Publisher’s Note: The publication of Arya Jenkins’ “HEAT” is the fifth in a series of short stories she has been commissioned to write for Jerry Jazz Musician. For information about her column, please see our September 12, 2013 “Letter From the Publisher.”

For Ms. Jenkins’ introduction to her work, read “Coming to Jazz.”

_____

Ms. Jenkins introduces “HEAT”

“HEAT” is a story set in modern times that is meant to convey the pulse and fervor of hot blues, and that echoes in its script, the storyline of some of the lyrics of tunes of the period, some of which are interspersed throughout as headings.

I intentionally wanted to move toward something both new and experimental in this story — which is not about jazz or the blues, although the music and ideas about it thread throughout. The exaggerated characters, fast pace, intensity of emotion, high drama, all of these are elements of hot blues lyrics as well.

I would like to thank Editor/Publisher Joe Maita for his open-mindedness and encouragement regarding the experimental narratives he has commissioned me to write for Jerry Jazz Musician. It is a writer’s dream to be allowed to stretch her own boundaries, and I am truly grateful to be supported in that enterprise.

__________

“Heat”

by

Arya Jenkins

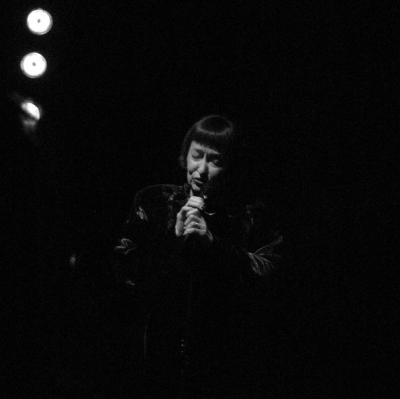

1. Savoy Blues

Mercies would have put blues on the menu if it could, but that was a province of the kitchen, where I worked four and a half months too many. I heard actual blues music and caught a gust of air conditioning whenever I snuck through the dining area early in my shift to use the guest bathroom before customers arrived, passing the line of booths next to the orange and black walls on which hung colorful modern paintings of jazz musicians and the shiny oval bar at the restaurant’s center that was as cool, slick and neat as the kitchen was hot, mean and funky. As I hung over the toilet, pissing the hot, bitter pee of someone who drinks too much coffee and has too much stress, I let the music of Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Louis Armstrong seep into me like a balm. Sometimes my sneakers did a one, two, before I hoisted up my jeans reminding myself: That’s your enjoyment for the day, sister. Get ready, it’s time to go to hell.

Once the ticker tape with orders started rolling in, you forgot about everything but popping wings or whatever into the fryers and getting orders out quick without burning yourself too bad, and plating everything nice and neat. Once we got cookin’, you didn’t think about your kidneys or anything else, you just stayed focused. If you forgot to tuck a Styrofoam cup full of something iced at a corner of your station to stay hydrated, you might be shit-out-of-luck. Even with a cold drink nearby, you rarely had time for a sip. Even when it wasn’t crazy busy, the manager was always on your ass to do something — as if we didn’t have enough to do already, as if putting up with all we did and making $8.50 an hour at it was stealing from the establishment.

The prep gals at Mercies put together soups, chili, mac and cheese, deviled eggs, potato salads; assembled tomato beds and prepped fried green tomatoes down in the basement. They did the stocking too, hoisting huge sacks of flour, rice and sugar onto high shelves and lugging 50-pound cans of oil and hefty pots full of greens or whatever upstairs to the dark, narrow kitchen. After working their butts off all day, they went home to kids and husbands or boyfriends, and did the same shit all over again, only in smaller quantities.

I’ve been cooking professionally 20 years, starting out prepping at a restaurant in Georgia after Arliss left me when Sally was two. As far as kitchens go, things haven’t changed a bit in that time. Women are still bitches and scrubs where men are concerned.

2. March of the Hoodlums

The hoods I worked with at Mercies got treated like royalty. They slouched in late, droopy-eyed, nasty-tempered, more hung over than you would imagine it was possible for a human to be, itching to argue, looking half the time like they’d slept or passed out somewhere seedy in their black uniform jackets and stained checked pants.

