David Maraniss,

author of

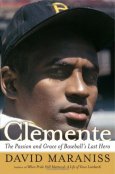

Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero

____________________

On New Year’s Eve 1972, following eighteen magnificent seasons in the major leagues, Roberto Clemente died a hero’s death, killed in a plane crash as he attempted to deliver food and medical supplies to Nicaragua after a devastating earthquake. Author David Maraniss now brings the great baseball player brilliantly back to life in Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero.

While Maraniss offers thrilling accounts of Clemente’s underdog Pirates’ two World Series victories, Clemente is more than just another baseball book. Roberto Clemente was a work of art in a game too often defined by statistics. He was also that rare athlete who rose above sports to become a symbol of larger themes, the Jackie Robinson of the Spanish-speaking world, who paved the way for waves of Latino players who followed in later generations.

While Maraniss offers thrilling accounts of Clemente’s underdog Pirates’ two World Series victories, Clemente is more than just another baseball book. Roberto Clemente was a work of art in a game too often defined by statistics. He was also that rare athlete who rose above sports to become a symbol of larger themes, the Jackie Robinson of the Spanish-speaking world, who paved the way for waves of Latino players who followed in later generations.

The Clemente that Maraniss evokes was a ballplayer of determination, grace, and dignity who insisted that his responsibilities extended beyond the playing field.#

Jerry Jazz Musician contributor Paul Hallaman talks with Maraniss about Clemente’s baseball career and of the final days of an American hero whose impact on the world of baseball and beyond lives on.

_____________________________________

“I want to be remembered as a ballplayer who gave all he had to give.”

-Roberto Clemente

_____________

A young Roberto Clemente, in the uniform of the Sello Rojo team

_____

*

Monte Irvin

_____

PH After having written this book, is it possible for you to say who Roberto Clemente was?

DM Who can know if it is possible to know who any human being is or was? It is the challenge of the biographer to try to understand somebody, and the forces that shaped him and why they do what they do. I think you can get close in those regards, but ninety percent of anyone’s life is played in their own brain, and even the people closest to them don’t really know that part of the person. I think I could understand why Clemente was the way he was, but to say that you really know any other human being is pretty difficult. You can only get so far.

PH As a biographer, was Clemente more of an enigma than your earlier subjects, Vince Lombardi and Bill Clinton?

DM A little more than Lombardi, but no more than Bill Clinton, who was contradictory and sort of hard to figure out. But it was during my work on the Clinton book when I figured out my philosophy of biography and dealing with humans, which is that every human being is a bundle of contradictions.

PH Clemente’s childhood was spent in Carolina, Puerto Rico. What were his parents like?

DM His father Melchor was a foreman in the sugar cane fields of Carolina, and his mother Luisa also worked as, among other things, a butcher. Clemente would often say that he got his strong right throwing arm from his mom. Although Clemente was born in 1934 — in the heart of the depression — they weren’t poor by Puerto Rican standards. He had several older brothers and an older sister, who tragically died when Clemente was an infant. She burned to death on a stove outside her house, which was a family trauma.

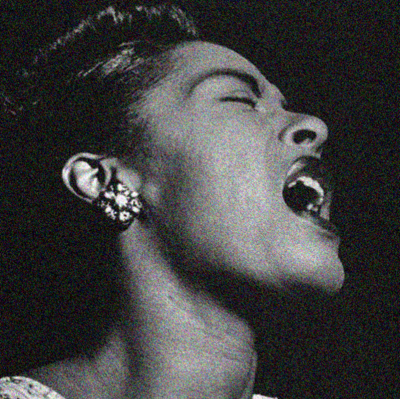

All anyone remembers about Roberto Clemente is that from a very early age he always had something in his hand that resembled a ball. It may have been a roll of tape, or a sock or bottle caps — whatever it was, he was always throwing something. He loved baseball, and would take the bus from Carolina to San Juan to watch the Winter League baseball games. In that era, many of the Negro League stars who played in the United States would go play there. Clemente’s first hero was Monte Irvin of the Negro League’s New York Eagles, and who later played for the New York Giants. Clemente was kind of a shy kid, and he would stand outside of Sixto Escobar, the stadium where Irwin played, and wait for him to walk by so he could carry his suit bag into the stadium.

PH Eventually Clemente was discovered by a Dodgers scout, Al Campanis.

