.

.

.

“Lionel Hampton: Central Avenue Breakdown” is one of several photo-narratives in Charles Ingham’s new series devoted to his love of jazz music, “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives”

These photo-narratives are provocative and meaningful– connecting time, place, and subject in a way that ultimately allows the viewer a unique way of experiencing jazz history.

To enhance the opportunity for appreciation of this artistic series, in the coming weeks “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives” will be featured on Jerry Jazz Musician three-at-a-time, and will include the artist’s description of each piece.

.

.

This edition’s narratives, found below the artist’s introduction, are:

.

“The Entrance of Bessie Smith into San Diego”

“Lionel Hampton Is Coming to Dinner at Dr. Gordon’s House”

“Lionel Hampton: Central Avenue Breakdown”

.

.

_____

.

.

Charles Ingham introduces his “Jazz Narratives” series

.

…..Jazz has always been there for me. Music is an essential part of my life, and I have eclectic tastes, but there has always been jazz music. At seventeen, I’m at a Rahsaan Roland Kirk concert in my hometown of Manchester, England, stunned by the transgressive beauty of this man’s performance. At fifty-seven, my wife has died, and I can’t bear to hear lyrics, so it’s Kind of Blue and Trane ballads. And today I’m listening to ‘Round Midnight, Monk alone at the piano, stunningly honest and almost unbearably intimate.

…..So as an artist I need to give something back, but make it my own, and make it new.

…..As a conceptual artist, my photo-narratives are hybrid forms, transgressing distinctions between the verbal and the visual: the image as text. My art represents a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis: the words, the images (abstract and referential), the space between images, the subjects, the reference to specific individuals, places, or times. As the artist Alexis Smith says of her collages and assemblages: “It’s fused into a whole where they seem like they’ve always been together, or were meant to be together. The people that look at them put them together in their heads.” Some visual references are obvious; some of the bones, sinews, and other connective tissue that hold a particular narrative together work within the piece’s own logic, a logic that viewers find for themselves. Here, the artist makes the work, and that work has an agenda, but a significant part of that agenda is for the viewer to find something of (or for) themselves within these images and words.

…..Each work in this series of “Jazz Narratives” is anchored by a person (a musician) and a related place. I am especially interested in the “aura” of these places. Sometimes, the place remains relatively unchanged seventy years after the musical fact; sometimes, only a physical street number remains, if that. What matters is that, for the artist and the viewer, this aura remains. This, say, is 151 Avenue B, on the Lower East Side; the brownstone is easy to miss if you are walking along the east side of Tomkins Square Park, but if you know that Charlie Parker lived there, it has become something more than the stone and glass of the place. 4201 S. Central Avenue, Los Angeles, is an anonymous mixed-use building, but there’s the number above the glass doors; 4201 S. Central is the Downbeat Club. Here, in 1945, Clora Bryant first heard bebop: here, on this corner, and that corner is still here, as is that night and all those other nights.

…..Some years ago in Brooklyn, I went looking for 99 Ryerson Street, where the poet Walt Whitman had lived when Leaves of Grass was first published. The fact that Whitman had lived here had only recently been discovered, and the 1850s wood-frame house was unmarked and unchanged except for aluminum siding and the addition of an extra floor. It is the only surviving Whitman residence in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Standing on the original bluestone sidewalk slabs, I was looking at Whitman, whose vision of America was a primary reason for my decision to emigrate to the United States. In my excitement, I crossed the street and spoke to an elderly man sitting on the stoop opposite. “Do you know that Walt Whitman lived in that house?” I asked, clearly appearing to be a madman. The neighbor looked up at the crazy person: “Is that the guy who is renting a room?” For him, the aura was not visible.

…..These pieces are works of homage; I am making some kind of unsentimental pilgrimage to each of these apparently anonymous street addresses. And I am conjuring ghosts; they are still alive in these places as they are in their recordings. The music may have been recorded in 1947, but they are playing it now. You can hear that. And, if I am successful, you can see the musicians in my art.

.

_____

.

.

.

