.

.

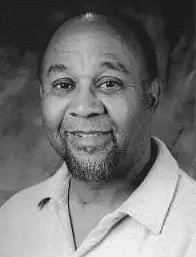

Douglas Henry Daniels, author of Lester Leaps In: The Life and Times of Lester “Pres” Young

.

.

___

.

.

…..Lester Young was jazz music’s first hipster. He performed onstage in sunglasses and coined and popularized the enigmatic slang “that’s cool” and “you dig?” He was a snazzy dresser who always wore a suit and his trademark porkpie hat. He influenced everyone from B. B. King to Stan Getz to Allen Ginsberg. When he died, he was the subject of musical tributes by Charles Mingus (“Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”) and Wayne Shorter (“Lester Left Town”), and incidents from his life were featured in the movie ‘Round Midnight.

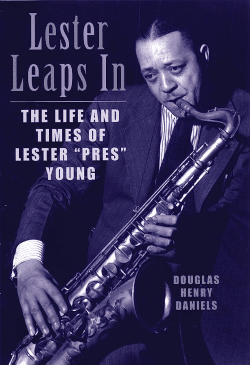

…..In Lester Leaps In: The Life and Times of Lester “Pres” Young, historian Douglas Daniels brings to life the legendary saxophonist’s world. The first ever to have access to Young’s family and many musicians who played with Young, Daniels reconstructs the world in which Young lived and played: the racism that he and other black performers faced, the feeling of home and family the performers created together on the road, and what his music meant to black audiences. Young emerges at last as a kind, gentle, and sensitive man whose friendships with other performers, loving parenting, and long career give the lie to his reputation as a troubled and self-destructive jazz artist.

…..Daniels, currently professor of history and black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, talks with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita about the tenor stylist’s life, his work, and his influence on American culture…

.

.

___

.

.

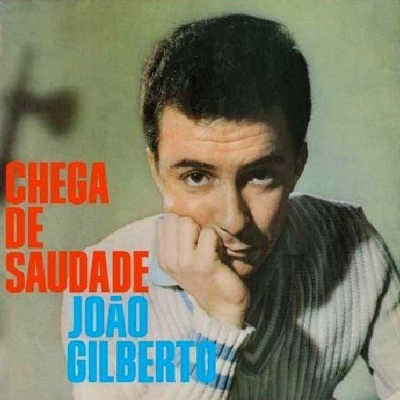

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

“Pres invented cool. Rather than state a melody, he suggested it. He barely breathed into his horn, creating an intimacy that gave me chills.”

– B. B. King

.

___

.

JJM The jazz critic Ralph Gleason wrote of Lester Young, shortly after his death in 1959, “If you don’t know who Pres was, you’ve missed a great part of America in the past 20 years.” With that in mind, I am grateful to have you visit with us and help us understand who this great American artist was.

DD Thank you.

JJM You began this book in the early 1980’s. How is your approach different from other jazz histories?

DD I take the musician’s comments and observations more seriously. For example, when they say, “Lester Young played the way he was,” I take that seriously. Or when they say “He was like a spiritual leader for us,” I probe what they mean by that. Then too, I set these comments within the larger domain of African-American history and black studies. That is to say, I do think there are black cultures and some of the comments of the musicians reflect their abiding belief and aesthetics that other writers may not write about or may not take seriously. For example, Irving Ashby said he worshipped Lester Young. I said to him, “Worship is a pretty strong word.” He said, “If there was a stronger word, I would use it.” So, that gives you an idea of the considerable impact he had on some individuals and on society. By the way, concerning that Ralph Gleason article, Lee Young, Lester’s brother, said that Gleason is one of the few people Lester let in, so to speak. He got close to Lester. It is very clear from his writing that this happened. Lee Young continually refers to that article as being the best, perhaps, that he has seen.

JJM I thought the statement communicated the importance of Lester Young to American society. You certainly point that out in your book. Lester Young’s family had roots in the countryside of Louisiana and Mississippi, but were not dirt poor. Could you describe some of the positive and negative aspects of his upbringing?