I expected management to get on their asses for their being late or looking like shit, or for their attitudes, but no such thing. The manager Abel couldn’t wait to pat them on the back and call them a rock star in the kitchen.

I was the only female upstairs working the fryers next to these guys who were scrawny, toothless young druggies and overweight ex-cons, off the wall, all of them. Second night on the job, two of them got into a fistfight, due to one owing the other money. The older one quit and got hired back the next night after the one who had stayed, whose girlfriend had just had a kid, got fired. Day after that, the one hired back was sent to the emergency room with heart issues, forced off his feet for a month and therefore off the job — at 31. Typical kitchen drama.

Bottom line is you don’t take a restaurant job in Stokesville, Ohio, because you want to join Top Chef, but because you’re desperate. Restaurants attract people who can’t get hired anywhere else, ex-cons whose records don’t matter in a kitchen, or women who only know how to have kids, take orders and cook. Some of us, however, don’t take shit, even if it looks like we might. We stay quiet, don’t talk unless spoken to, and hope somehow to stay under the radar of our whacked-out bosses while doing our jobs.

Stress is constant. You have to put orders out fast without a fuss, fix problems in seconds, act like everything is cool all the time. But working in heat and under duress turns people into all kinds of monsters. It made the guys I knew horny as hell, although you might have thought a good look in the mirror would have humbled them.

3. Chasin’ the Gypsy

Some grabbed their crotches when they saw you, or smacked your booty when you passed by. One or two got in my grill and asked whether I was “giving my gravy.” If they had balls, they asked you out, and of course then you had to find an excuse. “No, I’ve got a hot date with King Kong after work, no can do,” I told Lenny once. Long as you had two legs and arms, and your own teeth, you were up for grabs at Mercies.

I was the only woman working in the kitchen at Mercies, and I was the only woman with my own teeth. All the others, younger than me, wore false sets, or none at all as their sets didn’t fit. Some days, the ladies in the basement looked like a bunch of grannies. Fact was, some already were, at 41 and 42. It wasn’t only poverty that had got to them, they had more kids than me, had been married longer, and so were naturally worn out.

Jackson claims I winked at him first time I laid eyes on him, the afternoon I was led into the kitchen and introduced to the crew. He might be right about that. I was in the mode after all, wearing a tight blue dress, my hair down for the job interview. I remember Jackson poking his big black head under the shelf where the orders are placed, welcoming me with his sly mug, and, after pushing his glasses up at the bridge with his thumb, turning that same thumb up to his buddies, a signal I was “in.” Abel spent most of his time hiring, as staff quit all the time, although you pretty much had to set fire to the place to get your own ass kicked out.

I was very deliberate wearing that blue dress, letting my hair down and putting in my contact lenses to make sure I looked as attractive as possible. I needed the job as I had just walked out on a gig a little further down the pike along Route 422. In this industry, you not only live paycheck-to-paycheck, you try not to talk about where you’ve been. It’s just bullshit to managers anyway, as they only care about how you perform for them. Anyway, I let my hair down to get the job, but once I got it, pulled my hair back into a ponytail, put my glasses back on and my hard side up. Jackson always looked at me like I still had that blue dress on, like he knew what was hiding underneath my apron and would one day unravel my secret. I had to smile to myself at that.

When I first met Jackson, he still had a black box around his ankle, which he lugged around like a ball and chain, as he was under house arrest. You saw guys with black boxes around their ankles all the time working in kitchens. But Jackson was polite, which I immediately respected. On account of this, I listened to him and went to him whenever I had questions. Sometimes, if a lot of orders started coming in, he would help out, tossing shit for me into the fryers, putting his hand on the small of my back as he went around me, respectfully helping me get orders out at my station. That sort of thing I found very attractive. He had other nice habits too. Like, whenever I ran outdoors to check my cell phone before Chef came in, or whenever I clocked out, Jackson would always follow me out, lighting a cigarette while hanging over the banister just outside the back door, watching me get into my car, as if looking out for me.

