.

.

.

“Communing with Ghosts” is one of several photo-narratives in Charles Ingham’s new series devoted to his love of jazz music, “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives”

These photo-narratives are provocative and meaningful– connecting time, place, and subject in a way that ultimately allows the viewer a unique way of experiencing jazz history.

To enhance the opportunity for appreciation of this artistic series, in the coming weeks “Charles Ingham’s Jazz Narratives” will be featured on Jerry Jazz Musician three-at-a-time, and will include the artist’s description of each piece.

.

.

This edition’s narratives, found below the artist’s introduction, are:

.

“The Artists Salute Each Other”

“Monk’s Mood at the It Club”

“Communing with Ghosts”

.

.

_____

.

.

Charles Ingham introduces his “Jazz Narratives” series

.

…..Jazz has always been there for me. Music is an essential part of my life, and I have eclectic tastes, but there has always been jazz music. At seventeen, I’m at a Rahsaan Roland Kirk concert in my hometown of Manchester, England, stunned by the transgressive beauty of this man’s performance. At fifty-seven, my wife has died, and I can’t bear to hear lyrics, so it’s Kind of Blue and Trane ballads. And today I’m listening to ‘Round Midnight, Monk alone at the piano, stunningly honest and almost unbearably intimate.

…..So as an artist I need to give something back, but make it my own, and make it new.

…..As a conceptual artist, my photo-narratives are hybrid forms, transgressing distinctions between the verbal and the visual: the image as text. My art represents a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis: the words, the images (abstract and referential), the space between images, the subjects, the reference to specific individuals, places, or times. As the artist Alexis Smith says of her collages and assemblages: “It’s fused into a whole where they seem like they’ve always been together, or were meant to be together. The people that look at them put them together in their heads.” Some visual references are obvious; some of the bones, sinews, and other connective tissue that hold a particular narrative together work within the piece’s own logic, a logic that viewers find for themselves. Here, the artist makes the work, and that work has an agenda, but a significant part of that agenda is for the viewer to find something of (or for) themselves within these images and words.

…..Each work in this series of “Jazz Narratives” is anchored by a person (a musician) and a related place. I am especially interested in the “aura” of these places. Sometimes, the place remains relatively unchanged seventy years after the musical fact; sometimes, only a physical street number remains, if that. What matters is that, for the artist and the viewer, this aura remains. This, say, is 151 Avenue B, on the Lower East Side; the brownstone is easy to miss if you are walking along the east side of Tomkins Square Park, but if you know that Charlie Parker lived there, it has become something more than the stone and glass of the place. 4201 S. Central Avenue, Los Angeles, is an anonymous mixed-use building, but there’s the number above the glass doors; 4201 S. Central is the Downbeat Club. Here, in 1945, Clora Bryant first heard bebop: here, on this corner, and that corner is still here, as is that night and all those other nights.

…..Some years ago in Brooklyn, I went looking for 99 Ryerson Street, where the poet Walt Whitman had lived when Leaves of Grass was first published. The fact that Whitman had lived here had only recently been discovered, and the 1850s wood-frame house was unmarked and unchanged except for aluminum siding and the addition of an extra floor. It is the only surviving Whitman residence in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Standing on the original bluestone sidewalk slabs, I was looking at Whitman, whose vision of America was a primary reason for my decision to emigrate to the United States. In my excitement, I crossed the street and spoke to an elderly man sitting on the stoop opposite. “Do you know that Walt Whitman lived in that house?” I asked, clearly appearing to be a madman. The neighbor looked up at the crazy person: “Is that the guy who is renting a room?” For him, the aura was not visible.

…..These pieces are works of homage; I am making some kind of unsentimental pilgrimage to each of these apparently anonymous street addresses. And I am conjuring ghosts; they are still alive in these places as they are in their recordings. The music may have been recorded in 1947, but they are playing it now. You can hear that. And, if I am successful, you can see the musicians in my art.

