.

.

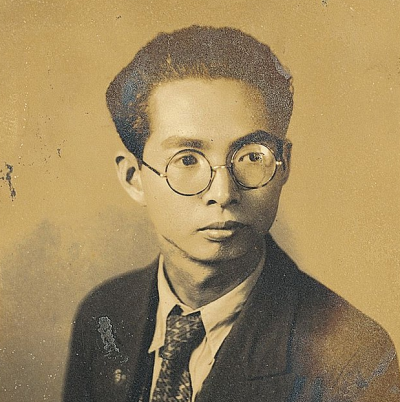

Erroll Garner on the cover of Magician, the final studio album of his life, and one of 12 albums he recorded for his Octave Records label, all of which have recently been remastered and reissued by Mack Avenue Records

.

___

.

…..The legendary pianist Erroll Garner is one of the most celebrated and popular performers in the history of jazz music. The immortal swing pianist Mary Lou Williams once tried to teach Garner to read music but stopped when she realized that “he was born with more than most musicians could accomplish in a lifetime.” The late pianist Geri Allen, who was director of the jazz program at the University of Pittsburgh – Garner’s home town – and who subsequently worked with the Erroll Garner Jazz Project, said Garner “personifies the joy of fearless virtuosity and exploration,” and “blurred the line between great art and popular art.”

…..Although he never did learn to read music, throughout his prolific 40 year career Garner published over 200 compositions, among them “Dreamstreet,” “Nightwind,” “Solitaire,” and, most famously, the storied “Misty,” a song he was inspired to write while watching a rainbow from an airplane. That song became, according to the American Society of Composers, Artists and Publishers (ASCAP), the twelfth most popular song of the 20th century, and since 1954 has been recorded by more jazz artists than any composition other than Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll.” His 1955 album Concert by the Sea remains one of the biggest selling jazz recordings of all time.

…..Garner’s immense popularity with audiences was also shared by jazz pianists, who viewed Garner’s mastery of the instrument with awe. But his impact on fellow musicians wasn’t limited to their admiration of his virtuosity. At the height of his mid-1950s popularity, Garner had a unique contractual arrangement with his record company, Columbia, which allowed him the right to approve any music before it was released. In 1959, after Columbia released recordings without his permission, he successfully sued the label, forcing them to remove the album from their catalog. This fearless advocacy for creative freedom – in partnership with his manager Martha Glaser – set the stage for artistic empowerment in the recording industry that remains today. His victory over Columbia was the first of its kind for any American artist, and compelled him and Glaser to subsequently create Octave Records, for whom Garner recorded 12 albums in the 1960’s and 70’s.

…..Now, in a collaboration of the jazz label Mack Avenue and the Erroll Garner estate, over the last year these Octave albums have been newly restored and released in expanded editions, each featuring a recently discovered, unreleased bonus track. These albums have reinvigorated interest in Garner’s creative and political impact, and brings the work of The Erroll Garner Jazz Project into focus.

…..In a July 27, 2020 conversation with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita, the historian and most eminent jazz writer of his generation Dan Morgenstern and pianist Christian Sands – the Mack Avenue Recording Artist who also serves as the Creative Ambassador of the Erroll Garner Jazz Project – discuss Garner’s extraordinary legacy.

.

.

___

.

.

photo from Institute of Jazz Studies

Dan Morgenstern

Jazz historian and archivist, author, editor, and educator; chief editor of DownBeat magazine (1967 – 1973); seven time Grammy Award winner for Best Album Notes; recipient of ASCAP’s Deems Taylor Award for his books Jazz People (1977) and Living with Jazz (2005); led the Institute of Jazz Studies for three decades.

.

.

photo: Anna Webber

Christian Sands

Mack Avenue recording artist and Creative Ambassador for the Erroll Garner Jazz Project; mentored by pianist Dr. Billy Taylor; studied at the Manhattan School of Music; Steinway artist; American Pianists Association Jazz Fellowship Awards finalist; has recorded and performed with Christian McBride, Marcus Strickland, Gregory Porter, Jason Moran, Geri Allen, and many others.