4. Wild Cat Blues

Once in a rare while, when the weather was bad and it rained like monsoon season in India, it got slow at Mercies. Those times, the guys I worked with all huddled next to the dumpster out back, shivering while sharing a joint like it was winter while I took the watch indoors waiting for orders to come in — I myself not being a doper and having no inclination whatsoever to visit a jail, especially after what the guys had told me they’d experienced. Chef Randy didn’t give a shit about the extra curricular activities as he himself was a doper, but Abel would have had a hissy fit.

Most of the time, I worked next to Lenny. Tattoos of snakes, scorpions, eagles and skulls covered every part of his body from his neck to his ankles. He was artistic, having designed some of the eagles and skulls himself, and liked to show off his designs, some of which were in intimate places, and each of which had a story. Across his fingers in ornate lettering was tattooed, Son of Satan.

Lenny had been in prison too, had spent three years in some hellhole after being caught driving from Chicago to Pittsburgh with 50 pounds of pot in his car. When his windshield wipers stopped working in the rain, he pulled off the highway, and a cop spotted and took him in. Lenny said, “If you smoke and are a young male driving a shitty car, cops will check your vehicle.” He got seven years for that, but only did three, getting out on good behavior, he told me. Lenny was 33 going on 70. I never questioned his lack of sanity, just nodded at whatever he said. He had a crazy streak in him a mile wide that you would have had to be blind not to see.

It was Lenny gave me the recipe for how to make hooch out of orange juice, like the men do in prison, and how to tattoo yourself with a staple inside a pen and burned Vaseline that turns into soot that you scrape off a piece of cardboard after you burn it. I said to Lenny, “All that self tattooing must have been painful.”

“When you’re alone all the time, you got nothing better to do.”

Man, I thought to myself, you could have read a book.

I hated Lenny first time I saw him. He looked like he’d rolled all night in mud deep in some woods. Sucky attitude too. My first weekend shift on the fryers, they put Lenny to work with me, and right away he got to talking big, or what he thought was big, bragging to me how he spent all his day every day shooting “whatever I can find” in the woods with his gun.

I’m a meat eater and don’t deny it, but don’t talk to me about shooting critters that have done nothing to you then act like you’re a big man for doing it. That’s just bullshit. I struck a big “X” over Lenny in my head when he started talking like that. It wasn’t enough for him to gab about shooting things, he pulled out his buck knife from a sheaf at his hip, and showed us how nicely it cut through meat, like butter. His hands were big and so familiar handling that knife slicing raw meat, it sent a chill through me. Whenever he snacked on anything, he pulled that thing out to use as utensil. I didn’t like it one bit.

Anyway, my first night working with Lenny, he could tell right away I did not like him, as I would not look at him. He got back at me taking over when we had an order so he did all the frying and plating, but when it got to be real hell in the kitchen with a dozen or so orders coming in at once, he just disappeared, like for 20 minutes at a time. Next day, when I complained about him, Abel just told me to let it slide. Turns out, Lenny was one of the biggest rock stars at Mercies.

Besides Jackson, the only other dude I could tolerate was the dishwasher, a huge gentle giant named Lester, whom we called Samson, Sammie for short. Sammie’s ex-wife was a big drunk with a long list of DUI’s, so Sammie was raising their twin girls, Samantha and Julie, who were five. What a peach that Sammie was. He carted the big boxes of goods that came in trucks to the cooler, took out garbage, and swept up too, in addition to what has to be the hardest job on earth — washing restaurant crap. He had the saddest eyes, but always kept a smile on, even while working like a dog, his tee soaked through with sweat. I felt bad for Sammie and would sometimes cook him a side of wings or slip him some fried bacon in a bag, whenever Abel wasn’t looking.

Sammie’s niceness and Jackson’s attentions balanced out the sheer terror I felt sometimes working next to Lenny, who was a time bomb just waiting to go off. You can’t trust people with dead eyes, which Lenny had. I was so intent on seeing the good side of everybody, I almost forgot about those dead eyes.

