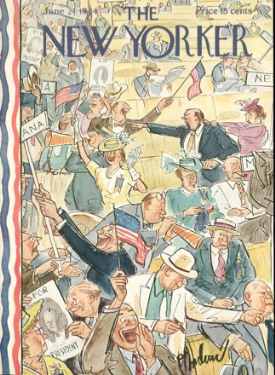

Richard Boyer’s entertaining and candid New Yorker profile of Duke Ellington first appeared in the June 24, 1944 edition under the title “The Hot Bach I.” (Parts “II” and “III” were published in subsequent weeks). Described by Ellington biographer Terry Teachout as “the most comprehensive journalistic account of Ellington’s life and work to appear in his lifetime,” the feature is filled with now well-known Ellington history (for example, his approach to composition and his appetite for food, women and the Bible), social history (Boyer’s casual description of the racial discrimination the band encounters on the road is notable), and some humorous interplay between Ellington and writing partner Billy Strayhorn, described at the time by Boyer as a “staff arranger.” The piece is a terrific companion to Teachout’s book, and another reminder of how important the The New Yorker has been to the arts over the years.

_____

The Hot Bach I,

by Richard Boyer

Duke Ellington, whose contours have something of the swell and sweep of a large, erect bear and whose color is that of coffee with a strong dash of cream, has been described by European music critics as one of the world’s immortals. More explicitly, he is a composer of jazz music and the leader of a jazz band. For over twenty-three years, Duke, christened Edward Kennedy Ellington, has spent his days and nights on trains rattling across the continent with his band on an endless sequence of one-night stands at dances, and playing in movie theatres, where he does up to five shows a day; in the night clubs of Broadway and Harlem and in hotels around the country; in radio stations and Hollywood movie studios; in rehearsal halls and in recording studios, where his band has made some eleven hundred records, which have sold twenty million copies; and even, in recent years, in concert halls such as Carnegie and the Boston Symphony. Continue reading

_____

“It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing”