improvement Association. Because Uncle Martin was the only pastor in Montgomery with a Ph.D., it was felt that the white world would respect him. Couple that with his amazing preaching voice, and the fact he and my Daddy were best friends, it was natural that they would begin working together.

Their partnership changed the course of history as we know it. Because of their efforts and of many others, after enduring two hundred forty-three years of slavery, a period of reconstruction and one hundred years of Jim Crow — the equivalent of apartheid — black people were truly free in America for the first time. We got the right to vote, we could use public accommodations, we could try on clothes in department stores — all things that people take for granted now that we couldn’t do before. I will never forget, as a little girl, not being able to have dinner in the Marriott Hotel in Atlanta. I was in elementary school by the time we finally got to eat there. It was a big thing!

JJM At one point in the book you wrote about how your mother was saddened by your family’s decision to move from Montgomery to Atlanta in 1961. Clearly your father had great individual challenges during the civil rights movement that many of us are aware of, but what was your family’s greatest challenge?

DA Before I was born, our family home was bombed while my mother and sister were in the house. During my own childhood, several times a week some hateful, racist person would call during dinner time and tell my mother what would become of us and my father. She would hang up the phone and we would eat the remainder of our dinner in silence. So, the biggest challenge was probably in trying to find happiness and humor and the ability to keep going in the midst of all this stress.

My mother was incredibly strong. If it were me in her position at that time, I probably would have told my husband that you can’t do this anymore, that I can’t have our family live in fear like this. She had an amazing ability to summon up her courage. Since my Daddy was often times gone Monday through Friday, she raised us almost as a single woman. She would tell us not to worry, that everything would be okay. She would get us involved by telling us to do our part in integrating the local elementary school, and to participate in the civil rights marches. And every time something happened that would create fear in us, it did not stop her — in fact, it strengthened her. She was convinced that what my father was leading and what we as a family were doing was the right thing, and each child was expected to do their part.

JJM So your parents had high expectations for you to participate, even as a little girl.

DA Oh yes.

JJM How did your father’s philosophy of non-violence affect your daily life?

DA Well, when you are a little kid, you don’t necessarily want to be non-violent. Kids want to beat up on their siblings and carry on, but we couldn’t. We couldn’t even play with water guns or any of the other toys children played with at the time. We could fill up a balloon with water and squirt each other with it, but that was about it. I will never forget how the little white girls at school would come to fight me, because I was the only black girl in the class, but I would tell them I would not fight because I am non-violent. They were amazed by that, and I repeated that I am non-violent and am not going to lower myself to fight them, that I am above that. I wanted to sound philosophical when communicating to them, which was something my father taught me, and I was supposed to quell the violent urges of other people, as well as my own, and make non-violence a way of life. Even in the privacy of our home, when we would complain about people who didn’t treat us right, my father was the first to say that it was inappropriate to talk unkindly of others, that it was important to understand their perspective. It was a huge moral code we were expected to live by within our family.

JJM When you were a little girl did you have a sense of the enormity of the events that your father and Uncle Martin were leading?

DA Yes, but only because I went to the March on Washington. I was four years old at the time, and I had never seen such a sea of people. While I knew the event was something big, I didn’t realize the importance of it. I knew his work was important because I would see him on the news, and other little children’s parents were not. I would see him and Uncle Martin on television, speaking throughout the community all the time, and it became a normal thing. So, yes, I understood the size of it, but the not the importance — probably not until I became a woman. And, I have to say that I didn’t know that Uncle Martin was anything other than Uncle Martin, and Daddy was anything other than Daddy. When Uncle Martin died, Daddy worked so hard to establish a national holiday in his honor, and all of a sudden Uncle Martin rose as this legend. I remember wishing I had known how enormous their work was, and I should have paid more attention! But, I was just a little girl at the time, rambling through stuff in their office. I used to play in Uncle Martin’s office and go through his papers and books, messing everything up. And at the end of church, all of us would go over there and drink his ginger ale.

JJM Did he scold you about that?