In order to get along with everybody, I finally made a point of looking at Lenny, noticing his down-turned mouth, his feet that turned in, and the sadness he wore like a weight on the lonely hunch of his shoulders. Then I started being a little nice to him, patting him on the shoulder, shooting him a compliment now and then over the way he handled burgers and ribs. He had the strongest hands and would press down on meat so hard with the steel spatulas to make it cook fast, his burgers actually spurted blood. One day, Lenny confided to me he liked cougars, me thinking like an idiot he was referring to tigers, not realizing until later than night while deep into a book that he had been referring to me, an older woman, a “cougar.” So then I told myself to temper my compassion, even though I could see I was now on his good side.

5. Keep Your Temper

Chef Randy joined us about a month after I’d started at Mercies. He was a real dick, but as he was taking over after a long vacuum, he was given a lot of leeway with us. His first day on the job, he ripped into a young kid who was using too much pepper on the sides of beef he was massaging downstairs, so the kid and his mother, one of the prep ladies, told him where to go by not showing up ever again after that. What idiot introduces himself to staff that way.

Truth was, Chef Randy was a drunk and addict who would spend the first 20 minutes of every day in the bathroom getting high. You never heard a toilet flush, so there was no mystery about what was going on. One day I went in after him and saw a white spray of dust on the sink that was definitely not soap. Most of us had been there or in relationships with people who used, so we knew we were up against trouble with a capital “T” with him. He was so full of himself, walking in late, always sucking on a can of Coke, always propping it somewhere that it would spill, always blaming somebody for his mess. He acted like his real job was to criticize everybody, but when he got angry and authoritative all you noticed was his Faux Hawk hairstyle bobbing like a Baby Huey, making him look ridiculous, laughable even. Still, we all knew better than to cross him.

I stayed out of Chef Randy’s way but was always torn between trying to be nice to the guys I worked with that I found hard to like and turning my hard side up to them because these guys didn’t know what to do with niceness except fuck it and that wasn’t going to happen. Finding a balance wasn’t easy. There was nothing simple about my relationship with them, or their relationships with each other either.

Jackson always acted like a friend, but didn’t miss a beat where Lenny and me were concerned once Lenny and I had turned the page on our initial dislike of one another. At first, it was kind of cute, sensing that extra current of possessiveness and jealousy that got going between them over me. The minute I started paying attention to Lenny, he would be all over me, trying to help me out his way, repeating with his slow drawl, “Y’all have to do it like this,” showing me how to do shit like I was a newbie. He would really get into that when the kitchen was slow, abandoning his station and sticking to me like glue, and it occurred to me that was probably the way he courted. One day, Jackson got bored watching this, and started acting like a porpoise jumping up and down behind Lenny to catch my eye. That cracked me up, so I started tossing him fries that he caught in his mouth. He actually caught them. I could feel the heat of Lenny’s ire next to me percolating over that, but I didn’t care. I wasn’t married to either of them. Besides, if I was going to work my ass off at a thankless job, I was going to enjoy myself doing it, whenever I could. After the game was over, Jackson sidled up to me and said, “You know in the blues, food means sex, like offering your cabbage and shit.”

“Yeah and you prefer French fries,” chimed in Hector, a Latin waiter with slick black hair and a favorite orange shirt he liked to wear who was an expert in overhearing everything. “Ha ha ha, ha ha ha,” Hector began banging the back of his round tray like a drum. “Anybody want to try my cabbage? No, I’ll take your French fries. Ha ha ha.”

“Fuck you, Hector. You nothing but a mambo queen,” Jackson told him. Hector did a samba, heading out of the kitchen, still beating the drum.

Those two, Jackson and Lenny kept different kinds of eyes on me. One day, I took off the rubber band around my ponytail to adjust it and saw Lenny crane his neck, taking in the sweep of my hair, which I could see brightened him a little. Jackson on the other hand was vigilant, a protector, even though I always felt that was the way he hoped to get to me. Even an ordinary man can turn into a genius when he makes up his mind to win over a woman. And sometimes, even a smart woman who knows the score can act like a fool.

