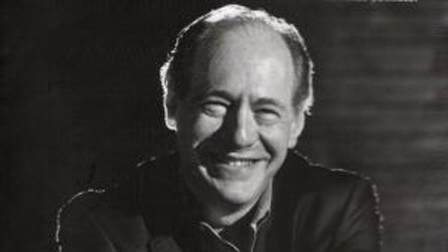

Gary Giddins

____________________

In the final column of his thirty year career as jazz critic of the Village Voice, Gary Giddins wrote, “I’m as besotted with jazz as ever, and expect to write about it till last call, albeit in other formats. Indeed, much in the way being hanged is said to focus the mind, this finale has made me conscious of the columns I never wrote.”

He went on to lament about not having written columns on the likes of Booker Ervin, Charlie Rouse, George Coleman and other musicians most easily categorized as “underrated.”

His farewell column inspired us to believe “Conversations with Gary Giddins” on Jerry Jazz Musician would be a great opportunity for Giddins to talk about those left behind. This May 10, 2005 conversation — the fourth and last in the “underrated” series — is devoted to big bands. While the “underrated” theme is a topic of the discussion, Giddins covers a lot of ground, including his thoughts on many of the prominent musicians who have left their mark on big band music and beyond.

I have long wanted to let Jerry Jazz Musician readers know that having a conversation with Giddins — particularly about a topic he is so passionate about — is a provocative, educational, often hilarious, and unbelievably invigorating experience. Everyone who loves the history of jazz should be so lucky to have the opportunity of talking with him for an hour…I am privileged to have had about a dozen of them now.

JJM

Conversation hosted by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

*

Weatherbird: Jazz at the Dawn of its Second Century is the new collection of 140 pieces Giddins wrote over a fourteen year period, and is the companion volume to Visions of Jazz, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. In a recent Jerry Jazz Musician book review, Paul Morris writes of Weatherbird‘s riches, a review that includes a variety of book excerpts and sound samples.

______________________

“When you went to see Ellington, it wasn’t just him you were going to see; there were a dozen legendary figures in it, among the greatest musicians in the world. By the second or third number of the concert, I was so mesmerized by the band that I started walking toward the bandstand. When I got to the lip of the stage, there were a half dozen other people beside me, all of us with our jaws hanging right in front of the reed section. When those five musicians played together in unison, you could hear the cumulative sounds of the five saxophonists and clarinetists blending perfectly, almost like an organ chord. But at the same time you could also hear each individual voice in the blend. You could always hear Hodges, you could always hear Gonsalves, you could always hear Carney. That just blew my mind, to hear five completely unique and distinct individuals who could blend and be distinct at the same time. That was part of the excitement. Then there was the whole way he manipulated the band. On some pieces he would start out with long piano vamps, and you didn’t know where it was going. Each solo was set up like a beautiful little portrait in the middle of something, and then he would have background riffs for the soloists that were so lively and would seem so spontaneous — it was as though the band were improvising a duet with the soloists.”

– Gary Giddins

*

____________________

JJM The big band era was one of the most important periods in the history of music. Both of us are too young to have participated in the era’s golden age — the swing era of the thirties and forties. What I imagine about the big band era is that it was filled with style, romance and elegance the likes of which I haven’t seen in my lifetime. What comes to your mind about this era?

GG That’s all true about style and romance. You can’t separate the swing era from dance because the public was so involved with it. I tend to think that there were two big band eras; the first was the dance era of the thirties and early forties, and the second followed in the fifties, when there was a tremendous revival of interest by jazz composers in writing for large groups, led by a new generation of exciting arrangers and composers like Thad Jones, Gil Evans, Bill Holman, Gerry Mulligan, Ernie Wilkins, Frank Foster, Sun Ra. The difference was that, unlike the first swing era, when music was performed primarily for dancers, theirs was a concert music featuring a larger group instead of a small group. Another great period began in the mid-sixties when Thad and Mel created the Monday night band at the Village Vanguard, leading to a whole slew of Monday night — or musicians’ night off — bands at various clubs in the seventies and eighties. That, in turn, led to the retro movement, which I found musically unlistenable, for the most part, but which also encouraged a revival of jazz repertory orchestras.

Today, a jazz big band can barely function commercially. It needs some kind of support. The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, for example, is dependent on donations. But the Swing Era of, say, 1935-1947, was a period when organizations with fifteen to seventeen pieces, plus singers and arrangers, traveled the entire country, going to virtually every city of every size, playing in any kind of large ballroom, and people were coming out for them. It was a magical period. When we think of the big band era now, we think of the great bands that survived because they had enduring musical interest, and most of them were successful. Count Basie was a huge star, Duke Ellington’s records sold enormously well, as did Benny Goodman’s and Artie Shaw’s and others, but many people who actually lived in that era admired bands we don’t talk about, like Guy Lombardo, Hal Kemp, Sammy Kaye, and Kay Kyser. Kyser was so popular he became a minor movie star, yet he couldn’t play an instrument and got by chiefly on banal novelties.

Many bandleaders then were showmen — front men for orchestras. The point is that these bands — whether they were swing bands or sweet bands, hot or corny — provided dance music that had the whole country jumping in a way that it is hard to imagine now. And, because their music inspired the kind of dancing where people hold on to one another, there was a tremendous amount of romance attached to it. I’m not much of a dancer, but I danced to Ellington and Basie, among others, and there was nothing else like it — dancing to Basie’s band when it played the Palladium was euphoria. My wife and I had just met and we still talk about it.

JJM People who lived during this time always light up when I bring up the swing era of the thirties. Sure, that may have something to do with the fact it was the time of their youth, but there is no denying the dance band culture was one of elegance and romance.

