.

.

.

“Watching the Sea” is one of several photo-narratives in Charles Ingham’s new series devoted to his love of jazz music, “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives”

These photo-narratives are provocative and meaningful– connecting time, place, and subject in a way that ultimately allows the viewer a unique way of experiencing jazz history.

To enhance the opportunity for appreciation of this artistic series, in the coming weeks “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives” will be featured on Jerry Jazz Musician three-at-a-time, and will include the artist’s description of each piece.

.

.

This edition’s narratives, found below the artist’s introduction, are:

.

“Torn from Its Moorings”

“Watching the Sea”

“Plantations”

.

.

_____

.

.

Charles Ingham introduces his “Jazz Narratives” series

.

…..Jazz has always been there for me. Music is an essential part of my life, and I have eclectic tastes, but there has always been jazz music. At seventeen, I’m at a Rahsaan Roland Kirk concert in my hometown of Manchester, England, stunned by the transgressive beauty of this man’s performance. At fifty-seven, my wife has died, and I can’t bear to hear lyrics, so it’s Kind of Blue and Trane ballads. And today I’m listening to ‘Round Midnight, Monk alone at the piano, stunningly honest and almost unbearably intimate.

…..So as an artist I need to give something back, but make it my own, and make it new.

…..As a conceptual artist, my photo-narratives are hybrid forms, transgressing distinctions between the verbal and the visual: the image as text. My art represents a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis: the words, the images (abstract and referential), the space between images, the subjects, the reference to specific individuals, places, or times. As the artist Alexis Smith says of her collages and assemblages: “It’s fused into a whole where they seem like they’ve always been together, or were meant to be together. The people that look at them put them together in their heads.” Some visual references are obvious; some of the bones, sinews, and other connective tissue that hold a particular narrative together work within the piece’s own logic, a logic that viewers find for themselves. Here, the artist makes the work, and that work has an agenda, but a significant part of that agenda is for the viewer to find something of (or for) themselves within these images and words.

…..Each work in this series of “Jazz Narratives” is anchored by a person (a musician) and a related place. I am especially interested in the “aura” of these places. Sometimes, the place remains relatively unchanged seventy years after the musical fact; sometimes, only a physical street number remains, if that. What matters is that, for the artist and the viewer, this aura remains. This, say, is 151 Avenue B, on the Lower East Side; the brownstone is easy to miss if you are walking along the east side of Tomkins Square Park, but if you know that Charlie Parker lived there, it has become something more than the stone and glass of the place. 4201 S. Central Avenue, Los Angeles, is an anonymous mixed-use building, but there’s the number above the glass doors; 4201 S. Central is the Downbeat Club. Here, in 1945, Clora Bryant first heard bebop: here, on this corner, and that corner is still here, as is that night and all those other nights.

…..Some years ago in Brooklyn, I went looking for 99 Ryerson Street, where the poet Walt Whitman had lived when Leaves of Grass was first published. The fact that Whitman had lived here had only recently been discovered, and the 1850s wood-frame house was unmarked and unchanged except for aluminum siding and the addition of an extra floor. It is the only surviving Whitman residence in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Standing on the original bluestone sidewalk slabs, I was looking at Whitman, whose vision of America was a primary reason for my decision to emigrate to the United States. In my excitement, I crossed the street and spoke to an elderly man sitting on the stoop opposite. “Do you know that Walt Whitman lived in that house?” I asked, clearly appearing to be a madman. The neighbor looked up at the crazy person: “Is that the guy who is renting a room?” For him, the aura was not visible.

…..These pieces are works of homage; I am making some kind of unsentimental pilgrimage to each of these apparently anonymous street addresses. And I am conjuring ghosts; they are still alive in these places as they are in their recordings. The music may have been recorded in 1947, but they are playing it now. You can hear that. And, if I am successful, you can see the musicians in my art.

.

_____

.

.

.

Torn from Its Moorings

(638 S. Kenmore Ave., Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..In the Haig, one could hardly find a more unlikely structure that would serve as a vital location in the development of jazz music (both West Coast and East Coast, if one sees the geographic development of modern jazz as being simply binary). Originally a residential bungalow, the house grew somewhat as it became a club. The building accommodated an audience of around eighty-five, its neon roof sign almost dwarfing the club that it advertised. The Haig sat precariously on the corner of South Kenmore and Wilshire, directly across the street from the luxuriously kitsch Cocoanut Grove nightclub, housed in the Ambassador Hotel. Of the Haig, trumpet player Shorty Rogers noted, “If you took four steps, you crossed the room.” For a time, a guardrail around the front of the tiny bandstand stopped Dave Brubeck from plunging into Ava Gardner’s martini and prevented Orson Welles from stepping on Gerry Mulligan’s toes. (Indeed, during the quartet’s eleven-month residency at the Haig in 1952, Mulligan was celebrated for his habit of stopping the band mid-flight and berating the audience for talking during his set.)

