“Icarus,” a story by Ian MacAgy, was a finalist in our recently concluded 46th Short Fiction Contest. It is published with the permission of the author.

*

Icarus

by

Ian MacAgy

_____

Near the end of high school I thought myself sophisticated, a fan of Pink Floyd and King Crimson and Kevin Ayers, but at a Weather Report Concert in 1972 I had a nearly religious conversion. It was as though a stranger had run up to me and said, “hold this for minute” and ran off. Then the music exploded. I had never heard anything like this. Everything changed.

It was as though I grew hair in secret places and a new appendage. I became a different creature. After that night few of my suburban DC white friends’ guitar and lyrics-oriented ears could hear what mine could; the joy and heartbreak in this unfamiliar and ebonic timbre, this canvas painted in horn, acoustic bass, and polyrhythm; this blues, this brokenness, this homesickness.

There it was, though, for anyone who had ears for it—there, in the absence of verse, in the uncertainty and unpredictability of lengthy solos, in the timelessness of power beyond the moment from which music pulls meaning out of thin air, and lion and lamb both lie down together to listen.

One might think of jazz as pretty, or sophisticated, or hip—but those words tell of the appearance of a thing without its cost. Few of my school friends were motivated to listen, waiting, as I was, for the sound to become less foreign and to issue its invitation in tones and lines more clearly defined at each hearing, and more valued for the wait.

It was like the language of a new land in which I found myself, one no less beautiful or desirable as a result of words’ failure. Who knew what might happen? Just listen, and learn, I thought. One day I might find myself speaking.

Up until now my life had become defined by rapid transition, in the wake of school, my first love Julie, and drugs. I now found myself savoring a slow, growing familiarity as the music seemed to disrobe, an exotic older woman tantalizing my ear with her hide-and-seek mysteries, the sharp tang of sex mingled with incense—revealing herself as though through a mist, or a veil; rewarding only the one with sufficient leniency to hear her on her own terms. Jazz was a calling, a way of living, not just a style of music.

*

Alone in my graduating class, I foreswore the SAT exams. That Saturday I spent smoking reefer and drinking Boone’s Farm alone at the Washington Cathedral. I applied to no schools, spent no nervous days searching through the mail for the much-awaited and dreaded envelope. The truth was my high school grades barely qualified me for a diploma. In truth would have found it difficult to get in anywhere, except maybe one of the junior colleges in the area—in my case the chronically-on-probation Federal City College. So I was told in my one meeting with my faculty adviser during my senior year.

“Do you live in Montgomery County?” the adviser asked hopefully, looking regretfully at the wall behind me when I told her my domicile was in the District.

But I had heard my muse; her song of invitation poured through my open spirit like Spring‘s first breezes through a window thrown wide after a long winter, the scent of her promise like wisteria and jasmine, like cherry blossom and hope.

Accepting her invitation, I had become enamored and hungry, hovering over my basement turntable or sitting cross-legged and disciple-like on the lawns of the outdoor concerts that sprang up like squatter’s camps during the DC summertime.

Fort Dupont Park, Malcolm X Park—few white faces other than my own there, sometimes the Mall itself provided venues for the Great Names—Rahssan Roland Kirk, Horace Silver, Dizzy, Herbie Hancock—in the summertime. Summer in DC and its carpet of non-stop flowers; its odd admixed palette of freedom and fear now had a soundtrack.

*

My best friend Charlie was a jazz novice like me, blond and square-jawed, bearded, blue-eyed; habitually wearing rose-tinted aviator glasses, a suede Irish walking-cap, and a dungaree jacket. He played guitar, having saved up a summer’s salary from cutting lawns with his father’s landscaping crew to buy a white Stratocaster—like Jimi’s—and it was this he took from his home to the Sunday afternoon clubs and to my parents’ parlor where we jammed and rehearsed, plugging his cord into any empty jack on any available amplifier, emulating George Benson and Grant Green and Wes Montgomery; and not Jimi Hendrix or Carlos Santana.

Tea—his name was Timmy as a kid—played sax. Mostly a tenor player, he was forever experimenting, finding an old C-melody horn in a relative’s unused attic that he’d take, dented and out-of-tune, along to sessions. He was the product of an interracial marriage and one of three African Americans enrolled at The Georgetown School—two after a classmate named Heavy, recently addicted to heroin, dropped out in tenth grade.