GG Yes, it was such a different social era. People went to meet each other to dance, which inspired competitiveness concerning how well they danced and how elegant they were and how they dressed. When you went out, it was a night out to shine, to show yourself off. Martin Scorsese captures some of that feeling in the long opening scene of New York, New York. There was also the dark side, of course, like marathon dances that Horace McCoy wrote about in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, which was made into a pretty good film; they were horrific, grueling spectacles almost medieval in their cruelty. Anita O’Day once told me about participating in a marathon. But for the most part, when you went out to a dance, you wanted to look your best, to have a good time, and when the band wasn’t playing, you could hear yourself think. There was silence, moments for conversation. When the band played something incredible, people stopped dancing, the music fans anyway, and hugged the bandstand to watch the musicians. John Lewis said that by 1940, Ellington was so daring that people were afraid to dance to his band, for fear of missing something. Yet people never stopped dancing to his band, till the very end. Most great bandleaders were showmen. Jimmie Lunceford’s band was one of the great dance bands, but it was also the greatest of show bands. People who witnessed that band never forgot its musical precision, the way the players looked and the kinds of tricks they would do, like throwing their instruments up in the air. A lot of things went into it.

JJM Big band leaders also had to act as talent scouts. Who were the great talent scouts among the big band leaders?

GG There was such a tremendous pool of musicians, and each band had its own avenues of recruiting. Some bandleaders did most of it themselves, but others assigned it to managers and straw bosses, or relied on recommendations from musicians and colleagues. Some of them didn’t want to put themselves in a position where they had to hire and fire. Ellington was famously disinclined to fire anybody. In the instance of Ray Nance, someone told Duke there was a guy in Chicago he should hear, and as there was an opening in the band, he went to hear him, liked what he heard, and hired him. Paul Whiteman hired Bing Crosby as the first solo vocalist ever to tour with a band on the recommendation of two members of the band who had seen Crosby’s vaudeville act — Whiteman hadn’t even heard him. I interviewed Count Basie and Woody Herman about this subject, and both said that when a musician left the band, it was his responsibility to recommend somebody for his seat.

JJM Interesting …

GG One of the reasons that a lot of the bands remained black or white after the war is because when a black musician left a band that was primarily black, he was likely going to recommend a friend. The musicians he grew up with and hung out with were probably black, and the same thing would be true of white players in largely white bands. So although Basie began to hire white guys, it remained a predominantly black band, just as Woody’s band remained mostly white. Herman’s band had a tradition where the departing player had to recommend a new musician to audition. That’s how chairs turned over.

JJM While revisiting some information in preparation for this interview, I was reminded about some of the great talent in these big bands, especially early on. Go down the list of the players in Fletcher Henderson’s band, for instance — Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Don Redman, Benny Carter, Cootie Williams — and this is early in the era when many of the players didn’t really have reputations

GG Yes and some raiding did take place. It wasn’t considered a nice thing to do, but the most famous example of that would be Goodman raiding Duke for Cootie Williams and apparently also trying for Johnny Hodges. Duke gave him his blessing about Cootie, remarking that he would be back, and he was — twenty years later. It was a big event when Cootie left. The composer Raymond Scott memorialized the occasions with his “When Cootie Left the Duke.” Until 1940 everything was so segregated that white bands only raided white guys, so when Goodman wanted Cootie, it was really something, not only because he was poaching a soloist closely associated with the Ellington sound, but also because he crossed the racial divide.

JJM Paul Whiteman raided Jean Goldkette’s band, no?

GG Well, he waited until the Goldkette band was falling apart. When he originally went to see them in Atlantic City, he told them that he didn’t believe in raiding, and had no interest in destroying the band, but if they found themselves without a band, he would be interested in hiring them. Eventually they went with him.

JJM Were big band arrangers more advanced and sophisticated in their thinking than the soloists they wrote for?

GG I don’t know if they were more advanced, but I think that they had an unusual technical ability because they could think in terms of notating ideas the soloists were playing and expand them into formal musical works. Many arrangers were basically taking what the soloists were doing and using those ideas as the basis of their orchestrations. One of the things that make Benny Carter’s famous reed section episodes so exciting is that they sound like a Benny Carter solo. And Don Redman famously said that after he heard Louis Armstrong play, he changed his entire style of arranging. The Basie band grew organically out of the nature of his rhythm section and the kind of soloists he employed — especially Lester Young. Once arrangers get to know the band’s stylists, they write arrangements or compositions for them. Ellington, for example, was the composer for his own orchestra, and if he assigned things to other people they were going to write in the Ellington style. On the other hand, a band like Woody Herman’s succeeded because it reflected the styles of so many great writers he brought in over the years, and the band constantly changed because of it. It went from being a dance band to a blues band to a bebop band and eventually a concert orchestra. Woody didn’t like playing for dancers, at least in the later years. He told me once that Glenn Miller told him he hated “those motherfucking dancers,” which we both thought was pretty ironic.

JJM Herman was famous for keeping up with the times, and for altering his band to meet the changes.

GG Yes, he got a very negative review once in the New York Times from John Wilson, who hated the electric piano Woody used in the seventies. After the review appeared, Woody ran into John at the Half Note in midtown Manhattan, and he really accosted him, insisting that Wilson could afford to be behind the times, but that he –Woody — couldn’t. He had to concern himself with appealing to audiences by giving them what they want to hear while also staying on the cutting edge of the music. Everything he said made perfect sense. When the electric piano fad faded, it disappeared from his band as well.

Woody had a powerful sense of integrity. He discovered a trombonist, Jimmy Pugh, who was a tremendously skillful player. After a few years in Woody’s band, he left to do studio work, where he made a good living performing jingles and that kind of thing. Woody was furious. He didn’t feel you get into a band of his quality to end up playing jingles — to him it was about the art, and if you have talent you don’t waste it on selling toothpaste. So the guys who played in that band were very loyal to him because he loved the musicians and he loved the music. It was the same with Basie. Basie ruled without hardly saying a word — he did it all from the piano. He had a straw boss, saxophonist Bobby Plater, who would rehearse the orchestra, and when they got the arrangements letter-perfect, Basie came in and the arrangement would change completely just by the nature of the way his piano altered the rhythm section. At times, if he found passages were cluttered, he showed himself to be a canny editor, cutting stuff until a piece had economy and space to breathe.

JJM Who were some of the underrated big bands?

