Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

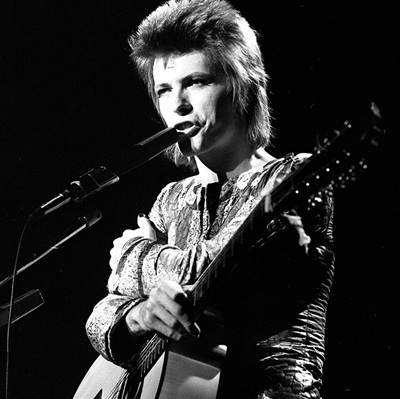

The first meeting of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn

_____

Excerpted from

Lush Life : A Biography of Billy Strayhorn

by

David Hajdu

______________________

Shortly after midnight on December 1, 1938, George Greenlee nodded and back-patted his way through the ground-floor Rumpus Room of Crawford Grill One (running from Townsend Street to Fullerton Avenue on Wylie Avenue, the place was nearly a block long) and headed up the stairs at the center of the club. He passed the second floor, which was the main floor, where bands played on a revolving stage facing an elongated glass-topped bar and Ray Wood, now a hustling photographer, offered to take pictures of the patrons for fifty cents. Greenlee hit the third floor, the Club Crawford (insiders only), and spotted his uncle with Duke Ellington, who was engaged to begin a week-long run at the Stanley Theatre the following day. “As soon as my uncle introduced us,” said Greenlee, “I turned to Duke and I said, ‘Duke, a good friend of mine has written some songs, and we’d like for you to hear them.’ I lied, but I trusted David. I knew Duke couldn’t say no with my uncle standing there. So, Duke said, ‘Well, why don’t you come backstage tomorrow, after the first show?’ It was all set.”

The next morning, Greenlee arranged (through Perelman) to meet Strayhorn for the first time in front of the Stanley Theatre before the 1:00 p.m. opening matinee. The day was chilly but still, and a light snow fell on and off. Strayhorn was collected, Greenlee would recall, and looked properly ascetic – “He was wearing his Sunday best, but they were pretty well worn.” They watched the first show, a long set of Ellington Orchestra numbers peppered with a tap-dance act (Flash and Dash) and a comedy team (the Two Zephyrs), then found their way through the baroque old Stanley, eight stories high, with thirty-five hundred seats and three full floors of dressing rooms. Ellington’s dressing room was the size of a large dining room and, in fact, was set up like one: several place settings were arranged on a table, and there was an upright piano along one wall. Ellington, alone with his valet, lay on a reclining chair in an embroidered robe, getting his hair conked, eyes closed.

“I introduced Billy, and we stood there,” said Greenlee. “Duke didn’t get up. He didn’t even open his eyes. He just said, ‘Sit down at the piano, and let me hear what you can do.'” Strayhorn lowered himself onto the bench with calibrated grace and turned toward Ellington, who was lying still. “Mr. Ellington, this is the way you played this number in the show,” Strayhorn announced and began to perform his host’s melancholy ballad “Sophisticated Lady,” one of a few Ellington tunes Strayhorn knew from his days with the Mad Hatters; as a trio, the group used to play a version inspired by Art Tatum’s arabesque 1933 recording. “The amazing thing was,” explained Greenlee, “Billy played it exactly like Duke had just played it on stage. He copied him to perfection.” Ellington stayed silent and prone, though his hair work was over. “Now, this is the way I would play it,” continued Strayhorn. Changing keys and upping the tempo slightly, he shifted into an adaptation Greenlee described as “pretty, hip-sounding and further and further ‘out there’ as he went on.”

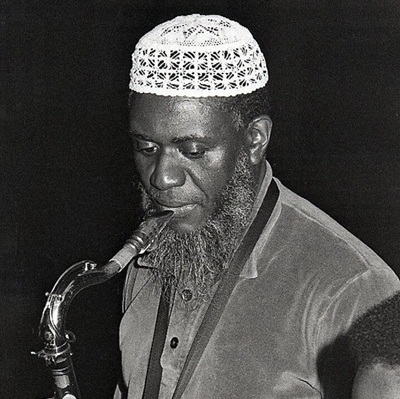

At the end of the number, Strayhorn turned to Ellington, now standing right behind him, glaring at the keyboard over his shoulders. “Go get Harry,” Ellington ordered his valet. (Harry Carney, Ellington’s closest intimate among the members of his entourage in this period, had played baritone saxophone for the orchestra since 1926, when he was sixteen years old, and the two frequently traveled together to engagements.) “Wellll ” proceeded Ellington dramatically as he faced Strayhorn eye to eye for the first time, Ellington gazing down, Strayhorn peering up. “Can you do that again?” “Yes,” Strayhorn replied matter-of-factly, and began Ellington’s ruminative “Solitude,” once more emulating the composer’s piano style. When Harry Carney entered the room, Ellington stage-whispered, “Listen to this kid play.” Again Strayhorn declared, “This is the way I would play it,” and reharmonized the Ellington song as a personal showcase. Brazenly (or naively) the twenty-three-year-old artist demonstrated both a crafty facility with is renowned elder’s idiom and a spirited capacity to expand it through his own sensibility. The potency struck Ellington, Greenlee recounted: “Billy was playing. Duke stood there behind him beaming, and he put his hands on his shoulders, like he wanted to feel Billy playing his song,” Carney hustled out and returned with two more members of Ellington’s musical inner circle: alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, thirty-two, a premier Ellington soloist since he joined the band in 1928, and Ivie Anderson, thirty-three, who became Ellington’s first full-time vocalist in 1931.

