photo by Herman Leonard

Gary Giddins,

author of

and

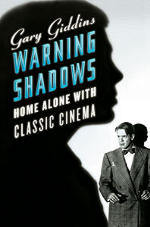

Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema

Gary Giddins was a long-time columnist for the Village Voice and a preeminent jazz critic who received the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award, and the Bell Atlantic Award for Visions of Jazz: The First Century in 1998. His other books include Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams: The Early Years, 1903–1940, which won the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award and the ARSC Award for Excellence in Historical Sound Research; Weatherbird: Jazz at the Dawn of Its Second Century; Faces in the Crowd; Natural Selection; Jazz; Warning Shadows; and biographies of Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker. He has won an unparalleled six ASCAP–Deems Taylor Awards, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Peabody Award in Broadcasting.

Giddins has been a frequent contributor to Jerry Jazz Musician. This is the 15th interview in our “Conversations with Gary Giddins” series.

He joins us in a June 1, 2010 discussion about his two new books.

_______________________

About Jazz

The story of jazz for the general reader as it has never been told before, from the inside out: a comprehensive, eloquent, scrupulously researched page-turner.

In this vivid history of jazz, a respected critic and a leading scholar capture the excitement of America’s unique music with intellectual bite, unprecedented insight, and the passion of unabashed fans. They explain what jazz is, where it came from, and who created it and why, all within the broader context of American life and culture. Emphasizing its African American roots, Jazz traces the history of the music over the last hundred years. From ragtime and blues to the international craze for swing, from the heated protests of the avant-garde to the radical diversity of today’s artists, Jazz describes the travails and triumphs of musical innovators struggling for work, respect, and cultural acceptance set against the backdrop of American history, commerce, and politics. With vibrant photographs by legendary jazz chronicler Herman Leonard, Jazz is also an arresting visual history of a century of music.#

*

About Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema

A brilliantly insightful and witty examination of beloved and little-known films, directors, and stars by one of America’s most esteemed critics.

In his illuminating new work, Gary Giddins explores the evolution of film, from the first moving pictures and peepshows to the digital era of DVDs and online video-streaming. New technologies have changed our experience of cinema forever; we have peeled away from the crowded theater to be home alone with classic cinema. Recounting the technological developments that films have undergone, Warning Shadows travels through time and across genres to explore the impact of the industry’s most famous classics and forgotten gems. Essays such as “Houdini Escapes! From the Vaults! Of the Past!,” “Edward G. Robinson, See,” and “Prestige and Pretension (Pride and Prejudice)” capture the wit and magic of classic cinema. Each chapter—ranging from the horror films of Hitchcock to the fantastical frames of Disney—provides readers with engaging analyses of influential films and the directors and actors who made them possible.#

_____

“A historian has many duties. Allow me to remind you of two which are important. The first is not to slander; the second is not to bore.”

– Voltaire

___________________

JJM In the introduction to Jazz, you and co-author Scott DeVeaux wrote, “…the dust of history has by no means settled on jazz. The canon of masterpieces, far from fixed, remains open to interpretation, adjustment, and expansion.” How does this book differ from other jazz histories?

GG We had a few goals that would specifically distinguish it not just from other histories, but also against certain positions that had been widely taken and with which both of us disagreed. First, we were tired of the kind of jazz chronicle that separates jazz from the rest of the world, as though jazz has been in a vacuum, and just a series of begats, as in Louis Armstrong begat Roy Eldridge who begat Dizzy Gillespie who begat Miles Davis, as though nothing else was going on. We very much wanted to tie the major historical points of jazz to other historical issues.

As I have said many times, the big band era could only have taken place during the Depression, bebop is very much a part of the film noir era, cool jazz relates to a certain attitude of post war 1950’s California, hard bop is a response to urban life, the avant-garde era is very much a part of the civil rights era, and so on. At the same time, we wanted to create a couple of different narrative structures, one being the chronicle of jazz as it developed, but also – especially in the final chapters of the book – a narrative that suggests jazz has always been responsive to what was going in the pop and classical world, particularly the influence on jazz of rhythm and blues or blues or rock and roll or hip hop. Musicians who come into jazz grow up in the same world as everybody else. Tony Williams was one of the great jazz drummers of his day but he was part of a generation that was brought up on rock and was thus an obvious candidate to go into fusion. If you look today at Jason Moran today, one of the most sophisticated musicians we have, you will find that he uses hip hop rhythms, at times so subtly that maybe only a hip hop fan would even recognize them.