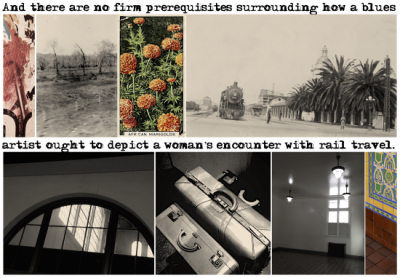

The Entrance of Bessie Smith into San Diego

(1050 Kettner Blvd., San Diego)

2020

.

…..

…..1050 Kettner Boulevard is the downtown location of San Diego’s Santa Fe Depot. Built in 1915 in the Spanish Colonial Revival style, the building is a secular cathedral. In Thomas Hardy’s 1895 novel Jude the Obscure, Jude Fawley and Sue Brideshead have the following exchange:

…..“Shall we go and sit in the cathedral?” he asked when their meal was finished.

…..“Cathedral? Yes. Though I think I’d rather sit in the railway station,” she answered. . . . “That’s the centre of the town life now. The cathedral has had its day!”

…..“How modern you are!”

…..In the late 1920s, Columbia bought Bessie Smith a custom-made personal railroad car, in part because of segregation. Painted bright yellow with green lettering on the sides, the car could accommodate Smith and the performers in her show.

…..The title of this piece was inspired by a favorite painting: James Ensor’s The Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889. Bessie Smith would be arriving in San Diego to perform at the Creole Palace.

…..The verbal text comes from Claudia May’s essay, “Railroad Blues: Crossing the Tracks of Gender, Class, and Race Inequities in the Blues and Ann Petry’s The Street.” (The essay appears in Trains, Literature, and Culture: Reading and Writing the Rails, edited by Steven D. Spalding and Benjamin Fraser.) Am I using the scholarly language ironically? Yes and no.

…..The Entrance of Bessie Smith into San Diego was inspired by Smith’s “Dixie Flyer Blues” from 1925.

…..The song’s vision of “Dixieland” is romanticized, but perhaps Smith is assuming a different persona in these lyrics:

…..On that choo-choo, mama gonna find a berth

…..Home into Dixieland.

…..It’s the grandest place on earth.

…..Dixie Flyer, come on and let your driver roam.

…..Wouldn’t stay up North to save nobody’s doggone soul.

…..Born in Chattanooga, Smith moved to Philadelphia in 1920, and her actual feelings about the South were mixed. At the age of 43, Bessie would die there, following a road accident north of Clarksdale, Mississippi. And it would be another train that carried her body back to Philadelphia.

…..It is perhaps worth remembering here that in 1903 W. C. Handy first heard the blues on a railway station platform in Tutwiler, sixteen miles south of Clarksdale. However, Claudia May notes that, “While numerous scholars associate a black male figure with the blues, the blues train metaphor need not be confined to this assumed masculine trope. As singers, composers, arrangers, and characters, women play an important role in shaping the formation of the blues.” Indeed.

…..The quotation from Jude the Obscure that appears above is to be found in the third section of the novel, which Hardy begins with an epigraph taken from Sappho: “For there was no other girl, O bridegroom, like her!” In so many ways, Sappho could be describing Bessie Smith.

…..Perhaps, in San Diego’s cathedral of Santa Fe, we can worship a woman who would both thrive on such adoration and laugh at the chumps who make up the faithful.

.

.

___

.

.

.

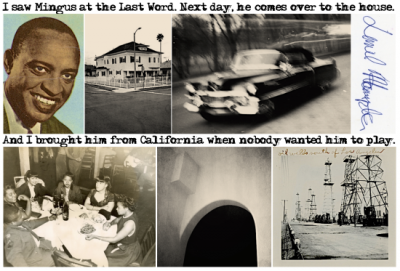

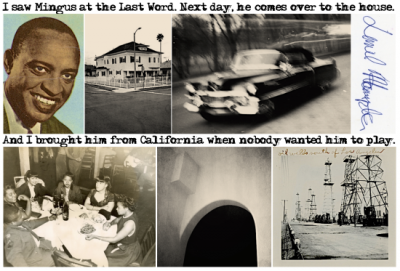

Lionel Hampton Is Coming to Dinner at Dr. Gordon’s House

(238 E. 45th St., Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..Continuous torrential rain marked the March day when I made my pilgrimage to Dexter Gordon’s childhood home. Streets in South Central were flooded. Looking carefully at the first image in this piece, the viewer may see drops of rain hitting the water in the gutter outside Number 238. The rain allowed for useful reflections of the white gate at the neighboring house and, for a day, changed the surface texture of the concrete.