DA Never. Uncle Martin would never scold us, and Daddy wouldn’t either. They were such wonderful people. What was remarkable about them is that even with all the enormous events they were responsible for, first and foremost they were about family. My Daddy was often gone between Monday and Friday, but on Saturday morning he would make breakfast for everybody. And in the afternoon, he would take my brother to the barbershop, or he would go to a football game or come see us at ballet. Uncle Martin would do the exact same thing with his family. Every Sunday for as long as I can remember, our two families would get together for dinner, and we would take our summer vacations together as well. On Wednesdays, when Daddy and Uncle Martin were in town, we would go swimming at the YMCA. It was all about family.

JJM Did your father talk much about his own fears?

DA He didn’t talk much about fear, but he used to tell us that he might go away some day and not come back. He wanted us to understand that death was not a bad thing. I remember that he talked quite often about courage. He felt that courage is what allowed us to rise up against fear and move forward.

JJM What would you say was your father’s defining career moment?

DA I would have to say getting all that legislation passed — the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Public Accommodations Act — and leading the Poor People’s Campaign in Uncle Martin’s absence. After Uncle Martin died, Daddy was there to see that the Affirmative Action legislation was passed, and that the CETA program was put into effect. He fought for the food stamp program as well. And, if you are a poor child today, you can get a hot lunch at school thanks to my father’s efforts. My father also took part in the defense of Russell Means and Dennis Banks during Wounded Knee, and helped negotiate a peace settlement between the FBI and the American Indian Movement before any blood was spilled.

JJM Yes, I remember that.

DA Yes, Daddy did great things — many of which are still in existence. Abernathy Towers, for instance, is a home for senior citizens and the handicapped. And, of course, we celebrate the Martin Luther King holiday because of his work and that of many in Congress. His lobbying efforts were instrumental in the creation of this holiday. So, every time we celebrate that holiday, our family also celebrates Daddy’s work, and for making his dream of a day honoring Uncle Martin a reality. It is likely that this holiday is what many people will say was Ralph Abernathy’s greatest contribution.

JJM How did the news of your Uncle Martin’s death reach you?

DA My mother received a phone call from a friend, who told us to turn on the television. She yelled at us from across the room to turn the news on, and there it was, information that Uncle Martin had been shot — not that he was dead, just that he had been shot. My sister started crying immediately, and I told her it was going to be okay, and reminded her that Uncle Martin was stabbed before and lived, and since he has such important things to do, God would never let him die. Andrew Young called right about then and told us to get on an Eastern Airlines flight at the Atlanta airport, and that Aunt Coretta (King) would be there as well. That was all we knew at that point.

Dr. Otis Smith, a dear friend of ours, came to the house and picked up my mother, my brother, and me, and took us to the airport. I remember it being a very long ride. My heart was hurting, and I was very fearful, because everyone was crying. I prayed to myself, reminding myself of my faith in the Lord.

When we got to the airport, the press was everywhere. We were standing around on the tarmac, and my mother and Aunt Coretta were together, slightly away from me. Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen walked over to Aunt Coretta and said something to her, and then she and my mother embraced. They hugged each other and began to cry, and that is when I started crying, because I knew at that moment Uncle Martin was gone. I stood there on the tarmac with my brother, who was sobbing, and some reporter stuck a camera in my face and started filming. I was mortified, because I had just lost my Uncle Martin. My mother got on the plane and went to Memphis to be with Daddy. Aunt Coretta went back home to be with her children, and left the following morning for Memphis.

The next afternoon we all went to the airport and waited out on the tarmac. After the plane arrived, everyone walked off the front part of the plane. Then, I saw the wooden box that Uncle Martin came home in slide down the back of the plane, and it absolutely devastated me. From there we went to Hanley’s Funeral Home. We went with the body, because Daddy wasn’t going to leave him alone. Daddy never left him alone during that entire time. He was with him when he was shot, and Uncle Martin died in my father’s arms. He accompanied him to the hospital, to the morgue, and to witness the autopsy. He was with him everywhere he could possibly be until they put him in the crypt in the cemetery.

