2017 is the 100th birthday year of several jazz immortals – among them Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Buddy Rich, and, today, Ella Fitzgerald.

As a young and naïve jazz fan in the 1960’s, like Louis Armstrong, Ella seemed “square” to me – her voice too sweet and happy for my ears, especially when compared to the singer who most moved my soul to discover more of the music, Billie Holiday. Plus, the Songbook series she became internationally famous for seemed too smartly packaged, slick in a Madison-Avenue-way that tore me away from the bins that stocked her record albums.

Over the years, however, I eventually came to appreciate and cherish her, especially as I learned the courageous and inspirational nature of her biography, and played her recordings with Chick Webb, and dug the collaborations with the Ink Spots, Louis Jordan, and eventually, of course, Armstrong. (Their version of “Summertime” has to be one of the ten great vocal songs I have ever heard, which still sounds simultaneously fresh and wistful).

There is a brief remembrance of Ella by Alexandra Levine in today’s New York Times, whose highlight is this quote from Loren Schoenberg, musician and founding director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem; “…there was something about [Ella’s] voice — a purity about her intonation and her range and her style — that made musicians react to her like we could react to Pablo Casals, Jessye Norman or Yo-Yo Ma.”

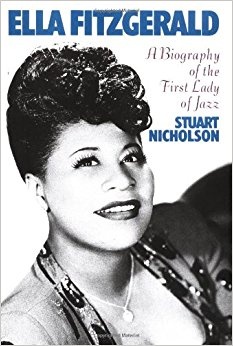

I was also drawn today to revisit Stuart Nicholson’s acclaimed Ella Fitzgerald: A Biography of the First Lady of Song, written in 1993 (three years prior to her death). Nicholson’s excellent concluding narrative gives the reader a good sense of who she was and what she accomplished.

Happy Birthday, Ella…

_____

Excerpted from Ella Fitzgerald: A Biography of the First Lady of Jazz

by Stuart Nicholson

*

From the very beginning of her career during the swing era, Ella’s voice, image, and body was never the site of sexual fantasy in the way many of the startling beauties that sang with the big bands did, such as Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Peggy Lee, and Martha Tilton. Over the years female jazz and popular singing has tended to suggest femininity as something decorative and wistful, secret and available, addressed by its very nature to men. The effect of the voice, so intimately and intrinsically a part of the singer, makes sound and image virtually inseparable. Ella somehow transcended these conventions. Her voice seemed virginal and unsullied, speaking not of empty beds and unrequited love but of the modest hopes of pubescent romance. Her role as a singer was always that of a perpetual adolescent waiting to see what life will bring. She sounded too young to have had any sexual experiences of her own; the sheer innocent enjoyment she found in the music of sophisticated love songs contradicted the passion and pathos of their lyrics. This duality allowed her to leave a song very much as she found it, untarnished by subjectivity, so that in her vast discography there is no single version of a song that can be pointed to as the definitive Ella Fitzgerald. Instead, there are hundreds and hundreds of songs where her performances show a remarkable consistency; and the better the song, the better she appears as a singer. Ella’s studio work is defined not so much by her performances as by the inherent musical characteristic of the songs themselves. Betty Carter, a brilliant jazz singer in her own right and herself the winner of a Grammy in 1989, observed: “Ella sings a ballad pretty much how the composer wants a ballad sung, because she’s going to sing it straight, no doubt about that. She may twist it a little bit on the end – maybe. She’s not going to deviate from the melody that much, but the way she approaches the melody is the important thing. Audiences liked that. They could always depend on Ella: on the way she approached the melody, the phrasing, the attack of the words, the way they sounded when she sang.”

Outside the recording studio Ella was never more alive than with a band on stage and never more inventive than when she launched into a scatted improvisation. Then imagination, humor, and sheer talent earned the respect of the jazz pantheon. This was the essence of Ella Fitzgerald.

But her wonderful voice and the priceless gift of being able to swing were in themselves no guarantee of success. To survive and thrive in the music business demands a determination to succeed that can withstand the most devastating blows to the ego. Ella, for all her performance anxieties and insecurities, has driven herself relentlessly. “She’s worked hard all her life, and she’s still working hard,” said Betty Carter in 1992. “It’s unreal how she’s working so hard, being as ill as she is. You wouldn’t bee working in a wheelchair if you’re not working for people. The woman’s doing that now. So what’s on her mind? It’s not glamour. She just wants to do what she loves; she wants to hear the applause. It’s her life, her reason for living.”

It’s ironic that Ella, who has so loved her audiences and who throughout her life has given instintingly of herself, should have remained such a lonely figure. Apart from her marriage to Ray Brown, her life has been spent in a series of affairs that have never led to the security and happiness of which she sang and which she herself sought so desperately. But she has found fulfillment through her music and in the warmth and joy she has received from her audiences. This helps to explain why Ella has concerned herself less with the quality of her material than with the effect it has on “the people.” She loves to sing, but it must be what she thinks her audiences want to hear. Sometimes she has appeared to make no discrimination between good and bad. The key has been the audience reaction: If they liked a number, then it was in. This policy has occasionally led to raised eyebrows among both her musicians and her more jazz-oriented fans. “I think she lays so much stress on being accepted in music because this is the one area of life into which she feels she can fit successfully,” said one musician who toured with her for years. “Her marriages have failed. She doesn’t have an awful lot of the normal activities most women have, such as home life, so she wraps herself up entirely in music. She wants desperately to be accepted.”

It took the Songbook cycle and Norman Granz’s careful stewardship of her career for Ella to become an internationally renowned jazz artist. Under Granz’s authoritarian direction she thrived. He imposed an underlying aesthetic in the choice of her repertoire, realizing that the twentieth-century American popular song represented an opportunity for interpretation and extemporization. These songs could be reinvented by whatever artist happened to be singing them. When Ella addressed the Songbook cycle – part jazz lieder, part cocktail music – not only did she revalidate the songs in terms that proved to be accessible to a wide public, she made her statements stick, enhancing her status as an artist beyond her wildest dreams. And in return it seemed that every time she sang those songs, they revalidated her.

Ella’s odyssey has taken her from dire poverty to the luxury of Beverly Hills via dance halls, dingy nightclubs, and segregated accommodations in a country that still totters on the racial divide. In her own unassertive way Ella has defied the traditional expectations of a black person in a predominantly white society. She has endured discrimination with dignity and given herself equally to black and white audiences, who in their turn have taken her into their hearts. She has been feted by the highest in the land and showered with awards, medals, and honorary degrees as tangible evidence of her status as a performing artist. She has been acknowledged as a legend in her own lifetime, a legend who in her later years performed before audiences that wanted to consume the aura of the physical presence of one of the great and enduring figures of twentieth-century music. “It isn’t where you came from, it’s where you’re going that counts,” she once said. And if anyone can claim to have gotten there and to have embodied the whole American Dream in the process, then it is that enigmatic, self-effacing black lady who was born out of wedlock on April 25, 1917, in Newport News, Virginia.

_____

Excerpted from Ella Fitzgerald: A Biography of the First Lady of Jazz

by Stuart Nicholson

_____

her voice skipping along, forever young

Thanks for all this insight. She was the standard to which others must be compared. It seems as if her voice, still pleasing in memory, should not be gone that long ago — but of course we still have her albums.