.

.

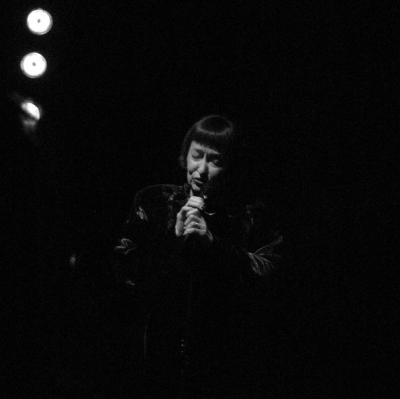

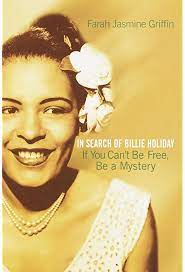

Farah Griffin, author of In Search of Billie Holiday: If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery

.

.

___

.

.

…..More than four decades after her death, Billie Holiday remains one of the most gifted artists of our time, and also one of the most elusive. Because of who she was and how she chose to live her life, Holiday has been the subject of both intense adoration and wildly distorted legends.

…..In an interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, Columbia University Professor Farah Griffin, author of In Search of Billie Holiday: If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery, helps sort out the life of Lady Day.

.

.

___

.

.

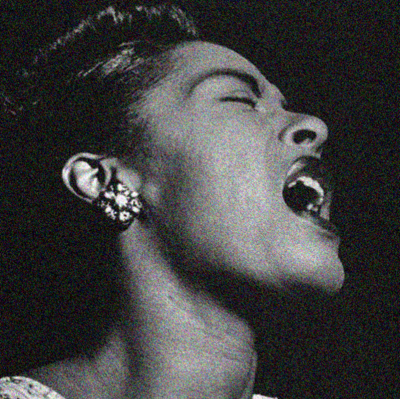

“The Meaning of the Blues,” by Christel Roelandt

Billie Holiday

.

.

___

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

FG It changed a lot. I don’t know if I had just one hero. My dad is probably my most consistent hero more so than any number of the more well known people who came in and out. So, I would have to say my father.

JJM You chose the final line of a Rita Dove poem called “Canary” for the title of your book, If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery. Why did you choose that?

FG First of all, I have always loved that poem. Initially the working title of the book was “Lady of The Day,” which is a play on her name, and also I thought that like “flavor of the day,” there are so many different Billie Holiday’s in circulation in our culture. I read the poem again after writing the first draft of the book, and I realized that it seemed to encompass everything I was coming up with in my research – that the real Billie Holiday, in spite of all these efforts to know her, remained a mystery. There was also this sense that she escaped a certain kind of freedom except in her own music.

JJM How d id your father’s death in 1972 inspire your interest in Billie Holiday?

FG My dad and I were very close. He was a jazz fanatic who introduced me to the music. When he died, I wanted to know as much as I could know about him. I imagined the things that he might have guided me to, so I listened to the music he loved. Because he frequently talked about Billie Holiday, and because the film Lady Sings the Blues came out at the same time my dad died, I started reading about her and listening to my dad’s Billie Holiday albums, while also asking my mother about her. So, I mark the beginnings of my interest in her with my father’s death.

JJM How did her music move you emotionally as a young woman?

FG I liked her music right away. It seemed to express a kind of sadness that I felt over the loss of my dad, and I kind of link them together in some ways. I was experiencing emotions that I couldn’t really articulate because I was too young to do so, and she seemed to articulate them for me. I couldn’t understand why I liked her voice, because it didn’t sound like any other voice that I considered to be a good voice. Aretha Franklin had a good voice, Sarah Vaughan’s was a good voice, but Holiday’s wasn’t, so I didn’t understand why I liked it but I knew that I did. I kept listening as much as I could and asking my mother and grandmother to get me more. Later on I discovered different versions of her. I discovered that she wasn’t always singing those sad songs, that sometimes she was funny or bubbly or hip, and that music could be all those things. So, it was a real process of discovery for me.