Musicians exist in the world, not just in the jazz world. The fact that Charlie Parker liked to play tunes associated with Broadway shows or pop singers, that he played “White Christmas” in a club in New York, or liked to run around singing a Mario Lanza hit, suggests a larger embrace of the musical culture of his time than simply grounding it in Kansas City and the influences of dominant jazz saxophonists like Hawk, Young, Berry, or Buster Smith. He spoke of Jimmy Dorsey, Stravinsky, and learned a great deal from analyzing film scores. One of Louis Armstrong’s key contributions was to say that jazz isn’t just about the New Orleans repertoire – he could play tin pan alley tunes and quote operatic arias. So we wanted to get away from an approach that put jazz into a vacuum.

| JJM The 78 listening guides are a fascinating part of the book…

GG Yes, and they are another important difference from any other trade book I have seen on jazz. We chose recordings that reflect many aspects of the music as it developed, and offer second-by-second breakdowns, calling attention to details that even experienced listeners may not have noticed. If you aren’t already an ardent jazz enthusiast, they will give you a sense of how much is going on in a three minute record. We wrote the guides mostly in non-musicological language so that non-musicologists like me can understand it – there is very little of “it goes from a G major to an F sharp minor.” We tried to avoid that. My own experience with the listening guides was that when Scott would send them over for me to read I would frequently hear things I hadn’t heard before. For example, I thought I knew Cecil Taylor’s “Bulbs” backwards and forwards, but I didn’t realize there were nine motifs in it. Or, the fact that Miles’ “ESP” is harmonically so complex that it is hard to figure out the nature of the chords are the key center. JJM These listening guides got me to listen to notable recordings completely differently, and I have to say that I have a renewed appreciation for them now. GG That was my response as well. I wrote the introductions to most of the guides, so at first I was working with basically things that I knew. But then I would study the LG’s and interpolate into them things I hadn’t been aware of. It is a fascinating way to listen to this music. JJM For these listening guides you feature pieces like Duke Ellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy,” “KoKo” by Charlie Parker, and, as you pointed out, “Bulbs” by Cecil Taylor. How did you and Scott decide on the pieces to have listening guides for? GG Believe it or not, it took us a year to nail down the four CD’s – we went back and forth, back and forth. I chose what I thought were representative recordings from various periods, Scott had favorites, and we started to integrate them. Sometimes I would mention a piece that he didn’t know, and vice versa. I sent him MP3 files and he would listen to them and then we would discuss the pros and cons. The decisions were not always entirely musical, because there was always a timing issue – all the tracks had to fit on four CD’s. Doing the math was a challenge, not unlike putting together a jigsaw puzzle, making it all fit. In a couple of instances we had to say the hell with this song because it’s too long or, in a few instances, we couldn’t get the rights. We had to have “So What,” which is like 10 or 11 minutes, but there were other tracks we wanted that were also that long that we had to leave out, so we found something shorter to represent the artist. Then, after we finally got our four discs fairly settled, Tom Laskey at Sony took care of leasing the rights, which were not always available. For example, we couldn’t get the rights to anything on Black Saint, which was undergoing an ownership transference, so at the last minute we had to scratch a few tracks and find substitutions. There were other things that were just bizarre. We had to let go of Lunceford’s “Annie Laurie,” because Universal claimed it did not own the anthology rights. I still don’t understand that. And I had to turn cartwheels to use an 80-second 1916 track by Wilbur Sweatman that the legal owner, EMI, didn’t know it owned. So it was a really complicated task, but it began with the idea that these were tracks we loved and that meant a lot to us, and were also indicative of the artists and periods we were discussing. I did most of the writing, but the one chapter I couldn’t do was the one on jazz-rock fusion, so Scott wrote that one and a few others. But even when I might be writing a chapter, I would be working from outlines he put together from his 25 years of teaching at the University of Virginia, and there were certain important Power Point ideas that had to be included. So this became a true collaboration where we worked with each other’s ideas, no matter who wrote a particular page. I suspect there isn’t a page in the book where both of our presences aren’t felt. For me, it showed how two minds can be better than one, as I was looking at several ideas that were novel to me. I spoke at a conference when the textbook version of the book came out, and I said that collaboration basically gives you permission to plagiarize, because anything Scott came up with, I could use, and anything I came up with, Scott could use. He would be working on the swing chapter and I would say, you know, I wrote about that guy in Visions of Jazz, and he would say, yes, I know, I read it. So I reminded him that anything in there he could use – that this is a collaboration. Anything I have done is yours and anything you’ve done is mine. That was a very empowering feeling. It helped to wean me off of reading other text books, which I often found terribly depressing. If the other textbook was awful, I’d think, man, we have a lot of nonsense to make up for; if it was good, I’d think how can I possibly improve on that? Finally, during one of our weekly phone calls, Maribeth and Scott said put the other damned books away, we called you for what you know, and that’s the way it was.