DM Yes. Campanis came over from Cuba, where he had been coaching. He was a scout in Puerto Rico too, and his first scouting report gave Clemente all “A’s.” The Dodgers signed him to a bonus on the basis of that report. Clemente very much wanted to play in New York because it was a place he had heard of — there was, of course, a very strong connection between Puerto Rico and New York City. He also wanted to play there because he had some relatives in New York. After he signed as an eighteen-year-old bonus baby with the Dodgers, he went to Montreal, which was the Dodger’s AAA affiliate club in the International League. After he joined the team, Clemente didn’t really know what was going on for awhile because they weren’t playing him, and in fact they were trying to hide him. Since they didn’t put him on their forty-man roster, he only got to play occasionally. It was the most frustrating season of his baseball career.

PH His living in Canada must have posed some interesting challenges for him

DM It was his first time living outside of Puerto Rico, so it was particularly interesting since he was dealing not with just one new language, but two — French and English. He knew a little bit of English, and the daughter of the French-Canadian he was living with knew some English, so he communicated with her. His roommate was a Cuban shortstop named Chico Fernandez, who was playing every day, and who spent much of his time counseling Clemente not to give up and to hang in there, that there were reasons why he wasn’t playing. The real reason was that the Dodgers were trying to hide him from anybody who may draft him in the supplemental draft.

PH But they couldn’t hide him from Branch Rickey, could they?

DM That’s right. By this time, there was no love lost between Rickey and Walter O’Malley of the Dodgers, who had let him go. So, he hated the Dodgers. He was now trying to rebuild the Pittsburgh Pirates, and had the help of two great scouts, Clyde Sukeforth and Howie Haak, both of whom knew about Clemente. They would go up to watch the Montreal team play, and even if Clemente didn’t get into the game, they would see him in batting practice or fielding practice before. They had him earmarked as their top pick, and wound up stealing him from the Dodgers after the season was over.

PH After Clemente was signed by the Pirate organization in 1955, he experienced a segregated spring training camp in Fort Myers, Florida. Can you talk a little about that?

DM Yes, it was absolutely segregated. The first black player, a second baseman named Curt Roberts, had come before him. Clemente and the other black players on the Pirates didn’t stay with the rest of the team at the downtown Fort Myers hotel, but instead stayed with black families who lived in the poor neighborhoods of the community. When they traveled to other spring training games, they usually couldn’t eat in the restaurants the white players did, so they would have to stay on the team bus. That infuriated Clemente so much that he demanded the general manager buy a station wagon for the black and Latino players to travel in so they wouldn’t have to be subjected to waiting for the white players while they ate. This went on for the first eight years of Clemente’s career. Imagine that in the spring training of 1961 — the year following the Pirate’s World Series victory over the Yankees — Clemente couldn’t attend the celebration the team held because it took place at a country club that didn’t allow blacks! Here he was, the star of the world championship baseball team, a man who was treated as a hero in Puerto Rico when he went home that winter, yet unable to play in the spring golf outings with his teammates because of segregation. That spring of 1961 was during the early stages of the civil rights movement, and black players — Clemente being among them — were starting to say “enough of this.”

PH While he wanted to sign with one of the New York clubs because of its rich culture and his connection to family there, he wound up in Pittsburgh, which, as you point out in your book, lacked a significant Hispanic community. His life in Pittsburgh was pretty challenging, wasn’t it?

DM Absolutely. Pittsburgh of that era had no Latino population to speak of, so he faced a double barrel of race and language. For many years, he lived with a family in a black neighborhood of the Hill District, but he was still somewhat apart because of the language barrier. That made it a difficult situation, along with the fact that Pittsburgh was not an easy place to live because it was a quintessentially white, blue collar, ethnic town. It took a long time for Clemente and Pittsburgh to find one another, but it eventually happened, which is a testament to both of them.

PH The Pirates had a dream season in 1960, yet Clemente was passed over in the Most Valuable Player voting…

DM He was passed over for the entire decade, and in that year, not only was he passed over, he finished eighth in the voting. He also discovered that one of the leading Pittsburgh sports writers was actively campaigning against him. So, he wasn’t just upset because his teammate Dick Groat received the award, or that several other less worthy people like Lindy McDaniel of the Cardinals got more votes, he was most upset because some people really didn’t want him to receive any recognition, which infuriated him all winter. When he came back from San Juan that spring, he was angry and determined, which fueled him for the entire incredible decade of the sixties, when he was the best hitter in the National League.