GG When you talk about underrated, you have to distinguish between bands that may not have received attention during their era but should have, and those that were popular then but are neglected now. Lucky Millinder’s band, for instance, was influential in its day but never quite broke through at the time because it was playing the kind of jazz/r&b that Lionel Hampton owned. I’m more concerned with bands that may have been large in their day but are now forgotten. I am amazed at how many jazz fans and critics don’t really know Jimmie Lunceford, one of the central figures of the Swing Era. Gunther Schuller thinks his was one of the three most important concepts of orchestral jazz. Sy Oliver was the primary arranger, but Eddie Durham and Eddie Wilcox and others arranged as well. Gerald Wilson played trumpet in Lunceford’s band, and got his start writing for him. Lunceford’s band had an incredible sparkle to it, and the records can knock your socks off. It is hard to believe the things they did, the precision, the irony, the maneuvering between the sentimental and the ultra-hip.

There have been many attempts to recapture the sound of the band — Billy May did one, and of course the American Jazz Orchestra took a shot that I’m very proud of. But Lunceford is ultimately untouchable. The way Oliver’s writing and the Jimmy Crawford rhythm section implied a two beat rhythm even though they were basically playing four gave it a unique bounce. They incorporated popular songs that most other bands wouldn’t dare touch, like “Annie Laurie,” a folk song from the nineteenth century and one of Lunceford’s very best recordings, a masterpiece without a wasted note —every soloist scores, especially Trummy Young. I’d put that on the short list of great big band recordings. Then there’s corny material like “On The Beach At Bali-Bali,” which they turned into something at once coy and passionate, or even “The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down.” One of Lunceford’s great recordings is Sy Oliver’s ingenious arrangement of “Organ Grinder’s Swing,” where every eight bars has a different combination of instruments, so it is constantly shifting and changing, yet it has a smooth, delicate, beautifully engaged sense of swing. I don’t know why people don’t get the Lunceford band. Chick Webb’s band is one that doesn’t get as much attention as it should. And Any Kirk’s — the Mary Lou Williams arrangement of her piece “Walkin’ and Swingin'” is flawless.

Because some of the white bands made a lot of pop records, people forget what great jazz orchestras they were, Tommy Dorsey’s chief among them. He hired Sy Oliver away from Lunceford, and had many great players, yet most people think of the Dorsey band as the one in which Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford sang. It had much more than them — Buddy Rich and Joey Bushkin were in the rhythm section, Bunny Berigan played in the orchestra for a while, and Tommy’s trombone sound gave it a special feeling, dark and contemplative. Artie Shaw’s band was terrific. One of the reasons I don’t think he gets the attention he deserves is because it has been fifty years since he was a functioning musician, but with his passing I expect there will be a rediscovery. There has to be, because no one sounded quite like Artie Shaw — the drama and calculation and, when he was really on top, elation. Shaw had his own style of organizing bands, using strings and singers. He was a complete individualist, hiring arrangers of varied backgrounds, taking all kinds of chances, and never feeling compelled to play in the particular style of a particular period.

JJM You mentioned Bunny Berigan. Is his role in the swing era truly appreciated?

GG Probably not, because he died so young. Berigan was a great trumpet player who had an unusual career. He made one of the most durable hit records in jazz history, “I Can’t Get Started,” which he actually recorded twice, once for Columbia, and the longer hit version, for Victor. It was a very simple idea — the orchestra played dramatic chords to count off the measures, and Berigan played trumpet phrases based on those chords, jumping away from them and building to a climax. He then sings a chorus, followed by a similar trumpet chorus even more exciting than the first. It was a long record, over four minutes, and at one point was released on two sides. Which may be why a BMG compilation came out a few years ago including only the first half; BMG is a company that frequently does things that seem to have no purpose other than to assure consumers that it really is run by idiots. I don’t think the whole performance is in print as we speak.

Yet this recording was on jukeboxes all over the country well into the seventies. There were bars in New York not long ago that had rock golden oldies on their jukeboxes, as well as Bunny Berigan’s “I Can’t Get Started.” But for some reason, even though that arrangement was an ideal format for him, he never made another record like it. I am a big fan of Berigan’s, and I think that his band made quite a few good records — I like his version of “Caravan” very much, “The Lady From Fifth Avenue,” “Turn on that Red Hot Heat,” “Mahogany Hall Stomp,” “Mama I Wanna Make Rhythm,” and the incomparable “All Dark People Are Light On Their Feet,” which is about dancing, not sexual orientation. I find his Bix adaptations a bit wearying, but he is due for a serious anthology. He didn’t have the hippest arrangers and at times he gave too much face to other players. He was a serious drinker, and so a better sideman than bandleader, which could also be said for Jack Teagarden. But Berigan was there when Goodman was putting together his band, and when Tommy Dorsey was putting together his band, and he usually delivered.

JJM Would you consider Benny Carter an underrated big band leader?

GG Oh man, his band was the most underrated of the forties. He could never afford to successfully keep a band, which was a great source of disappointment to him. But he wasn’t interested in only having a dance band, and some of his music was just a little too sophisticated for most people. So even though he had a roster of musicians that included J. J. Johnson, Max Roach, and Miles Davis, among others, and so innovative in his use of singers, the band never really had a success. The closest he ever had to a hit was a song he co-wrote called “Cow Cow Boogie,” which Ella Mae Morse recorded, but not with his band. I think he did have a minor hit with a Savannah Churchill vocal — I can’t recall the title and doubt if I heard it. His recording of “More Than You Know,” featuring Benny’s trumpet and Leroy Felton’s bass-baritone vocal is another one for the shortlist.

Another underrated leader like that is Red Norvo. His band had three things going for it that should have put it over the top: Red’s xylophone, Mildred Bailey’s vocals, and Eddie Sauter’s arrangements. While Mildred was one of the great big band singers of all time — she was the first woman ever to tour permanently with a big band while when she joined with Whiteman’s orchestra — Sauter’s music was too subtle for many people. The band didn’t swing hard enough, preferring big, cloudy harmonies, the kind that to some degree are associated with Claude Thornhill and Gil Evans in later years So, while Norvo made a lot of great records like “Remember,” he never went over that big with the public.