…..The club closed in 1956, and today the bungalow is gone, replaced by a high-rise commercial building. The first image in my work depicts an art-adapted dumpster outside the entrance to the new building’s parking garage. Below is a photograph of the Evanston Apartments, which once loomed over the Haig.

…..In late 1949, Ornette Coleman arrived in Southern California, where he worked for two years as an elevator operator in a branch of Bullock’s department store. In West Coast Jazz, Ted Gioia notes that Coleman, “newly arrived in town,” sat in at the Haig with the tenor saxophonist James Clay and “played a version of ‘Embraceable You’ which left the patrons unsettled with its vision of jazz to come.”

…..Finally, the saxophone depicted in this work appears to be made of brass. It is not a cream-colored acrylic plastic Grafton, nor is it a white-lacquered Selmer; however, Ornette Coleman did not play these two models exclusively. And this is a 1/6 scale plastic saxophone made in China. And is it an alto? Here, it is Ornette Coleman’s instrument.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Watching the Sea

(206 Market St., San Diego, California)

2020.

.

[Billie Holiday contact sheet, unknown photographer. Collection of the artist.]

.

…..Lady Day performing at the Creole Palace in downtown San Diego.

…..The verbal text conflates lyrics from two of Billie Holiday’s recordings: “Ain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do” and “I Cover the Waterfront.”

…..The Creole Palace, a 500-seat ballroom, was housed in the Douglas Hotel on Market at Second Avenue, just over 1,000 yards from the water’s edge. In a town that was once part of New Spain and then Mexico, the dominant graffito in the first image reads “AGUA.”

…..Often referred to as the “Cotton Club of the West,” the San Diego club was distinct in a vital respect: At the high-priced Cotton Club the audience was almost exclusively white (in Langston Hughes’s words, “a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites”); at the Douglas Hotel there was no segregation. Indeed, Thursdays became the biggest night of the week at the Creole Palace, as the hotel’s African-American housekeepers had the night off and could get in the club for free.

…..Owned by African Americans, the Douglas Hotel opened in 1924, with the club closing in 1956, the building razed in 1986. Today, the site is occupied by a bland mixed-use residential and commercial development.

…..In this work, there are gardenias.

.

.

___

.

.

.

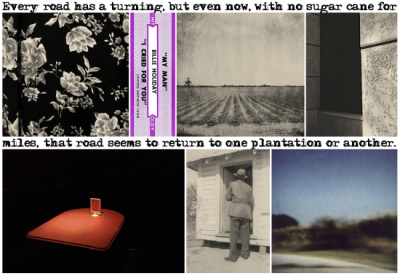

Plantations

(206 Market St., San Diego, California)

2020

.

…..Billie Holiday at the Creole Palace again.

…..“Every road has a turning”: a line from “I Cried for You.” (The jukebox label comes from the artist’s collection.)

…..The reference to plantations alludes to the opening sentence of Chapter 11 in Holiday’s autobiography: “You can be up to your boobies in white satin, with gardenias in your hair and no sugar cane for miles, but you can still be working on a plantation.” Holiday is referring to 52nd Street in the late thirties and early forties, but even at San Diego’s black-owned, unsegregated Creole Palace, the spirit of the plantation must still not seem far away.

…..And the found photograph of the man outside a cabin, a woman faintly visible in the darkened doorway, alludes again perhaps to the asymmetrical power structure of the plantation, this time in domestic relationships.

…..The photograph of the field was taken south of Clarksdale in the Mississippi Delta.

.

.

___

.

.

All pieces are archival inkjet prints, 4½ x 6½ inches, framed to 14 x 14 inches. For more information, visit charlesingham.com

.

.

To see Volume 1 of this series, click here

To see Volume 2 of this series, click here

To see Volume 3 of this series, click here

To see Volume 4 of this series, click here

To see Volume 5 of this series, click here

To see Volume 6 of this series, click here

To see Volume 7 of this series, click here

To see Volume 8 of this series, click here

To see Volume 9 of this series, click here

.

___

.

.

photo by Jacqueline Ramirez

.

Born and educated in England, Charles Ingham moved to California in 1982. He has always been interested in hybrid forms and the intersection of literature and the visual arts, his photography often seeking to transgress the traditional boundaries separating the verbal and the visual.

Ingham lives in San Diego and shows his work at Distinction Gallery in Escondido. He recently had three pieces accepted for the 28th Annual Juried Exhibition at the Athenaeum Music and Arts Library, La Jolla. He also had two pieces shown in the “Six-Word Story” exhibitions at Front Porch Gallery, Carlsbad, and the Oceanside Museum of Art.

His work can be found.at his website: charlesingham.com

.

.

.

.

.

.</span