As this group gathered around Strayhorn, “Things got hectic,” said Greenlee. “Duke fired off a million questions about Billy’s background and training and so forth. Billy kept playing from then on, mostly his own things – ‘Something to Live For,’ which he sang, and a few others” (including a piece so new he hadn’t given it a title yet). Recalling the occasion in later years, Ellington focused on that moment: “When Stray first came to see me in the Stanley Theatre, I asked him the name of a tune he’s played for me, and he just laughed. I caught that laugh. It was that laugh that first got me.” However impressed he may have been by Strayhorn’s musical skills, Ellington was also struck by something visceral.

Uncertain how best to use him – Ellington’s orchestra already had a pianist – Ellington left Strayhorn with an initial assignment to write lyrics to an instrumental piece. As Strayhorn recalled, “I know how something-or-other it must have been to meet a young man in a town like Pittsburgh. I played for him. I played and sang. Uh, he, uh, he was – he liked me very much, and he said, ‘Well, you come back tomorrow,’ and he gave me an assignment. He had an idea for a lyric. He said, ‘You go home and write a lyric for this,’ and I did. I rushed home and I wrote this lyric.” (The title of the song and the lyrics are unknown.) Strayhorn returned to see Ellington the following evening and submitted his work but found that the frantic events of late had taken a visible toll on him. “Everybody was just so wonderful to me – Ivie Anderson particularly, because she was worried,” he said. “She said, ‘Lookit, you go out and get yourself a sandwich or something, because you’re not eating.’ I must have looked a little peaked.” Invited back, he visited Ellington again at the Stanley three days later, when he was given a second assignment, this time to apply his evident skill at harmonization to a vocal selection for Ivie Anderson. As Robert Conaway remembered, “After the meeting, he said, ‘He likes my work, and he gave me an assignment to do'”

The next evening, Strayhorn worked on his orchestration for Ellington, polishing it with the help of his friend Bill Esch rather than returning to the Stanley; Ellington left the theater early that night anyway and spent the after-show hours at the Loendi, a black social club in a rambling three-story brick house on the Hill. By the follwing evening, Ellington’s last at the Stanley, Strayhorn was ready and returned with his work, and, sharing his good fortune, he brought along Esch. Ellington, who was between shows, wrapped up dinner in his dressing room with Thelma Spangler, a striking, soft-spoken young woman he had met the previous evening at the Loendi. The three musicians huddled together on their feet, poring over music paper for about five minutes, discussing aspects of the arrangement animatedly, Spangler recalled. A chime sounded and Ellington tucked the manuscript under his arm, pronouncing, “Time to go back on.”

Spangler watched the show from the wings. Strayhorn and Esch stood behind the curtain, near Ellington’s piano, while Ellington passed parts of Strayhorn’s arrangement to the musicians on stage. “Duke gave some of the guys some tips,” said Spangler. “Like, he’d hum something to one guy, or he’d say, ‘You come in here.’ A couple of times he asked Billy something, and Billy answered him, and then Duke explained it to the band. It all happened very quickly. Then Ivie came out on stage. Duke whispered to her and raised his hand, and they did the song, just like that.” The arrangement was a slow-tempo version of “Two Sleepy People.” “Oh God, it was pretty, like something in a dream,” Spangler said. “Ellington smiled all over himself, and he told Billy after the show how happy he was with his music.”

Clearly pleased, Ellington offered Strayhorn work. The kind of work, however, remained unclear. As Strayhorn recounted, “He said, ‘Well, I would like to have you in my organization. I have to find some way of injecting you into it. I have to find out how I do this, after I go to New York.’ He was on his way back east then. So I said, ‘Well, all right.’ Ellington paid Strayhorn twenty dollars for his orchestration of “Two Sleepy People” and jotted down subway directions to his apartment on Edgecombe Avenue in Harlem. “They were packing up – Willy Manning was getting clothes together in trunks and everything,” Strayhorn recalled. “And off they went, and off I went back home and back to the drugstore.”

_________________

Lush Life : A Biography of Billy Strayhorn

by

David Hajdu

Excerpt from “Overture to a Jam Session” from LUSH LIFE by David Hadju. Copyright © 1996 by David Hajdu. Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

CAUTION: Users are warned that this work is protected under copyright laws and downloading is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

What a great excerpt! Thank you for sharing it; I am putting together a book

of Duke Ellington songs for beginning Jazz pianists and this was so helpful

and inspiring. I may frame the whole book around the collaboration of Duke

and Billy.

What a great excerpt! Thank you for sharing it; I am putting together a book

of Duke Ellington songs for beginning Jazz pianists and this was so helpful

and inspiring. I may frame the whole book around the collaboration of Duke

and Billy.