Getting back to Carter, I love how his arrangements swing so naturally. There is such a sense of spontaneity in his writing. Somebody once said that nobody can write for a reed section quite like Benny, and I think he and Ellington are the two who really knew how to make unison saxophones charge. Maybe his band, and Norvo’s too, was too introverted to make it with the general public. He spent the peak years of the swing era in Europe, where his influence was decisive. That recording session he did with Django and Hawkins in 1937 is about as good as it gets. Hawk’s work on “Out of Nowhere” is one of the great tenor solos.

JJM My own experience with him is ever evolving. He and Hodges were the best alto players

GG I agree. Certainly in the pre-Parker period, they were the guys on the alto sax, and Benny’s style never dated. I don’t think Hodges did either, but Benny stays modern in a peculiar way. His melodies are so indigenous to him, his approach to harmony so original, and he doesn’t swing in a conventional way. When I was a fellow at the Smithsonian Critics Colloquium in D.C. thirty-some years ago, I had a polite argument with Martin Williams about who swings and who doesn’t swing. We were trying to work up a definition of it, and he said that Benny Carter was a puzzle to him because he didn’t think he swung as a saxophonist, but that he did as an arranger and as a trumpet player. I don’t agree but I know what he meant. His rhythmic approach is different. I think he swings brilliantly, but it is an intellectual kind of pacing that makes you pay attention to what he is playing. He phrases in ways that don’t fall into obvious rhythmic patterns. You are more likely to get lost in parabolas of melody than mindlessly tap your foot.

JJM Does a particular big band performance you witnessed stand out for you?

GG One of the great experiences of my music-going life is the first time I saw the Ellington band live, in Central Park in the mid-sixties. They had a series of free concerts in a beautiful setting — the skating rink, I think. The band was unbelievable. When you went to see Ellington, it wasn’t just him you were going to see; there were a dozen legendary figures in it, among the greatest musicians in the world. By the second or third number of the concert, I was so mesmerized by the band that I started walking toward the bandstand. When I got to the lip of the stage, there were a half dozen other people beside me, all of us with our jaws hanging right in front of the reed section. When those five musicians played together in unison, you could hear the cumulative sounds of the five saxophonists and clarinetists blending perfectly, almost like an organ chord. But at the same time you could also hear each individual voice in the blend. You could always hear Hodges, you could always hear Gonsalves, you could always hear Carney. That just blew my mind, to hear five completely unique and distinct individuals who could blend and be distinct at the same time. That was part of the excitement. Then there was the whole way he manipulated the band. On some pieces he would start out with long piano vamps, and you didn’t know where it was going. Each solo was set up like a beautiful little portrait in the middle of something, and then he would have background riffs for the soloists that were so lively and would seem so spontaneous — it was as though the band were improvising a duet with the soloists.

JJM Big band musicians must have faced so many challenges, one of which was how to make themselves instantly recognizable to listeners within eight measures. Who were some of the best at this?

GG Roy Eldridge is someone who comes to mind immediately. He grew up listening to people like Red Nichols first, and then discovered Louis Armstrong, which was really a transformative thing. He was very competitive with other trumpet players, but he loved the saxophone players. His brother Joe was a very good saxophonist, and he loved Coleman Hawkins and Chu Berry. Eldridge imitated their stuff on trumpet, which he thought made him seem so original, since most trumpet players take from each other. He had the facility and the harmonic savvy to play saxophone lines on the trumpet, requiring more notes and more range. His playing generated tremendous excitement because he combined that kind of fluency with rigorous, roaring high notes you can only play on trumpet. He had a “guttural” kind of sound, sometimes, where the trumpet seemed to be coming from his viscera, displaying so much feeling and emotion. All of this made his sound very distinctive, and if you were a jazz fan, you’d recognize him right off.

There were several musicians in Ellington’s orchestra — all of whom were stars — that people knew instantly from their playing. The sweet ballad statement was Artie Whetsol, and the plunger trumpet was Cootie Williams, and a similar disparity existed in the trombones, between Joe Nanton and Lawrence Brown and Juan Tizol. Who could fail to recognize Hodges or Webster or Bigard or Carney?

When people heard the Benny Goodman broadcasts, they very quickly got to know that the virtuoso trumpet player was Harry James. As a consequence of that, it was inevitable that some booking agent would come along and encourage him to leave Benny’s band to become the leader of his own. The same thing happened with Gene Krupa, who became famous for the way he looked and played — the drummer as matinee idol — that it was inevitable he would have his own band.

It was only natural for a good musician to look for his own sound. When Buddy Tate played in Basie’s band, the star tenor player was Lester Young, and most of the solos went to Lester. Buddy originally started out sounding much like Herschel Evans, who he replaced when Herschel died, but then he started to develop his own style, until he finally got his own feature on “Rock-A-Bye Basie,” which Buddy became well known for. When the band went back to Kansas City for the first time in years, it was like a homecoming. Basie knew that Buddy had a lot of friends there, so he called for “Rock-A-Bye Basie,” and Buddy told me that he stood up and played the best solo he ever played in his life. It was his way of communicating and saying hello to everybody he hadn’t seen in a long time. Yet when he finished the solo, he got a muted response, and when they walked off the stand for their break, people in the audience complained to him that he didn’t play the solo like he did on the record. He tried to explain to them that that is jazz, but even in a community like that, they wanted to hear the solo as it was on the recording, which they played to death and knew by heart.

In some cases, even the leaders wanted them to play the solo as it is on the record. The most famous example of that is probably Ray Nance’s solo on “Take the A Train.” When you listen to the three versions Ellington recorded before the one that was released, you will hear Nance play a totally different solo each time. The one on the RCA record is the perfect solo, and it is the one that became famous — somebody even put lyrics to it. The solo became so much a part of the tune that when Nance left the band, Cootie Williams became the soloist on that number, and he had to play Ray’s solo — it wasn’t about Nance anymore; his solo had become part of the tune. Ben Webster’s solo on ” Cotton Tail” is another example of that. You cannot play “Cotton Tail” without playing Ben Webster’s solo.