JJM Many of us have a one-dimensional image of Billie Holiday as living a life of pain and sadness. Was this image of Holiday more marketing than truth?

FG I don’t think it was. I think certainly after her death it was very much part of the marketing. I also think it was part of the truth – but only part of the truth. That is the thing that is most important to keep in mind, that the complexity of someone’s life isn’t defined only by those sad moments. I also don’t want to be overly optimistic and claim that her life wasn’t a life marked by sadness, because sadness was clearly part of it – but only a part. There was also joy and pleasure and all those things. Sadness wasn’t the only experience she had.

JJM Why do we as a culture seem to fixate on that aspect of her life?

FG I think there are some very complex reasons why we fixate on this non-complex version of her. One, I think that we have inherited a notion of the genius, tragic artist. The genius in turmoil, the sensitive and tragic artist, is a very romantic notion. It is part of a cultural inheritance. Two, an extension of that is the way we think of jazz musicians. We do grant them a sort of emotional complexity, and when you combine that complexity and sensitivity with a racist society that doesn’t appreciate the art the black musician produces, that feeds into this sadness aspect as well. Third, I think we are really invested in tragic women – in women who dare to be unconventional in any way have to meet a tragic end – it’s the price they have to pay. I think that is why Marilyn Monroe continues to fascinate us. I think all three of those strains are at work in the way we want to see Billie Holiday.

JJM The last song that she wrote is called “Left Alone,” which was never performed or recorded. Here is a stanza from the song:

Maybe fate has let him pass me by

Or perhaps we will meet before I die

Hearts will open, but until then,

I am left alone, all alone.

Did Billie Holiday look for personal salvation outside herself in her relationships with men?

FG From what we can tell, both from her own biographical statements and from people who knew her, I think that she probably did. But I would say that more so than looking for salvation in a man, she looked for it in her art form. Her continuing insistence, in spite of everything, to get up and try to perform everyday. Carmen McRae says she was at her happiest when she was singing, which suggests to me that the creation of her music was also a striving for a certain kind of salvation that we don’t talk about. It is easier to see it because she would use words like the song lyrics that suggest that she was looking for personal salvation in a man. In reality, I think she was also looking for it in her music.

JJM Why did John Hammond feel recording “Strange Fruit” was “artistically the worst thing” for Billie Holiday to do?

FG I think for a couple of reasons. One, he felt like it was the beginning of her switching from the kind of jazz she had become known for singing. Her popularity was built more or less on cabaret or “torch” songs. “Strange Fruit” generated an audience desire for a certain version of Billie Holiday that was very different from the one that Hammond would have cultivated – the one we would hear in those early recordings with Teddy Wilson and Benny Goodman. “Strange Fruit” is much more somber, and the political people on the left are going to take it up. It really just changes her persona and performance style, and that was detrimental to what he saw for her career path.

JJM Well, it becomes more artistic in a way…

FG Exactly, and more self-consciously so. That is what Hammond would have seen as very limiting.

JJM Two white men, Hammond and Milt Gabler, played critical roles in Billie Holiday’s early career. How did their visions for her differ?

FG Gabler is the one who recorded “Strange Fruit.” His vision for her was a little more multi-dimensional than what Hammond would have seen at first. I think Hammond was always looking for the next “thing.” So, there was Bessie Smith and then Billie Holiday was to be the next “thing.” Gabler, on the other hand, saw that there were a variety of artistic possibilities for Billie Holiday. So, he would record her doing popular torch songs at the same time that he would record her doing songs that would become jazz standards. He didn’t feel there was a one-dimensional way of presenting her material. She was ready to branch out, and Gabler was the ideal producer to hear what it was that she could do. That is the big difference between the two.

JJM Was her 1956 autiobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, a way for her to provide an alternative to the one-dimensional Billie Holiday of the popular press?

