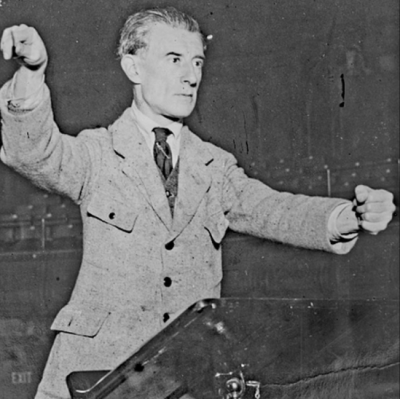

Gary Giddins

__________________________________

Village Voice writer Gary Giddins, who was prominently featured in Ken Burns’ documentary Jazz, and who is the country’s preeminent jazz critic, joins us in a conversation recorded on June 20, 2003 — and then slightly revised in October — about the profession of jazz criticism.

The conversation is an autobiographical look at the writer’s ascension in his field, and includes candid observations of other prominent critics. It concludes with a unique “Blindfold Test” that asks Giddins to name the jazz writer responsible for the essay excerpt he is spontaneously shown.

Conversation hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

*

“I don’t like the idea of trying to put a button on jazz, strictly defining the parameters, saying, ‘If you don’t do this you are not playing jazz.’ I don’t think it is true of any art form. I remember a writer in the Times saying once that not being able to define jazz was like not being able to define baroque. The guy was an idiot, because, of course, you can’t define baroque. Baroque is a very large category in which all kinds of aesthetic worlds co-mingle. That is also true of jazz, and I certainly don’t think somebody should be penalized for attempting to stretch the music in a different direction. When people try to stop the clock, they stop artistic pursuit, they limit the emotional response that we have to art. If stopping the clock is what gives them pleasure, fine, but I don’t think that’s good for the art, and it certainly has no appeal to me.”

– Gary Giddins

__________________________________

JJM What initiated your interest in criticism?

GG One of the first writers who got me excited was Dwight MacDonald, who wrote a movie column for Esquire in the sixties. In those days Esquire had a large format with a flat spine, and my father would keep them behind a hatbox in the closet — which at age eleven or twelve made me wonder what he was hiding. On a night when my parents were out, I started looking through them and found a letter to the editor from a woman complaining about MacDonald’s review of Ben Hur. She said she couldn’t understand why MacDonald complained about the various accents used by actors in the film, since she hadn’t noticed any actors; the film had transported her to ancient Rome. I thought that was hilarious, so I looked through the issues to find MacDonald’s Ben Hur review. Kids tend to be a shy in their opinions, especially about something touted as great or a classic. Ben Hur was a movie I found troubling for different reasons than MacDonald, but his prose, his detachment from the general commentary, his wit, his dissection of what was on the screen felt liberating to me. I had never read real criticism and it changed my way of thinking — a different way of looking at art and the world. Until then I had been accustomed to accepting the idea of a movie or book being great because it was prized and praised, but MacDonald encouraged me to step back and trust my own reactions, my own dissent. I read each issue of Esquire looking for MacDonald — and also found the Vargas drawings of half-naked women.

JJM So the experience of reading MacDonald made you want to explore criticism further?

GG More than that: It introduced the field, and inspired me to read the other Esquire reviewers. They had book reviews by Dorothy Parker and later Malcolm Muggeridge, who was similarly independent and acerbic. The classical music critic was Martin Mayer, and I often saved up to buy records he reviewed, including Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts, much of which I can still sing though I haven’t listened to it in years. Then I discovered Thomson to be a remarkable critic. Norman Mailer wrote a column called “Big Bite” that blathered about the bitch goddess and the Kennedy’s, and was interesting up to a point. Pretty soon I started reading seriously — Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Faulkner and Edmund Wilson all around the same time. I all but bathed in Wilson’s Classics and Commercials and The Shores of Light. And of course, Aldous Huxley, who greatly influenced my thinking and writing. Later Max Beerbohm and James Huneker, among many others.

JJM What other publications did you read?