JJM Someone you could perhaps enlighten me on as a big band leader is Stan Kenton. He must have ten thousand records out, but I haven’t been able to get myself to listen to more than about six pieces

GG I have an essay on Kenton in Visions of Jazz, which some of my friends have referred to as “The Comic Relief” chapter. I had fun writing about Kenton because he was so pretentious and, like you, I glaze over at a lot of his records, especially from the later years. When he first started, he was sort of a Lunceford imitator, and he made some good records in that style. But he developed something of his own very quickly and had top soloists and arrangers to put it over.

The thing about Kenton is that he was very generous to guys with ideas, so he made some great records, but you have to hunt them down. He hired Gerry Mulligan as an arranger — not as an instrumentalist — who wrote some of the most influential pieces in that post-swing period. Bill Holman has said that a lot of writers changed their style after hearing his “Young Blood,” for example, and Kenton made a magnificent recording of “Young Blood.” He had great players in those days — Lee Konitz, Art Pepper, Bob Cooper, Bill Perkins, Anita O’Day, June Christy, Carl Fontana, the Candolis, Frank Rosolino — but his style was a bit pompous, and he liked pompous arrangers. The Kenton record that influenced a lot of musicians in the fifties was the one Bill Holman wrote, Contemporary Concepts, completely reinventing old standbys like “Stompin” at the Savoy” and “What’s New.” Kenton apparently wasn’t even in the studio when they recorded it and I’ve been told didn’t think it was such a great record. But Holman was a major figure in taking the dance band instrumentation and reconceiving it as a concert orchestra.

Another of his arrangers I liked a lot was Johnny Richards, who made a couple of albums under his own name in the sixties — Aqui se habla Espanol is excellent and ought to be reissued by Blue Note, which I think owns it now. It uses a lot of Latin rhythms but in a brash, dissonant, and original way, and has some dynamite solos by a young Arnie Lawrence, who passed away the other day. So, there is some stuff in the Kenton discography worth pursuing. You could put together a terrific CD or double CD of Kenton’s finest work. I love the Bob Graettinger suite, “City of Glass,” one of the most shattering avant-garde works to emerge from the forties, and I love the fact that Kenton, a commercial bandleader, recorded it in 1951 —I mean it has got to be the least commercial record ever made by a popular big band. Totally twentieth century, far-out music, and no one but Kenton would take a guy like Graettinger under his wing and say, “Do what you want to do.” On the other hand, he made self-styled progressive adaptations of West Side Story and Wagner that are as dated as most other lounge music.

JJM About six or seven years ago I saw Pete Rugolo, one of Kenton’s arrangers, lead a local orchestra, and it was really hard to sit through. At times it was engaging and I really wanted to like it, but I couldn’t get myself past the feeling that I wished I were someplace else — anyplace else — at that moment

GG I know. In the seventies, Kenton had his own record label, Creative World, which was one of the most successful independents of that period. He must have owned some of his Capitol masters, because Creative World reissued a lot of the old records. He was also recording prolifically, putting out a new record every six months or so. I played each of them dutifully, but I never got through many of them. After a while, they sounded alike, all the soloists were cookie-cutter virtuosos playing every note they could play without really saying anything. Listening to them became a very antiseptic exercise.

JJM Something tells me that very little of the remaining time I have on the planet will be spent listening to Stan Kenton records.

GG When John Lewis and I were programming the American Jazz Orchestra, he said that at some point, we would have to do Kenton. I said, “Oh, really?” He thought about it and said, “Well, maybe just one set.”

JJM There are a few bandleaders I am interested in hearing your comments on, the first being Paul Whiteman …

GG Whiteman is a much more interesting figure than a lot of us made him out to be; during a brief attempt at a Whiteman revival in the seventies or early eighties, I wrote that the revivalists were attempting to make a lady of Whiteman — Whiteman had once been lauded for making a lady out of jazz. Anyway, they knew what they were doing, and it took me a long time to catch up. There was much resentment toward him because he was a big, fat, white guy known as the “King of Jazz.” It is important to remember that he got the nickname after the Aeolian Hall Concert in 1924, where he debuted Rhapsody in Blue, and in those days, many people thought Rhapsody in Blue was the ultimate jazz work. What I find scary is that there are still people who believe that. A Gershwin piece in the New Yorker recently got Jerry Wexler so mad he called me to commiserate about a canard we thought was put out of its misery fifty years ago.

Whiteman’s big idea was that native elements in American music — swinging rhythms, diverse instrumentation, peppy tunes, blues scales — could be the basis of some sort of popular classical music. But by 1926 and 1927, when Fletcher Henderson’s band was established, and Ellington had come to town, and Chick Webb was doing well, he realized he was on the wrong train. Jazz wasn’t a native resource; it was the art itself. He grew to like jazz and wanted to hire black players, including Eubie Blake, who was a good friend of his, but his management told him he couldn’t do it. They told him that if he hired black musicians, not only would they lose the South and much of the North, but that the players would be humiliated — they would have to use separate entrances, wouldn’t be able to eat with the band, etc. So Whiteman said that if he couldn’t hire black musicians on stage, he would hire them off stage, and he ended up hiring black arrangers, as Vincent Lopez also did. He bought arrangements from Fletcher Henderson, Fats Waller, and hired William Grant Still, who wound up writing more arrangements for him than just about any one. So now he wanted to have a more authentic jazz sound.

The first guy he hired who he thought could appeal to a jazz audience, oddly enough, was Bing Crosby. Up until that time, Crosby was a vaudevillian who hadn’t been heard outside of California and the Northwest. Whiteman hired Crosby based on the recommendation of two musicians in the band who had seen Crosby in a vaudeville show. Without ever hearing him, he called Crosby and his partner Al Rinker to his office, offered them a job, and arranged for them to join up with the band in Chicago. Soon after that the Goldkette band fell apart, and Whiteman hired the best guys — Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer, Eddie Lang, Joe Venuti, and others, not least arranger Bill Challis, an original who wrote many of Whiteman’s best numbers. A war broke out between the old guard in the band, which had made the band popular, and the new, which Paul seemed to favor. Henry Busse was the best-known trumpet player in the world at one point because of his work with Whiteman, but couldn’t play a lick of jazz. His idea of jazz was to put a mute on the horn and play a coy “wah-wah.” He disdained Beiderbecke and so, along with a couple of other guys in the band, quit in the middle of a record session. Whiteman went along with the jazz guys.