Tea was tall, gangly, a string bean in dashiki and blue jeans with a wild and hard-to-tame Afro and wide, intense straw-colored eyes. In time he’d become a hard-core Black Nationalist, active in a Muslim separatist group with whom he’d participate in a brief takeover of the District Building in the late nineteen-seventies; and there he fired his shotgun into an opening elevator door, where a local radio reporter—and not the raiding and armed policemen he’d imagined—took the full brunt of Tea’s twelve-gauge double-ought shot shell and died on the way to George Washington Hospital.

But in 1974, still several years before that event, Tea was somewhere between the dark-complexioned white kid he’d been in childhood and the Muslim activist whose calling would be finally realized as an inmate imam in Lorton Reformatory years after his conviction. He was by far the most talented of the three of us.

*

We found a club on Fourteenth Street—I think it was Charlie’s brother Pete, who played bass— that held Sunday afternoon jam sessions in the Shaw neighborhood near the open-air drug corner of P Street. There, webbed in smoke and sunlight, perfumed with the smell of grilling half-smokes, reefer, tobacco, and old beer, we three wannabe jazz princes would go to indulge our fantasy of joining this fellowship of sad beauty.

At this storefront bar, optimistically named The Player’s Club, I’d stand on the stage with Charlie, Pete and Tea waiting my turn with trembling hands next to the piano, to sit in for one, two, sometimes three songs: standard pieces like “On Green Dolphin Street” or “Autumn Leaves,” painstakingly learned at home from a fakebook.

Like all neophytes, I flubbed the basics, especially at first. But with a teacher’s grudging patience, the older men allowed us to return next time, perhaps then to stay a little longer, maybe get a nod of recognition as we showed we’d worked some, that we’d learned something since last time.

The house bandleader, the pianist whose place I would take trembling in my turn, was a light-skinned and portly middle-aged man with a friendly, open face who laughed as easily as he spoke. He called out the tunes.

“What you want to play?” he might ask.

“ ‘The Man I Love’ in B-flat,” Tea might answer.

“Okay, except let’s do ‘All The Things You Are’ in E-flat,” he’d reply, and then count it out at an impossibly fast tempo, leaving us to catch up as best we could.

The bass player was darker-skinned; reserved and skinny, with a long face and high cheekbones. He wore the same threadbare gray-and-black sharkskin suit every week, slightly too large for him, as though he’d lost weight recently, over various open-necked polyester shirts.

His jacket lapels and sleeves would sway in rhythm with his playing, and he sucked in his cheeks and stared under his heavy brow whenever something caught his attention: surprised, amused, occasionally impressed. He never left the stage, and would stand next to Pete coaching him in subdued tones, occasionally playing along with him to model the technique he taught in these impromptu lessons.

The drummer was the youngest, perhaps in his mid-thirties, sporting a short Afro and wearing bell-bottom jeans and tank-top shirts that showed off his trim and muscular body. He spoke little and never directly to us, rather addressing any comments to the bandleader.

*

Tea knew someone who lived in a row house commune in Columbia Heights, off Fourteenth on Harvard Street NW, who’d let us come over to play, use his amplifiers, learn, and daydream. Charlie and Tea both had driver’s licenses, but none of us actually owned a vehicle, relying instead on one or another parent to loan us one when possible. Sometimes we took the city bus, loading double bass and guitar and saxophones and a sack of shaking and rattling light percussion instruments as the Metrobus swayed and braked across Irving Street NW.

A tall, lean, bearded, bronze-complexioned, balding, Afro-sporting man of about thirty named Prophet, Tea’s friend only asked in return for his hospitality that he be allowed to play his string harp with us when he felt like it. It was a strange sound he made, this man who liked to wear home-sewn dashikis—I remember in particular one with a red, black and green silkscreen silhouetted with a map of Africa; green inside a big red valentine’s heart which was surrounded by the black fabric of the shirt—and a hand-crocheted red, black and green skullcap that pushed his ‘Fro out at the sides.

Prophet was a droop-eyed, rhapsodic, black Harpo Marx-as-sad-clown, playing E flat arpeggios that sounded like blue stardust poured from a cup over the improvised chordal framework we offered from the song “Misty” that he usually asked for as his accompaniment.

