Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

*

When Cab Calloway and Dizzy Gillespie Fought Over a Thrown Spitball

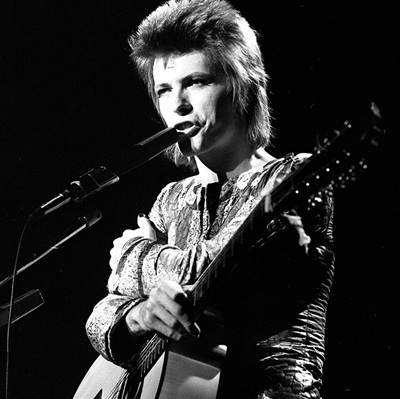

Photo Copyright by the Milton J. Hinton Photographic Collection

Dizzy Gillespie, the Palace Theater, Cleveland, 1939

______________

Excerpted from

Playing the Changes: Milt Hinton’s Life in Stories and Photographs

by

Milt Hinton, David G. Berger, and Holly Maxson

_________________________

In 1939, Doc Cheatham, who’d been with Cab for years, was feeling ill and decided to give notice. By this time, when it came to finding replacements, Cab would go to Chu [Berry] first. He knew everybody and was really on top of the music scene. Chu spent about a week looking around and then recommended a young kid named John Birks Gillespie, who everyone called Dizzy. Cab hired him.

We were at the Cotton Club when Diz joined us. He’d been playing with Teddy Hill’s band and really had no reputation to speak of. Even back in those days, he was hanging out with Lorraine, who was in the chorus at the Apollo and later became his wife.

At first Diz didn’t have a dime, so some of us helped him out whenever it was necessary. I remember giving him five bucks about a week after he joined the band so he could have his mouthpiece pleated. It was so worn it was ruining his chops.

Diz’s music was revolutionary. Even back then he was playing way ahead of the times. But only a couple of us who had our ears open listened. I knew he’d take music to a new place. So did Chu, Cozy [Cole], and a couple of the others.

Diz’s biggest musical problem was that he’d try playing thinigs he couldn’t technically handle. I’d often hear him start a solo he just couldn’t finish. Whenever that happened, some of the older guys would look over at him and make ugly faces. Cab usually showed the same kind of disgust and often scolded Diz at rehearsals or after a performance. He’s say things like, “Why in hell can’t you play like everybody else? Why d’ya make all those mistakes and have all those funny sounds come outta your horn? Play it like the other guys do!”

Diz would sit quietly, with his head hung down. He looked like a little school kid being scolded by the teacher.

When the weather was warm and we were playing the Cotton Club, Diz and I would try to get up to the roof between shows to work on our music. He’d take his horn and I’d somehow squeeze my bass through the narrow back passageways. Playing up there is how he and I became dear friends.

By this time, the Cab Jivers was going strong and I had a featured spot in the stage production. As one of the members, that meant I’d have a solo in every show. So during many of the intermissions when Diz and I would head for the roof, he’d help me with my solo for an upcoming performance.

He always wanted to change my way of walking chords, which was straight down the middle. Since I knew the tunes I’d be soloing on, he’d take them apart harmonically and give me flatted chords and very modern substitutions to use. Whenever I had trouble understanding, he’d demonstrate by playing the bass line on his horn, note for note.

The Cab Jivers always performed out in front of the band, and Diz would watch closely from his seat in the trumpet section toward the back of the stage. Each time I finished my solo, I’d turn around to get his reaction. If I had done well, he’d nod his head up and down or use two fingers to give me an ok sign. But if I’d screwed up, he’d make an ugly face.

One day, all of this came to a sudden end, and it was really due to the communication system we’d been using on stage.

It was summer and the band had gone up to do three Sunday shows at the State Theater in Hartford. A couple of days earlier at the Cotton Club, Diz and I had worked out a solo for me to play with the Cab Jivers on “Girl of My Dreams.” I’d also practiced it with him backstage right before the first show.

When it came time for the Cab Jivers’ feature, the four of us walked down to the front of the stage from our regular places on the bandstand. Then the back of the stage where the rest of the band was sitting was darkened, and a couple of spotlights were put on us.

We played a few tunes, but by the time we played “Girl of My Dreams” I’d forgotten everything Diz had showed me. I must have missed my solo by a mile. The tune ended and I turned around to get a reaction from Diz, who was sitting in the dark. He was holding his nose with one hand and waving at me with the other. It was clear what he was telling me – “You stink.”

At the exact same moment, one of the guys up on the bandstand thumped a spitball and it landed right in the spotlight next to where Chu was standing.

Cab was watching the show from the wings. He saw Diz’s gesture and he saw the wad of paper land. He never saw who threw it, but in Cab’s eyes, Diz was always wrong, so he didn’t have to study the situation any further.

When the show ended, most of the guys went back to the dressing rooms. The only ones left on stage were Benny Payne and Chu, who were talking off in a corner, and I was there packing up my bass. Cab must have stopped Diz in the wings at the end of the show because I could hear him yelling, “Well, you did it again! Those men were out there entertaining all those people and you’re sittin’ back there throwin’ spitballs just like you’re in school. What’s wrong with you? Can’t you do anything right?”