During the years, 1927, 1928, and right through 1930, Whiteman had a pretty great band that made a lot of wonderful jazz recordings. Challis was the hippest white arranger up to that point — even Duke Ellington was a Challis fan and later commissioned him to write a couple of pieces, and Benny Carter mentions Challis as an early influence on him. Challis was a resourceful, stubborn man, and Whiteman gave him total freedom to write what he wanted to write. But when the depression hit, the jazz audience started to fall apart, and Whiteman fired most of the jazz guys except Jack Teagarden and Mildred Bailey, and basically returned to the concert hall, pseudo-jazz that had made him famous in the first place. He managed to do okay with that through the thirties and forties, but in the fifties he began to fade, and was little remembered when he died, in 1967, I think.

Yet he was the first bona fide American twentieth century musical superstar. In the twenties, he was as famous as Charles Lindbergh. Every time he pulled into a city there were fans greeting him at the train station. When he came back from Europe, the mayor greeted him at the dock, and a skywriting plane wrote, “Welcome home Paul.” It was practically a holiday every time he returned to Grand Central Station, with hundreds of people and press in attendance, and a police escort to take him to City Hall. He was a huge star. And you have to give him credit, because he was ahead of his time. He didn’t initially understand where jazz was going, but once he did, he was a generous man and an articulate spokesman for American music. He gave an important commission to Ellington, and he gave Billie Holiday her one hit record in the middle part of her career, “Trav’lin’ Light.”

JJM It sounds as if he was a decent man then, because if you read Ralph Berton’s Bix, you may be left with a different impression of him

GG That is a vicious book, and no one takes it too seriously as a work of history. I did a lot of research on Whiteman, and wrote at length about him in my Crosby book. Berton goes along with the standard caricature, blaming him for Bix’s tragedy, when in fact he did everything he could for Bix, putting up with more than a lot of bandleaders would have taken.

Whiteman was an interesting guy. His favorite movie was Sunrise by F. W. Murnau, which is one of the great films of all time. He had managed to acquire his own 35 milli-meter print, which he watched all the time, and he totally fell in love with the actress who plays the femme fatale in the bullrushes who seduces the hero and almost ruins his life. When he went to California to make King of Jazz, he met her on the Universal lot. They married, and stayed married until his death. So he was a romantic, and by all accounts a decent man. Crosby argued with him when he left the band, and stayed mad for a long time, but in later years, he admitted he should have been on his knees thanking Whiteman for his big chance. Whiteman was a disciplinarian, but a witty guy. There’s a great story about Whiteman and Crosby. Crosby was a terrible drinker in the twenties, occasionally blacking out or not showing up, playing golf all day. Many years later, when Bing was the biggest thing in show business, someone asked Whiteman if Bing had been hard to work with. Whiteman said, “Bing wasn’t hard to work with, but sometimes he was hard to find.”

JJM How about Earl Hines as a big band leader?

GG I love Hines. That’s another band due for rediscovery. It is really amazing how critics historically have been at the mercy of what the labels put out. For example, Columbia released a Lunceford collection when I was in high school. It got a lot of attention, and I bought it and became an instant Lunceford fan. But if they don’t put out a new CD, an entire generation or two of jazz fans — some of whom will become critics — will not have Lunceford’s music in their background. Hines was still very big when I was growing up. He lived a long life — until 1983 — wearing that huge toupee, playing a lot of piano, and probably staying on the road a little longer than he should have.

Hines had a major band in the thirties. He was in residence at the Grand Terrace Ballroom in Chicago, playing under a pretty strong contract that didn’t give him a lot of discretionary time to tour the country, and I think that is one of the reasons his band never quite got the national attention others did. He had a pretty star-studded group, but it was a Chicago phenomenon, even as it became a kind of incubator for the bebop movement. So many great musicians were in his bands; Billy Eckstine was his vocalist, Sarah Vaughan was vocalist and second pianist, Budd Johnson was his main soloist and an arranger, and Alvin Burroughs was his very distinctive drummer. The band swung like crazy. A lot of pieces were three-minute concertos featuring Hines, but he had a lot of diversity, ranging from blues to modern pieces, including some splendid ballads that he wrote. Again, an anthology of his best pieces would provide a handle on what that band was about.

JJM Did he reluctantly join Armstrong’s All-Stars?

GG I don’t know. At first, he probably wasn’t so reluctant because it really was comprised of all-stars. At the time, Armstrong was the most famous figure in jazz. His band had finally folded, the war was over, and it was a big deal to have him return to a small-group format with some of the most celebrated jazz figures in the world: Jack Teagarden on trombone, Barney Bigard on clarinet, Earl Hines on piano, Sidney Catlett on drums. Nobody could be reluctant about being in that band. But it turned out to be a phenomenal success and I imagine it became increasingly galling for a man who had been a leader all his life to now be a featured sideman, even with Pops.

Things weren’t great in the jazz world for a lot of musicians then. Teagarden loved the security, and Hines probably needed the security and liked it, but I think he resented being second banana. He had been second banana to him at the beginning of his career, in 1928, when he made those Hot Five recordings, and here he was, after twenty years at the helm of a great orchestra, being second banana again. People were not coming to hear him. As guys left the band, they were replaced by very good musicians, but not stars of the original group’s caliber. As great as trombonist Trummy Young was with the Lunceford band, he was not a celebrity the way Teagarden was, and Billy Kyle was not a celebrity the way Hines was. The band was always called Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars, but it became less and less an All-Star group until, by the end, most people had never heard of most of the players in the group.