.

.

___

.

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Erroll Garner, New York, N.Y., sometime between 1946 and 1948

.

“Garner gives his listeners full value, sharing with them his joy in making music. He is one of those rare beings who is able to achieve total communication through his art. Moreover, he can do this consistently — a seasoned Garnerite will know when the pianist is really inspired. But even on an ‘average’ night, hearing Garner is an extraordinary experience.”

-Dan Morgenstern, from his review of a 1965 performance of Erroll Garner at New York’s Village Gate

.

.

Listen to Erroll Garner play “Autumn Leaves,” from the 1955 Columbia Records album Concert By the Sea

.

JJM Welcome Dan and Christian. It’s a privilege to have both of you here to talk a little about the fabled pianist Erroll Garner. Christian, what is the goal of the Erroll Garner Jazz Project?

CS When I talk about the Erroll Garner Jazz Project I like to use the word “resurgence.” The Project’s goal is to tell the story of Erroll Garner and ask the question, “What happened?” When I talk to the younger generation of musicians and mention Erroll Garner, some of them don’t know who he is, so we are reintroducing him, and shedding light on his work and performances.

DM You are right, Christian, there are too many young people who don’t know who Erroll was, and that’s a great tragedy because his music is so approachable. Susan Rosenberg [President of Octave Music and Director of The Erroll Garner Jazz project] is doing a terrific job of reissuing his beautifully remastered Octave recordings, which I have been indulging in. I know all these recordings, and have had them for years, and the sound is so great on them.

CS Thank you, Dan. We have been working really hard. [Reissue producer] Peter Lockhart has been working tirelessly to make these records sound new, and I am so happy to be a part of telling this story of Erroll Garner.

JJM Christian, how did you discover Erroll Garner?

CS As a pianist, Erroll is in my playing just like it is in every other pianist’s playing, whether we realize it or not. I was introduced to him just from hearing his name, just as we hear of Earl Hines or Teddy Wilson, but you don’t truly know Erroll unless you study him, and I didn’t really study him as a young musician until I started working with Dr. Billy Taylor. He introduced me to his style of playing on a surface level – you know, helping me understand that his left hand has this Freddie Green quarter-note thing happening, and the right hand is free to do what it wants, and there are also some octaves involved – but I didn’t really dive into his music until I became involved with the late pianist Geri Allen. She was already involved with the Erroll Garner Jazz Project, and was in the process of doing a new project with them, which was performing Garner’s entire Concert by the Sea album at the Monterey Jazz Festival, and she asked Jason Moran, Russell Malone, Victor Lewis, Darek Oles and myself to perform with her as part of this three-piano tribute to the recording. While preparing for that show, Geri and I got together in New York City a few times and went through the music of the record and dove into his performance, from how he introduced each song, to how he is played his solos, to what he did with his left hand.

Following that, Geri and I would perform in duo Garner tribute concerts, but unfortunately she became ill. She wanted me to be a part of the Erroll Garner Jazz Project, so she had a conversation with them, which led me to taking on the responsibility of introducing him to the younger generation via social media. Unfortunately, Geri passed away so I inherited all of the work she was doing, which left me with some very big shoes to fill. So this work is definitely because of Erroll, but with the undertone of Geri Allen, who was also my teacher. Just about every time I play, it is for Geri too.

DM Geri was a beautiful person and a great pianist. I had the pleasure of serving with her on the board of the Mary Lou Williams Foundation, so I got to know her and her work. Such a tragedy that we lost her.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Erroll Garner play “Mack the Knife,” a live performance from the 1963 Octave Records album One World Concert

.

.

JJM Dan, in your review of Garner’s 1965 performance at the Village Gate, you wrote that “to catch Garner in person, especially in a club, is one of the most gratifying and joyous experiences in jazz today.” What was it like to witness an Erroll Garner performance?