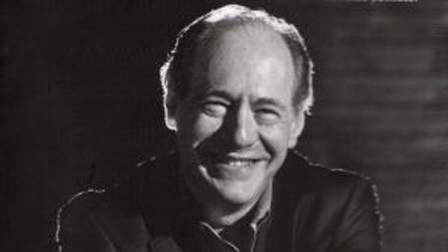

GG After discovering jazz at age fifteen, I was walking with my father down the street in Manhattan and saw a picture of Sonny Rollins on the cover of Downbeat, and asked him to buy it for me, at the then considerable price of thirty-five cents. Read it cover to cover. The record reviews were signed with the initials of the critics and I got to know them so well that I’d blindfold-test myself, covering the initials and guessing the author from the first graph or so. I always knew when the initials would be “D.M.” for Dan Morgenstern. I felt an emotional connection with him, because his writing stood apart from everyone else’s; it had so much warmth and authority and generosity. I’d buy almost any record Morgenstern recommended.

During this time I also read the Evergreen Review because I loved Samuel Beckett and many of the new writers they published. That’s where I first read Martin Williams, who had perfected a particular essayistic form of jazz crit, proving there could be a Wilsonian approach to jazz criticism — that it was a wide open field, a young field with much serious work to be done. I wrote about Martin’s work in Faces In the Crowd and an obituary appreciation of him will be included in my next book, Weather Bird.

I occasionally read the New Yorker and blindfold-tested myself with those writers, too, because at that time the magazine didn’t have a table of contents. So after a couple of paragraphs you’d know it was John O’Hara or Cheever or Perelman or, on one occasion, Salinger, when he published “Hapworth 16, 1924.” I think the first time I read Whitney Balliett was when they ran his long piece on Buddy Rich. I didn’t see Whitney’s stuff often at the time, and he didn’t influence me until later, maybe because his metaphorical approach initially put me off. It assumes a certain musical sophistication. Metaphors depend on one’s knowing both sides of the equation. If I write of “the wine-dark sea,” for that to have any meaning, the reader has to know what the sea looks like and what wine is. Comparing Pee Wee Russell to a mansard roof had a limited appeal for me, though later I became a huge admirer of Balliett’s writing. I loved Ira Gitler’s stuff– pithy, argumentative, full of puns and good feeling, and absolutely on the mark when it came to anything related to bop. I’ve learned a lot from him. But mostly it was Martin’s work that made me want to run out and listen to Jelly Roll with his essay in hand to see if I could hear things he wrote about. Same with Morgenstern’s liner notes, when he singled out the best eight bars I’d focus on them and try to understand what made them special. Criticism brought me deeper into jazz and jazz brought me deeper into criticism.

JJM When did you discover you wanted to be a writer?

GG I always wanted to be a writer. My first true hero was Nathanial Hawthorne. The House of the Seven Gables is one of the books I’d need on my desert island. It is the definitive treatment of the sins of the father and the weight of time. I reread it every few years, always with a new and different sense of astonishment, but also with nostalgia because it is a novel I read in fifth grade, inspired by the Classics Illustrated comic. It changed my feelings about writing and about books. I wanted to be the Hawthorne of my time, and was a long time in giving up that ambition. Before that, I read a lot young people’s biographies and soon identified more with the people telling the stories than their subjects. So I knew I was a writer. The question was, what kind? I figured I’d write literary reviews on the side while writing my own “House of the Seven Gables” or something. It never occurred to me that I had no talent for fiction, though reading V was a helluva wakeup call.

During my senior year in college, I wrote a short story for a fiction seminar. I greatly admired the professor, a fearful and wonderful man named M. M. Lieberman — that was his by-line. He wrote a collection of short stories that many years later I reviewed in the Village Voice. Mr. Lieberman was very tough and scared the hell out of a lot of people, but he was my kind of professor and I hung on his every word. My senior year was the year of Kent State, and Grinnell College, where I went to school, shut down its facilities in solidarity. No graduation — diplomas were mailed in the fall.

Everyone had to leave except those of us who lived off campus, which meant seniors and faculty. I still had to do oral comprehensives as an English major. I met with Mr. Lieberman at the student union over a cup of coffee. My three subjects were Eliot, Hemingway and Wilson —Eliot as poet and critic, Wilson as critic, and Hemingway as fiction writer. We talked for a few minutes, and Lieberman said I seemed to know the stuff pretty well, and changed the subject to writing in general. I had written a short story for him that he hated. I rewrote it but never heard from him about it. So I asked why, and he said, “Mr. Giddins, there really wasn’t anything to say. The story is worthless. If I were you, I would never write fiction again. Although, of course, if you are really serious about writing you won’t listen to a goddamn thing I say. But, I want to say something to you. You have a gift for criticism. You should pursue it.”