DD Well, he was born in the Deep South, and we know that the history of the Deep South in the early 20th century is characterized by an increasingly hostile environment toward African-Americans. Not only in the form of lynching, but in terms of legal racial discrimination. That is to say that in 1870 and 1880, racial discrimination was not legal in the south, but after the 1890’s, they began to pass laws separating the races and increasing hostilities between the two. We see this in the race riots that occurred, not only in Atlanta in 1906, but in Springfield, Illinois a few years later, and then in 1919 in East St. Louis and in Chicago, and in Tulsa, 1921. In these riots, white people, usually, attacked African-American communities, sometimes leveling them. These race riots were different from the ones in the 1960’s, where African-Americans looted and burned. It was just the opposite during Lester Young’s era. So, this affected him deeply, this deteriorating climate in race relations. It is part of the reason that the family left the south for the north in 1926, settling in Minneapolis. Lester’s mother played piano, and there is reason to believe she had a music school in New Orleans in the late 20’s. His father, Willis, was a prosperous “Professor” of music. He didn’t have a university appointment, necessarily, but this was the term used for musicians who could read and write music, and who were thoroughly schooled in keys and harmonies. For example, Buster Smith was often referred to as “Prof,” and sometimes bandleaders would be called “Prof,” sometimes jokingly. But they were very serious when they called Lester’s father “Prof.” He played all instruments, he taught them all. He also conducted choirs in church and taught voice. He led vaudeville bands, bands on the minstrel stage and with carnivals and bands for all occasions – dances, for example. So, he was a rather prosperous individual and to some degree Lester was “protected” by his father’s affluence and by the fact that they when they traveled in the 1920’s, they traveled in train cars kind of like Ellington and Cab Calloway did in the 30’s. This insulated him somewhat from the ravages of southern society. But, whenever they went into town, they would be subject to the taunts, or worse, of a hostile population. W. C. Handy writes about this kind of treatment in his autobiography, so all this is very well known. On the one hand Lester was protected, on the other hand he lived in a society which was so racist it made him sick. He hated racism and prejudice, it just sickened him at heart.

JJM His father championed jazz as a way to express black pride and heritage, didn’t he?

DD Yes, but he didn’t think of it as jazz, he thought of it as music. He played all kinds of music. He played church music, he played popular songs, vaudeville hits. In the 1920’s, when jazz was catching on, he knew that it was necessary to make some changes to appeal to the public, so he presented several members of the family playing saxophone. There were six of seven of them. Irma played one, Lee played one, the father, the stepmother, the two cousins. So, with the popularization of the saxophone in his band, he indicated he was willing to change with the popular currents affecting the jazz age. I don’t think he had the band play blues though, and he didn’t consciously say, “Now we are going to play jazz.” On the other hand, he did tell young musicians, “I can teach you how to play jazz.” This is how he recruited people like Clarence and Leonard Phillips, Cootie Williams, and others in the 1920’s. They were often in their mid or late teens when they would join him. He would treat them as though they were family. They would all eat together, he would protect them, etcetera. He would give them a little bit of money, but he gave them a lot of musical instruction. And, of course the opportunity to play, so he was very up to date with what was going on in American society, but he was not a jazz man per se. That was Lester.

JJM Billy Taylor said of Young, “Lester’s approach to everything he did in life was concerned with beauty.” Though he was known for alcoholism and pot use later in life, those who knew him early in his career say he didn’t drink, smoke or swear at that time. What was he like as a young man?

DD He was the apple of his daddy’s eye and he was very close to his mother, Lizetta. The family separated in 1919, and that is when Lester and the others went on the road with his father and new stepmother. But, he was a very compliant child in some ways. He was upfront, honest…Whereas other children might tell a “white lie,” Lester would tell the truth, and sometimes when he was punished by his father, he would run away. Lee Young said that Lester was running away all the time. So, while he was a model child, there was this other rebellious side, where he would stay away for days or weeks at a time, earning money as a musician. Then he would show up with no explanation for where he had been, and he would be asked no questions as to where he had gone, which was really remarkable in those days. So, he was a model child. His father didn’t swear or drink. I don’t believe he smoked, either. He was a strict “church man.” Lester was too to a degree.

JJM Lester Young was a child star. When was Young’s virtuosity first apparent?

DD The first report we get from it, come from Clarence and Leonard Phillips, two brothers who met the band in the winter of 1923. The family wintered in a small town in Arkansas, and that is where they met the Phillips brothers and a few other people. They said they were playing marches and simple things like that, whereas Lester was just blowing. He had only been playing saxophone maybe for a year or two, because he joined his fathers band at 10, and he played drums for a year or two, so that would take us up to about 1921. So, if he switched in ’21 or ’22, he was a virtuoso by ’23 or ’24, at age 15 or so.

JJM This was on alto or tenor?

