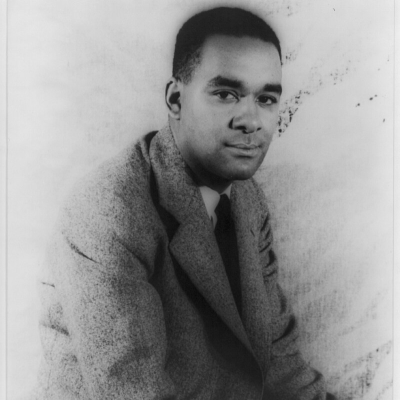

Earl “Fatha” Hines was born on this day in 1901. As one of jazz music’s most influential pianists, his work has touched the creative heart of American culture since 1925, when he first met Louis Armstrong at a Musicians’ Union poolroom in Chicago.

Hines is one of those figures who contributed to the development of jazz on a variety of levels. In The Chronicle of Jazz, Mervyn Cooke credits Hines’ “trumpet style playing” for being the “first tangible departure from the post-ragtime stride idiom, cultivating a right-hand melodic technique more directly comparable to that of front-line melody instruments.” “Weatherbird,” a 1928 duet with Armstrong, is considered one of the most important recordings ever made. His orchestra headlined the Grand Terrace Café in Chicago for 12 years, and, perhaps most importantly, was the first all-black band to tour America – including the South. (Hines would later refer to his orchestra as the “first Freedom Riders.”)

While Hines made many great contributions on a national scale throughout his career, he also made a significant impact on the growth of my own interest in jazz. In 1975, while on a tour of San Francisco’s North Beach “night life,” my companions and I found ourselves in a Broadway nightclub big enough for a piano, drum kit, and a few booths and handful of tables. My two buddies and I literally walked in off the street and were instantly no more than five feet from the legendary Hines, who was accompanied by bass, drums, tenor sax, and a wonderful singer who, in our somewhat compromised condition (we were out most of the night after a game at Candlestick) reminded us of Billie Holiday. During a set break, since we were the only patrons, we had ample opportunity to talk with Hines and his group, and I vividly remember one of my buddies — a much more seasoned jazz fan than myself at the time — telling Hines that the interplay between his saxophonist and singer made him feel like he was watching Lester Young and Billie Holiday. To this day, I recall Hines’ wide smile at that comment, and how he called his tenor player over to the table to share the observation. Drinks were shared, toasts were made, and more music was witnessed — a lifetime more, in fact.

*

You can read Hines’ New York Times’ April 24, 1983 obituary here:

_____

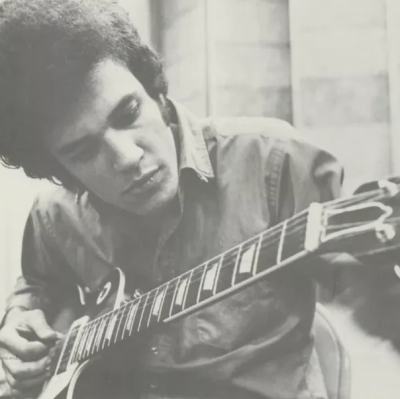

Hines plays “Memories of You”