JJM Nothing like a positive comment from the professor to get the blood rushing…

GG Right. I didn’t give a damn about what he said about my fiction. It was just one of those moments — the kind of feedback I had never received before. When I told friends about Lieberman’s comment on my story, they looked at me as if I must have been heart-broken, but I said, “No, the guy told me I’m a critic.” And I believed him.

When I got out of school, that’s the direction I took, and was turned down by virtually every publication in the country, including the Voice. I got surprisingly unkind responses from Rolling Stone and Creem. I was a mess, but determined and strangely confident because I couldn’t do anything else. I was going to write and that was all there was to it. Eventually Dan Morgenstern at Downbeat gave me an assignment to review McCoy Tyner at a place called Slugs. Tyner used a deafening drummer, Alphonse Mouzon, and I couldn’t hear a thing — it was a dreadful set. I didn’t know what to do, because this was to be my first review. I loved McCoy Tyner, and didn’t feel comfortable criticizing him on the basis of one set. So I called Dan and told him I didn’t know how to deal with this. I asked him if I should go back and hear another set and he said he couldn’t get me comped again. I decided to wait for another assignment.

JJM And he gave you another shot?

GG Yes. Within a couple of weeks I wrote about Mingus’s return to the Vanguard — I think that was my first published jazz article other than liner notes — and a Jim Hall/Ron Carter set at Guitar. They both ran, and he gave me more stuff including records to review. Dan called me once and said he got a letter from Leonard Feather, asking who I was. That kind of interest from Leonard was unusual and for me it was amazing to realize I was being read by the guy who wrote the New Encyclopedia of Jazz, which I had virtually memorized.

JJM Your career also includes film criticism.

GG I suggested to Dan that I interview Nell King about her role as editor of Charles Mingus’s Beneath the Underdog. The day after the interview, she called me up to say that a friend of hers had become editor of the Hollywood Reporter and asked her if she wanted to review films. She said she didn’t want the job, but thought that it might interest me. I called the editor, Paul Sargeant Clark, who told me to send him three movie reviews; I went to see three movies that day and the next, sent him the reviews, and he hired me. I spent most of that year reviewing films, at $5.00 a review: fifty reviews for $250. I was working as a copy boy at a newspaper, so I wrote them during my lunch hour — a very useful apprenticeship.

I was doing occasional pieces for Downbeat at the same time, and after a year and a half of that, I felt I needed to choose between film and music. I thought if I did both, I would always be a dilettante, because you need to bury yourself in a subject, and I didn’t feel I could do justice to both. The decision didn’t require any real thought. For one thing, the Hollywood Reporter fired me and a couple of other people over my review of Lady Sings the Blues — Paramount had threatened to withdraw advertising. But I never felt my work as a film critic was in any way necessary. I was just another guy with an opinion. Film criticism would get along perfectly well without me.

JJM There are so many film critics, they are kind of like weathermen. There are three in every city.

GG There is that. But there were many film reviewers I respected, and I didn’t think my criticism added anything. In jazz, however, though I was a novice and there were obviously critics I admired, I was arrogant enough to think I had something to say that no one else was saying. Without something akin to that kind of arrogance, you can’t move forward. It’s arrogant to believe that anyone should read your prose, or look at your paintings, or listen to your music, or watch you act. You need a sense of certainty and in jazz I had that.

I loved jazz more than anything — well jazz and literature, which was doing all right without me — and I was delusional about what I could do for it. I was going to introduce jazz to my generation, rid it of stigma and mystery. I felt I could be a liaison between the rock and jazz worlds, even though I knew nothing about contemporary rock. I was out of my fucking mind. In any case, I put everything into jazz.

JJM Do you remember the circumstances around your first jazz record reviews?

GG While I was at the Post, I met an executive vice president of the New York Times. He asked if I would do a review on spec for the Times. I had gotten to know the record producer Don Schlitten, who gave me advance pressings of two records that would be issued months later — Art Tatum and Hot Lips Page after-hours sessions recorded by Jerry Newman in 1941. I suggested them, pointing out that no one else had them yet, and he said go ahead.