And this was my life. I was waiting for something, but I didn’t know what at the time.

There were big name concerts whenever I could afford it, and I spent the meager funds I made cutting grass with Charlie’s father; with abandon on tickets, LP’s, and cover charges.

That year, I saw: Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Eubie Blake, Weather Report, Oscar Peterson, Ravi Shankar, Abdul Jamal, Keith Jarrett, Freddie Hubbard, Ornette Coleman (with Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Ed Blackwell, Charlie Haden), Bill Evans, Cecil Taylor. I saw Rahsaan Roland Kirk, David Murray, Charles Lloyd, Ella Fitzgerald, Pharoah Sanders, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Art Ensemble of Chicago, Paul Desmond, Betty Carter, Mercer Ellington, Egberto Gismonti, Nano Vasconscelas, Gato Barbieri, Art Blakey, Carlos Garnett, McCoy Tyner, Gary Burton. I saw Shirley Horn, Richie Cole, Gary Bartz, David Brubeck, Leon Thomas, Joe Williams, Sonny Simmons, John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Chick Corea’s Return to Forever, Charles Tolliver.

I saw stage lights and table lights and rums-and-cokes nursed through whole sets as ice melted in frosted glasses from the heat of the sound in the room. I saw beautiful women on the arms of dates whom I hated momentarily for the envy I felt and my desire, yet even their great beauty held no sway over me like Wayne Shorter’s minimalist phrasings or Cecil Taylor’s transcendence over everything I‘d ever known.

Whether in the park for free or for a five-dollar cover and two-drink minimum at Blues Alley, I was there. My ears trumped my eyes every time.

Melvin’s Black Tie, just south of Dupont Circle on N St NW was a well-maintained brownstone façade with guilt letters in a row of non-descript office buildings and historic townhouses. It was owned and operated by local dermatologist Melvin Leibowitz, a jazz lover and sometime bass player. Some said he bought the club because no one would play with him otherwise, like the kid who owned the only football on the playground.

This was too critical an assessment. Play he did, and not badly, with the group of local “all-stars” who made up his weekly lineup, assembling each Sunday evening to give some to the guy who paid the bills. Often I was there to check it out.

The all-stars were more-or-less the same group with a different headliner; or they’d all band together on those less regular times when Marilyn Cunningham stepped up to the mike and sang standards in her husky, lusty voice for the sheer joy of it. Richie Cole, the astonishing alto player who was a regular at the Black Tie before he moved out West and made records with his group Alto Madness, was always a special treat, playing his own “Tokyo Rose Sings the Blues.”

Every now and then, someone would show up from outside the clique of regulars. DC native Jimmy Hopps, on tour with Music Incorporated, sat in during a break in his tour, turning the usual rhythmic accompaniment on its head, stopping hearts with his polyrhythmic, everywhere-at-once solo, based on a five-over-four rhythm that started the solo and ended my limitations on what I thought a drum solo should be.

*

The Robert Andrew Wilson Group was another such surprise. It was a weeknight and I had only a few dollars in my pocket. I came alone. The group, like its leader Bobby, was from Howard University, where a quiet but serious jazz scene advanced, unseen except by those who were there. Donald Byrd and Andrew White III were on the faculty, and bands like the Blackbyrds, Horace Silver’s group, and the Jazz Crusaders took some or all of their membership from the student body.

The club was half-full, and the band was just assembling for their first set when I arrived. Bobby—Robert Andrew Wilson, whom I’d never seen before, looked up as I walked in as though he knew me. I took an empty table near the front and ordered a beer, feeling alive and only a little awkward—for what reason I felt either I couldn‘t say.

As always and even more then than now, my feelings took turns and twists for reasons beyond my ability to follow, but—perhaps only known to me in retrospect—somehow I sensed a journey unlike any other had just started, and my heart felt the anticipation.