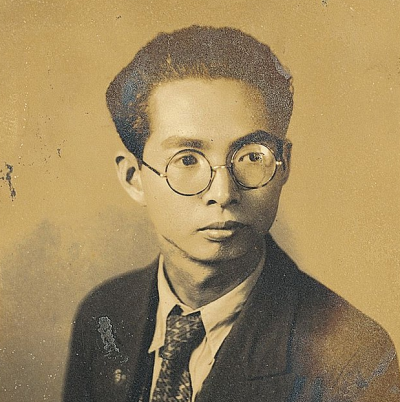

DD He played several instruments. The first photo we have of him on a saxophone is a C Melody saxophone, when he is about 12 years old. There is a photo in the book (left) of four individuals, two of them were Lester’s cousins and then Lester is on the C Melody. Leonard Phillips said that Lester played all of the saxes. He played soprano, alto, tenor, although the tenor was probably played a little less than the others. Depending on whether it was a vaudeville show or a minstrel show, he might play different saxophones. The father emphasized virtuosity, so Lester must have been introduced to the clarinet too at this time of his childhood.

JJM Was this during an era when Coleman Hawkins had already popularized the tenor sax?

DD This was when Coleman Hawkins was becoming known to people. I think it was in 1919 when he traveled with Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds, and then around ’23 or ’24, he joined Fletcher Henderson’s band. It was with Henderson that he became known as an important tenor person, but I don’t think his reputation was widespread until the late 20’s.

JJM What differentiated Young’s style from that of Hawkins?

DD People who heard Lester Young said that he played altogether different from Hawkins, whose sound was a much bigger sound that explored the deeper tones of the saxophone, whereas Lester played with a C Melody inspiration in mind. Also, while he loved the melody, he was very innovative rhythmically, and I think when you hear some of his songs, like “Lester Leaps In,” for example, you hear drum patterns as much as you hear melody, in fact more than you hear melody. He was often described as having a light, silky sound. Jimmy Heath said he wasn’t fast, he was sneaky fast, that is to say it didn’t seem fast, but if you tried to play it, you would find out just how fast it was. A lot of people said Hawkins seemed to chug along more. I think it was Sadik Hakim who said in his estimation Hawkins couldn’t swing. I find that to be a remarkable statement, but if you were to probe beneath it he would say that Hawkins’ conception of swinging was different than Young’s. He was more old style, whereas in Young, you can hear Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. He often ignored bar signatures, for example, and he had a kind of running or flowing sound that caught the attention of Miles Davis. People generally characterize Hawkins one way and Pres another way. It was really more complicated. Pres knew the whole horn, and he could play like Hawkins if he wanted to, he could get that rich, thick sound out of his horn when he desired. Much of the time he explored the higher range of the instrument.

JJM Ralph Ellison referred to “cutting contests” as “ordeals, initiation ceremonies, or rebirth.” Through the process, the musician, “finds his soul.” Did the cutting contest between Young and Coleman Hawkins, reportedly held at the Cherry Blossom in KC in ’33 or ’34, actually happen?

DD It depends on who you talk to. Mary Lou Williams is the one who gives the traditional account. She does this in Melody Maker in the early 1950’s. Mary Lou Williams is from Pittsburgh but she is associated with Andy Kirk and Kansas City jazz. She claims that there was this cutting session and Kansas City men were against Hawkins and got the best of him, especially Lester Young, who surpassed Hawkins in playing. This is the story. Interestingly, when Lester Young was written up briefly in the Chicago Defenderin the summer of 1934, they said he had taken Hawkins’ place in Fletcher Henderson’s band, but there was no mention of any cutting contest in Kansas City. Also, Pres never mentions a contest between him and Coleman Hawkins. The way he explains it, he was standing outside a club in Kansas City, waiting to listen to the Henderson band, with other local musicians, and Hawkins didn’t show up. Henderson came out and asked if any of the local tenor players could take the place of Coleman Hawkins. Since Pres could read, the others musicians told him to go on and take the chair. So, he sat in and played Hawkins’ part in everything, and did quite well. Then he says he ran down the street to his own job, where there were 13 people in the audience. Nothing was said about a cutting contest. In his autobiography, Count Basie says that despite the myths of this cutting session, he was there, and he didn’t see it at all.