I sent him the review, and after some weeks went by, he told me that John Wilson wanted to review the albums and, as their jazz critic, he had precedence. I didn’t care about that; what I wanted to know was if the review was actually good enough that the Times would have run it. He was extremely supportive. Since I hadn’t kept a copy, I asked him to send it back, which he did.

JJM What did you do with it?

GG They came back to me at the Post, and I took them from the envelope and put them into another envelope addressed to Diane Fisher, the music editor at the Village Voice. I included a cover note saying the reviews were written for the Times and were in the Times style, where everyone is referred to as “Mr.,” but that it was an example of my writing and may I write for you?

A week later I was walking through the city desk, and Sylvianne Gold, a Post copy girl who subsequently won a George Jean Nathan award in theater criticism, not at the Post of course, said to me, “Congratulations, I just read your piece in the Voice.” I ran downstairs and got a copy, and there it was, not a word changed. To this day, it is probably the only Voice review that tagged everyone “Mr.” I asked Diane why she hadn’t called me before she published it, and she told me she liked it and just decided to put it in. I think I got $45. I asked her if I could write for her, and she said to come in and talk.

This was 1973, incense is burning in her office, and I think we sat on throw pillows. I told her I wanted to write a column, to which she derisively replied, “You don’t just get a column. You have to pay Voice dues.” But she invited me to contribute a Riff each week, and for the next year, I went out three or four times a week, wrote my ass off, dropping reviews in the Voice mail-slot every Sunday evening. There’d always be a dozen or so envelopes lying on the ground, visible through the glass door. I didn’t see Diane again for a year and had very little communication. There was no editing. If she didn’t like something, it didn’t run.

After eighteen months of that, the Voice changed ownership, and Diane knew that her time might be up, but she told me I had now paid Voice dues, and if she kept her job I’d get my column. A few days later I got a call from Robert Christgau. The only thing I knew about him was a column in Esquire, in which he expressed a loathing of Bill Evans and recent Miles. I figured the jig was up but he asked me to do the column and we hit it off right away, though at first I was shell-shocked about how much editing we did. Going from no editing to the best line-editor I’ve ever known was nothing if not confusing. I had not been edited at all in the Hollywood Reporter and only superficially in Downbeat, so I had the illusion I could write. Bob disabused me of that and taught me more than I can ever repay. The column ran every three weeks, and I’d do riffs for the other weeks. After a couple of years, I got to hating riffs. I was never comfortable with the length. I felt my strength lay in 1800 word essays where I could combine a general contemplation with obsessive detail. Eventually, I quit Riffs and settled on the bi-weekly column. April marked my thirtieth year at the Voice.

JJM Who are your other jazz criticism influences?

GG In addition to Dan and Martin, I have to add Albert Murray, both as a mentor and for his essays. I was lucky enough to count Al as a friend when I was young, and I can’t overstate his impact on my thinking and writing. He introduced me to Constance Rourke, Susanne Langer, John Kouwenhoven, and Thomas Mann’s incomparable Doctor Faustus. Albert was my graduate school. So those are the three main figures from the jazz world, in addition to Macdonald, Huxley, Wilson, Shaw, Huneker, and many others, including critics I abominated — like Pauline Kael — who in a way were just as influential for showing me what not to do, like spending half the review attacking colleagues and the other half establishing yourself as more important than the subject under review.

JJM How do you decide on what your next column is going to be?

GG Sometimes it’s obvious. A musician is in town whose very presence is a story. You can’t not review a major show or album release. In the beginning it’s so easy, because you have everyone to write about. After several years, by which time you’ve written many times about certain artists, the pickings grow leaner. Some artists are always inspiring — I could never grow tired of thinking and writing about Armstrong or Miles or Ellington or Rollins or Monk. But if I write an 1800-word essay on, say, Sam Rivers, it may be a good long while before I feel inspired to do another. On the other hand, I recently wrote a short piece about a terrific new album by the great bandleader-arranger Gerald Wilson. Then I went to see him at Birdland, and wished I could write the review all over again, because — good as the album is — the live performance was exhilarating and I had a much deeper understanding of what he was doing. Yet you can’t go back to the same well right away — I’m not sure why.