6. Back Door Man

Like so much in life, everything boiled down to what happened one night, one event that determined all our futures. It was early fall between the lunch and dinner shifts and we had the back door open, letting in breeze while Jackson and I danced to Muddy Waters’ “I Got My Mojo Working,” which the bartender Alec had turned up for us. Jackson was going around kicking up his heels while pretending to play a guitar behind the counter. I laughed as he skidded onto his ass on some grease. He cracked up at himself, got up and kept up his performance. Then Lenny showed up, looking pale, wearing his mean snake eyes. I watched Lenny strut over to the register to clock in, then head downstairs to grab his coat. In a minute he was back, coming around behind the counter with a fistful of bags of burger buns that he thrust into a shelf under his counter and frozen burgers that he stacked inside a cooler drawer under the stoves. He nodded at me. I nodded back, took a sip of my iced tea and went back to watching Jackson, who was singing: “Got my mojo working, but it just won’t work on you/I wanna love you so bad till I don’t know what to do,” while Lenny stared straight ahead ignoring all like he was just waiting for something.

“You think you are some hot shit, man. I bet you thought that in the joint too,” said Lenny.

“Got my mojo working

But it — uh uh — just won’t work on you.”

“Aw, let him be, Lenny. We’re just having a good time.”

At which point, Abel came around hollering orders, “Is that pork ready. I need to have somebody pull the pork. Lucille, is your station ready to go for tonight, we have a couple of big parties coming.”

“I’ll pull pork, boss. I’m all set up,” said Lenny.

“Hey, man,” Abel came around to Jackson and put his arm around him, “Go wash the sweat off your face, buddy,” and again, “We have two parties of 10 at six tonight.”

I went downstairs, taking my time getting a couple of extra sacks of sweet potato fries from the freezers before coming back up. I could hear the ticker tape starting as I climbed the stairs.

“Pork fries,” Lenny called out, so I popped some into the fryers figuring we were getting started early that night. The clock over my head read five-fifteen.

I hauled out the fries, seasoned them, poured them into a basket, went to get four ounces of pulled pork and was sprinkling that on as Chef walked in, his face red from drink and possibly wrath as he watched me garnish the pulled pork sauce with bits of greens and bacon.

“What are you doing with pulled pork fries. I ordered a sandwich.”

“That was you, Chef?” said Jackson, who ran the sandwich station. “Why didn’t you say so?”

“I said so. It’s on the ticker tape. Pulled pork sandwich. Hello!!,” he looked at me. “Can’t you read.”

“I called it out,” said Lenny quietly.

“Pulled pork sandwich,” Chef yells at me again, even though the sandwich department is where Jackson is standing on the other side of Lenny, even though Lenny called out “pulled pork fries.”

I shrug.

“What are you, hard of hearing? Dumb?” He yells at me again, and I feel myself blushing.

There was no mystery to Chef’s outburst. I knew what it was about. After grease from the fryers had wrecked my glasses that cost me $650 dollars, searing the anti-glare layer so it looked like I was seeing through snow, I asked the accountant in the office downstairs whether she might talk to Chef about having management help pay for a new pair of glasses, or even goggles to protect what was left of my glasses. She must have talked to Chef right away because that same day, the day before the one I am telling you about, he came right up to me, spraying his vodka breath on my cheek at the peak of the lunch hour while I was juggling several orders. “Grease from the fryers didn’t do that to your glasses. That grease doesn’t have preservatives. There’s no way the grease did that to your glasses and no way we are paying for it.”

Until that moment, everything that had happened at Mercies — from fights between workers to squabbles over orders — had happened at arms’ length, not really to me. My glasses getting ruined was in my face, literally. And Chef getting in my grill about it was just plain wrong, and I let him know it.

“First of all,” I said, “Of course this grease has preservatives. Secondly, whether it does or doesn’t has nothing to do with the fact that hot grease splattered my glasses and ruined them. Thirdly, since you don’t believe this hot grease ruined my glasses, I will have the doctor at the eye store call and explain to you exactly how it happened. Tell you what, I don’t want to talk about this right now. Bad timing. Why don’t you just get your face out of my face and stick to what you know.” With that, I kind of waved him away with my left hand.