…..Dexter Gordon’s father, Dr. Frank Gordon, was the first African-American physician in Los Angeles and included Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton among his patients. Growing up, Dexter would find musicians such as Ellington, Hampton, Ethel Waters, and Marshal Royal at his parents’ dinner table. Lionel Hampton’s home was fifteen minutes’ walk from 238 E. 45th Street.

…..Dr. Gordon gave his son a clarinet at thirteen, and Dexter took lessons from John Sturdevant, a clarinet player from New Orleans. Dexter talks of falling in love with the “big fat clarinet sound” of New Orleans musicians such as Barney Bigard, who would himself move to Los Angeles after fifteen years with Ellington’s orchestra.

…..On Los Angeles’s Eastside, Dexter’s first jobs were a paper route and mowing lawns. His best friend, Lamar Wright Jr., lived directly across from Lionel Hampton on the corner of Wadsworth and 43rd Street. The neighborhood – and it was very much a cohesive neighborhood – referred to Dexter and Lamar as “Mutt and Jeff,” Lamar being short and Dexter being six feet five inches by the age of fifteen. (The panel in this work is taken from a 1913 Mutt and Jeff comic strip.)

…..Fifteen years younger than Lionel Hampton, Dexter Gordon would play in the saxophone section of Hampton’s band between 1940 and 1943. The manipulated image of Hampton playing drums is a Swedish chewing-gum card.

…..The found photograph of a young man standing outside the Los Angeles house might depict Dexter Gordon.

…..“Now you’ll have to answer these questions as a matter of form,” the cop asks Mutt. “Are you colored or white?” “White, of course,” Mutt replies. It’s the right answer. It was the right answer in 1913; it was the right answer in 1923, the year of Dexter Gordon’s birth. Eastside, Watts, and Central Avenue were flourishing, cohesive communities (not forgetting that they were communities whose borders were marked by red lines), but the LAPD would always be looking for the right answer and would continue to be looking for the answer that they wanted to hear. In The Birth of Bebop: A Social and Musical History, Scott Devaux notes, “Not without reason did some musicians refer to Los Angeles as ‘Mississippi with Palm Trees.’” And Devaux quotes the writer Chester Himes:

…..Los Angeles hurt me racially as much as any city I have ever known – much more than any city I remember from the South. It was the lying hypocrisy that hurt me. Black people were treated much the same as they were in an industrial city of the South. They were Jim-Crowed in housing, in employment, in public accommodations, such as hotels and restaurants.

…..It never rains in Southern California.

…..It pours, man. It pours.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Lionel Hampton: Central Avenue Breakdown

(East 43rd St. and Wadsworth Avenue, Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..Lionel Hampton was a man of rich complexity. The drummer and pianist who, of course, introduced the vibraphone as a legitimate jazz instrument. The half-brother of Sammy Davis, Jr. The nephew of Richard Morgan, Bessie Smith’s true love and the man driving their car when Bessie Smith suffered fatal injuries (a tragedy from which Morgan, physically unharmed, would never recover). Brought up by his grandmother, an evangelical faith healer, Lionel attended Catholic schools, was fascinated by Judaism, and later in life became a Christian Scientist. Lionel Hampton would join Benny Goodman in the first integrated jazz band. He was a swing orchestra leader who brought a young Dizzy Gillespie into the band, a band with which Miles Davis would sometimes sit in. A dance-band leader who would incorporate bebop and rock and roll into his repertoire. Hamp was a lifelong Republican who campaigned for LBJ. He was a philanthropist who built public housing projects in Harlem and New Jersey.