DM Erroll had this very special quality which can only compare to Louis Armstrong. He had an aura about him – all he had to do was walk on stage and sit down at the piano, and he already had the audience in his hands. He didn’t say a word, and didn’t have to say anything because what he did musically spoke a million words and immediately drew you into his creative world.

His introductions to his tunes were beautiful and very special – and they were real teasers and musical puzzles that had you guessing what the song was going to be. It was also remarkable how he could make an audience laugh – he didn’t have to say or do anything, his humor came from these musical teasers within the introductions. By the time he got into it, and the rhythm section joined him, they took off and the audience would applaud enthusiastically. It was a very special thing, and it was his own invention.

He was so warm in a club, and as an audience member you felt special to be in his company. Musically, he had a sound he could get out of a piano that you could compare to a great classical pianist, or to Art Tatum, who of course was an idol of Garner’s. There is a story about Tatum, who from his bed toward the end of his life told Oscar Peterson to “watch out for the little man,” meaning Erroll Garner. I don’t know whether that is a true story or not, but I have to admit it’s a great story!

JJM He was a sensational player, but I wonder if his brilliance was taken for granted?

Erroll Garner at the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam in Nov. 1964

DM I don’t think so. He was one of the few really great jazz musicians who also became very popular, along with Louis, Ellington, Benny Goodman, and in the age of the guitar, Wes Montgomery. Erroll did it purely with music – he didn’t sing, he didn’t act, he didn’t talk, he only played the piano.

Whether it was in a club or a concert hall, it didn’t take more than 30 seconds for him to have the audience in his hand. It was just a remarkable thing to witness. Part of it, of course, is that he had exceptional rhythm – he could swing his ass off – and what he did was so melodic it allowed him to reach people who had no particular background in music.

CS I never witnessed him perform in person, of course, but being involved with this project has allowed me to listen to him play in different settings, and, like Dan said, it is absolutely remarkable. There is always something new to hear, always something that surprises, and always something that grabs the listener’s attention, as Dan said, in the first 30 seconds. What is interesting to think about is that during his era, a lot of people had different acts to show their artistry – they sang, they dance, they tap-danced – but Erroll just played piano, and he didn’t even introduce the songs. You try that today and it might split the room. He was just such an incredible performer, and he played with such elegance.

JJM Dan, in that same review of his 1965 Village Gate performance, you wrote, “Because Garner has committed the sin of being accepted by the general public, certain jazz critics attempted to dissect and downgrade his art.” In particular, there was a negative portrayal of him in a 1958 Saturday Evening Post article in 1958 that referred to him as a “self-taught master improviser who couldn’t read music.” Did he struggle with how people thought about him and his music?

DM He was immune to all that stuff. I don’t think he ever read a review of his playing, and I don’t think he cared about that. His manager Martha Glaser took care of that. He loved what he was doing, and certainly the public accepted him, so what did he care about critics?

That attitude about critics goes for a lot of musicians. Louis was the same way – people would put him down for being an “Uncle Tom” or whatever, but he didn’t give a damn. Ellington was a little sensitive when critics took down a very ambitious piece like Black, Brown and Beige, but Erroll didn’t care at all. But I cared, especially when I would read some of my fellow critics put him down for the reason of his being popular, which tends to make any musician suspect with critics.

JJM And he didn’t read music…

DM Yes, that’s right. Early in my career I was working at the famous Colony Record Store on Broadway, where Erroll was a customer. He had a privilege that nobody else had – he was allowed to go behind the counter and go through the entire inventory and look for whatever he wanted. And, what did he buy? He bought what at the time was called “mood music” – artists like Percy Faith and Mantovani – because he was very concerned about playing tunes the right way, and since he couldn’t read, these particular types of records were played very closely to how the music was written. So if he wanted to learn a tune accurately, with all the chord changes and everything, that is what he would listen to. It was like his “fake book.”

It was very interesting. He would come into the store and go behind the counter, get up on a ladder, and grab a bunch of records. He would do this before going out on the road so he’d have something to listen to and so he could learn some new tunes.