JJM When I was reading your book I couldn’t help but equate it to Ken Burns’ film – now a decade old – in terms of the importance of presenting, in your case, a written history of jazz. One of things I remember about Burns’ film is the criticism he got from people who felt he didn’t profile certain artists, whether it was Bill Evans, Stan Kenton, or whoever the critics favored. You must have been cognizant of that since you were such an important part of that film… GG There are two kinds of critics; those who review the book you wrote, and those who review the book you didn’t write, and I don’t take the latter seriously. If they point out that somebody might have been included, and it is someone I hadn’t thought of, I may think, “Damn, I didn’t even think of that.” But the ultimate thing is you are writing about a subject as you see it. You make choices every step of the way. If you think that we left out somebody of great consequence, you write about him or her. There are people we left out that I adore. I hate the fact that Jaki Byard and Booker Ervin and Jimmy Heath and Sonny Clark and others don’t get as much attention as I’d like to have given them, and anyone who knows anything about my work knows how painful it is to me that there is no Louis Armstrong after 1928. But the fact is that there are more Armstrong records than anyone else in the four CD’s – I think there are six tracks with him on them – and it just didn’t fit into the narrative or the space allotted to us on the four discs to also put in a 1938 or 1955 track by him. We didn’t have 2000 pages to work with, we didn’t have unlimited access, we had to carve out a narrative representative of the story we wanted to tell. If the book is effective, then readers won’t stop with it. They’ll discover that Charlie Parker is interesting and get some Charlie Parker recordings, and in the process discover the pianist Al Haig, who we don’t talk about, and maybe discover the incredible records Stan Getz made at Storyville with Haig and Jimmy Raney and Tiny Kahn in the early 1950’s. But, while we don’t talk about everybody, you can find people on your own. That’s the way these things are supposed to work.

GG If he or I felt strongly about Stan Kenton, then Kenton would be in the book. Scott and I never had arguments that went unresolved, and I don’t remember a serious argument in the six years we worked together. We had some disagreements. There are some tracks in the book that I would not have used – some of the fusion tracks important to him were not on my list – but I listened to them and realized that they were valid and should be included. Initially, Scott questioned me about why I included Artie Shaw. I sent him an MP3 and he instantly got why. Both of us have written other books. I have a chapter on Stan Kenton in Visions of Jazz that is a partly satirical look at him. Kenton has his following, and maybe I am wrong about him, but I am not pretending to be all things to all of jazz – I can just write from the perspective that I have as a guy who has been listening for more than 45 years, and writing for almost 40 years. I bring to it what I bring to it, but it is not the last word. If someone wants to say that jazz critics have been underestimating Stan Kenton and writes an essay to prove that point, great! I’ll be the first to read it. I love finding out I was wrong about something; it proves to me I’m still breathing. There’s a piece in Natural Selection about how I initially attacked Miles Davis’s Agharta, which later became a favorite recording of mine. This summer, at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Ashley Kahn conducted a panel on Bitches Brew and a new book by two Italian critics about the making of that record. I was in the audience, and near the end a moderator, Enzo Capua, one of the key forces behind Umbria, asked me to tell the Agharta story. Better late than never! Somebody asked me recently what were the things that influenced me when I started writing, and I said that when I was growing up, there were a lot of musicians who were routinely attacked in Downbeat. There were three saxophonists in particular who I loved – I started listening to them before I read about jazz – but when I started looking at the magazines, they were always getting dissed: Paul Gonsalves of the Ellington band, Charlie Rouse in Monk’s group, George Coleman, who preceded Wayne Shorter in Miles’ band. In each case they were attacked because they weren’t the guy they replaced. In other words, Gonsalves was no Ben Webster, and Rouse and Coleman were not John Coltrane. That’s one reason I started writing because I thought those critics were nuts. If you can’t hear how distinctive Rouse is, that’s your problem, not his. So, I am all for that kind of response. On the other hand, I have to say, I don’t think anyone owes Amazon or any of these websites any favors for unleashing amateur critics. Some idiot will write, “Moby Dick is a bore. I hate Moby Dick.” Who cares about these people? The guy who made the Kenton remark obviously didn’t read the book. I don’t care where you’re coming from, if you read the book, you can say we left out people, but there are 700 pages of stuff, and you are telling me there is nothing in that book that you found valuable? I don’t buy it.