…..In Lionel Hampton’s autobiography, he uses the somewhat oddly constructed sentence, “I brought Mingus from California when nobody wanted him to play.” Did he first see Mingus play at the Last Word on Central Avenue? Perhaps. Hampton’s home was a block away from Central Avenue, around the corner from the Dunbar Hotel. As I write this, we are in the middle of a pandemic, and I was unable to go to East 43rd and Wadsworth to photograph the house myself. Instead I have heavily manipulated a Street View image of the building (Art in the Time of Covid-19). The home is now divided up into apartments. The house across the street where Dexter Gordon’s best friend Lamar Wright lived has become a parking lot; however, the Phillips Temple CME Church still stands on the northwest corner.

…..When Mingus left the Lionel Hampton Orchestra in 1948, the bass player had trouble finding work, despite a period as leader at the Last Word. When Red Norvo picked him up for the Red Norvo Trio, the reluctant Mingus was hard to find, Norvo eventually discovering him working as a mailman in Watts.

…..In 1946 Richard Nixon, running for California’s 12th congressional district, approached Hampton and asked for his assistance in a Black voter registration drive (Hamp would go on to become an assistant campaign manager for Nixon). Hampton’s band played “up and down Central Avenue,” each performance including an appearance by Nixon. In his successful 1960 senate race, Nixon turned to Hampton again. In Hamp’s autobiography, he writes of Nixon, “He must have decided Central Avenue was lucky for him, because the night of the election he was sitting in a little bar there, called the Last Word, drinking beer.” Across the street from the Downbeat, the Last Word was central to the development of young bebop musicians on Central Avenue. Richard Milhous Nixon drinking beer there on the night of the 1960 election. Picture that. I can’t. (I have tried, and I have failed every time.)

…..Was the wartime photograph of the women at a jazz club taken in the Last Word? It should have been. For me, the strength of this image lies in its focus on the young woman returning the lens’s gaze.

…..The found photograph that closes the piece, “oil wells south of Los Angeles,” is intended to evoke a period landscape. But in the back of my mind, I can also hear Hamp reflecting in his autobiography on the year 1960, when his big band celebrated its twentieth anniversary: “[W]e were rich. We owned something like twenty-two houses in Los Angeles, property in Las Vegas, land in Texas where they’d struck oil, so we had oil royalties coming in. I didn’t like to talk about it in public – one word and those taxation hound dogs were after you – but we were rich.”

…..The manipulated portrait of Hampton is a Swedish chewing-gum card from the artist’s collection, as is the original autograph.

…..The title of this work comes from the instrumental “Central Avenue Breakdown.” Composed by Hampton, the piece was recorded in 1940, and featured the composer’s friend Nat “King” Cole on piano. An influential pianist, Nat Cole was always being encouraged by Hamp: “I was the one who kept telling him, ‘Man, you sing. You sing.’” Cole ended up acting upon that advice.

.

.

___

.

.

All pieces are archival inkjet prints, 4½ x 6½ inches, framed to 14 x 14 inches. For more information, visit charlesingham.com

.

.

To see Volume 1 of this series, click here

To see Volume 2 of this series, click here

To see Volume 3 of this series, click here

To see Volume 4 of this series, click here

To see Volume 5 of this series, click here

To see Volume 6 of this series, click here

To see Volume 7 of this series, click here

To see Volume 8 of this series, click here

To see Volume 9 of this series, click here

.

___

.

.

photo by Jacqueline Ramirez

.

Born and educated in England, Charles Ingham moved to California in 1982. He has always been interested in hybrid forms and the intersection of literature and the visual arts, his photography often seeking to transgress the traditional boundaries separating the verbal and the visual.

Ingham lives in San Diego and shows his work at Distinction Gallery in Escondido. He recently had three pieces accepted for the 28th Annual Juried Exhibition at the Athenaeum Music and Arts Library, La Jolla. He also had two pieces shown in the “Six-Word Story” exhibitions at Front Porch Gallery, Carlsbad, and the Oceanside Museum of Art.

His work can be found.at his website: charlesingham.com

.

.

.

.

.

.</span