PH Clemente was pretty outspoken about being overlooked. At the 1961 All Star game, he said, “I had the best year in the majors, but I didn’t get one first place vote.” In fact, he did get one first place vote, nonetheless it was quite a snub considering the year he had in 1960.

DM When a team that isn’t expected to win the pennant has a successful year, it is usually because they get off to a brilliant start and then carry that magic through the rest of the year. Most people acknowledge that Clemente was the spark plug on the team the entire season, and in particular he carried the Pirates during April, May and June. He then finished the season with the most runs batted in on the team, and had one of the greatest right fielding seasons in history. Despite this, he finished third in MVP voting among his own team behind Groat and Don Hoak. He wasn’t upset that Groat and Hoak or any of his other teammates got this recognition — he just felt that he was overlooked because of his race and language.

PH He was constantly being quoted by American newspapers in broken English

DM He was a very intelligent man, and he was reduced to something less than that by sportswriters who didn’t know any Spanish. That was not something he took lightly.

PH Interestingly enough, even the Pittsburgh Courier — the major black newspaper at the time — did the same thing.

DM Yes, that’s right. He had some tension with that paper, who questioned him about whether or not he considered himself to be black. It was very interesting for me to research the back issues of the Courier and study Clemente from that perspective, which I don’t think had been done before. They really covered black baseball players throughout the major leagues with a depth and warmth you didn’t see from the mainstream press.

PH How long did it take for you to complete this book, and what were some of the sources you used?

DM It took about three years to write the book. I took two extended trips to Puerto Rico, where I interviewed many people, including his widow, brother, sons, and several of his old buddy ballplayers like Vic Power, who happened to be one of my favorite players when I was a kid. I also traveled around the country to interview old Pirate players, several of whom still live in Pittsburgh. I did a lot of research at the Library of Congress in Washington as well. It turns out that Branch Rickey’s papers are housed there because of his sociological importance in American history — specifically bringing Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers and breaking the color line. Rickey had voluminous records, which helped me learn about the Pirates of the 1950’s. The Pittsburgh Courier was a major source, and I also had help from friends and researchers who looked at papers in Fort Myers as well as in Pittsburgh. The final one-fifth or so of the book is about the plane crash that killed Clemente, and it took a lot of effort to finally get all of the internal documents on the crash as well as the depositions of people who were involved with the plane beforehand. That was really the major reporting coup of the book.

PH The final days of Clemente’s life were spent in response to the major earthquake in Managua, Nicaragua, a few days before Christmas in 1972.

DM Yes, it is a tragic and depressing story, because it could have been prevented. It is also a very heroic story. Clemente had been in Nicaragua a month earlier as the manager of the Puerto Rican team entered in the amateur World Series. When he heard about the earthquake on December twenty-third, he immediately went into action. He organized a committee in San Juan and raised money for, among other things, medical equipment and food to be sent to Nicaragua. He leased a plane that took two planeloads of humanitarian aid to Managua, but then received reports that it was being diverted by Anastasio Somoza, who was the strong-arm leader of Nicaragua at that time. Clemente felt that if he went, the aid would get to the people.

So, he got on a DC-7 that was purchased a few months earlier in an area of the Miami International Airport they called “Cockroach Corner,” which is where the tramp airline operators bought and sold their crummy old planes. If there ever was a plane that should not have been allowed to take off, it was that plane. The owner didn’t know how to fly it, yet he was the co-pilot on the ill-fated flight. The pilot was someone the owner rounded up, and he had several violations against him. For one thing, he was being chased by the Federal Aviation Administration because he had sixty-six earlier violations for taking off in planes that never should have left the ground. On top of that, he hadn’t slept for thirty hours. There was no flight engineer available, so he rounded up a mechanic to be the flight engineer. In addition to all this ineptitude, the plane was overloaded by five thousand pounds. That was the plane that Roberto Clemente unwittingly boarded, not knowing any of that history. The plane never should have been allowed to take off.

PH Throughout the course of your biography, you write about how Clemente had premonitions that he would die in a plane crash, and that his wife Vera would survive him. Yet here he was, on a deathtrap of an airplane on New Year’s Eve — a holiday he traditionally spent with his family.