So you’re always looking for new subjects. I sample every disc that comes to my office — every disc, no matter what it is — and always blindfold-tested. One of the things my assistant Elora does is keep five new CD’s in the changer, and if something gets my ear, we put it into a “potential” pile. The stuff I don’t like at all we get rid of right away. There is a third pile — the “second chance” pile, where I need another listen before I know if I want to consider writing about it or not. That covers the CD’s, and then there’s the club scene. Is there a concert? Is someone playing whom I haven’t heard before? Is an established player doing something new? One thing you have to keep in mind is that I wrote essays, not short reviews, so the kind of record or concert I looked for were those that made me want to stretch out for a few choruses. I’m not comfortable with the new Voice policy of bite-size reviews.

In 1977, when I was writing a piece about Dizzy Gillespie’s sixtieth birthday, he told me that you would think trumpet playing gets easier as you go along, but it gets harder. I asked him if he was referring to his embouchure, but he said it had nothing to do with technique; it becomes harder because after you’ve played certain ideas and have exhausted them, you have to find new things. That’s the way it is with writing. You exhaust phrases, you exhaust ideas, you don’t want to keep repeating yourself, so it becomes harder in that sense, but easier in the purely technical sense.

JJM Is it hard to not become cynical about your work?

GG It is easy to become cynical about your own work. Does it have any value? Does anyone respond to it? But I’ve never become cynical about the magic of music itself. That keeps me going. You have to distinguish between musicians and the people who package the musicians. I’ve never been cynical about jazz and the artists who play it. I’ve never been anything but cynical about the record industry, which with few exceptions is an appalling enterprise. I root for the downloaders — they have a greater love of music than its corporate gatekeepers.

In the ’70s, I got to know Helen Humes, who sang at the Cookery. One night she saw me walk in and waved me over to her table. I sat down, she opened her purse, bubbling with enthusiasm, and told me she had something incredible to show me — it was a check for about $24 in royalties, sent by Don Schlitten, who had put out “Midnight in Minton’s” with Don Byas, on which Helen had a couple of vocals. She told me she had been recording since she was thirteen years old, sang with Count Basie, had big rhythm and blues hits in the forties, and yet this was the first royalty check she had ever received. She said she wasn’t going to cash it, she was going to put it up on her wall. That says a lot about the record business.

JJM Martin Williams wrote, “We have a favorite pastime in jazz — we musicians, reviewers, historians, journalists, fans. When we get together in almost any combination, the conversation will sooner or later turn to laments that jazz is not understood, does not have the respect, the prestige, the support that the music has rightfully earned and that our symphonies and opera companies have.” How important is it to a critic that jazz be respected or “understood?”

GG I remember the period when a statement like that would have been true. It is certainly not true now. Maybe we have become, not cynical, but too accepting of the situation. We know jazz is going to be passed over by the Pulitzer and trivialized by the Grammy, and so forth. In other ways, jazz is too respected. Now conversations are usually about whether anyone is excited about a new recording or recent performance, and who’s new on the scene. The question about prestige is an old one, and I think it has largely disappeared.

JJM Many of us are attracted to jazz not only because the music reaches us, but also because it resides outside the mainstream culture. Isn’t that part of the appeal and would we be as excited about the music if it were a more integral part of the popular culture?

GG I don’t know. I don’t agree with that. There are certain recordings I listen to that still amaze me because no one knows about them. When I listen to a Count Basie record, and my heart is fluttering along with Lester Young, I catch myself thinking that maybe two percent of the nation’s population knows this music. Yet it was popular in its day, and I have no doubt that if it had more exposure, it would find a level of popularity in our day as well.

I will tell you something that jazz critics used to talk about all the time. “How did you get into it?” In no other field do people say that. “How did you get into books?” or “How did you get into film?” How could you not get into them? But in order to appreciate jazz, most of us had to step outside the boundaries of our regular lives, because it is not readily available. It is not a question of whether it becomes a popular music. The question is whether it is allowed to reach its potential. One thing we learned from the Ken Burns series is that people all over the country watched it. They got involved with some of the stories and artists. Jazz record sales doubled in February of that year and declined when the show finished. I was on a book tour immediately after the Burns program aired, and every place I went, people would want to tell me about their experiences with jazz. A guy in Chicago told me, with astonishment, that his fourteen-year-old daughter came home from Tower Records with two CD’s — Britney Spears and Louis Armstrong. So, even kids were responding. You just have to assume that if the music were available on radio and television, and not just as homework in survey classes, that a lot more people would awaken to its pleasures.