Hines had a bad spell in the fifties, when he was playing Dixieland joints in San Francisco, but then a magical thing happened for him. He was rediscovered in the early sixties after doing a couple of concerts in New York that Dan Morgenstern helped organize. The concerts received tremendous attention, great reviews and international press, and suddenly everybody was saying that this guy from the twenties was the hottest piano player around, a premature avant-gardist. He recorded prolifically, and made albums with titles like Spontaneous Explorations. When I was studying in the south of France in 1967, I picked up an album he did for Fontana called Blues in Thirds, which is still one of my favorite Hines albums. He was turning records out, one after the other, many of which were solo piano albums that had ten or twelve minute tracks on them. A particularly great album was his reinterpretation of the 1928 sides he recorded for QRS. Hank O’Neal produced that one for Chiaroscuro and called it Quintessential Recording Session; he also recorded Hines in duets with Joe Venuti, Hot Sonatas.

JJM The music of Lionel Hampton still holds up well

GG He was a unique figure because he had a jazz band that doubled as an r&b band; he had two audiences simultaneously. The jazz world frequently hated the r&b stuff, which I often found tremendously tedious. There are dozens of film clips produced for television shows in the fifties of him playing that stuff, all quite repetitious. But at the same time, he would come up with something like “Flying Home,” which has an r&b feeling to it, but it is a great jazz record, featuring a classic tenor solo by Illinois Jacquet.

Hampton started off many singers like Dinah Washington and Betty Carter, and he always had great players in the band. After Illinois Jacquet came Arnett Cobb, a fascinating musician who eschewed licks. Except for Teddy Wilson, Hampton probably fronted the greatest series of small band recordings of the Swing Era. His series was made for Victor and Teddy’s were for Brunswick, but they were similar in that they used the best musicians from the big bands. Not surprisingly, the Wilson sides are more genteel than Hampton’s, or at least they don’t have any of Lionel’s showboating. But you could also argue that Hamp was a bit more cutting edge, using guys that hadn’t quite made it yet like Nat King Cole and Charlie Christian, and he had all the great saxophone players, except Lester, and had them work in tandem. RCA put out the complete small group Hampton series on LP — not on CD. The best of them stand up as among the most exciting records in jazz history. Hampton was indefatigable, and of course a great vibes player, at his best absolutely timeless — he could be himself with Dizzy, Tatum, Chick Corea, anyone, and never sound as if he represented another era. He had a brilliant sense of harmony, and the kind of rhythmic power that could rock anyone. But I also felt he stayed out on the road a little too long. He was out there playing after a stroke, when he had only one functioning arm, yet people came to see him. He lived for the audience but they weren’t seeing the real Lionel; they were seeing a memory — maybe that was enough.

JJM One of the great composers and arrangers of the bop era was Tadd Dameron.

GG Tadd Dameron was terrific. He was one of the great arrangers to come out of Kansas City, but another tragic figure who got caught up in drugs. He wrote for Harlan Leonard’s band, then came to New York and was given a chance to put together a group in a chicken restaurant, and was so successful that the gig lasted for something like seven or eight months. Fats Navarro played with him, and he had two great tenor players, Allen Eager and Wardell Gray. He wrote many wonderful tunes, some of which became jazz standards. He wasn’t a great pianist — he played what they called “arranger’s piano” — but he conducted ably from the keyboard and invariably got the best from his sidemen. A lot of his tunes are sort of at the nexus of swing and bop, modern in terms of the harmonies, but animated by powerful rhythms and lovely melodies. I hear Tadd’s influence in a lot of the pop/jazz writing used in the TV shows and film scores of the late fifties. I think some of the compositional ideas reflect Tadd’s work; you had to know a little about music to get a grip on them. He used fewer notes than the bop virtuosos, yet packed every measure with ideas and feeling. He could really set a late-night mood.d challenging music came from the avant-garde orchestras.

GG There were a lot of wonderful avant-garde orchestras, and certainly the longest lasting one — which lasted almost as long as Basie or Ellington — was Sun Ra’s. He started out in the late forties, and by the mid-fifties its nucleus of musicians and singers was a world until itself. He manufactured his own records and kept at it for decades, until he finally achieved international renown in the last twenty years of his life. He started out as a pianist with Fletcher Henderson, so he had the whole big band history in his bones, but he took tremendous chances and moved way beyond the norm, combining far out jazz with r&b, doo-wop, aleatory music, you name it.

In a different way, Gerry Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band was one of the great orchestras. We don’t think of it as avant-garde because its music is so melodic, but Mulligan’s band announced in its very name that dancers were not welcome, and he hired many of the most adventurous writers of the day: Bob Brookemeyer, who was by far the most prolific contributor, Al Cohn, George Russell, John Mandell, Gary McFarland. Each of these guys made his mark on the music. Russell is one of the most formidable figures in jazz orchestration, going back to his Cubana Be and Bop charts for Dizzy in the forties, and his various bands and extended works from the fifties on, which helped to establish Bill Evans, Eric Dolphy, and Sheila Jordan, among others. Anyway, Mulligan encouraged writers to go the distance, and provided a crack orchestra to make the most of what ever they came up with.

There have been a lot of fine avant-garde bands during the last twenty years. I really miss David Murray’s Big Band, who had phenomenal consistency in his weekly performances at the Knitting Factory. The Ellington concerts he did, but has yet to release on records, were some of the highlights of my music-listening life. He was kind enough to give me tapes of them, but he never managed to get them out. James Newton wrote the arrangements, which were wholly original yet empathic interpretations of Ellington. He wrote some wonderful music, and also transcribed the Paul Gonsalves solo from “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” that Ellington performed at the 1956 Newport Festival. David has the whole orchestra play it. Unreal!

JJM I used to love Carla Bley …

GG Oh, yes. She was around for a long time, then went off to Europe. I never really got into the early recordings, though I loved the things she wrote for Charlie Haden and Gary Burton. I don’t know why I missed out on her own band recordings — I guess I just slept on them. When she came to New York a couple of years ago, I went to see her at the Iridium and it knocked my socks off. An absolutely phenomenal band, so fresh, so witty, so original, and every soloist in the band killing, powered by a great rhythm section with Steve Swallow on electric bass. She gets the best out of her players — Lew Soloff, Andy Shepherd. Do you know Gary Valenti? My God, one of the best trombonists around, plays with the thrust of small hurricane. Tina Pellikan at ECM was kind enough to fill me in with a bunch of Carla’s CDs, so I’ve been making up for lost time. Wonderful orchestra, and Bley is a wonderful musician.

