.

.

.

The Graystone Ballroom

4237 Woodward Ave.

Detroit, Michigan

.

_____

.

On February 27, 1922, when dancing in giant ballrooms was wildly popular, Detroit’s Graystone Ballroom – a block long structure on Woodward Avenue — opened with the All-University Ball.

According to Dan Austin of HistoricDetroit.org, the property’s original owners were planning a ten story building that “was to house a restaurant called the Chinese Gardens,” but the owners ran out of money before it could be constructed. Enter Detroit bandleader Jean Goldkette, whose investment and vision created an entirely different experience.

In addition to leading a famed Detroit orchestra, Goldkette — who studied piano at the Moscow Conservatory as a child prodigy before his family emigrated to the United States in 1911 (he arrived in Detroit in 1916) — was prominent in the entertainment business during his time, being principal in Jean Goldkette Orchestras and Attractions, which worked out of Detroit’s Book-Cadillac Hotel.

While 20 bands worked under his name during the 1920’s (one was known as the Eskimo Pie Orchstra), the most prominent recorded for Victor from 1924 – 1929, which at times included Joe Venuti, Bix Beiderbecke, Hoagy Carmichael, Frankie Trumbauer, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, and Eddie Lang – a band called by Fletcher Henderson band member Rex Stewart as, “without question, the greatest in the world.” (To understand the quality of this ensemble, Goldkette’s orchestra once defeated Henderson’s at a Battle of the Bands concert at the Roseland Theater in New York, 1927).

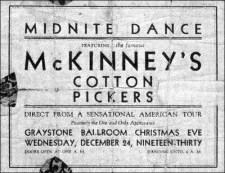

Unfortunately for Goldkette (and for those in the orchestra who went without their paychecks), in 1927 he was unable to pay his musicians, offering Paul Whiteman the opening to hire them away. Subsequently, Goldkette had a hand in putting together other bands, including McKinney’s Cotton Pickers. (which became one of the premiere African American jazz groups) and Glen Gray’s Orange Blossoms, (eventually known as the Casa Loma Orchestra, one of the era’s top dance bands).

The Graystone’s ballroom, Austin writes, “was huge, with room for 3,000 dancers — 4,000, it was said, if they danced close. Couples would waltz under a 60-foot-high domed ceiling, or they could take a breather and watch the action from a balcony that ringed the dance floor. Elegance was everywhere, from marble staircases and hand-carved railings to a circular fountain.”

The Graystone — much like every Detroit ballroom of the 1930’s — was racially segregated. Many of the performers were African Americans (allowed to perform nightly), but, according to Kim Clarke, whose “Backstage at the Graystone” is a terrific history of the property, African American patrons “were allowed into the ballroom only on Monday nights.”

The space was exciting for its dancers, employing impressive lighting techniques. Before its opening, the Detroit Free Press reported that “color changes have been worked out so that with the use of spotlights and floodlights, many unusual and beautiful lighting effects can be obtained during dance numbers. Beauty, grace and dignity are the first impressions received from a visit to the structure. Little conveniences and comforts are discovered at every turn.”

*

“The ballroom was immensely popular,” Austin writes, “and many jazz greats took to its stage, including Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie and Guy Lombardo. McKinney’s Cotton Pickers and Jean Goldkette’s Orchestra became nationally renowned while playing at the Graystone. Benny Goodman, heralded as the King of Swing, said he once drove all night from Chicago to see the legendary Bix Beiderbecke when the coronet player was part of the Graystone’s house band in the 1920s. Some have called the Graystone Detroit’s ‘cradle of jazz.’”

“The ballroom was immensely popular,” Austin writes, “and many jazz greats took to its stage, including Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie and Guy Lombardo. McKinney’s Cotton Pickers and Jean Goldkette’s Orchestra became nationally renowned while playing at the Graystone. Benny Goodman, heralded as the King of Swing, said he once drove all night from Chicago to see the legendary Bix Beiderbecke when the coronet player was part of the Graystone’s house band in the 1920s. Some have called the Graystone Detroit’s ‘cradle of jazz.’”

The depression caused financial challenges for Goldkette, who in 1935 filed for bankruptcy, leading to the purchase of the building by the University of Michigan, whose tenants attempted to keep the venue alive with the continuing presentation of jazz music. But, in the face of falling interest in jazz and ballroom dancing, after 25 years, the rent finally went unpaid, and the Graystone became a place for R&B acts, including Detroit legends Jackie Wilson and Little Willie John. Ultimately, Motown founder Berry Gordy, Jr. bought the Graystone c. 1963 for $123,000, planning to “run it as a supper club and host ‘Battle of the Bands’ competitions,” Austin writes. But, Motown’s massive success rendered the Graystone obsolete (wasn’t big enough and its infrastructure was inadequate).

“When Motown abandoned Detroit for Los Angeles in 1972, the Graystone’s fate was sealed,” Austin writes. “In the early 1970s, a fire next door damaged the Graystone’s roof. The ballroom’s broken windows and general state of disrepair were an open invitation for vandals to descend on the building. With Motown firmly established in Los Angeles, the Motor City was an afterthought, and the Graystone quickly became a real eyesore. Not even its legendary marquee remained to mark the spot of so much Detroit music history.”

*

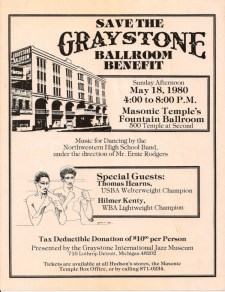

For a time, Austin writes that “James Jenkins, a retired streetcar and bus driver, founded the Graystone International Jazz Museum in 1974. He dreamed of saving the landmark and turning it into a museum. By the end of the decade, however, Motown announced that it would level the old ballroom.”

For a time, Austin writes that “James Jenkins, a retired streetcar and bus driver, founded the Graystone International Jazz Museum in 1974. He dreamed of saving the landmark and turning it into a museum. By the end of the decade, however, Motown announced that it would level the old ballroom.”

.

Following several unsuccessful local attempts to save the building, it was wrecked on July 19, 1980. “This corner had hosted countless jazz legends and many of Motown’s brightest stars and was home to countless memories of tangoing and twisting the night away. Today, it is home to only Big Macs and McNuggets; a McDonald’s restaurant now occupies part of the site,” Austin concludes.

.

.

To read Austin’s complete excellent article on the Graystone, click here.

To view an extensive data base listing the bands who played the Graystone (and the event dates), click here.

To read a more comprehensive history of the Graystsone, “Backstage at the Graystone” by Kim Clarke, click here.

.

.

(A postscript…Jean Goldkette ultimately left the jazz business in the early 1930’s, working as a booking agent and classical pianist. He moved to California in 1961, and died at age 69 the following year).

.

____

.

“It was a spectacular space. A domed ceiling soared five stories over a sprawling dance floor designed to hold 3,000 people and which, in the years to come, would see nearly twice that many crowd onto it. There was a stage for musicians, a state-of-the-art lighting system to cast color and mood, coat rooms, rest rooms and smoking rooms. A balcony ringed the dance floor, with lounge chairs and divans, and a large mural above the stage depicted an old English hunting scene.”

-Kim Clarke, from “Backstage at the Graystone“

.

.

.