FG It is a really weird book. On one hand, it tries to present itself as trying to provide an alternative to what was appearing in the tabloids about her. On the other hand, I also think that they are writing a book with the intent to sell it. They know that a “tell all peek into my drug addiction, my downfall and my rise” is something that is going to sell. So, I think it would be wrong for us to look at that autobiography and think that it is the alternative story to what the tabloids were giving us. It was not any more real, it is just different.

JJM And she just needed the money, of course…

FG Right.

JJM So, there were a number of vehicles that were produced that were meant to combat this image. The autobiography was one. You also write about the 1972 film, Lady Sings the Blues. The great saxophonist Rahsaan Roland Kirk was quoted as saying, “She (Diana Ross), was fine when she was in the Supremes, but why did she have to go and ruin my Lady Day dreams?” What was the public’s reaction to Diana Ross being named as the actress to portray Billie Holiday in this film?

FG I think that for people who knew Billie Holiday – her fans who remembered her when she was alive – thought it was ridiculous that Diana Ross was going to play Billie Holiday for a number of reasons. Number one, she didn’t look at all like Billie Holiday and wasn’t going to be able to. Number two, she wasn’t considered a serious artist. She was a pop star, a Motown machine. She didn’t have the kind of emotional depth in her music that Billie Holiday had. She wasn’t a jazz vocalist or any of those things. People who had known Billie Holiday, those who had worked with her as well as her fans, were very upset and resentful. For another generation of people who knew nothing about Billie Holiday, Diana Ross would come to embody for them Billie Holiday’s life story. When they thought of Billie Holiday they would think of Diana Ross’ portrayal of her, and this would become more dominant in their minds than anything Billie Holiday ever did or sang. So, there were those kinds of conflicting responses to Diana Ross portraying her.

JJM Lana Turner and Ava Gardner were being considered to play the role of Billie Holiday?

FG Yes, initially in the late fifties, when a discussion of a movie on Billie Holiday first took place, they were being considered for the part. Although, if we don’t think about it in hindsight, but only think about it from that point in time, it would have been outrageous but not necessarily all that surprising. White actresses played black female characters often. In the film Pinky, there is a white actress who plays the lead character – a very fair skin black woman. Ava Gardner played Julie in the movie version of Showboat, a role Lena Horne thought she would have got. So, this was happening a lot, and it culminates in a discussion of Elizabeth Taylor playing Cleopatra, a role that Dorothy Dandridge wanted.

JJM What was the Ebony Magazine brand of image making, and how did Ebony portray Holiday’s public image?

FG In the book, I write about one particular Ebony story, and then there is another one published later that I couldn’t get permission to reproduce because it is a photographic essay. Ebony was born out of the great migration and the end of World War II, and was a magazine of the emerging black middle class. Ebony‘s favorite cover girl was Lena Horne, and Hazel Scott is also featured quite a bit. There were ongoing efforts made to represent black womanhood as elegant, middle class wives and mothers, as well as working wives and mothers. The first Billie Holiday story in Ebony was a 1949 cover story, after she gets out of prison. It is a “comeback tale.” It is sort of like the way People magazine does those stories now, after someone has done drugs and has gone through rehab. She talks of how she paid her dues, yet there are still people out there who want to hold her back. She talked of buying a house in suburban New Jersey, about wanting children, having a terrific wardrobe, etc. That’s the whole story. Later on, just before her autobiography was published in 1956, they do another story that is basically a photographic essay of different parts of the autobiography, especially the most lurid parts. For example, she is actually posed leaning on a lamp post, signifying her early days as a young prostitute, or in bed with her husband when the cops barge in. It is very sensational in a way we would expect to see in tabloids today, except these aren’t candid photos or paparazzi photos, these are photographs that have been posed for and staged. So, I see those as the two Ebony stories presenting two Billie Holidays.

JJM It was a way for her to kind of address these issues before a skeptical black audience.

FG Exactly, especially a middle class audience. Ebony at that time was in just about every black home, and it was a way for her to address this audience. Ebony was also a place where you could “come back” to the community. It does this sort of redemptive work on one’s public image. She could address that audience there.