Until that point, I had not spoken more than two words at a time to Chef — “good morning” or “good night”, and “yes chef,” or “no chef.” Until then, Chef Randy might have had the idea I was a meek woman doing my job the way he wanted me to do it, and would never have to worry about me. After my small tirade, he went away quietly, but I knew when I saw him the next day, the day that everything happened, that he had murder on his mind where I was concerned and would be out for my blood. So that’s what his yelling at me was really about. Payback.

“Hey, you deaf or what,” he yelled at me again.

I was that kind of red that grows steadily and threatens to combust if nothing hinders it, while trying to stall my mind, which was telling me to just “go, go.” But I had done that already somewhere not long ago, and I wasn’t ready to leave Mercies.

“Hey Chef, I just said I told her ‘pork fries’,” said Lenny.

“I don’t give a shit. Shut up, meathead.”

“What the fuck,” said Lenny under his breath. I could hear him huffing and puffing. “Nobody calls me that,” he shook his sad head.

“She’s the one who did the order.” Chef pointed at me like I was running from the scene of a crime. A part of me was starting to laugh a little inside seeing I had an ally, somebody I hardly expected to be there for me under such circumstances. It kind of tickled me.

“No need to talk that way. No need,” said Lenny.

“Hey, meathead. If I want your opinion, I’ll ask for it,” Chef said again.

At which point, Lenny reaches for Chef’s coat with his left hand, pulls him forward on top of the shelf where we planted orders, reaches back with his right hand, and simply, like it’s something he’s done plenty, plunges his buck knife between Chef’s eyes, turning it once to the right before pulling it out. He wipes the blade on his coat, then takes it off and drops it before heading out. Chef jerks back, hands wild and quivering, eyes bugged like an animal watching its own slaughter, blood spurting everywhere, and drops jiggling in his own juices on the grimy floor just as Lenny disappears out the back door. Then Jackson runs around the counter calling out, “911, call 911,” although, of course, it’s too late for that. The waiters and bartender are now hovering over Chef Randy, hands stifling their mouths, while I stay frozen trying to remember what it was happened, what it was that was said, my mind a speeding train, going I don’t know where.

7. Baby Please Don’t Go

“God in heaven,” I heard myself say, just as the sirens started.

I would tell you that men in blue took statements from Jackson and me before sequestering us, so investigators could grill us, riveting into our minds what had transpired that night. I would tell you if that’s what happened. But it didn’t go down that way.

It was Jackson pulled me out of my stupor and led me outdoors. We passed men in white and men in blue rushing in. I looked back one last time and saw Abel looking around like someone crazed, like someone had just dropped him from a starship and he was falling fast in space.

“Jesus, Jesus, Jesus, what happened?” I said, and Jackson kept repeating, “It’s all right. It will be okay.” We stood there in the darkness that felt suddenly frigid, Jackson with his arm around me.

A little while later, I think I said, “He will never let them catch him alive. Never.”

“I know that,” said Jackson. Then, “It’s nice out, but you can’t see no stars. Come on now, I’ll buy you a drink. I could use one.”

I took my apron off then, depositing it in the trash bin next to Jackson’s like there was nothing else to do, like it was the last thing we would ever have to do, and followed him to his old Lincoln.

__________

Arya F. Jenkins is a poet and writer whose work has appeared in numerous literary and online journals such as Agave Magazine, Brilliant Corners, Cleaver Magazine, and The Feminist Wire. Most recently, her poetry was nominated for a Pushcart award by the editors of Agave Magazine. Her poetry and essays have been included in three anthologies. Her poetry chapbook, JEWEL FIRE, was published by AllBook Books. Poetry is forthcoming in Blue Heron. Her blogs are http://writersnreaders.blogspot.com and http://beboptimes.blogspot.com.

A fast read like the food being cooked! Fantastic writing. Surprise and shocking ending!

A fast read like the food being cooked! Fantastic writing. Surprise and shocking ending!

Great descriptive writing! I swear I’ve been to this place and know these people.

Great descriptive writing! I swear I’ve been to this place and know these people.