.

.

.

“Nat King Cole: The Shadow of the Word” is one of several photo-narratives in Charles Ingham’s new series devoted to his love of jazz music, “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives”

These photo-narratives are provocative and meaningful– connecting time, place, and subject in a way that ultimately allows the viewer a unique way of experiencing jazz history.

To enhance the opportunity for appreciation of this artistic series, in the coming weeks “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives” will be featured on Jerry Jazz Musician three-at-a-time, and will include the artist’s description of each piece.

.

.

This edition’s narratives, found below the artist’s introduction, are:

.

“Nat King Cole: The Shadow of the Word”

“Slain in Cold Blood”

“Local 767: The Black Musicians’ Union”

.

.

_____

.

.

Charles Ingham introduces his “Jazz Narratives” series

.

…..Jazz has always been there for me. Music is an essential part of my life, and I have eclectic tastes, but there has always been jazz music. At seventeen, I’m at a Rahsaan Roland Kirk concert in my hometown of Manchester, England, stunned by the transgressive beauty of this man’s performance. At fifty-seven, my wife has died, and I can’t bear to hear lyrics, so it’s Kind of Blue and Trane ballads. And today I’m listening to ‘Round Midnight, Monk alone at the piano, stunningly honest and almost unbearably intimate.

…..So as an artist I need to give something back, but make it my own, and make it new.

…..As a conceptual artist, my photo-narratives are hybrid forms, transgressing distinctions between the verbal and the visual: the image as text. My art represents a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis: the words, the images (abstract and referential), the space between images, the subjects, the reference to specific individuals, places, or times. As the artist Alexis Smith says of her collages and assemblages: “It’s fused into a whole where they seem like they’ve always been together, or were meant to be together. The people that look at them put them together in their heads.” Some visual references are obvious; some of the bones, sinews, and other connective tissue that hold a particular narrative together work within the piece’s own logic, a logic that viewers find for themselves. Here, the artist makes the work, and that work has an agenda, but a significant part of that agenda is for the viewer to find something of (or for) themselves within these images and words.

…..Each work in this series of “Jazz Narratives” is anchored by a person (a musician) and a related place. I am especially interested in the “aura” of these places. Sometimes, the place remains relatively unchanged seventy years after the musical fact; sometimes, only a physical street number remains, if that. What matters is that, for the artist and the viewer, this aura remains. This, say, is 151 Avenue B, on the Lower East Side; the brownstone is easy to miss if you are walking along the east side of Tomkins Square Park, but if you know that Charlie Parker lived there, it has become something more than the stone and glass of the place. 4201 S. Central Avenue, Los Angeles, is an anonymous mixed-use building, but there’s the number above the glass doors; 4201 S. Central is the Downbeat Club. Here, in 1945, Clora Bryant first heard bebop: here, on this corner, and that corner is still here, as is that night and all those other nights.

…..Some years ago in Brooklyn, I went looking for 99 Ryerson Street, where the poet Walt Whitman had lived when Leaves of Grass was first published. The fact that Whitman had lived here had only recently been discovered, and the 1850s wood-frame house was unmarked and unchanged except for aluminum siding and the addition of an extra floor. It is the only surviving Whitman residence in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Standing on the original bluestone sidewalk slabs, I was looking at Whitman, whose vision of America was a primary reason for my decision to emigrate to the United States. In my excitement, I crossed the street and spoke to an elderly man sitting on the stoop opposite. “Do you know that Walt Whitman lived in that house?” I asked, clearly appearing to be a madman. The neighbor looked up at the crazy person: “Is that the guy who is renting a room?” For him, the aura was not visible.

…..These pieces are works of homage; I am making some kind of unsentimental pilgrimage to each of these apparently anonymous street addresses. And I am conjuring ghosts; they are still alive in these places as they are in their recordings. The music may have been recorded in 1947, but they are playing it now. You can hear that. And, if I am successful, you can see the musicians in my art.