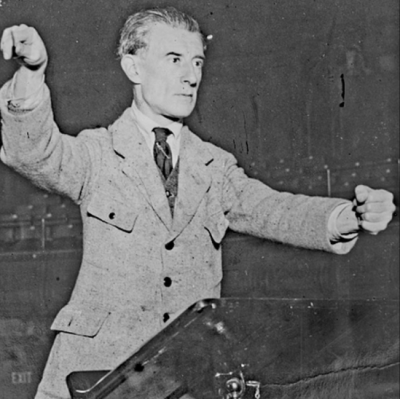

Bobby grinned like a man with God’s own joy in his his hands; controlled, frenetic, drumsticks flashing, rolling, trilling like digits appended directly to a great heart; caressing, coaxing, controlling the drum set, which seemed to tilt off its axis as though its eccentric rhythm changed the very center of gravity; coaxing a chain of concept from them, outlining but never directly stating the pulses that drove the sound.

*

Let me introduce you to the band: Leon Paoli played tenor and soprano, Dennis Redman was on alto and flute, Michael Harold (“Happy Harry”) Smith on keyboards—which included a synthesizer array upon which he’d programmed an eerie signature scale of eight equal divisions of a perfect fifth interval, which he would employ for many of his solos—fifteen instead of twelve notes to the octave—and on some of the melodies. Rudy Watkins and Billy Parker rounded out the group on upright bass and guitar, respectively.

The apparent adherence of this music to tonal rules was mere subterfuge. Passion, chaos, and spirituality lurked like phantoms in these familiar tonal corridors, which gave an effect very much like the music of John Coltrane or Albert Ayler. You could hear it: the straining of the spirit in its long exile; as though from “Out of This World” from Coltrane’s Live in Seattle record, or Ayler’s “Prayer”; while the sound was like something from Miles’ Sketches of Spain if it was interpreted by his band from Bitches Brew.

Listening to the group was like walking down a circus hall of mirrors, the distorted images of one’s own reflection a corps de ballet dancing along the walls. One enters a museum of one’s own experience, its manufacture entirely of sound. The reflections are real, but changed by the immediacy of time and space. Snatches of nursery rhyme, blues, and Philadelphia doo-wop filled their ad lib songbook, and among these touchstones of memory and shared culture became to the listener a ground of reflection, exploration, and surprise.

Like Gil Evans, like Mingus, like Ellington, Bobby concerned himself with the integrity of each individual line in the arrangement, not just how they sounded together. Bobby knew that shepherding sound requires attention not only to tone and timbre, but also to the humans who made it. The combining of dynamics, harmony, instrumentation, and technique in order to affect this sound was magnificent. You could hear Ellington back in there, Fletcher Henderson, even Louie Armstrong and Kid Ory, if you had ears for it. And Robert Johnson, George Clinton, Bird; Clifford Brown, if you had ears.

At a certain point, I no longer could be sure of what I heard. I could hear emotion, the sound of its waves against the beach of consciousness, the slow sound of truth in long, ponderous, and rolling inexorability breaking on the soul’s shoals.

Perhaps this is the outcome of this thing we call love as shown in art, in this fundamental level of detail, where more casual effort might fail or be ignored: that love so sown would emerge again through the effort of many; magnified many times over in the sound that came finally and with such great beauty to the listener’s ears. Not mere sound, you understand, but love.

But, of course, it was sound, improvised and written, sound that was gone as soon as it was made, The room, the listeners, the blackness of the night outside; the subtleties and nuance of each moment are lost, forever, as soon as they appear, just like each moment in which we live.

But far from futile, they matter in the deepest possible way because in each coalescence of note or chord or texture—or perception—there is a unique opportunity for each one, performer and listener alike, to experience that transcendent human moment we all know, instantly, as soon as we come upon it, as art. I was changed there, in that transcendental place…maybe validated, maybe even less alone, having shared with the ensemble and its other listeners that night in the primordial act of creation.

*

There is a photograph of Bobby I used to have, a publicity photo. I kept this one for a long time, until in some left-behind box I lost it long after my ordination. He stands in profile, his coffee-colored skin darkened somewhat by the black-and-white medium of the film, his hair in a medium-length Afro. A leather jacket—brown, I remember that jacket well—hangs off a shoulder, and a long stare frames his countenance. He looks so young, gazing off into some profundity. Bobby was always on the verge of laughter, his smooth features unlined by any hint of worry.

A huge tree, blurred, in the background, branches white and laden with ill-defined flower, formed a halo around his head.