.

_____

.

.

.

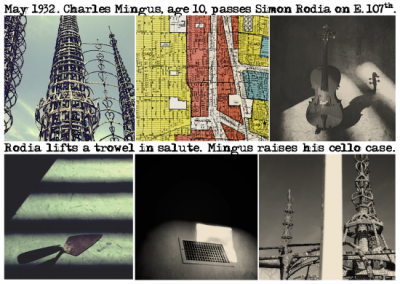

The Artists Salute Each Other

(1727 E. 107th Street, Watts)

2020

.

…..In Charles Mingus’s autobiography, the bass player refers to his childhood encounters with Simon Rodia as he walked from his home on East 108th Street to his elementary school on 103rd Street. As a child, Mingus played the trombone, then the cello, studying the double bass only in the late 1930s with Red Callendar, who notes that at the time the cello was still Mingus’s primary instrument. Charles Mingus lived just over a block away from Simon Rodia’s growing towers, and with friends used to gather “pretty rocks and broken bottles” to give to Mr. Rodia. Mingus and his friends would watch Rodia work: “Mr. Rodia was usually cheerful and friendly while he worked, and sometimes, drinking that good red wine from a bottle, he rattled off about Amerigo Vespucci, Julius Caesar, Buffalo Bill and all kinds of things he read about in the old encyclopedia he had in his house, but most of the time it sounded to Charles like he was speaking a foreign language” (Charles Mingus, Beneath the Underdog).

…..This work incorporates a section of the 1939 government-sponsored Home Owners Loan Corporation map of Los Angeles, focusing on the area encompassing the Watts Towers and Mingus’s home. According to the HOLC, communities with A ratings (color-coded green on the map) represented the best investments for homeowners and banks; B (blue), neighborhoods that were still desirable; C (yellow), those in decline; and D (red), areas considered hazardous. Hence the origin of the term “redlining.” Industrial areas (including that of the railroad tracks abutting the Towers) were left uncolored. Communities colored red tended to comprise ethnically heterogeneous areas, thus, in the racist logic of the banks and loan corporations, a cultural threat, a challenge to health and safety, and potentially subversive. This map institutionalized segregation in Los Angeles, its effects remaining with us today.

…..In this work, the “D” districts create their own red towers of bigotry, a perverted and distorted echo of Simon Rodia’s glorious architecture.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Monk’s Mood at the It Club

(4731 Washington Blvd., Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, all played the It Club, owned by John McClain. A friend of Bugsy Siegal, and often referred to as the “Black Godfather,” McClain was reputedly the biggest drug dealer in the city. Writing of the It Club in Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original, Robin Kelley notes that “McClain transformed this spacious room on West Washington Boulevard into the hippest spot in the city for modern jazz, momentarily shifting the center of gravity from the Sunset Strip to the ‘Westside’ black community. On the heels of the demise of Central Avenue – the heart of black Los Angeles’s jazz scene in the 40s and 50s – Washington between Crenshaw and LaBrea thrived. . . .Thelonious loved the It Club in part because he dug the neighborhood. . . . a neighboring beer and billiards joint, L.C.’s Hideaway, became his favorite refuge between sets.”

…..Recorded on October 31 and November 1, 1964, Monk’s Live at the It Club would be released posthumously as a double-LP almost two decades later.

…..Today the site of the It Club in Arlington Heights is occupied by a gray-stucco commercial building built in 1981. The architecture of the new building is austere and angular, but not without interesting details.

…..Fragments of Monk’s Mood (drawn from Steve Cardenas’s transcription) serve as an extra-verbal text in this piece. As I have noted before, all the works in my series of Jazz Narratives are comprised of fragments and represent a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis. Viewers who cannot read music may, I hope, be intrigued by the complex abstract beauty of the transcription and seek meaning within it; then they might turn to the narrative represented by the images to seek further significance. They might even work back and forth between the different elements of the piece to find some whole of their own making, a logic that is their own and parallel to the internal logic that is owned by the work itself. Viewers who can read music must accept my apologies for deconstructing anything created by Thelonious Sphere Monk.