.

_____

.

.

.

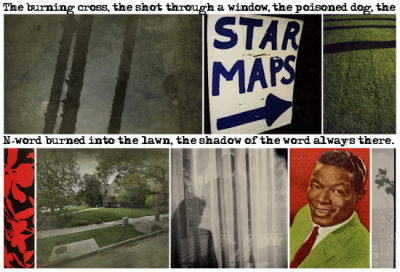

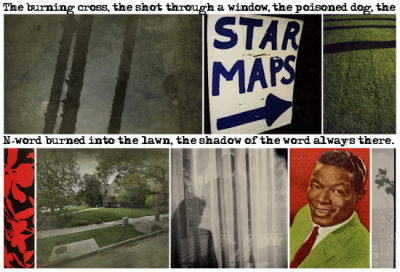

Nat King Cole: The Shadow of the Word

(401 South Muirfield Road, Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..

…..Arriving on Central Avenue from Harlem, the pianist Gerald Wiggins said of Nat Cole, “[Y]ou ain’t never heard such piano. Oh, man. He was a good player. I was sorry he started singing.”

…..Of course, Wig is not the only one to express such regret, a regret that for some would become outright condemnation at Cole’s “selling out” to popular music and abandoning the intense, improvisational freedom at the keyboard that seemed to be leading the pianist toward bebop.

…..However, Cole’s transition from hip to square (if that is what it was) did not necessarily make life easy for Nat King Cole (even if there is an ethnic subtext in “hip to square”). The Coles moved into 401 South Muirfield Road in August 1948, and, as is well known, their Hancock Park neighbors’ racist attacks became well-organized and vicious. A sign with the words “N-word Heaven” was posted on the front lawn of the Coles’ Tudor mansion; their dog was poisoned; a shot was fired through a window in November. For Nat Cole, born in Montgomery, Alabama, such tactics were not unfamiliar, but on one occasion his Chicagoan wife Maria chased off cross burners while dressed in a nightgown and wielding a rolled-up newspaper.

…..When Hancock Park was established in the 1920s, it was put under a 50-year restrictive covenant, which stated that non-whites could not live in the neighborhood, unless they were servants; however, in May 1948, the Supreme Court decision in Shelly v. Kramer rendered segregated housing illegal. Nat and Maria knew this.

…..The attacks on the Coles’ house diminished, but Cole’s oldest child, Carole, remembered the N-word being burned into the front lawn: “The shadow of that word was just always there.” Will Friedwald, in his 2020 biography of Nat King Cole, notes that Carole “meant that literally, not symbolically.”

…..The Coles’ neighbors in this “last WASP enclave” of LA could go back to listening to the Nat King Cole records that had been in their dens all this time.

.

.

___

.

.

.

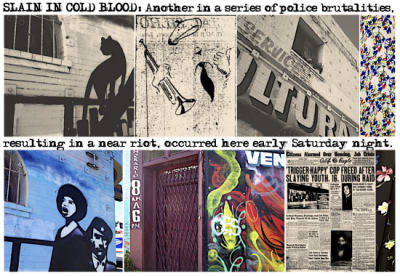

Slain in Cold Blood

(4071-4075 S. Central Ave., Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..Founded by John J. Neimore in 1879 as The Owl, the newspaper was intended to serve the burgeoning black population of Los Angeles during the Great Migration. Purchased by Charlotta Bass upon Neimore’s death in 1912, the paper was renamed the California Eagle, and owned and operated by Bass until 1951. Having once boasted a circulation of 60,000, the West’s oldest African-American newspaper, the Eagle ceased publication in 1964.