Oh, that Wednesday night at the Black Tie I trembled with unaccustomed emotion as the first set came to a close. I thought I’d come cool to this joint to nod my head, tap my toes, to hear variations on the workingman’s riffs I’d come to know that year as they became my own. I didn’t know I’d come to one of life’s starting lines, stumbling and shivering, and that hereafter I would run, or not move at all.

After the first set, Bobby surprised me by coming over to my table and sitting down, pointing at the pack of Kools on the table in front of me. My mind was far-off, displaced, wandering some secluded and foreign idea; my eyes wide and focused on some distant point; my mouth an “o” of contemplation, no cool nod of greeting now. I would learn later that Bobby rarely smoked, once in a while after a particularly significant event, or when he embarks on a new course in his life.

Tonight, it would turn out.

“Go ahead,” I said, blushing.

“Thanks for coming out, man,” Bobby said, his voice smooth and pleasant, pointing with a nod at the book of matches in my hand, his smile dazzling beyond any light, of match or sun, “What’d you think?”

“Yeah man,” I said. That and a nod was all I could manage, my voice a croak, like a frog, as I struggled into some semblance of composure, as ill-fitting and difficult as leather pants left out in the rain. My hands trembled as I handed him the matches. I dared not light one for him, for my fingers would betray me, and even I wasn’t yet ready for their knowledge.

Had I met him somewhere before? I wondered. He acted like he knew me, but surely not! I’d never have forgotten that face, so full of life and kindness that even then I would have described it as beautiful.

“You guys been together for long?” I finally asked.

“Yeah, well, we’re all at Howard.” How-what, he pronounced it, his Louisiana drawl out of place, like his presence at my table.

“It’s a small program, Jazz Studies; you kind of get to know each other pretty well.” Bobby smiled again, “But, yeah, man, we play together a lot. It’s like we have to, you know? We work hard, we sometimes can’t stand like even one more second of each other, and then, like, we got to get right back to it.” He shrugged, giggling and grinning playfully, “You play, man?”

Even my most optimistic fantasies wouldn’t equate what I did with what I’d heard tonight.

“I try, man, but I’m just starting out, you know?” I replied.

“Yes, brother,” he said, “we all gotta start someplace.”

I nodded, my head like the bobble-figures you see in cars sometimes. We spoke for a few more minutes. I no longer recall what we said.

“Look—here’s my number.” he said, scrawling it on the back of the matchbook I’d handed him earlier. “Call me, maybe you could come by and check out a rehearsal or something. I’d like that.” He smiled like he meant it and I was rocked back on my heels. “I’m up in Mt Pleasant.”

*

The strange rumblings in my heart that night had no context, as though the center of the earth was tearing along some fault line I never noticed before. Was it joy?

As it was, I bounced, floated—whatever it was, it was not walking—along the streets later that night, choosing the long, meditative way home up Connecticut Avenue after the last set rather than a cab, a bus, or a flop at Charlie’s house over on Seventeenth Street as I often did after an evening at the Black Tie.

By its end, and even though they remained hidden from me, my choices were already made. The sodium lights along the avenue gleamed like amber jewels and the night wrapped me up like a satin sheet against the bareness of my skin. It was a night of gods, of Olympic congress, of great balls tossed like balloons from hand to unseen hand in a realm I sensed but I could not see.

I lit a joint after I passed Florida Avenue, the walk becoming steeper. The Washington Hilton, its white façade lit and its entryway alive with cabs and doormen and the air of importance even at this late hour, seemed in league somehow with an inner destiny I could not quite fathom.

I was pregnant with power and fate. Somewhere above I heard laughter, celebration, and the inebriation of spirits whose wine tippled upon me like rain on the earth below. I felt its taste upon my tongue—a tingle and a warmth, there and in my fingertips, in my loins and along the chain of energy within, which the Yogis call chakras. I was aflame with strange fire, and in abandoning myself to the freedom of my own extinction I never felt so alive.

_____

Ian MacAgy is a physician in public health OB GYN practice in Northern California. Prior to pursuing his medical studies he was a musician in the Washington DC area, having studied at Berklee College of Music and the Creative Music Studio. “Icarus”is his first publication, adapted from a larger work still in progress.

Great story! I grew up in the D.C. area & lived in Mt. Pleasant when I was in school. I’m not a musician, but D.C. is a fantastic town for all kinds of music.