.

.

___

.

.

Communing with Ghosts

(1608 N. Cahuenga Blvd., Los Angeles)

2020

.

…..One cannot over-emphasize the importance of the Hollywood jazz club Shelly’s Manne-Hole. Established in 1960, and co-owned by drummer Shelly Manne, the club created a jazz renaissance in Los Angeles. Everyone played at the Manne-Hole. Some jazz historians place the room on the ground floor, others insist that one descended stairs into a “nuclear bunker.” I like the idea of Roland Kirk breaking chairs during each set in that nuclear bunker, so in this piece I am going with the basement version of history.

…..A memory keeps nagging at me in this piece: My mother, a deeply religious and deeply superstitious person, insisted that passing someone on the stairs meant that you would never meet them in heaven. I am an atheist, but I am always uncomfortable if I have to pass anyone on a staircase, and, if I can, I avoid doing so. I’m not sure if this memory is relevant or not.

…..Writing on the fortieth anniversary of the Sunday at the Village Vanguard recordings, Adam Gopnik notes, “After Scott LaFaro’s death, Bill Evans became numb with grief; it took him months to recover, and there are people who think that he never did recover.” And Paul Motian, the trio’s drummer, remembers that for six months after the young bass player’s death, “Bill was like a ghost.”

…..“Brutally self-critical,” Evans, a Buddhist, may have seen a connection between his addictions and LaFaro’s death. From that time on, Evans would play “Porgy” almost obsessively, but almost always as a solo piece. Reflecting on the Vanguard recording, Paul Motian tells Adam Gopnick, “While we were listening to that number on the tape, Bill was a wreck, and he kept saying something like ‘Listen to Scott’s bass, it’s like an organ! It sounds so big, it’s not real, it’s like an organ, I’ll never hear that again.’” And Gopniak writes, “When we hear Evans play ‘Porgy,’ we are hearing what a good Zen man like Evans would have wanted us to hear, and that is the sound of one hand clapping after the other hand is gone.” Here on the stairs of Shelly’s Manne-Hole, we see one ghost communing with another, both lost.

…..In the upper right-hand corner of this work, alongside the utility box portrait, one may just be able to make out a worn stencil graffito on the sidewalk. In this photograph the text is inverted; it says, “Protect Yo Heart.”

…..Did Shelly Manne put a comforting hand on Bill Evans’s shoulder? The drummer was a man of both great talent and great warmth. He would have made that gesture.

…..Finally, I might note that the repeated appearance of the color blue in the piece is not an accident.

.

.

All pieces are archival inkjet prints, 4½ x 6½ inches, framed to 14 x 14 inches. For more information, visit charlesingham.com

.

.

To see Volume 1 of this series, click here

To see Volume 2 of this series, click here

To see Volume 3 of this series, click here

To see Volume 4 of this series, click here

To see Volume 5 of this series, click here

To see Volume 6 of this series, click here

To see Volume 7 of this series, click here

To see Volume 8 of this series, click here

To see Volume 9 of this series, click here

.

___

.

.

photo by Jacqueline Ramirez

.

Born and educated in England, Charles Ingham moved to California in 1982. He has always been interested in hybrid forms and the intersection of literature and the visual arts, his photography often seeking to transgress the traditional boundaries separating the verbal and the visual.

Ingham lives in San Diego and shows his work at Distinction Gallery in Escondido. He recently had three pieces accepted for the 28th Annual Juried Exhibition at the Athenaeum Music and Arts Library, La Jolla. He also had two pieces shown in the “Six-Word Story” exhibitions at Front Porch Gallery, Carlsbad, and the Oceanside Museum of Art.

His work can be found.at his website: charlesingham.com

.

.

.

.

.

.</span