JJM It is part of our history that jazz started in New Orleans and went north to Chicago and New York and then to Kansas City. You made the case for how small towns played a significant role in the development of jazz…

DD As Buster Smith said, they didn’t hear much about New Orleans back then, in the 1920’s. Other musicians, such as Eubie Blake, maintain that they were playing jazz in Baltimore. James Weldon Johnson, a lawyer and songwriter, historian, poet, novelist, claims that he first heard jazz in 1905 in New York City, and he writes about this in his history of Manhattan called “Black Manhattan,” which came out in 1930. So, I think you found the music wherever you found black people. Also, you have to remember that these musicians were extremely mobile, taking advantage of the train schedules and the roads that allowed them in the teen years and the 20’s to drive from city to city and from town to town. Lester Young was up in Minneapolis in 1926. So was Leroy “Snake” White, Eddie Barefield, and others. Barefield played with just about every band except for Ellington. Leroy White did arrangements for Ray Charles and for Desi Arnaz when he was out in Los Angeles in the 40’s and 50’s. Lester got married in Albuquerque for the first time, so he was there, his family was there and in Phoenix on the way to California, so these people were everywhere, even in the Rocky Mountain States.

JJM You wrote about how they played in Bismarck. Bismarck doesn’t exactly have a large African-American population. I think you make a good point about how music touched people of all colors everywhere.

DD Leonard Phillips said that when they were playing up there in North Dakota, they would see Lawrence Welk and his band playing in venues opposite them.

JJM Lester Young joined Count Basie’s band, and that really provided the springboard to his international fame. What was the special importance the Basie band had for African-Americans?

DD It was one of those bands that came out of a region that wasn’t known for its bands, the Midwest, and Kansas. At this time, it was the bands of Duke Ellington from New York, Fletcher Henderson of New York, Cab Calloway of New York, and so on. Basie’s band was a band of stars, furthermore of bandleaders. Buck Clayton, their trumpet player, had been a bandleader out in California for a couple of years. He had taken his band to Shanghai, where he lived for a couple of years. He was on his way to New York to play with Willie Bryant when he stopped in Kansas City. His history changed because of what he heard from the Basie band. People liked the Basie band not only because it was a band of stars and leaders. Walter Page, the bassist, had been a leader, as well as Basie. Buster Smith had been a leader. They also liked the blues that this band seemed to play. Jump blues, uptempo blues, as well as slow blues. I suspect that Basie’s band played the blues more authentically than some of the other bands, particularly some of the white bands, who were not known for their love of blues. So, that is why they liked Basie. He played blues, he played jump blues, he played ballads, and that band could really swing. Harry Edison said he had never seen a Basie performance where people did not get out of their seats and dance. We forget this was dance music. Black people come from a tradition where dance music is very important, and Basie’s band was part of that. Performances like “One O’clock Jump,” for instance, that really meant something for people. Other songs had references to African-American folklore and culture.

JJM What was the very first recording Lester Young and Billie Holiday made together?

DD I don’t know the very first one, I would have to look that up. But in January of 1937 they met in the recording studio with pianist Teddy Wilson, who was the leader at that time of the pick up group, and I think Buck Clayton was there. It was things like “This Year’s Kisses,” “Some Other Spring,” “Sailboat in the Moonlight,” which Lester liked in particular. In that year, they recorded a number of songs.

JJM How would you characterize their friendship?

DD It seemed to have been a brotherly/sisterly kind of thing. They both had, in their own ways, hard lives. Lester not quite the same way as Billie Holiday, who had been abused and raped as a child, but still, they both had to deal with the realities of racial discrimination in places like New York and Philadelphia. They also had to deal with racism in the music industry and this kind of brought them together. More importantly, their conceptions of music were very similar. She said she tried to sound like a horn when she sang, and she thought Lester tried to sound like a singer when played his instrument. They both liked to improvise, they didn’t like formal arrangements or written scores. They would just start out in a particular key and then take it from there. So, they had similar attitudes about the music. People today lose sight of how rich that music culture was at that time. It took people in, often black people, but some white people too, like Jack Teagarden, Miff Mole, Mezz Mezzrow, Bix Beiderbecke, and a host of others. It transformed the lives of a number of people. I maintain it was a kind of brotherhood. Swing society was like a fraternity or a church and they had expressions that they used to show that they were close to one another. Billie takes credit for giving Lester Young the nickname “Pres,” that is, “president” of the tenor saxophone. The reality is that the band the Blue Devils, whom I interviewed in the 80’s, took credit for giving him that name. So, they were close, but not in the way that most people think. They think they were lovers, for example, but that doesn’t seem to have been the case. It was more like brother and sister.

JJM A life transformation took place for Lester Young during his experience in the Army. How did that experience change him?