JJM You wrote, “What angers me most is the authority granted the white men who controlled her life and in this instance seem to be in control of her memory as well.” Can you explain this?

FG That was especially in reference to a BBC documentary called “The Long Night of Lady Day.” It was a very informative documentary, and was the first thing following the film Lady Sings the Blues that tried to set the record straight. The problem in the documentary is that the people who were presented as the authorities of her life, and who made decisions about her life and interpreted its meaning were all white men. It doesn’t show how there would have been different power differentials in her relationships with those men – the story is more complex. It is a the complexity of their relationships to her that doesn’t really get voiced in that documentary. Therefore, they become the arbiters of her legacy that I thought was somewhat problematic.

JJM In essence, European intellectuals had a big role in this invention of her in a way.

FG Right, and again, I think it is a double-edged sword. What they brought to her was a level of complexity that the American popular media would not have done. She always recognized that European audiences, in general, viewed jazz musicians as serious artists. Certainly, European intellectuals granted her that status. There is an interpretation of black life as only being tragic under the circumstances of U.S. racism, so it doesn’t really see the resiliency of black life, and that was certainly the case in portrayals of Billie Holiday.

JJM When she sang “Strange Fruit” overseas it was interpreted here in America as a pretty strong indictment of American racism.

FG Right, and that is certainly the way the Europeans would have seen it as well, and I think that is what she meant by it. It is a critique of American racism, and it is a song that she is known for that she made popular. It is always easier for those intellectuals to see the race problem of the United States, but not really see it as an indictment of what is going on in Europe. Around this time they are all having problems with their colonies and the African Independence Movements, but American race relations don’t implicate them in the same way.

JJM Did the fact that she sang “Strange Fruit” in Europe make her more vulnerable to investigation? Did that make the FBI more interested in following her?

FG I haven’t found evidence that it opened her up (to more investigation). She did it at a time, though, when many black artists and intellectuals were making agreements not to be critical of the United States abroad. Those who didn’t make those agreements and who were considered more serious threats than Billie Holiday was – W.E.B. Debois and Paul Robeson – really suffered the consequences of not making that agreement so they couldn’t even get passports. Billie Holiday was already so followed and tracked down and harassed by federal agents and local police that it would have been hard for them to do anymore than they had already done. Although earlier in her career, what brings her to the attention of the FBI was not her narcotics use at all, it is her singing a song called “The Yanks Aren’t Coming,” which would have been a follow up to “Strange Fruit.” That is when they first take notice of her.

JJM Malcom X wrote of Billie Holiday, “Lady Day sang with the soul of Negroes from the centuries of sorrow and oppression. What a shame that proud, fine, black woman never lived where the true greatness of the black race was appreciated.” You then point out that cultural critic Albert Murray writes of Holiday and emphasizes her musicianship and artistic achievement, and her role in the black musical tradition. You write, “He relegates the tragedies in her life to “sensational publicity” and her choice of material, instead of racism, sexism or drug addiction.” How do black intellectuals differ in their view of Holiday?

FG You can find out a lot about the black intellectual debates concerning the meaning of black music, the meaning of the blues, and the meanings of jazz in terms of how they deal with Billie Holiday. So, someone like Albert Murray will say that the blues are not about all that sadness, poverty and racism – that in fact the blues are invented as a respite from those things and in spite of those things. The blues are a way of asserting humanity in the face of adversity. For him, Billie Holiday is in that blues tradition, especially the Billie Holiday that swings, and the Billie Holiday that sings with Count Basie. She is definitely in that “stomping the blues” tradition that is his thesis, but by paying attention to the tragic elements in her life, what we do is move away from the important contributions she made as an artist. On the other hand you have someone like Amiri Baraka who feels that black music is a barometer of black life in the United States, particularly the blues. For him, Billie Holiday comes to stand for black longing for freedom. He has written four or five pieces on her, and unlike Murray, I think that she is the quintessential blues person for him. Later on, black feminist intellectuals like Angela Davis looked at her in a different way – on the one hand torn about whether or not to hold her up as a kind of a foremother because she sings all those “my man done me wrong” songs, or on the other hand does she sing them in a way that offers a critique because she is already playfully deconstructing them? I think you can get to the heart of debates about black music by looking at what each of these thinkers, Davis, Murray and Baraka, have to say about Billie Holiday, and then for something much larger than the individual that she is.