JJM She did an album called Musique Mechaniqe in the late seventies that I played the hell out of.

GG Yes, somebody should do a retrospective of her music. The people whose work I would most like to see retrospectives of while they are alive to take bows are George Russell and Bill Holman, who is unknown in New York, Carla, and Gerald Wilson, who has also been ignored in New York. We did a concert with him and the American Jazz Orchestra. You know the line about being able to shoot deer in a theater? We didn’t care — it was intoxicating to watch him work and listen to his music. He came to Birdland last summer and played two magnificent evenings, and thank goodness the place was packed. But for some reason, even though he has been a dynamo of West Coast big band music for well over half a century — going all the way back to Lunceford in 1939 — he is practically unknown on the East Coast. When I told the publicist who worked with the American Jazz Orchestra concerts that I wanted to do Gerald Wilson, he pleaded with me not to because he didn’t know how to sell him to the press.

JJM I picked up a recently released CD of his about four or five months ago, and I thought it was pretty cool.

GG Yes, a terrific record. Basically what he did is rework some of his classic arrangements on that, played by a mixture of established and unknown musicians. His band has always had great spirit, and his writing is filled with surprises. His son Anthony is one helluva guitarist.

JJM During this ongoing process of writing Crosby’s biography, you must have had to do a ton of research around the swing era. In my own time spent on that era while preparing for this conversation, I ran across names I hadn’t heard in years, like Gus Arnheim, for example What did you learn about the big band era that perhaps you didn’t know before going into the work on Crosby?

GG Arnheim had a smooth dance band. In a way, he was a West Coast Whiteman, like Leo Reisman, except that Reisman hired Bubber Miley for a few wonderfully evocative jazz recordings. “What Is This Thing Called Love” is a must-hear. Arnheim wasn’t a jazz musician, but as I said earlier, the definitions of jazz were not yet set in stone in the twenties and early thirties. People were still fighting over it. The best example I can give you is the 1956 edition of World Book Encyclopedia my parents bought for me when I was a kid. I can recite from memory the entire entry for jazz: “Jazz: see Gershwin, George.” That’s it. So to many people who came up during that period, anything that was sort of swinging and that you could dance to was considered jazz. Today we have a higher plateau in the sense that jazz has become an aesthetic word, and we use it to describe musicians who improvise, swing, and use blues and other scales. But jazz is also a music that remains modern and timeless, which most pop music posing as jazz — from Arnheim to Kenny G — isn’t.

If it wasn’t for Bing Crosby I don’t think anybody would have listen to Gus Arnheim records. Crosby gives those records their rhythmic interest, because he had a jazz feeling and background. Listen to “One More Time,” for example, or any number of Whiteman things, like the way he phrases “Mary” or “You Took Advantage of Me,” or the totally forgotten song, “Lovable,” which has a great line –” Others just imitate / kisses that you create.” There were millions of jazz bands in those days, many are not remembered anymore, and some were damn good. One of the big surprises for me in researching Crosby’s early years was when he talked about dance bands that would come through Spokane. I would call up some specialist and ask if he had tapes on those bands, because I had never even heard of some of these people. The tapes I got sounded pretty dated, especially during the vocals, but the amazing thing is how many hundreds if not thousands of talented young musicians were trying to imitate what they heard on records, inserting whatever jazz licks they could into what were basically very staid dance band arrangements. In the Northwest, the bands were mostly white, but at the same time there were just as many black bands working the Midwest and Southwest. They weren’t concerned with what the new music was called, only with grabbing a piece of it.

JJM Big band music, to my ears, still sounds exciting after all these years.

GG One of the reasons jazz from that period is so infinitely exciting is because you can hear them inventing the art. Musicians were growing up, getting the music in an aural tradition — partly from radio and partly from records — but mostly on the road, apprenticing in big bands, getting jobs with local groups, going to the big cities, building a reputation, and, in relatively few instances, going from sideman status to leader. Today, the majority of musicians go from the university to a profession, which is quite different. During the big band and swing era, there were guys growing up in California listening to bands on the air or in local ballrooms, or growing up in Kansas City, Chicago or St. Louis, listening to the bands out there. Today, everyone goes to the university, getting similar instruction, memorizing the same solos, worshipping the same legendary figures. Individuality is harder to come by; the good news is that when we hear it, we are more inclined to appreciate it. Musicians and critics once criticized Lester Young because he didn’t sound like Coleman Hawkins. Today, when someone comes along with his or her own sound, we light incense, fall to our knees, and shout hallelujah. Well, at least we should.

____________________

This conversation took place on May 10, 2005

Giddins is so knowlegeable and also accessible. I’m an older listener and grew up on the 30s bands, including Lunceford. The Benny Carter/Savannah Churchill side is “Hurry Hurry.” But don’t forget “Poinciana” and “Malibu” from that same period. Mosaic has them on its Capitol Classic Sessions set. And don’t forget his trumpet playing during this 40s period either. Thank you, Gary Giddins.

I’ve read two of Gary’s books and enjoyed them immensely.

With respect to Kenton — he hired great arrangers, most notably Mulligan, Shorty Rogers, Paich, Rugulo, Holman, Bill Matheiu, Richards, Dee Barton, Gene Roland — let them do their thing, and did his best to record them well. If you don’t dig Rugulo writing for Kenton, check out his glorious writing for June Christy. Thad was also a wonderful writer for singers — check out his charts for Joe Williams, Ruth Brown, and Bill Henderson (“My How The Time Goes By” is exhibit A).

I view the Mulligan Big Band of the 60s and the Thad/Mel band as the culmination of the Big Band continuum, and worthy of consideration with Duke and Basie. Holman and Johnny Mandel are still at it, turning out great work, and Brookmeyer, certainly in the league of the greatest writers (and a very interesting player), left us a few years ago with a masterpiece called “Standards.”

Also in the under-appreciated category I’d include Maynard’s band of the 50s and 60s, with great writers and great players.