I couldn’t see Diz but I knew he wasn’t hanging his head. This time he was right. He always called Cab “Fess,” and I could hear him saying over and over, “Fess, I didn’t do it.”

The two of them went at it for a while. It got louder and nastier. A minute or two later I decided to walk over to the wings where they were standing, just in case. When I stepped around the curtain I saw two ladies standing a couple of feet from Cab, who was still wearing his white stage outfit.

Cab was yelling, “You did it! I was looking right at you when you threw it!” But Diz wouldn’t let it go. He was right and he had to prove his point. He moved closer to Cab and told him in a sharper tone, “You’re just a damn liar for saying I did it.”

Cab wasn’t going to let one of his musicians call him a liar, especially in front of those two fine-looking women. So he called Diz some more names and then threatened, “Now go on, get outta here before I slap you around.”

That made it worse. Diz stood there, arms folded, looking like the Rock of Gibraltar, repeating, “You ain’t gonna do nothin’.”

Physically, Cab was a big man. He’d learned how to street fight growing up in Baltimore and he was fast. Suddenly his hand was in the air and he slapped Diz across the side of his face. A split second later, Diz had his Case knife out and was going for Cab. I was just a couple of feet away, so when Diz took a swing at Cab’s stomach with his knife, I hit his hand and made him miss. Then Cab grabbed Diz around the wrist and tried to wrestle the knife away. Within seconds the big guys, Chu and Benny, had made it to where we were and quickly pulled them apart. Chu took Cab to his dressing room and Benny took Diz to the band room.

About ten minues later Cab came down to the band room, where we were all talking to Diz, trying to calm him down. Cab was still wearing his white suit, but one pant leg was covered with blood and he had a bandage around his wrist. He looked at Diz and told him, “Pack your horn and get outta here.” Then he turned and left.

Before we knew it, Diz had gone out the stage door.

The cuts on Cab’s thigh and wrist weren’t very serious. In fact, he did the second and third shows without any problems. Afterward, we took the bus back to New York and Cab rode with us. The trip was quiet, like when someone dies and no one really knows what to say.

Whenever Cab rode the bus, he had the first seat, directly behind the driver. It was about two in the morning when we pulled up to the Theresa Hotel, which was our usual drop-off place. Cab was the first one off. And when he stepped down, there were Diz and Lorraine waiting to greet him. Diz looked at him and said, “Fess, I’m sorry.” But Cab didn’t say a word. He reached out and touched Diz’s palm and kept walking.

About thirty years ago, I played at a reunion concert at Carnegie Hall for all the guys who’d worked for Cab over the years. Tyree, Cozy, Illinois Jacquet, Dizzy – just about everyone who was still living showed up. In the middle of the concert, before Dizzy was bout to do a solo, he walked over to where I was standing onstage and said, “Listen, as soon as I finish my solo on the next tune, you go into a vamp and I’ll grab the mike and start talking.” Tyree, who was standing next to me, seemed to know what Dizzy was planning. “Man, don’t get this whole thing started again. It’s been dead and buried for year,” he told Dizzy.

“Hey, it’s gonna be beautiful. Don’t worry,” Diz said, and he turned and walked to the center of the stage.

When Dizzy finished his solo, I started the vamp, and Cozy followed immediately. Dizzy grabbed the mike and scatted for a minute or two. Then he signalled us to stop playing, turned around to the band, and asked loudly, “Who threw the spitball?” Evidently, he’d told everyone but me what to do, because they all got and answered in unison, “Not me!”

I guess enough of the audience knew the story, because the place went wild. Cab came out front, took the mike, and said, “Diz, I know you didn’t do it.” The two of them embraced and the show went on.

That was the first time I ever heard Cab admit he knew it wasn’t Dizzy. In fact, in his book which came out a few years after the reunion, he says I was the one who threw it. Mel Torme, who reviewed the book in the New York Times, said some pretty negative things about me for not admitting my guilt and for letting Dizzy take the rap. I was very upset about it and when I saw Mel in Nice four or five years later, I told him how I couldn’t have thrown the spitball into the spotlight because I was standing in the same spotlight myself.

In his book, Diz was the first to publicly identify the true culprit. Of course, he’d always known, because the guy who did it was sitting with him in the trumpet section – Jonah Jones.

_________________________

Playing the Changes: Milt Hinton’s Life in Stories and Photographs, by Milt Hinton, David G. Berger, and Holly Maxson, published by

__________

Excerpted from Playing the Changes: Milt Hinton’s Life in Stories and Photographs, by Milt Hinton, David G. Berger, and Holly Maxson, published by Vanderbilt University Press. Copyright (c) 2008 by Milton J. Hinton Photographic Collection. All rights reserved.

Really enjoyed this story featuring so many legends.. especially like that in the end peace and love prevailed.

We could all use more of that these days.

Thank you so much for sharing it. ❤️