People forget that in the early and mid sixties there were many jazz hits. There was “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” “Desifinado,” “The Sidewinder,” “Hello Dolly,” “Take Five,” “Hang on Sloopy,” “The In Crowd,” and others. There was a real window for jazz producers to take advantage. Few of them did.

JJM In the introduction to Visions of Jazz, you wrote, “A jazz classicism that can keep alive the music of Ellington and Basie and Lunceford and Gil Evans, yet fails to coexist with the most vital of jazz traditions — its inventiveness, irreverence, and canny involvement with other musics and life as we live it — will produce a dozen lovely plaster busts for home or school and a gorgeously ornate headstone.” Does the past become so mythologized that the present holds little luster with critics and fans?

GG The jazz audience is generational. People like the music that aroused their interest when they were young. They don’t necessarily follow it into the next period. At the JVC Festival recently, there was a Bix Beiderbecke concert, and some guy told me that this was the best jazz band he had heard in forty years. I couldn’t even respond to that. Clearly he only wanted to hear this kind of music. There are a lot of people like that. I have met people over the years for whom jazz ended with Bird or Stan Getz or Ellington. Critics are often generalists who try to follow the entire development of the music. Most listeners do not. In downtown New York, the avant-garde fans pay lip service to the earlier players — they know and love some of them — but that is not where their focus is. People who listen to traditional jazz basically ignore what the avant-garde does. That’s the way it’s always been and always will be. Most people who buy subscriptions to Mostly Mozart do not support The Kitchen.

There is a mainstream sound now that can be characterized as a “post-Miles Davis sound,” and when concerts feature musicians who came up in the generation of Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea and the Breckers, an audience is there for them. For many people jazz begins with Miles. I recently received the souvenir book for the Playboy Jazz Festival, and would you believe there was not one Louis Armstrong performance among their list of the twenty-five essential jazz recordings? That’s insane.

JJM Do people concern themselves too much with trying to define what is and isn’t jazz?

GG I don’t like the idea of trying to put a button on jazz, strictly defining the parameters, saying, “If you don’t do this you are not playing jazz.” I don’t think it is true of any art form. I remember a writer in the Times saying once that not being able to define jazz was like not being able to define baroque. The guy was an idiot, because, of course, you can’t define baroque. Baroque is a very large category in which all kinds of aesthetic worlds co-mingle. That is also true of jazz, and I certainly don’t think somebody should be penalized for attempting to stretch the music in a different direction. When people try to stop the clock, they stop artistic pursuit, they limit the emotional response that we have to art. If stopping the clock is what gives them pleasure, fine, but I don’t think that’s good for the art, and it certainly has no appeal to me.

JJM In addressing that, you wrote, “Spoilsports emerge who want to establish more exclusive laws of jazz immigration. Unlike Ellington, who reveled in diversity and abhorred restrictions, the guardians of musical morality are appalled by such latitude, and mean to cleanse jazz of impurities transmitted through contact with the European classics, American pop, new music, and other mongrel breeds.”

GG Well, Ellington was attacked for “Reminiscing in Tempo” for the same reasons that musicians are being attacked now, whether it is Dave Douglas for playing Balkan rhythms or Don Byron for mixing classical and jazz. In a sense, that is the obligation of the artist, to play what he knows. That’s an old literary cliché. What do you write about? You write about what you know. You play what you know. You paint what you know. You give free reign to your imagination. No artist abides by a rulebook. Why would critics want to imagine that a rulebook could or should exist? It never has, it never will.

JJM What do you make of Stanley Crouch’s argument that there is an attempt by certain critics to downplay jazz music’s African American heritage and stretch the jazz idiom to include more white, European in-fluenced musical explorations?