JJM You said Martha Glaser cared about what the critics said…

DM Yes, she would get upset when someone gave him a stupid review.

JJM Martha was critical to his success…

Erroll Garner and his manager Martha Glaser

DM Erroll would have managed without Martha just because of his sheer talent, but whether he would have achieved the height of his fame and found financial success without her is unlikely.

I got to know Martha real well. She wasn’t related to Joe Glaser [Louis Armstrong’s manager], by the way, and she used to get angry when people thought she was. She was a wonderful lady, who today would be considered an “activist.” As a young woman she was involved in civil rights, which was somewhat unusual at the time. She worked for Norman Granz in the early days of his Jazz at the Philharmonic productions, and their strong advocacy for Black rights is what they had in common. Trummy Young, the great trombonist who may be best known today for his work with Louis Armstrong’s All Stars and who was also a star in the Jimmie Lunceford band, was an early Jazz at the Philharmonic guy, and he told me that everything Norman learned, he learned from Martha.

She was a great person. I remember that Martha was an insomniac, and she would occasionally call me at 3:00 AM to talk. She would apologize for calling at such a late hour, but she needed someone to talk to, and I didn’t mind at all because we had some terrific conversations. She had wonderful stories and a great sense of humor, so I didn’t care if I lost a few hours of sleep.

JJM Martha did an important thing on behalf of Erroll Garner, standing up to Columbia Records, who released songs from his back catalog of studio recordings without his consent…

CS Martha was a pioneer herself. Listening to Dan talk about her reminds me of all the work she has done, not only for Erroll, but also for artists in general.

Martha was so involved with everything. One example is a few years ago we came across a bill of Erroll’s that was paid in the 1960’s or 70’s, and were interested in tracking it down. We discovered it paid for a storage unit in New Jersey. We didn’t know what was going to be there, and thought it could have been something like a small crate of records or paperwork. When we got there, to our surprise it ended up being seven or eight crates of things of Erroll’s – curtains, suits, ties, shoes, contracts, accolades and various memorabilia.

One of the boxes contained what looked to be questionnaires Martha had sent to venues where Erroll played, asking them to review how he played, and asking questions about what his attitude was like, what songs the audience responded most favorably to, what the hotel accommodations were like, and that kind of thing. And on the bottom of this paperwork she asked if any celebrities were in the audience, and you could see the names of so many of the celebrities from all walks of life who attended his shows. So Martha had everyone very involved, and the amount of detail she managed was incredible.

Regarding the Columbia law suit, Erroll and Martha – this brilliant African American artist and his female manager – took this giant corporation on in the late 1950’s/early 60’s and won, becoming the first artist of any color to stand up to a major record company and retain the rights to his own material. I have to believe that without Martha, this wouldn’t have worked out for Erroll. He was amazing, but Martha really was the foundation for a lot of the things Erroll’s career was built on.

DM That’s absolutely right. Without Martha, Erroll certainly would have been known, but he never would have reached the stage that he did. At one point in time he was actually the highest paid jazz performer – nobody made more money per concert or tour than Erroll – and that was Martha’s doing. She was tough. Martha didn’t take any shit from anybody.

To expand a little on the lawsuit, Columbia put out a couple of LP’s of Erroll’s which had not been cleared by Martha, and she cracked down on that in no uncertain terms, taking them to court over it. By doing this and winning, she and Erroll were pioneers in expanding the rights of musicians concerning what their record label could release. Martha was very important.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Erroll Garner play “Three O’Clock in the Morning,” from the 1965 Octave recording Now Playing: A Night at the Movies

.

JJM Following the Columbia lawsuit, they started their own record company, Octave Records. He recorded 12 albums in the 60’s and 70’s that were released under this label, and, as touched on earlier in this conversation, all have recently been restored and reissued by Mack Avenue Records. What are some of the musical highlights of these recordings?

DM Well, that becomes a question of personal favorites, and my favorite is “Three O’Clock in the Morning” from A Night at the Movies. He plays a little stride on it, and it just moves along. I would like to take that with me to another life – it is just beautiful.

