.

.

“Catbelly Heat On My Knees,” a story by Ewing Eugene Baldwin, was a short-listed entry in our recently concluded 57th Short Fiction Contest. It is published with the permission of the author.

.

.

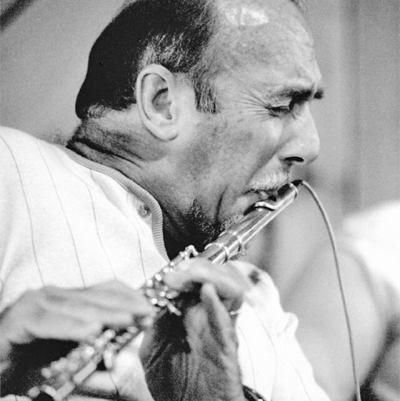

photo via hippopx/CC0 1.0 Universal

.

Catbelly Heat on My Knees

by Ewing Eugene Baldwin

.

___

.

The Bluesy Muse, Journal of Musicology

Autumn, 2020 Edition

.

“Catbelly Heat on My Knees”

By Joseph Wilson Miller, PhD

.

…..I’m retired—well, I was asked to retire because I wouldn’t teach online courses to remote classrooms of ingrate students looking at cat videos on their smartphones—but I keep my hand in the musicology profession, traveling around Illinois and collecting unpublished bits of Black music history. My doctoral thesis, Xylophones, Djembes, and Drums: Arthur Morris Jones and Homogeneity in Sub-Saharan African Music, was published in 1997. It sold fifty copies—well, forty-six copies. My colleagues and fellow Bluesy Muse contributors will understand.

…..The southwest part of the state has a connection with slavery and, oddly, the Confederacy. Some counties of Southern Illinois made a feeble attempt to secede from Illinois just prior to the Civil War. Over 5,000 slaves worked Illinois salt and lead mines in the 19th century. Escaped slaves headed for Canada, and freed slaves working as indentured servants, often met by accident: the runaway slave crossing a cornfield, the Black field worker weeding the corn watching him go.

…..A librarian in the state archive in Springfield told me she thought there was a famous bluesman in Macoupin County who had been an indentured farm worker descended from a slave. I drove south to Carlinville, the county seat of Macoupin County with its splendid old domed courthouse and limestone steps studded with Devonian fossils.

…..I located a file marked “Blind Bobbybaby Jax.” It told the story of an old Black man living in Macoupin County, an itinerant laborer, fruit picker and two-finger banjo plucker. His Yoruba mother Anjolaifeoluwa, slave name Mary, had escaped from her life along the Gulf Coast of Mississippi. His white father was unknown. Mary died in childbirth, leaving baby Bobby, who was born blind, to be raised by an unknown family. It is likely that young Bobby would have learned the music of the Delta, sorrow slave songs and field hollers.

…..John “Jack” Jax, a white evangelical minister and stove drummer, adopted young Baby Blind Bobby and the unlikely duo hit the road spreading the gospel and selling wood burning stoves to farmers. The blind boy, now called Blind Bobbybaby, would rub a washboard beat and sing, by way of entertaining potential stove buyers. Dubbed the “Two Jaxmen,” after Bobbybaby sang at a Baptist tent revival, they rode about in an old buckboard and worked the southern Illinois Territory, ending up one night in Jerseyville, where Jack Jax died of a stroke.

…..In 1883, the blues-influenced Jax wrote what is thought to be his first of thirty songs, Catbelly Heat on My Knees.

“I done scratched away my fleas/a little sour mash if you please/

Wouldn’t mind a woman to squeeze/I got catbelly heat on my knees.”

…..Blind Bobbybaby Jax was renowned for his ability to pick perfect apples despite his lack of sight. With orchard owner Jerry Wunderlich’s training, the boy would stand on a ladder against a tree, his hand touching apples as if they were targets, feeling for rot or odd shapes. Local white children would visit just to watch the apple picker. They would place dollar bills at the foot of the tree, so Jax tolerated them.

“Oh, dem chi’dren, how they bleat/they tiny hands clappin’ a beat/

Don’t feel like singin’—sheeet/Little white kids at my feet.”

…..Come the night, Jax would hold court outside the barn where he lived and slept. Poor white folks and the other two black residents of Macoupin County, Mr. Chas and Miss Gospelette, brother and sister servants in a mansion in Jerseyville, would gather to hear the signature “Mis’ssip” growl of Jax as the bluesman sang remembered songs from the Delta of his youth.

…..The referenced catbelly belonged to an enormous Maine Coon cat named Auntie Plato, a feline which adopted Jax and spent much of its life on the blues man’s lap. Auntie Plato was a legendary mouser and had birthed, by orchard owner Wunderlich’s estimate, over two hundred cat mutts with grotesque body shapes.

“Dang ol’ feline do as she please/Jealous pussy hissin’ at the breeze/

But I need her so much/that hot-hot catbelly heat on my old knees.”

…..Auntie Plato, Jax told anyone who would listen, had cured him of arthritis purely by the feline’s intense body heat. The cat spent much of its daytime hours straddling the shoulders of a bull, riding about the pasture and looking queen-like.

…..Rumor has it that the first blues man to ever be recorded, Charley Patton, on his way to Chicago from Memphis and hearing about Blind Bobbybaby Jax, stopped by the orchard and communed with Jax for part of a day. Patton was known for his guitar style, which would influence the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan, and his voracious appetite for women and booze. To quote Patton, Blind Bobbybaby Jax was “one motherfuckin’ plucker.”