JJM What political dimensions existed in her art?

FG There are a few, the most obvious would be her singing of “Strange Fruit,” because it is the most blatantly political song, and one we identified with her from the time that she recorded it until the time that she died. It is an explicit narration of the terror of a lynching and consequently a critique of American racism at its worse. I think too that there are gender politics in the songs she chooses to sing – not so much the torch songs – but the blues songs that she sings which are almost always about interpersonal struggles between men and women in a humerous kind of way. “Fine and Mellow” or “Billie’s Blues” are about gender politics in relationships. So, that is the second dimension, and the third dimension is about jazz itself as a form, that it’s a form that insists on a certain level of freedom, and the freedom of the individual to express themselves. Jazz is about taking standard forms and completely recomposing and changing them, and there is a political dimension there that is radically democratic. All those elements are apparent from the lyrics to the music itself – the material that she chose to sing.

JJM You spend quite a bit of time talking about the image of jazz and how it has changed over the years. Why has Billie Holiday’s voice and image been so attractive to corporate America?

FG Part of that is because jazz is attracted to corporate America now.

JJM It is amazing how you can’t go anywhere without hearing it, yet people aren’t consumers of the music…

FG It is a certain moment in jazz that is attractive to corporate America, it is not this contemporary moment. It is not about a living artist, but about a certain moment that becomes about a kind of elegance and class as well as “hipness” that is very American. So, these characteristics of classic jazz are used to sell products. There is a way that advertisers sell us versions of ourself that we want to be. Billie Holiday in particular, though, because she evokes a sort of quality of longing. It’s longing for love in her songs – a union with a mate or partner – and advertisers link it to a longing for the products they are trying to sell, and a longing for the kind of lifestyle that is suggested by that. It is not just Billie Holiday. She happens to be just one of the many jazz artists in corporate America. I hear Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan, especially on car commercials, Miles Davis on computers. At this moment, classic jazz is of interest to corporate America.

JJM You see images of guys like Chet Baker a lot, or Miles Davis in a Gap commercial. You hear Billie Holiday a lot but I don’t really see her image.

FG It is interesting in the way that you see Billie Holiday. It is her style that is marketed. For example, in music videos and magazine layouts, there she is with her signature gardenia. It is definitely selling a Billie Holiday style, not Billie Holiday the woman, although her image is on everything from cups to posters to t-shirts.

JJM You quote Abbey Lincoln as saying, “I discovered that you become what you sing. You can’t repeat lyrics night after night as though they were prayer without having them come true in your own life.” Why did you choose to profile Abbey Lincoln in your book?

FG I knew I wanted to end the book with someone who was influenced by Billie Holiday. There were a number of people I could have chosen, but at the time Abbey Lincoln was someone I was listening to, and who I knew early in her career had most often been compared to Billie Holiday. Because I didn’t want to deny that there were these horrible tragic events of Billie Holiday, I wanted to suggest that there was something even in those tragic things we could learn from, including artists, who didn’t have to repeat the mistakes she made. I picked Abbey Lincoln because her performing persona is so different, even as it acknowledges the influence of Holiday.

JJM She was quite successful in moving beyond Billie Holiday and finding her own voice, not just in music, but particularly in politics.

FG Very much so. She was a very good person for closing the book. But as I watch other people even today, like Cassandra Wilson, I am interested in seeing what they do with their own legacies.

.

.

___

.

.

In Search of Billie Holiday:

If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery

by

Farah Griffin

.

.

This interview took place on June 24, 2002

.

.

.