CS There was a lot of drama associated with the Columbia lawsuit, and Octave came out of that. When I think about Octave musically, I mostly think about what it stood for. It was more than just Erroll having his own label, it was an avenue for him to not worry about anything, which was very powerful and unusual for an artist at that time. Having Octave allowed him to record what he wanted, when he wanted, and without anyone telling him what to do. So, there is definitely more rawness in his playing on the Octave recordings than those on Columbia.

JJM Christian, what have you learned from the experience of working with the Erroll Garner Jazz Project?

CS Musically, I’ve learned a ton. For example, I’ve learned how to keep my left hand and right hand working independently, yet working together. How he is able to do that and be in two different places at the same time and create this tension – whether it is with his band or solo – is incredible to me. The way he plays is so impactful and influential because there’s so many devices that he uses, and so many things he can do. He has the ability to play any melody, and play it in a way that you can sing – even the introductions! It is all very melodic and all very sing-able.

He also has a great ability to reach and connect with people, so I challenge myself to do that without changing who I am. Erroll was performing during a time when music was changing dramatically, so I am interested in learning how he adapted to these changes while continuing to keep his backbone, his grounding, because throughout all these changes he is still swinging all the time. He’s even swinging on the Beatles tunes, and it’s really happening.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Erroll Garner play George Harrison’s song “Something,” from the 1972 Octave album Gemini

.

DM I’m glad you mentioned the Beatles because one of the last things I remember about seeing Erroll was while he was playing at Mr. Kelly’s in Chicago, which was a very nice little club, and he played the Beatles’ tune “Something” as a closer, and it was so beautifully performed. I will never forget that.

CS He had the ability to play anything. He would play a song like “Something” because it was a popular song the audience knew and would remember. That sort of idea affects my own performances and what I bring to my own band to record…

JJM As an example, the Blind Faith song “Can’t Find My Way Home” is on your latest album…

CS Yes. My mother always said that good music is good music, and it will always be good music. And Erroll Garner is good music, and he picks good music to play that also affects people and that becomes embedded in people’s lives.

JJM Beyond our discussion regarding Erroll Garner, what are you up to these days, Dan?

DM In these strange times with COVID going on, I have been confined to home, so I have been working on my autobiography, which is something I can do without having to go out and visit people. I am very lucky to have a great collaborator who is my editor and co-author, and is also able to help me with technology, which I am not very good at. He has a contraption that I talk into that then turns what I say into text. I am then able to edit it. We are far from finished but we’re making good progress.

I am also currently involved in a liner notes project for Mosaic Records. The seven-CD box is a label project, rather than an artist project.

JJM What is the label?

1947 Jack McVea phonograph record produced by the Black And White label

DM The label is called Black and White, which was active in the late 1940’s and early 50’s. Oddly enough the label started in New York and then it was sold to someone in California, so even though it had the same label name, after it moved to California it was like two entirely different labels. It is a fun project to work on.

JJM How many different artists?

DM Several different artists, including some rather obscure people, one of whom is Earle Spencer, who had a Stan Kenton-like big band in Los Angeles, although he disclaimed that influence. His band is pretty much forgotten – it doesn’t even appear in the jazz encyclopedias – but it is an interesting band with some good people in it, including the terrific trumpet player Al Killian, who worked with Ellington and Basie. He was a “high note guy” and a very good lead trumpeter later. Unfortunately he was murdered by a crazy landlord in LA for no reason at all, so he had a relatively short life.

Another player on this label is Arv Garrison, a guitarist who did some stuff with Charlie Parker, and who recorded on the Dial label. There is one piece called “Five Guitars in Flight” which has no less than five guitars, all playing in unison. So, there is some weird stuff, and some of it is more in the R&B vein. The stuff from New York is mostly traditional – there is Willie “the Lion” Smith, and there is Cliff Jackson with Sidney Bechet, and Art Hodes too, so there’s an interesting mixture. There is also one fascinating and practically unknown session that resulted in four sides led by Joe Marsala, with Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet and Cliff Jackson on piano.