DM I do think he had a fatalistic streak because he talked many times about having a feeling that he wasn’t going to live to be an old man. And, while he had nightmares about a plane crash, he also told his friends that he could die from falling off a horse. It remains a mystery to me why he got on that plane. The front wheels were off the ground and the back wheels were squished, so it was pretty apparent that something was funny about the way it was loaded, but he got on because he trusted the pilot and the owner. It barely got off the ground and crashed into the Atlantic, where it broke into countless pieces. His body was never found.

PH You devoted a chapter of your book to the aftermath of the crash, and write of the Pirate catcher Manny Sanguillen, who actually skipped the memorial service to join the diving team that tried to locate Clemente’s body.

DM Clemente wasn’t a saint, but he was beloved for a lot of different reasons by most of his teammates, the people of Puerto Rico and baseball-playing Latin America, and eventually by all of Pittsburgh because he lived with such a beauty and dignity, and because he died so heroically. Manny Sanguillen was like his little brother on the Pirates — he was the one guy who could tease Clemente mercilessly, but he adored him enormously. Most of the Pirates couldn’t believe that a prince like Clemente could die, and Sanguillen was actually the one who tried to dive in and find his body. He was so moved by his “big brother.”

PH As you said, Clemente was not a saint, and he had his tough side.

DM That’s right, even to the point where he once decked a fan he thought was trying to harass him outside of Connie Mack Stadium, knocking some of the nineteen-year-old kid’s teeth loose. At times he displayed an attitude that bordered on arrogance, and he had a flash temper, particularly when he thought he was being misunderstood by sports writers. He was a human being who possessed all of the frailties common to humanity, but he was also someone whose character grew over the years — he didn’t have or need an agent to encourage him to visit sick kids in hospitals or get on that plane to Nicaragua. He often gave a speech about helping people, telling the audience that they are wasting their time on earth if they don’t. That was really one of the things that drove him, and it ultimately drove him to his death.

PH Early in your book you wrote, “To borrow the words of the Puerto Rican poet Enrique Zorrilla, what burned in the cheeks of Roberto Clemente was ‘the fire of dignity.'” He was a very dignified man, and in addition to the anger about being unappreciated, he was quite sensitive about the implication that he was obsessed about his health, to the point of being a hypochondriac.

DM Yes, and he came back and remarked that hypochondriacs don’t produce like he does. I am a hypochondriac, and I know one when I see one. Clemente was a hypochondriac, but he wasn’t a slacker in any way, he was just always worried about his health. His teammates remember that on days he complained about his health, they would say the opposing pitcher had better watch out because Clemente will probably go five-for-five at the plate. It is true that he constantly complained about how he felt, but there was a physical root to the problems — a traffic accident he got into with one of his brothers during the winter of 1954, which affected his neck and vertebrae. He never quite recovered from that accident because he had back and neck problems for the rest of his life.

PH He studied a lot about chiropractic care…

DM He was an amateur at it, but he was terrific at massages. He was way ahead of his time, and tried to find non-invasive ways to treat his physical problems.

PH He was famous for his neck rolls at the plate. I used to play sandlot ball with my cousin Pete Peronis, who imitated Clemente’s entire routine — the walk, the way he held his bat behind his head, the neck rolls

DM That is what baseball is all about, and Clemente certainly had the idiosyncrasies that any young kid could mimic.

PH Yes, complete with being a bad ball hitter. He never met a pitch he didn’t like.

DM It is easy to imitate Clemente walking to the plate, but much tougher to imitate his success at it.

PH You can’t talk about Clemente without discussing the famous San Diego abduction story, which you describe in the book.

DM Yes, and who knows if it really happened? The story is that after a game in San Diego, he was going to a place that sold fried chicken — a place Willie Stargell bought chicken from before — and as he was crossing the street, a car pulled up and three or four guys blindfolded him, took his wallet, and abducted him, supposedly taking him to a park. Eventually they realized that the man they abducted was Roberto Clemente, and they gave him back his wallet and chicken. So he was someone even the thieves revered! I am not certain how much of this story is real, but it definitely reflects the way Clemente was regarded.

PH Clemente played a role in the birth of free agency, and was there as a Pirate player rep

DM That’s right, he was there at the dawn of the freedom for players. He was a member of the Major League Player’s Association at the end of the sixties, which was the time when Curt Flood appeared before the executive board and said he was going to challenge the reserve clause. Clemente told them the story about how he had no control over his own baseball career, and how he had wanted to play in New York but was unable to because he didn’t have any say in that decision. According to the people I was able to interview who witnessed this, Clemente was very instrumental in solidifying support for Flood and his challenge to the way the owners had controlled everything in baseball for so many decades.