JJM You marched during the funeral procession as well…

DA Yes, we had a funeral march, and we also had a march in Memphis. The sanitation workers of Memphis were not allowed to march prior to Uncle Martin’s death, but the city gave them a permit to do so after, and we went there to join it. The funeral march was incredible. There were more people there than I can even recall. I remember being jammed, pushed and separated from my mother. It was insane.

We had arrived at the King house earlier that morning, and the limousine left from there. Daddy wasn’t there, because he had gone to the funeral home to be with Uncle Martin. We met him at the church, and there wasn’t any way to really connect with him. It was as if there was a veil over him and nothing could penetrate his sadness and depression.

JJM Do you remember how your father spent his days immediately following the death of your Uncle Martin?

DA In quiet. He went about his necessary business, and he assumed the leadership role, which Uncle Martin gave him before he died. He told my father that if anything ever happened to him, he had to take our people forward. So, while Daddy was determined to see this work through, he was deeply depressed. He would come home and sit in his chair in the darkness. He grieved an awful lot, and did so for years. When I got a little older, I wrote him something that spoke about his grief and my anger toward Uncle Martin, because when he died, he took my Daddy with him.

JJM Did you ever express any anger to your dad about the person found guilty of Dr. King’s murder, James Earl Ray?

DA No, because we immediately felt that he didn’t do it. We felt it was J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. We knew they were watching us. When I was a little child, we actually found a wiretap device in our living room. One day a bird flew through an open window of our house and into the living room. We were able to get the bird out, but not before it found a bug — a wiretap device. We had these sconces on the wall, and while I was playing I could hear voices coming from them. Because the bug malfunctioned we could now hear the FBI talking to one another! My mother called Daddy and Uncle Martin and it was just so funny. So that is when I knew they were watching us.

JJM And what year was this?

DA This would have been about 1966.

JJM Two years prior to your uncle’s death.

DA Yes. We felt it was very important that James Earl Ray have a trial so everything could come out, because we believed that there was a conspiracy, and to this day I believe that there was a conspiracy. Ray was just a patsy, as far as I was concerned. While Hoover may not have been the trigger man, he was determined to stop Martin Luther King.

I know they wanted to come after my father as well, which always amazed me, because he lived his life almost like a saint. He was such a good Christian man, obsessed with the church and prayer and God. When Uncle Martin died, all he had was prayer, because it made him feel safe. So that is what he did. He devoted himself to the church, the Movement and serving humanity. Daddy truly believed that the more good you give to people and the better you strive to be as a human being, the more you will be rewarded by God, and all His blessings will come to you. He used to quote the scripture to us, about doing God’s work and what is right. That is one of the reasons I had to do this book, because it is the right thing to do. I don’t know another way to describe my Daddy other than to say that he was holy. He was striving every day to do what is right.

JJM Near the end of his life, your father called you on the phone and said, “I just called to say, my dear, I’m sorry for not being there for you all the years of your childhood. You were not the most important thing in my life then. It was the Movement. You were second and I’m so sorry.” What a heart wrenching admission that must have been for him. How did you respond to this?

DA I started crying. I knew that I wasn’t the most important thing at the time. He loved going on the road, serving humanity. I used to help him pack his bags, and he would get an extra pep in his step before leaving. It hurt me that he was so sad about not being there for me, when in fact he hadn’t denied me anything. While I do wish I could have had his undivided attention more, he did something so much more important — to make the world a better place for me to live. He was such a great man.

JJM Your father is quoted as saying, “Dream big, and make those dreams a reality.” Did this inspire you to pursue your career in acting?

DA Oh yes. When I was really little, he asked me what I wanted to be, and I told him I wanted to be a fireman. He said, “Dream bigger.” Another time he asked me what I wanted to be, and I said I wanted to be a princess, and he said we don’t have princesses in America. I told him in that case I guess I will just have to be a movie star, and every so often, he would remind me of that and ask what I was doing to achieve it. When I quit acting for a time to work behind the camera, he would remind me of my dream to act and say that when you let a dream die, a part of you dies with it. He was insistent on my pursuing my dreams.

So, right before he died, he moved me to Los Angeles, which I really didn’t want any part of at the time. I most wanted to remain close to him, to make dinner for him, to take care of him. But he told me that he had lived his life, and now it was time for me to live mine. And that is what I did. I moved here, to California, and he died the next year.