JJM In addition to dedicating your book to your assistant Elora Charles, you dedicate it, in memoriam, to over 30 New York movie theaters that are no longer open, among them The Carnegie Hall Cinema, the New Yorker Theater, the Saint Mark Cinema, and the Regency Theater. Concerning their demise, you wrote, “Nothing in the long history of America’s long disregard for architectural style is more disheartening than the wanton destruction of these magnificent tributes to art and monopoly.” What have we lost as a society as a result of people staying home to watch film as opposed to going out to these theaters? GG The theater is a public venue, so you went out and became part of a crowd with strangers. Usually you went with a friend or spouse or family, and though you may not have had much interaction with anyone else, there is always a little interaction – laughing or crying in tandem, and especially in that moment, when the lights go up, and if it was a really great film, you exchange smiles or other signs of mutual recognition. When you are sitting in the theater, in the dark, if the film is really doing its work, you are part of a group. There is nothing quite like several hundred people laughing together, all participating in the same joke, or all silently weeping, all sitting on the edge of their seats. You can’t replicate that at home alone. Comedy seems to suffer the most because if you are watching a good tear jerker alone you might tear up, but laughter often requires company. You might chuckle, you might smile, but it is much harder to give up loud guffaws in private. A couple of years ago, I saw Going My Way in a packed theater for the first time, a film I figured I knew up and down, and which has some very amusing moments. Yet not until that screening at Lincoln Center did I realize how effective it is as a comedy; the laughter began as soon as Bing appears as a priest in a straw hat chasing a ball under a truck and getting sprayed by a street cleaner – an old Mack Sennett kind of physical humor. From that point on, for all the dramatic scenes, the laughter was almost constant.

_______________________________________ “Nothing in the history of America’s long disregard for its schizophrenic architectural style is more disheartening than the wanton destruction of these magnificent tributes to art and monopoly.” – Gary Giddins _____ A sampling of New York-area theaters Giddins honors “in memoriam”