PH There are so many incredible exploits of Clemente’s as a player. One came at the end of his career, against the Orioles in 1971, when he had one of the great World Series performances ever.

DM I don’t think anyone has ever dominated a World Series the way Clemente did that year, and not just at the plate, where he hit .414, but in the field and on the bases as well. His presence in the dugout alone had an aura that really helped carry the Pirates to that great upset. The wonderful baseball writer Roger Angell said it was as close to perfection as anything he had ever seen on a ball field.

When I interviewed Earl Weaver, who managed the Orioles at the time, he told me the key play in that whole Series was not one of Clemente’s line shots to right center, or the great throw he made from deep right to third base, but it was when he hit a dribbler between the mound and first base. He described how startled his pitcher Mike Cuellar was after picking the ball up and seeing Clemente sprinting toward first base with his batting helmet flying — so startled, in fact, that he threw the ball away. Weaver said that Clemente’s hustle on that little dribbler was the turning point of the entire Series.

In terms of Clemente’s life, this was a very important time for him. After the seventh game he was able to be in the spotlight alone, where he finally received the national recognition he felt he had long before deserved. With the national television cameras on, he said that before he would answer any questions, he wanted to say something in Spanish to his parents back in Puerto Rico. It was a moment that had incredible reverberations of pride and dignity throughout the Spanish-speaking world. This moment, combined with the way he died, made him a legend.

PH The White Sox manager Ozzie Guillen did the same thing following the 2005 series

DM Yes, he did, and he really did that in honor of Clemente. Guillen has said that he has a little shrine in his house in honor of Clemente, so he lives on in so many ways with the rise of Latinos in major league baseball.

PH Latinos make up almost thirty percent of all the major league players now.

DM Yes, and that number will keep rising, probably. Clemente was in that first wave — he wasn’t the first Latino, but he was the greatest of the first wave. He was the first one in the Hall of Fame, and clearly is the patron saint of Latino major leaguers.

PH Vic Power was a Latino first baseman who had a flamboyant flair around the bag. Both he and Clemente were criticized in the press and by some fans for their flashy defensive styles. Can you talk a little about this?

DM I loved interviewing Power for the book, and was extremely saddened by his passing. He and Clemente were two of the greatest fielders in baseball history, and they had very different personalities around their talent. Power used to say that if he was supposed to play first base with two hands, he would put gloves on two hands. He laughed at the criticism of his style, saying that is just who he was. He made a joke out of everything. Clemente, on the other hand, would be furious at that type of criticism. They were peerless, jazzy, cool fielders, yet they both had to deal with the stereotype of being show-boaters.

PH Clemente had the basket catch, which was the same way Willie Mays caught the ball.

DM Clemente didn’t learn it from Mays, though. He learned it from playing softball in Puerto Rico.

PH What are the chances of Major League Baseball retiring Clemente’s jersey number, #21?

DM I don’t really have strong feelings about that, although it probably won’t happen for one very practical reason, and that is that Bud Selig is from Milwaukie, and how do you retire Clemente’s number but not Henry Aaron’s? So, I don’t think it will happen, but I think Clemente is honored, and will be honored more as time goes on. The truth is that anyone who wears that number — which is a favorite number among Latino players — is honoring and remembering him.

_____________________________________

“Always, they said Babe Ruth was the best there was. They said youd really have to be something to be like Babe Ruth. But Babe Ruth was an American player. What we needed was a Puerto Rican player they could say that about, someone to look up to and try to equal.”

-Roberto Clemente

_____

El Artista, by Ismael Miranda

*

Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero

by

David Maraniss

*

About David Maraniss

David Maraniss is an associate editor at The Washington Post and the author of the critically acclaimed bestsellers They Marched Into Sunlight, When Pride Still Mattered, and First in His Class. He won the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting and has been a Pulitzer finalist three other times. He lives in Washington, D.C., and Madison, Wisconsin, with his wife, Linda. They have two grown children.

*

Roberto Clemente products at Amazon.com

David Maraniss products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

This interview took place on April 4, 2006

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Jackie Robinson biographer Scott Simon

_______________________________

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

# Text from publisher.