GG There may be, I don’t know. If he is upset because there are a few writers writing like that, then I agree with him — there are fools in every idiom. I don’t know a serious jazz critic who would want to argue that jazz is not at its base an African American form. At the same time, we also know that there have been great white players from the very beginning, and that there have been great players in Europe from almost the very beginning. If it was just a black music it would be a folk music and it would have had no more international impact than bluegrass. But jazz is an international art. It is bigger than any one artist or any one people or any one nation. Nevertheless, we all know where it comes from. We know that most of its great artists have been black and continue to be black, but I think you want to be very careful about how far you go with that. I don’t think you want to sit in the theater and say, “Well, I don’t know, can Bill Charlap really play?” I know Stanley would never say something like that.

It seems to me that the great white players are the ones who don’t imitate their black idols. For example, Stan Getz was not an interesting player when he was just playing Dexter Gordon and Lester Young licks. It is when he discovered who he was and started playing himself that he became a truly great jazz musician. To achieve anything of value you have to show who you are. Louis Armstrong said that jazz is what you are. The saxophonist Brew Moore once said that if you don’t play like Lester Young, you are playing wrong. That is why most of the people reading this conversation never heard of Moore — a very good tenor player if you want to hear somebody playing Lester Young riffs. But he never went much further than that. The great players play who they are, where they come from, what they know.

The foundation of the music, in terms of swing, timbre, blue notes, harmonies, melodies, riffs, call-and-response — well, we know where that comes from. It comes from the church, created in America by Negroes. As Art Blakey never tired of saying, it did not come from Africa. There are elements that come from Africa but the genius of Louis Armstrong is American — it may be America’s saving grace. It certainly did not come from Europe, even though he uses a European system of harmony. At this point, after one hundred years, if people in Europe decide that instead of wanting to learn the music of Bach, Beethoven and Mozart, their real gods are Ellington, Armstrong and Parker, who will complain about that? Let them work in that idiom. If they produce something good, cool. If not, then, good try. What else is there to say?

JJM The critic Martha Bayles said in a recent Jerry Jazz Musician conversation on jazz criticism that art evolves, and its evolution doesn’t mean that the next generation’s art is going to be better than that of the previous generation, it just means it is going to be different.

GG Yes, and that is what critics do. Critics chronicle and evaluate the music as it comes to them. That is pretty much the limit of what we do. I don’t think that at our best we are proselytizers waging arguments about who is legitimate and who isn’t. Everybody has to be taken on their own speed. I have often said, and I think I said this to you in our conversation about Cecil Taylor, that if Taylor had been white and had come out of a different background, he might have been playing to a different audience.

JJM Yes, and he would have been recording for Deutsche Gramophone.

GG Exactly. For whatever reason, Taylor came into my life; I was pursuing jazz and I stumbled across him and I am grateful I did. Now, if you want to argue that on some level it is not jazz, I would be happy to debate you on that subject. But I don’t really give a shit. As I’ve said before, you can call it whatever you want. All I know is that his music fills me with joy, and so does Bud Powell’s and Fats Waller’s. I am glad that they exist.

The name “jazz” simply cannot contain all the music that exists under the umbrella — and that is a tribute to jazz, a tribute to the African American achievement, a tribute to a music that has survived for over one hundred years without much support from the establishment, without a majority audience. Yet it continues to attract young musicians of great talent. I am sure Jason Moran could find a lot of ways to make bigger bucks, going on tour as many of his predecessors did, supporting pop and soul groups. Instead, he comes to New York to contribute something to this great tradition. In every generation we get those kinds of artists. The other night, with Gerald Wilson, I heard a gifted young trumpet player named Sean Jones. I guarantee you will be hearing a lot from him. Thank God for these guys.

JJM Francis Davis writes in “Advertisements for Myself,” the introduction to his collection of essays called Like Young, “I admit to addressing my fellow critics as well as potential record buyers.” Do you ever find yourself addressing your fellow critics in addition to your audience?

GG I don’t. I never do. Unless I am taking on another critic, which I try not to do unless I read something that really really pisses me off. When I go into the alternative universe of writing, the person I mostly write for is me. I am writing in part to the kind of fan I was when I was sixteen or seventeen, reading jazz criticism. I’m writing the kind of work that I like to read, writing to explain to myself what I’m hearing and thinking.