…..As the viewer will see from the headlines on the front page of the November 1943 issue of the Eagle, the newspaper was a pioneering force in the multi-ethnic civil rights movement. The all-too familiar story about the “Trigger Happy’ Cop” attests to the paper’s position, as does the story “Critical Housing Crisis and Job Bias Viewed With Alarm.” The article “Thousands March Against Smith; 49 Pickets Nabbed” covers protesters surrounding Polytechnic High School, where Gerald L. K. Smith was due to speak. Smith, an extreme-right clergyman, racist, and anti-Semite, formed the America First Party and joined the pro-Nazi Silver Shirts organization, patterned after Hitler’s brown shirts. At the time of the article, Poly was located downtown, on the corner of Washington Boulevard and Flower, two miles northwest of the Eagle’s office on Central Avenue. Graduating six years before this article, Tom Bradley, LA’s only African-American mayor, Tom Bradley, had been a student at Polytechnic High School.

…..In 1942, Bass would be interrogated by the Department of Justice, following entirely logical claims that the paper was funded by Japan and Germany. The FBI, perceiving Bass to be a Communist, monitored her activities into her nineties.

…..Although Bass is often regarded as the first African-American to own and operate a newspaper in the United States, the anti-lynching campaigner Ida B. Wells became editor and co-owner of the Memphis newspaper The Free Speech and Headlight in 1889. This fact should in no way detract from the achievements or substance of Charlotta Bass, and, indeed, the two women have much in common. In 1952 Bass ran for Vice President of the United States, representing the Progressive Party, her slogan, “Win or lose, we win by raising the issues.”

…..In addition to calls to unionize aircraft-manufacturing workers and other activist issues, the pages of the Eagle covered crime, sports, retail advertising, church services, entertainment news and events, and a column entitled “What’s Doing in the Younger Set.” The Dizzy Gillespie image in the top row of images in my piece comes from a later issue of the paper, appearing above a caption that reads: “WELL, WELL, WELL! Dizzy Gillespie, the young man with the horn, who came up with a new idea in music is now out with a brand new idea in photographs. The above picture is the release ‘photograph’ of the great Diz and, according to his managers, this will be the only picture to be released on Dizzy in the future. The goatee, beret and horn are so exclusively identified with Mr. Be-Bop that a picture with the complete visage is not deemed necessary.”

…..The building once occupied by the offices of the California Eagle still stands, on the corner of Central Avenue and East 41st Street. Now occupied by an appliance store, it is an elegant two-story building that curves around the street corner. Appropriately, the southern wall boasts a mural entitled La Cultura Cura (“Culture Cures”), #PAINTLA. The mural celebrates the alliance between the Black Panther Party and Los Boinas Cafés (“The Brown Berets”), the pro-Chicano organization that at its inception was known in part for its direct action against police brutality. Charlotta Bass knew exactly what they were talking about, and what we continue to talk about.

…..The title of this work comes from the Eagle’s front-page headline story on November 29, 1945. The piece recounts the murder of a black GI by an off-duty white Long Beach police officer after a traffic stop. Mitchell H. Mason had been discharged from the army two months before his death, after serving eighteen months overseas. The officer claimed later that Mason had approached him with an open knife. “Investigators said that they were unable to find any trace of a knife.”

…..When I was working through the photographs that I had taken of the 41st Street wall, I noticed that, serendipitously, I had captured an image of the stylized eagle on the side of a USPS van stopped at the Central Avenue light.

…..The entrance to S & J Appliances is on the corner of 41st and Central, and another mural is painted on the Central Avenue wall. This gorgeous, swirling abstraction, by the Clover Signs, also carries the store’s phone number and Lavadoras y Refrigeradores, Venta y Reparación (“Washing Machines and Refrigerators, Sale and Repair”). My image of the door (with the store’s hours) appears to comprise three images; however, it is in fact a single photograph. From right to left: mural, door, and a glimpse of the rounded corner of the blue south wall.

…..The word Venta is unambiguous, although in my photograph one reads only the first three letters. Serendipity again, perhaps, or Charlotta Bass unambiguously pointing out to us that these are the first three letters of another word: Venceremos.