JJM Christian, this has been an historic summer on so many levels, and I am wondering how the Black Lives Matter movement may be impacting your own art?

CS Being an African American, what we are going through – whether it has happened to you or someone you know – has been the story of Black life in America. There is a lot going on now, not only Black Lives Matter, but we also have COVID, high unemployment and lots of tension, all while people are stuck in their homes. The visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement is so important now, and at this moment because everyone’s attention is on the news of the day, people can’t hide from it anymore. We are all watching what is going on outside.

Christian Sands

I live in Connecticut and have been a part of these demonstrations, which have become very interesting. I have never seen people from so many different cultures come together in this way, marching and demonstrating for this cause. There’s definitely a lot of work to be done, but to see that these demonstrations are still going on, and that the fire is still there is remarkable.

Part of the worry that I have is that once the quarantining and COVID is over, do we go back to business as usual? Will we continue to fight? Will the point of the protests still be there? For me, it definitely will be. We need to have conversations about this and continue to fight and to be involved, to put pressure on local government. That is our story now, and it needs to continue.

My work is definitely a reflection of that, whether I am writing music about it, or talking with other musicians about it. Musicians have a platform to use, and it is my responsibility to do my homework and be informed about what is going on because people do look to musicians to help figure things out. My efforts now are to read, educate and to make sure that I am an example to others, just as musicians like Keyon Herrold, Etienne Charles, Jaleel Shaw, Marcus Strickland, Ben Williams and so many others are doing, fighting for rights.

This has become a world conversation. I am talking to artists in Paris and London and India who are all dealing with this issue, all very concerned and wanting to engage in dialogue about it, and who are demonstrating in their countries about it.

JJM Great music that endures to this day came out of the civil rights movement of the 50’s and 60’s, so it would make sense from a creative standpoint there is opportunity for artists like yourself to make your own moment here…

CS Definitely. I always tell younger musicians who are just figuring out how to play this music to write things down, to document how and what you are feeling, because your voice matters also. During this age of social media, people are connected and everyone has a level platform from which to speak. So, educate, learn, document, and press forward, because we younger musicians are doing the work of our generation now, just as you and Dan and others did the work during your time. We are continuing the work, which is essential in order to push forward and create change.

.

.

___

.

.

photo: Nico Van Der Stam

Erroll Garner at the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam in Nov. 1964

.

Garner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on June 15, 1921, and died of lung cancer on January 2, 1977

.

.

___

.

.

A sampling of music from Erroll Garner’s Octave Records albums, all recently remastered and rereleased by Mack Avenue Records

.

Garner performs “Someone to Watch Over Me,” from his 1964 Octave album Erroll Garner Plays Gershwin & Kern

.

.

.

Garner plays Lerner and Loewe’s “Almost Like Being in Love,” from the 1964 album Campus Concert

.

.

Garner plays Johnny Mandel’s “The Shadow of Your Smile,” from the 1967 album That’s My Kick

.

.

Garner plays “Cheek to Cheek,” from his 1968 album Up in Erroll’s Room

.

.

.

Garner plays Lennon and McCartney’s “Yesterday,” from his 1970 album Feeling is Believing

.

.

Garner plays Harry Warren’s “I Only Have Eyes For You,” from the 1974 album Magician

.

.

.

Two tracks from Christian Sands’ 2020 Mack Avenue Records album Be Water

.

“Be Water”

.

.

“Can’t Find My Way Home” (song by Steve Winwood/Blind Faith)

.

.

Click here to hear Christian Sands leading listeners on a song-by-song journey through side D of Erroll Garner’s midnight recording at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw

.

.

___

.

.

This telephone conversation took place on July 27, 2020, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita. Special thanks to Don Lucoff and Maureen McFadden of DL Media for their work in arranging this conversation

.

.

Click here to read our 2005 interview with Dan Morgenstern about his life in jazz

.

.

.