I was a substitute movie critic for Jim Hoberman in 1990, and during that time I discovered that even though I was writing the same amount of words every week, I was doing it in half the time. One reason is that so much of film writing is concrete — that is, it deals with plot and material that you have to put in about the acting, photography, and so forth. There is far less of that when you write about music. So much of it is abstract. You are looking for concrete terms to describe the ineffable, especially when, like me, you can’t rely on the specifics of musicology. There are times when I would love to be able to explain why a particular chord moves me, or write about the way a sixth chord works in a certain context, or understand a particular cycle of harmonies. I don’t know any of that stuff so I am forced to rely on more traditional literary means. Writing to other critics doesn’t interest me at all. What am I going to tell a Francis Davis or a Dan Morgenstern or Stanley Crouch? I’d be scared to death if every time I started typing I imagined them looking over my shoulder.

JJM Not being a musician, I have often had trouble maintaining an interest in a musical biography where the music is discussed in detail.

GG I love that stuff, actually. I enjoy putting on records and then reading the musical transcriptions. That’s great fun. As a critic, I have been very grateful to Gunther Schuller for his Early Jazz transcriptions. I function in a different world, as most critics do. If you are writing in a popular journal for a mainstream audience, you can’t do musicology — even if you have the ability. Something else I have discovered over the years is that people who have that ability very often don’t have ears. I was so intimidated once, meeting a music professor after I did a lecture at his university, and then he told me that the greatest trombonist who ever lived was Bart Varsalona. This guy could listen to a J.J. Johnson or Jack Teagarden solo and write it right out, but not necessarily feel it. It’s a separate talent.

JJM Before we get to the “Blindfold Test,” I know you want to say something about the state of the art of jazz criticism.

GG Yes. I often read people complaining about how bad the state of jazz criticism is. There was an article in The Nation about how low the level is. Yet no school of criticism from my generation — the baby boomer generation — has shown more talent than the jazz guys. Not in film, literature, dance, or classical music criticism can you find as many solid and devoted critics as Stanley Crouch, Bob Blumenthal, J.R. Taylor when he was writing, Don Heckman, Francis Davis, Scott DeVeaux, Peter Keepnews, Larry Kart, Will Friedwald, John Litweiler, Gene Santoro, John Corbett, Gene Seymour, Kelvyn Williams, Steve Futterman, Ben Ratliff, Ted Gioia, Bill Milkowski, Howard Mandel, Eugene Holley, Bill Kirchner, Ashley Kahn, Fred Kaplan, Ted Pankin, Lewis Porter, John Szwed, and others. There are so many critics out there who have their own voices. The field of jazz criticism is very much alive, and a lot of important work has been done over the past thirty years. When I was growing up, jazz biography was almost unheard of. The few that existed were crap — they read like ersatz novels. Now there is an upsurge is real scholarship. Are there idiots out there too? That goes without saying. But on balance, I’d be very proud to be counted among those I’ve mentioned.

JJM We are living in the days where everyone can be a critic. “Do it yourself” reviews are available on Amazon.com and on many popular web sites, jazz sites included. How do you feel about that?

GG There used to be a magazine that did that. I think it was called Different Drummer. It was inexpensive looking, all white with black print, and very little art work as I recall — all amateur stuff. I hated it! Criticism isn’t an amateur pursuit, it’s a serious craft, sometimes raised to an art. Don’t get me wrong, I’m very interested in opinions — I get letters all the time from readers who know a lot more than I do — but criticism goes beyond opinion. It’s a literary, not a musical pursuit, and something you have to work at.

You know, a Stanley Crouch may say something you think is preposterous, but he has earned the right to say it, if for no other reason than because he has lived his whole life inside this music. He has spent more time in clubs than almost anybody else I know. If this is a conclusion that he comes to, he has the right to say it, and you have to give him respect even as you disagree. I don’t feel that way about some guy who owns eleven records and once went to a show at the Village Vanguard. I am just not that interested.

One difference between professional and amateur critics is that amateurs almost always prefer to write about themselves — “the first time I heard this record” kind of thing. Jesus, sometimes I’m tempted to do it myself, and I go a little overboard in that direction in the intro to my next book. Maybe it’s a consequence of getting older. But you do try to keep a lid on it; when a writer begins to see the artists he writes about as supporting characters in his own life, he’s in trouble. Perception outweighs memory.