…..We shall overcome.

.

.

___

.

.

.

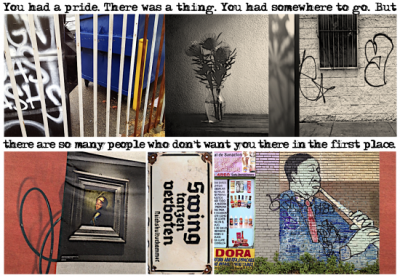

Local 767: The Black Musicians’ Union

(1710 S. Central Ave., Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..1710 South Central, the former home of the Black Musicians’ Union, was a frame house with offices on the ground floor. The kitchen hosted fish fries and the backyard held oil-can barbecue pits. Upstairs were practice and rehearsal rooms. Local 767 was a place to find work, to hang out, to make connections, and to rehearse.

…..The building is gone now, replaced by anonymous industrial bunkers. The 10, the Santa Monica Freeway, built in 1965 and one of the busiest freeways in the world, cuts through the neighborhood, running parallel to or obliterating what remains of E. 17th Street at Central Avenue.

…..In 1953, one year before Brown v. Board of Education, Local 767 merged with the white musicians’ union, Local 47. The amalgamation was not simple.

…..Speaking in 1996, Cecil “Big Jay” McNeeley remembered, “I used to go down to the black musicians’ union, Local 767. They used to have Dexter Gordon and all the guys down there rehearsing on Central Avenue. So I used to go down and listen to the guys. My brother was playing in the band. I wasn’t even playing then, but I’d go down and listen to them play.”

…..Born in Watts, and known mainly as a rhythm and blues saxophonist, McNeeley had roots in bebop and, in addition to his own bands, played with everyone from Cab Calloway and Lionel Hampton, to Little Richard, and the Modern Jazz Quartet. In Central Avenue Sounds, McNeeley talks of how white culture and its writers were baffled by the fact that he was drawing a huge white audience. “I know one guy wrote up—I played at Huntington Beach [in conservative Orange County, south of Los Angeles], and he said that it looked like a thousand Watusi dancers!”

…..McNeeley speaks of being against the merger of Locals 767 and 47, when the black musicians “gave up the property, the money, everything. . . . They hired a couple of blacks, and that’s it. And when a job would come in, you’re not going to get it, man. Let’s face facts. A job comes in, a black musician is not going to get it. They’re going to call in one of their boys. It’s all politics. It’s the same thing as the politics that we have today in the country. . . . Yeah, with 767 you had an organization that at least looked out for you. It was great. We had our own local, we had our own money, we owned the building. If I was on the road traveling and got into trouble, they sent me money. They realized the problems that we had.”

…..In contrast, pianist Gerald Wiggins felt that Local 767 often held too much sway over where and when musicians played, a union representative sometimes even pulling a musician off the stage when playing at an after-hours club. Wiggins felt that while many members of Local 767 feared the outcome of the merger, “In fact, it opened up more opportunities for them.”

…..Of the amalgamation, the trumpet player Clora Bryant recalls, “I wasn’t part of it. They weren’t looking for any females to be a part of it. It was a male thing. They didn’t have women’s lib. It was the ones who had the desire to be part of the [TV and movie] studio scene. . . . And nobody was knocking the door down to record women.”

…..Forty-three years after the amalgamation, Bryant still felt a sense of loss and discomfort in the merged union. “We lost money. There was a little prestige [at Local 767] that you could never capture over at the white local. And it’s become even less than when we first went there. Now there’s no . . . Oh, they treat you like a piece of dirt over there now. There’s no pride. You had a pride. You had somewhere to go and see your peers who were on the same level with you and could talk about the same things you talked about. . . . You’d walk in there [1710 S. Central], and there would be Basie’s band upstairs rehearsing or Duke Ellington’s band or Benny Carter or Nat King Cole, you know, or Lloyd Reese would be rehearsing those kids on Sunday, upstairs. There was a thing. But we go out here [Local 47], and the minute you walk in, you feel a coldness, because there are so many people there who don’t want you there in the first place.”