DD A lot of people say he never really talked about that experience, or if he did, he used language they couldn’t understand. So, he wasn’t much help in telling us what went on in the military, but we do have the trial record of his court martial. Some would say he was court martialed for having a white wife, while the trial record says it was for having an ounce of marijuana on him at a particular time, and some pills – maybe uppers in his foot locker along with a picture of his wife. He was put in detention barracks for the larger part of 1945. The drummer Jo Jones says he was beaten by the guards and tortured in other ways, so it is common to think that this changed his playing. I talked to Buck Clayton, and he said in his estimation Lester played better after the military experience than he had before, because he was no longer with a big band and he had ample opportunity to blow. If you listen to “Pres in Europe,” for example, which came out in the 1980’s and was probably recorded in 1956, you hear a Lester Young who is really blowing. Some of the selections are eight and nine minutes long, and much of that time is taken up by Lester Young.

JJM You suggested that reviewers’ criticism of Young during this post World War II era amounted to a kind of character assassination. What would have motivated the writers to do that?

DD Young wasn’t very cooperative with writers. He didn’t trust them. He kept them at a distance. He didn’t do a lot of interviews like a Louis Armstrong or a Duke Ellington might do. Ellington wrote articles for magazines, Armstrong did autobiographical work in the 1930’s, “Swing That Music,” but we didn’t get anything like that from Lester Young. So, he was something of an anomaly. He wasn’t out there aiming to please the writers, so they distrusted him. Then, when they learned he had been imprisoned in the military, in an era of flag-waving patriotism, and that he had been given a dishonorable discharge, they suspected something must be wrong with him. That is why they were prone to dislike him. When he tried to do things that were different, they misinterpreted it and thought he “can’t play like he used to play.” I think Louis Porter, in his work Lester Young, did a good job of analyzing Pres’ playing, and talking about the changes that he went through, and hilighted the fact that change does not mean decline. It just means change. Lester was a conscious, creative artist, who thought it was necessary to change. The music does not stay the same, it evolves. In October of 1948, he came out in a number of articles in black newspapers, claiming that bebop was a natural evolution and part of what was to be expected.

JJM He didn’t seem threatened by bebop at all. In fact, he had such an influence on Miles Davis and John Coltrane that I am sure he felt a part of it even though he may not have been associated with that group of musicians. One of the things I was curious about, continuing on this theme of the quality of his work following the war, did the circumstances of his small group pairings have something to do with the poor reception to his post World War II work?

DD It’s possible, that is to say, people loved him with Basie, and his leaving Basie was something he wouldn’t explain to them because he thought it was his private business. Nobody in the family would talk about it either. I think some writers may have resented Young, because he wouldn’t explain his decision and because he left the Basie band. How could he do that? Basie’s was such a great band! Why on earth would anybody in their right mind do that? So, I think that is a part of it too. When someone left Ellington, it was a big scene. When Johnny Hodges left, it was like he was being disloyal. There is a lot of immaturity on the part of writers who should be more responsible. Many of these writers never acknowledge that they don’t know because of the divides between black society and white society. They never admit that. These are some of the reasons they might have written that he was declining. Then, too, there were other musicians, white musicians, playing in Lester Young’s style who were getting a lot of publicity, and maybe they felt those musicians were more accessible to them.

JJM Who would they be?

DD Zoot Sims, Stan Getz, Al Cohn, the Four Brothers, you name them. All the tenor players were playing like Lester in the 1940’s. Brew Moore said, “If you don’t play like Lester, you are wrong.”

JJM Young loved the Four Brothers…

DD Yes, he liked them. He didn’t observe racial boundaries in terms of his musical tastes. He was an admirer of Frank Sinatra, for example.

JJM In fact, among his musical heroes were Bix Beiderbecke and Frankie Trumbauer…

DD Yes, he listened to them and all kinds of musicians. All of them did. They had big ears, they listened to everybody. That didn’t mean they liked it, but they knew they might learn some things.

JJM You write in your book, “The behavior associated with ‘cool’ was frequently attributed to him. In other words, he was linked to a distinctive black urban aesthetic and philosophy that underscored not only his originality but his detachment from the concerns of the world, and from the persistent intrusions of a materialistic society into African American life. In his own way, Young played a major role in spreading this ethos to musicians and fans.” Can you talk about this a little bit?