…..We will never know if Blind Bobbybaby Jax might have been discovered that day, because Auntie Plato the cat attacked Patton, knocking him off a milking stool and ripping the musician’s hands to bloody shreds. (Robert Johnson posited in Dem da Blues Magazine that the Auntie Plato shredding might be responsible for Charley Patton’s frenetic fretwork). Curiosity didn’t kill the cat or Patton, but we do know that Patton drove away, and Jax wrote a dirge, Ol’ Cat Done Ripped My Heart.

“I loves my old cat/Ol’ Maine coon so smart/

I loves my old cat/No more spoonin’ in the dark/

You can take that old dang kitty/I think we got to part/

Because ol’ dang mangy thang/Maine cat done ripped my heart.”

…..A decade later, legendary musicologist John Lomax, on a tip from “father of country music” Jimmie Rodgers, who had heard Jax sing at the Illinois State Fair (they sang Rogers’ 1920s hit Blue Yodel #1 together), drove to the apple farm and asked to record Jax. Blind Bobbybaby Jax turned Lomax down flat. He was afraid, he told friends. Of what, he did not say. Perhaps he was worried that his entire repertoire of songs was about cats.

…..Blind Bobbybaby Jax died in 1935. Still picking apples, he reached for what he thought was a ripe fruit but was in fact a hornet’s nest, his hand stuck inside the nest and the hornets stinging the old man hundreds of times. Mr. Jax was buried next to the long dead Auntie Plato in a grove of oak trees. In his honor, a new varietal of sour red apple was named the Jax.

…..Bluesmen tell an anecdote about Charley Patton backstage at a concert in Atlanta, who, upon hearing of the death of Jax, supposedly said. “Goddam coon.” Presumably, he meant the cat.

…..If you’re driving east on Route 16, just a mile past the hamlet of Piasa, you will see a historic plaque along the shoulder of the highway:

…..“In memory of Blind Bobbybaby Jax, Blues Man, Apple Picker. ‘I got catbelly heat on my knees.’”

…..There are seven photos of Jax hanging in the Macoupin County Courthouse. In one, Jimmie Rodgers and Blind Bobbybaby pose with apples stuffed in their mouths. The white girl cheerleading team at Carlinville High School, their demure knee-length outfits modest by today’s standards, surround Jax and encircle him with pompoms. In another photo, Jax sits in an apple tree with Old Plucky, his banjo. The strangest photo depicts Jax with a group of smiling, suited white men one of whom holds a noose above Jax’s head. In yet another, Auntie Plato the Maine Coon cat is draped around Jax’s shoulders like a fur stole. Two Illinois State Fair photos show mobs of people standing in front of a stage, Blind Bobbybaby Jax playing banjo and an unknown Black man on washboard, his cheek stuffed with tobacco.

.

.

Joseph Wilson Miller is Professor Emeritus of Photosynthetic Polyglot, the James and Jane Horowitz School of All Things Considered Africa, at the University of Chicago. Dr. Miller’s new book, One Motherfucker Plucker: Blind Bobbybaby Jax and the Illinois Two-Finger, will be published by Piney Press next May. Xylophones, Djembes, and Drums: Arthur Morris Jones and Homogeneity in Sub-Saharan African Music, was hailed by Zambia News as “refreshing bling in the treasure that is the African music world.” Jazz Magazine Midwest called Miller’s book a “must-read for lovers of Sub-Saharan music.” “It’s a wow-wow-wow.” Xylophone-ies Newsletter

.

.

___

.

.

Ewing Eugene Baldwin is a freelance journalist, essayist (The Genehouse Chronicles), musician and playwright. Baldwin’s play, Water Brought Us and Water’s Gonna Take Us Away, about the Underground Railroad in Illinois, was commissioned by the National Park Service. The Yale University Climate Change Project recently featured his essay “The Five Seasons,” on the effects of warming in the Mississippi Valley. For the Alton Telegraph, Baldwin has published a series of articles on local Black history. His poem “Pas De Deux” was recently published by Tiny Seed Literary Journal. His essays and interviews with Tuskegee Airmen are in the national archives.

Visit his website at www.eugenebaldwin.com

.

.

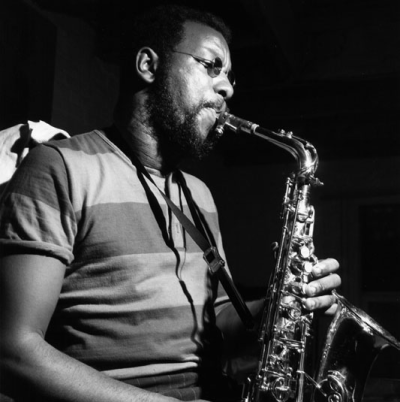

Listen to a 1964 recording of Reverend Gary Davis — a blues and gospel singer who also played the guitar, harmonica and banjo — playing “Candy Man.” The album was produced by legendary blues producer Samuel Charters, and was originally released on the Prestige Folklore label

.

.

___

.

.

Click here for details on how to enter your story in the upcoming Short Fiction Contest

Click here to read the winning story in the 57th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest, “Constant At The 3 Deuces,” Joe Zelazny

.

.

.

Highly entertaining story!

I love the humor, the satirical swipe at academic musicology. The wonderful characters and poetic almost musical flow of the short story was great. Jazz fiction at it’s best.

Baldwin’s humor and play with the sounds of words add another dimension to this essay about the blind black musician.