…..The fact, however, that a workers’ union should remain segregated until eight years after the end of World War II recalls the wartime “Double V” movement, calling for victory over fascism abroad, and victory over racism at home. Indeed, the writer Chester Himes would leave Southern California for Europe, “shattered” by the “mental corrosion of race prejudice in Los Angeles.” And Lawrence P. Jenkins, in his biography of Himes, suggests that “for Chester, without a home front victory, the future could hold only a major or minor version of Nazism.”

…..In the lower row of images in Local 767, the viewer will find an upended sign: Swing tanzen verboten. Reichskulturekammer (“Swing dancing is forbidden. Reich Chamber of Culture”). In the Nazi reading of culture, swing dancing was Entartete Musik (“Degenerate music”), swing being tied to that “damnable jazz,” and jazz music as being perceived as a Black-Jewish hybrid. Under the Reich, an underground swing movement developed and became a threat to fascist orthodoxy. In wartime Germany, listening to swing could get you sent to the camps; in wartime Los Angeles, listening to swing on Central Avenue could at least get you badly beaten by U.S. sailors or the LAPD.

…..(For further reading on the home-front struggle for a double victory and the relevance of the concept of Entartete Musik in Nazi Germany and at home, I recommend the article, “Should I Sacrifice My Life to Be Half American?” in the September 24, 2018, issue of Jerry Jazz Musician.)

…..The mural to the right of the anti-swing sign can be found on E. 41st Street Place, on the side wall of Perla Sobadora at 4124 S. Central. The unsigned mural, of which my photograph is merely a detail, is thirty feet long and depicts images of two other musicians.

…..To the left of the sign is a collage, drawn in part from a New York Times article, “The Dutch Golden Age Wasn’t All White,” a review of an exhibition in the Hague that considers the 17th century’s overlooked paintings of Black subjects (25 March 2020).

…..There was a thing. Not a thing to be demeaned. Not a thing to be ignored.

.

.

___

.

.

All pieces are archival inkjet prints, 4½ x 6½ inches, framed to 14 x 14 inches. For more information, visit charlesingham.com

.

.

To see Volume 1 of this series, click here

To see Volume 2 of this series, click here

To see Volume 3 of this series, click here

To see Volume 4 of this series, click here

To see Volume 5 of this series, click here

To see Volume 6 of this series, click here

To see Volume 7 of this series, click here

To see Volume 8 of this series, click here

To see Volume 9 of this series, click here

.

___

.

.

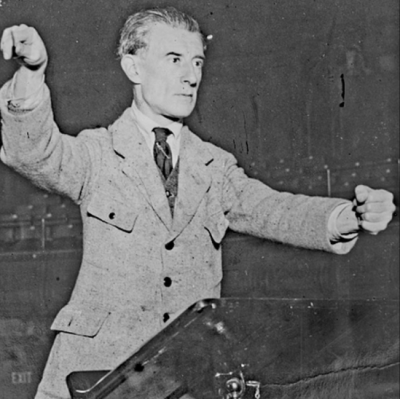

photo by Jacqueline Ramirez

.

Born and educated in England, Charles Ingham moved to California in 1982. He has always been interested in hybrid forms and the intersection of literature and the visual arts, his photography often seeking to transgress the traditional boundaries separating the verbal and the visual.

Ingham lives in San Diego and shows his work at Distinction Gallery in Escondido. He recently had three pieces accepted for the 28th Annual Juried Exhibition at the Athenaeum Music and Arts Library, La Jolla. He also had two pieces shown in the “Six-Word Story” exhibitions at Front Porch Gallery, Carlsbad, and the Oceanside Museum of Art.

His work can be found.at his website: charlesingham.com

.

.

.

.

.

.</span