DD When I ask musicians about “cool,” they kind of laughed, suggesting that they thought the whole thing was ridiculous. They felt that this was just another term the writers take up and run with. They also say, if there is anything to “cool” in music, Lester invented it. He was a person who could play cool, even when playing uptempo, hot numbers. So, there is that characteristic in his playing. The drummer, Carl “Kansas” Fields said, “The way Lester played, that is the way he was.” I think there was a kind of unity in his conception of music and his conception of self. We are getting kind of abstract here, and this is hard to explain. Then too, I think there is some African heritage relevant here. Yale University Professor Robert Thompson has written about “cool ” in a few articles, maintaining that this “collectiveness” or “collectedness,” this ability to stand above the fray, seems to come from certain West African societies. “Cool” or “cool lifestyle,” may be deeper than meets the eye, it is just not a popular culture thing. This is how people deal with adversity, they try to stay cool, calm and collected, so that they can think clearly and see their way through some of the problems they have to deal with. With Lester, it became kind of like a cult. There are a lot of people who admire Armstrong – musicians in particular – in the way he dressed and everything, but with Pres, it was a little different. He was, without a doubt, a cult figure.

JJM He was a nonconformist…

DD Yes, they liked him because he was a rebel, too. But, I don’t think he did this to attract a following. It was the way he was, and it was the way he protected himself, by being remote, at times, with people who really didn’t understand him or the history of his people, or have a real and solid interest in the music as music. For him, music was almost sacred. He would tell a lady friend that he was playing a tune “just for you, now, and I want your complete attention while I do this.” His music came from way down deep inside. People like Bobby Scott said he was kind of a philosopher of sorts. He didn’t talk a lot, but when he did, it was very intelligent. For example, he was traveling with the Jazz at the Philharmonic in the 50’s. They were flying over the country, and he looked down at the Midwest below, and he said, “You would think there would be room for all of us.”

JJM His music came from deep down, and it touched people in profound ways. Allen Ginsberg said that “Lester Leaps In” is what he was thinking about when he wrote the poem “Howl.”

DD True, although I don’t understand how Ginsberg went from “Lester Leaps In” into “Howl,” but I am not a poet.

JJM I connect the two in this whole thing of “cool,” this nonconformity aspect that was an essential part of his persona later in his life. I think that anyone who was a nonconformist could connect with. They connected with how he held his horn, perhaps, or how he dressed, or the fact he smoked dope. Whatever it may have been…

DD Marijuana, alcohol, yes. Some people think he was a heroin addict.

JJM I think that people like Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac and these other artists who revered Young looked at him and said, “this is how I want to be, this is how I want to project myself into the culture as well.” Miles Davis used Lester Young as a model, and I suppose there is at least a little bit of Lester Young in many of us….

DD He was a major figure, not only in American music, but in American culture. A few people, like Ginsberg, recognized this.

JJM Lester Young once said, “Without originality, art or anything else worthwhile stagnates, eventually degenerates.” Could it be said that Lester Young’s early death was caused by liquor, but that his lack of originality late in his life may have caused his excessive drinking?

DD No.

JJM What caused it?

DD Nobody knows why people drink. A lot of people drink. It is a sickness. They always talk about the fact that Pres was an alcoholic, but Coleman Hawkins was an alcoholic, Ben Webster was an alcoholic, Don Byas was an alcoholic, and the list goes on and on. You hear the argument that he drank because he wasn’t creative anymore. But that is ridiculous! It is absurd! He drank because he had pain? Who knows why? Perhaps it was a physical pain, or some other kind of pain. He wouldn’t go to doctors, so we have no evidence.

JJM Al Hibbler wrote and sang a song specifically for Lester Young’s funeral called, “In the Garden.” Is that available on a recording anywhere?

DD Not to my knowledge. But there are other songs, “Lester Left Town,” by Wayne Shorter, and Charles Mingus’ “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.”

JJM I f you could give our readers 5 – 10 ultimate Lester Young recordings to listen to, what would they be?

DD “Tickle Toe” is something he liked with Basie, based on “Willow Weep for Me.” “Way Down Yonder In New Orleans” and “Lester Leaps In,” the 1944 recordings of “Afternoon of a Basie-Ite,” and “Ghost of a Chance.” Everything on Lester Young Plays with the Oscar Peterson Trio. Add one or two from Billie Holiday then a couple from his quartet and quintet. I really like the Aladdin recording done in July of 1942, Lester Young with Nat Cole. “I Can’t Get Started” and “Body and Soul.” He records five or six selections with Cole.

.

.

Lester Leaps In:

The Life and Times of Lester “Pres” Young

by

Douglas Henry Daniels

.

.

This interview took place on February 14, 2002

.

.

.

Excellent, informative insights into Lester.

I don’t remember this interview, but it sounds like me, and I like it very much. You did an excellent job.