_______________________________________ Five short excerpts from Warning Shadows – From “Houdini Escapes! From the Vaults! Of the Past!” For nearly five years, beginning in 1918, Harry Houdini – the most famous magician since Merlin, most fabled escapologist since Jonah, most resourceful publicist since Barnum – tried his hand at filmmaking. He starred in one fifteen-chapter, five-hour serial and four feature-length films (a rumored fifth feature, The Soul of Bronze, probably was not made and almost certainly wasn’t distributed), at times involving himself as the producer, writer, and director. Houdini displayed little cinematic aptitude, yet the viewer who plunges, handcuffed or not, into Kino’s three-disc DVD tribute, Houdini the Movie Star, may surface with the showman’s grim, stocky, square-faced, curly-haired, gimlet-eyed glare forever locked in memory, like an unshakable specter from the past. Houdini was no actor, but he had presence. At times, he resembles a more muscular, Hungarian-looking cousin to the mute magician-comedian Teller. With this set, Houdini’s real-life flirtation with spiritualism is rewarded after all: the legendary illusionist retakes his corporeal self on celluloid – once again, bound for glory. – From “It Wasn’t Beauty Killed the Beast” King Kong/Grass/Chang The miracle of King Kong is that it has survived three-quarters of a century so well. A childlike if never quite childish myth that has printed indelible images in the mind and on the culture, the film continues to elicit an emotional involvement when all we expect is to rekindle a childhood frisson. Why do we care about this giant ape, this animated puppet with monstrous nostrils and googly eyes? Why do we read so much into a transparently simple monkey-out-of-jungle fable, feeding on unstated fears of imperialism, racism, sexual repression, rape, wanton violence, civilization’s discontents, Darwinian mazes, and any other theme you care to throw into the mix, with the possible exception of all that final-curtain nonsense about beauty and the beast? It wasn’t beauty killed the beast. It was Denham (played by Robert Armstrong as an alter ego for the film’s producer, Merian C. Cooper) and his gas bombs and the kidnapping of Kong – “We’re millionaires, boys, I’ll share it with all of you,” he says. – From “The Orson Welles Dilemma” What is it about Orson Welles that drives his chroniclers around the bend? Each emerges from the great man’s messy life and messier legacy convinced that he or she has found the explanatory Rosebud. The mystery they fell obliged to explain is not how he survived as an independent filmmaker, creating remarkable films that were not mutilated by producers; but rather why the erstwhile genius of radio, theater, and movies, friend to presidents, and civil rights champion ended up as an obese television pitchman for cheap wine. Welles’s chroniclers are either boosters or detractors, and they mingle like the sharks in The Lady from Shanghai, devouring each other. The reputation of his onetime colleague John Houseman as a mighty, often courageous producer turned professional elitist and financial investment shill has been additionally muddied by his turn as an unreliable memoirist with an ax planted in Welles’s skull. Pauline Kael’s “Raising Kane,” which conclude that Citizen Kane was really the work of its co-scenarist, Herman Mankiewicz, cashiered any respect she might have earned as a scholar, not because she got so many facts wrong but because she refused to correct or acknowledge them. In his psychological broadside Rosebud, David Thomson expressed the hope that Welles’s Don Quixote not be release because, given its “tattered” legend, “actual screening would be so deflating.” The British critic Clinton Heylin has written a defense of Welles, Despite the System, that is so violently ill-mannered as to render his good research indigestible. – From “A Rosetta Stone for the 1950s” Ben-Hur/The Man Who Fell to Earth/Bad Timing William Wyler’s Ben Hur (1959) and Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) are oddly companionable. Both are based on novels that track the travails of fish out of water, strangers in strange lands, messiahs, aliens treated badly by the natives but triumphant in the long run. Both are protracted, self-important, and fatiguing, yet remain in their best moments visually and aurally sumptuous. These films now have something else in common: they are redeemed as exemplary DVDs, which fail to make them better movies but do amplify their finer points. This isn’t just a matter of the tails – documentaries, interviews, commentaries – wagging the dogs, which have never been more brightly spruced. DVDs encourage and demand skill at fast-forwarding; they prompt you to watch episodic films episodically. Watching Ben Hur all at once is like sitting down to a ten-course meal and finding that every course consists of potato dumplings except for the seventh, which is strawberry shortcake. That would be the chariot race. Segmented viewings of The Man Who Fell to Earth counter its stubborn lack of dramatic thrust. The profuse extras reconstruct the deconstructed films so that the viewer, who may once have dismissed them as kitsch, can now participate in the business of creating kitsch. From “Dog Days” Lady and the Tramp/Hayao Miyazaki/Max and Dave Fleischer As every parent knows, most family entertainment is no such thing – it’s more often preschool entertainment, a much easier sale; or adolescent entertainment, which for boys tends to emphasize toilet jokes and special effects, and for girls sexual dilemmas with a Nancy Reagan punch line. Niche marketing, like global warming, is a slow, inviolable process, melting consensus and leaving the Beatles as the only bulwark against complete cultural disunity. Let’s blame Michael Eisner. You remember him: imperious CEO of the Disney empire, who chased Jeffrey Katzenberg from the magic kingdom; attempted to emulate Uncle Walt on television and rendered his base audience comatose; banned wine from Euro-Disney; outsourced animated features to Pixar; and went an extra step by declaring two-dimensional cartoons obsolete. My own theory consigns decline and fall to the release of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), based on two remarks by my then seven-year-old. As Frollow waxed insane before the fireplace, thinking of Esmeralda, my daughter asked, “Why is he so angry?” You try and explain. At the end, when Quasimodo – depicted as cute but pimply – united Esmeralda and Phoebus in marital harmony, she asked, “Is he their pet?”

_______________________________ This conversation took place on June 1, 2010 # Text from publisher. |

I had no idea there were so many books on jazz. I’ve read maybe six. I guess I’ve got a long way to go. And asto looking for old records. Many years ago, I had a 78 album of Wild Bill Davison playing trumpet with someone else playing a violin. Yesterday was the song they were playing; not the Beatles Yesterdays. It was the most gorgeous song and the album was put out by the old Gary Moore who was a jazz enthusiast. Sonny Terry played a dime store horn and it was great, too. Lots of greats on the album. I played it to death. They never made a remake, at least as far as I know. Now on to the movies and the trailers. We used to call them the previews. And all the ads at the movies now and the ads for the TV shows. All of it so loud and everything blowing up and exploding. I sure miss connections and all the great happenings that connections produced. Music, face to face conversations, books that were wonderful. Well, anyhow emails connect us and that’s a good things … I’ll go with that …