JJM Following the death of Dr. King, were people’s expectations too high for your father, particularly in light of Dr. King’s unparalleled charismatic appeal?

DA For whatever reason, people tried to compare the two of them. In a 1960 speech to the Montgomery Improvement Association, he said, “Let me set the record straight: I am not Martin Luther King. He is my closest friend and I wish not to be compared with him. Neither did I seek, nor do I ambitiously desire this high office.” The height of my daddy’s ambition was not to become famous, but to make world a better place for black people.

My father’s Grandpa George was twelve years old when Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and he would frequently talk to my father about the time when black people had the right to vote during Reconstruction. And then, he saw all those freedoms and liberties taken away under Jim Crow. He would talk to my father about the importance of rising up to do something about it. So, that is what my Daddy did. And in the process of rising up, he made America a better place, and he became a very famous man.

At my father’s funeral, Jessie Jackson said that if it is fair to say Martin Luther King was our leader, it is only right to say that Ralph David Abernathy was our pastor. He shepherded many great men, and helped shape their lives — and a better world.

.

___

.

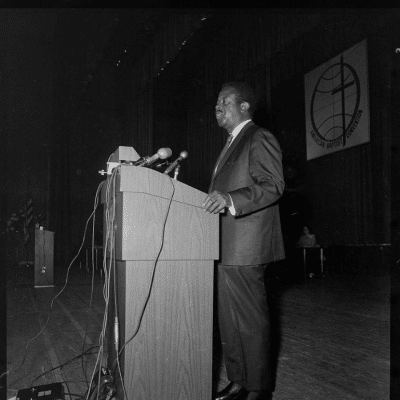

photo via Picryl

Ralph Abernathy, 1968

.

___

.

“Are you for Freedom tonight? I told you last night that I speak with authority. But these reporters don’t believe me. They think I’m just a rabble-rouser. But I speak with every Negro in 16th Street backing me up tonight. I speak with every Negro in Birmingham who is in his right mind, backing me up tonight. DO YOU WANT FREEDOM? IF YOU WANT FREEDOM…SAY FREEDOM! FREEDOM! FREEDOM! FREEDOM!”

– Ralph David Abernathy, speaking to the 16th Street Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963

.

.

___

.

.

Partners to History:

Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and the Civil Rights Movement

by Donzaleigh Abernathy

.

.

About Donzaleigh Abernathy

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

DA Oh my. I would have to say it was my grandmother, my mother’s mother.

JJM Why was she your hero?

DA My grandmother was three-quarters Cherokee Indian, and that was the dominating culture in her life. Even though she was my grandmother, her background was so entirely different from mine. I remember her as being a little lady who lived on an incredible farm of about three hundred fifty acres. When I visited her as a little girl, I was struck by the fact that for as far as I could see, everything belonged to my grandmother. According to Tuskegee Institute, her husband — my grandfather — had been the most successful black farmer in the state of Alabama during the forties. After my grandfather died, she lived alone in her big house with a gorgeous wrap around porch. It was absolutely heavenly. Visiting her was always an amazing experience. It made me want to grow up and be a nature woman like my grandmother, and have land, animals, and a big farm on which I could grow anything and take care of everybody with what I grew on the farm’s earth.

.

___

.

Donzaleigh Abernathy is the youngest daughter of the late Reverend Ralph David Abernathy. Born in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, she learned early on to face the challenges of injustice using the wisdom of nonviolence taught by Martin Luther King, Jr. Ms. Abernathy is also an accomplished actress whose credits include Gods and Generals, The Tempest, The Lifetime Series “Any Day Now,” Don King: Only in America, Miss Evers’ Boys, Murder in Mississippi, and the television series EZ Streets, Chicago Hope, 24, and Dangerous Minds. She is also a founding member of New Road Schools, which promote cultural, racial, and economic diversity. A native of the South, she now lives in Los Angeles.

.

.

This interview took place on February 19, 2004, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

* Text from publisher.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician (thank you!)

.

.

.